The School Sector Development Plan (SSDP) for Nepal (2016-2023) aims to ensure equitable access to quality education in line with the country's constitutional reforms and international commitments, particularly the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) regarding education. This plan builds on previous initiatives and addresses challenges such as the educational impact of the 2015 earthquakes, focusing on reconstruction and improved services for marginalized communities. The SSDP involves an inclusive, participatory approach to streamline educational reforms and development strategies necessary for transitioning to a federal governance structure.

![School Sector Development Plan (2016)

[MoE (2016). School Sector Development Plan, Nepal, 2016–2023.

Kathmandu: Ministry of Education, Government of Nepal.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ssdpfinaldraft-april42016-160719070015/85/Ssdp-final-draft-april-4-2016-2-320.jpg)

![School Sector Development Plan (2016)

CONTENTS

School Sector Development Plan...............................................................................................1

Nepal.........................................................................................................................................1

FY 2016/17–2022/23.................................................................................................................1

(BS 2073—2080)........................................................................................................................1

Ministry of Education................................................................................................................1

Government of Nepal................................................................................................................1

March 2016...............................................................................................................................1

[MoE (2016). School Sector Development Plan, Nepal, 2016–2023. Kathmandu: Ministry of

Education, Government of Nepal.].............................................................................................ii

Executive Summary....................................................................................................................i

Executive Summary....................................................................................................................i

Acknowledgments and Foreword..............................................................................................ii

Acknowledgments and Foreword..............................................................................................ii

Contents...................................................................................................................................iii

Contents...................................................................................................................................iii

Abbreviations and Acronyms..................................................................................................viii

Abbreviations and Acronyms..................................................................................................viii

1 Background and Context.........................................................................................................1

1.1 Background....................................................................................................................1

1.2 Country Context............................................................................................................2

1.3 Key Issues and Challenges.............................................................................................6

1.4 Main achievements of the SSRP..................................................................................11

1.5 Decentralized Planning ...............................................................................................12

1.6 Opportunities..............................................................................................................13

2 Overall Vision, Objectives, Policy Directions and Strategies...................................................15

2.1 Vision 2022..................................................................................................................15

iii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ssdpfinaldraft-april42016-160719070015/85/Ssdp-final-draft-april-4-2016-5-320.jpg)

![1 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

1.1 Background

Nepal is at a crossroads both at the global level with the beginning of the post-2015 Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs) era and at the national level with the rollout of the federal system

under the recently promulgated constitution (GoN 2015a). The School Sector Reform Plan (SSRP)

(MoE 2009) is the current Education Sector Plan, which was initiated in 2009 and ends in July

2016. As the follow-on of the Education Sector Plan, the government has developed this School

Sector Development Plan (SSDP) for the seven year period [mid-July 2016 to mid-July 2023(BS

2073–2080)] in line with Nepal’s vision to graduate from the status of a least developed country

(LDC) (NPC 2015a). The SSDP continues the government’s efforts to ensure access to quality

education for all through programmes such as Education for All (EFA; 2004-2007), the Secondary

Education Support Programme (SESP; 2003-2008), the Community School Support Programme

(CSSP; 2003-2008), the Teacher Education Project (TEP; 2002-2007) and most recently, the SSRP

(2009-2016).

Building upon the lessons learned and the gains made in the sector under these programmes,

the SSDP is designed to enable the school education sector to achieve unfinished agenda items

and to accomplish the targets defined under SDG number 4:

“Ensuring equitable and inclusive quality education and promoting life-long learning

opportunities for all’.

As such, the SSDP aligns with the commitment expressed by Nepal to the Incheon Declaration of

the World Education Forum and its Universal Declaration on Education by 2030 agenda (UNESCO

2015):

“to transform lives through education, recognizing the important role of education as

a main driver of development and in achieving the other proposed SDGs [….through] a

renewed education agenda that is holistic, ambitious and aspirational, leaving no one

behind.”

The SSDP also aligns with Nepal’s international commitment towards the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs), which were ratified by the UN General Assembly in September 2015.

In the case of Nepal, the development of the SSDP is aligned with the broader framework of

developing a national plan that encompasses the entire education sector and leads up to 2030,

similar to the Nepal National Plan of Action (NNPA) that was developed for the EFA

implementation timeline (2000-2015).

The SSDP was developed through an inclusive and participatory approach and is based on an

analysis of the education sector. Starting in June 2015,Thematic Working Groups (TWGs) were

formed, background papers developed, and knowledge gaps filled by carrying out thematic

studies. Consultations were undertaken with stakeholders at all levels to confirm and validate

strategic priorities. These processes led to the development of the SSDP Approach Paper (MoE

2015a), which outlined the broad policy directions and way forward and provided the basis for

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ssdpfinaldraft-april42016-160719070015/85/Ssdp-final-draft-april-4-2016-13-320.jpg)

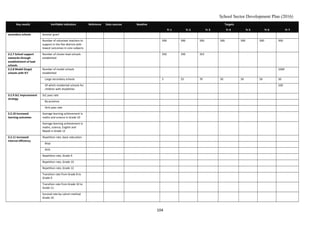

![School Sector Development Plan (2016)

1.1 Implementing the new constitutional mandate of federal arrangement and other policy reforms.

1.2 The integration of secondary and higher secondary levels and a system focus on secondary level

(9-12).

