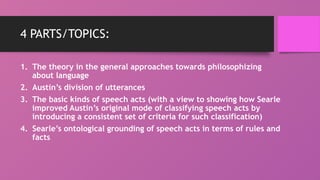

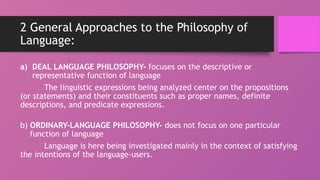

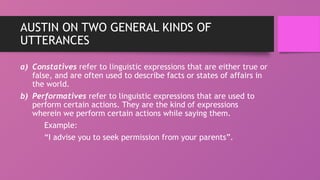

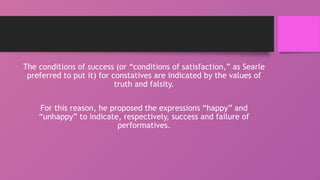

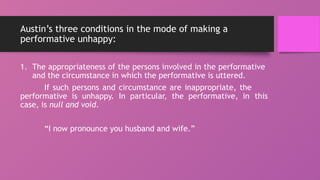

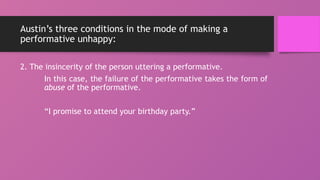

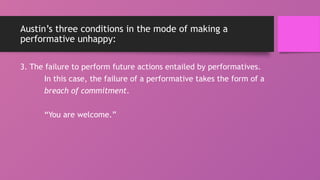

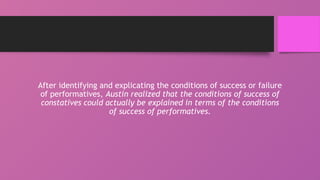

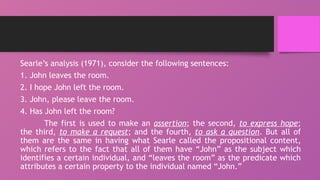

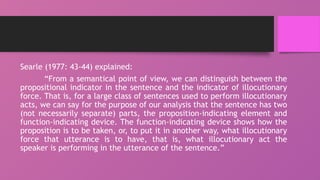

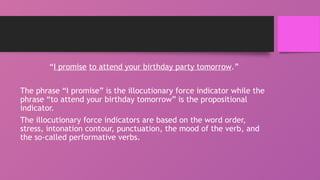

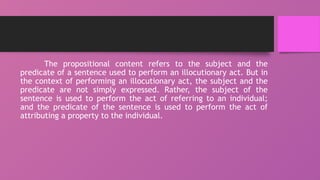

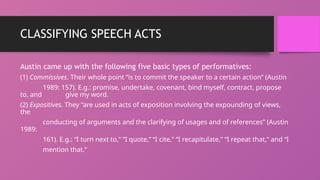

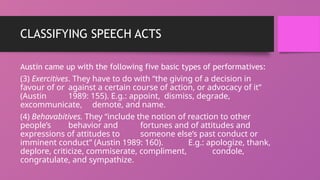

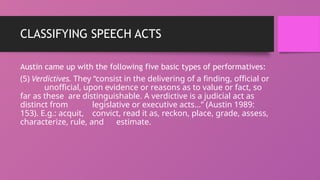

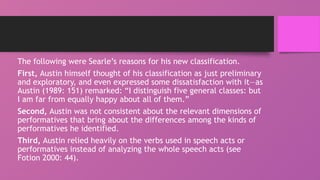

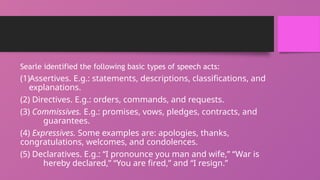

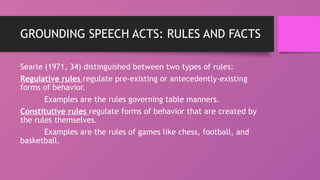

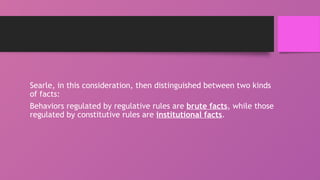

The document discusses speech act theory, focusing on the contributions of philosophers Austin and Searle in classifying and analyzing the functions of language. It outlines Austin's distinction between constatives and performatives, and Searle's expanded classification of speech acts into five basic types, emphasizing their linguistic and philosophical implications. The document also explores the grounding of speech acts in rules and facts, distinguishing between regulative and constitutive rules.