1.3 Develop the Governance and Accountability Framework.

1.4 Establish NEB, make administrative changes in existing examining bodies (Office of Controller of

Examinations [OCE], and the Higher Secondary Education Board [HSEB]) and select technically

strong staff for these organisations.

1.5 Reduced disparities between districts areas, such as the central Terai with low education

outcomes in terms of access, participation and learning outcomes.

1.6 Create units or divisions in national level organizations focused on secondary level education.

1.7 Structural reform to create one academic body for school education and rationalize staff.

1.8 ETCs, LRCs and recourse centres and persons function under guidance and control of National

Centre for Educational Development-Curriculum Development Centre (NCED-CDC)

1.9 Create a special project under SSDP to strengthen administrative measures, institutional

arrangements, teacher management and development and school improvement along with

social mobilization (with involvement of civil society organizations and traditional community

organizations) for education in these areas. This should be headed by a minister and a special

task force.

2. Strengthen financial management

2.1 Establish internal control and oversight capacity within MoE and DoE for supervising DEOs to

strengthen compliance with financial regulations.

2.2 Recruit/appoint chief finance and administrative officers within DOEs with qualifications relevant

for the positions.

2.3 DoE monitoring of school level accounting and financial reporting based on introduction of

simplified reporting and monitoring procedures.

2.4 DoE supervision/inspection of school level financial management including teacher payrolls and

grant utilization.

2.5 Roll out the Financial Comptroller General Office’s (FCGO) Computerized Government

Accounting System (CGAS) to all DEOs to serve as a web based integrated financial management

with data stored in central server accessible by the chief financial officers CFO of MoE, the

Ministry of Finance and FCGO for monitoring performance in budget execution

2.6 Improved compliance with financial regulations evidenced by reduced number of Office of the

Auditor General (OAG) recurring observations related to overspending of budget heads including

teacher salaries.

2.7 Improved predictability of budget execution by actual expenditure contained within approved

budget and total expenditure is no less than 95% of initially approved budget.

3. Strengthened management and accountability at school level

3.1 Full-time head teachers lead school improvements in large and lead secondary schools with

authority and accountability.

3.2 Define responsibilities and authority for school management by head teachers vis-à-vis SMCs.

3.3 Work out arrangements for school performance appraisals and head teacher accountability

3.4 Training and development of guidelines on financial management at the school level.

64](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ssdpfinaldraft-april42016-160719070015/85/Ssdp-final-draft-april-4-2016-76-320.jpg)

![School Sector Development Plan (2016)

7.3 Capacity Development

Objective

• To improve the quality and efficiency of service delivery through the establishment of a

capable and result-oriented workforce in the public education sector.

Background

To achieve this objective a costed institutional capacity development plan needs to be

developed that addresses the human resource and institutional capacity development needs of

civil servants and duty bearers in existing posts related to their current expected additional roles

and responsibilities under a restructured education sector, and for those recruited or transferred

in new positions created under SSDP. At the same time, the unfinished agenda in terms of

developing the capacity of regular functions and tasks of the system and the people working in it

need to be incorporated. The development of a plan for the strengthening of human resource

and institutional capacity is an integral part of the planning and implementation of the SSDP.

This plan will have three major dimensions:

• enabling the provision of education through the federal structure with decentralized

education management;

• strengthening decentralized education management with regard to educational planning,

management and budgeting; and

• ensuring capability-based recruitment and management of staff to ensure capacity

development results in competent and motivated staff. This “demands a series of

interventions [….], such as clear post descriptions for the various officials working at the

provincial and district levels; transparent and appropriate recruitment or nomination criteria

and procedures” (World Bank 2013).

As the full-fledged implementation of the federal structure is expected to be initiated soon

within the SSDP period (1-3 years) with institutionalization in the medium term (3-5 years), the

first years of SSDP implementation need to be used to prepare the system for this

transformation, both in management and funding structures as well as in human and

institutional capacities. As such, the plan should maintain flexibility and should be adaptable

based on consultation and discussions among policy-makers and technical staff within the

Ministry of Education, the Department of Education and other central level agencies on how the

federal structure is likely to impact the educational administration, and what implications this

has on the skill sets and competencies required by duty bearers. Furthermore, the skills

developed at provincial, district and local level to implement the past and on-going efforts to

decentralize the education system need to be revisited to ensure that they are relevant for

education planning, management and budgeting under the federal structure.

Learning from efforts undertaken in the past, the capacity development modality needs to be

revisited. Traditionally, capacity development was perceived as a synonym for training; however,

this perception is insufficient as training often does not result in strengthened institutional

capacity or in the improved quality of teaching and learning processes. The strategies to

strengthen skills sets and competencies and institutional performance need to take a more

holistic and results-based approach.

65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ssdpfinaldraft-april42016-160719070015/85/Ssdp-final-draft-april-4-2016-77-320.jpg)