This case report describes a 26-year-old woman who experienced a spasm of the near reflex (accommodation, convergence, and miosis) when either eye was occluded or subjected to dioptric or non-dioptric blur. Her visual acuity decreased dramatically and an esodeviation was observed when either eye was occluded. Various occluders and lenses were able to trigger the spasm when a specific threshold of visual disruption was reached for each stimulus. Cycloplegia did not eliminate the spasm. This appears to be a rare case of a functional spasm of the near reflex triggered by binocular vision disruption, suggesting a potential anomaly in the neurological pathways involved in the

![triggered the spasm of the near reflex. This test was repeated several

times, and the same result was obtained each time.

Neutral-Density Filter Bar and Bagolini Red Filter

Bar (Sbisa Bar)

A neutral-density filter bar from 0.3 to 1.8 log unit optical

density values was placed in front of one eye over the glasses. The

spasm of the near reflex was induced when filter 0.9 (5.40 log of

luminance12

) and all darker filters were placed in front of the eye.

Filter number 10 (5.00 log of luminance12

) of the Bagolini red

filter bar induced the characteristic spasm, but not the lighter ones.

A normal sensory fusion response was reported with filter 9 (5.08

log of luminance12

), whereas filter 10 induced marked uncrossed

diplopia. Those neutral-density and red filters reduce the overall

luminance with only minimal visual acuity reduction (20/20 [6/6]

to 20/25 [6/7.5]).

For all the tested conditions, a spasm of the near reflex was

triggered whenever the left or the right eye was occluded. The

spasm was always immediately reversed when any of the occluders

inducing the spasm was removed. Cycloplegia (1 drop of cyclopen-

tolate HCl 1%) did not abolish this particular reaction to occlu-

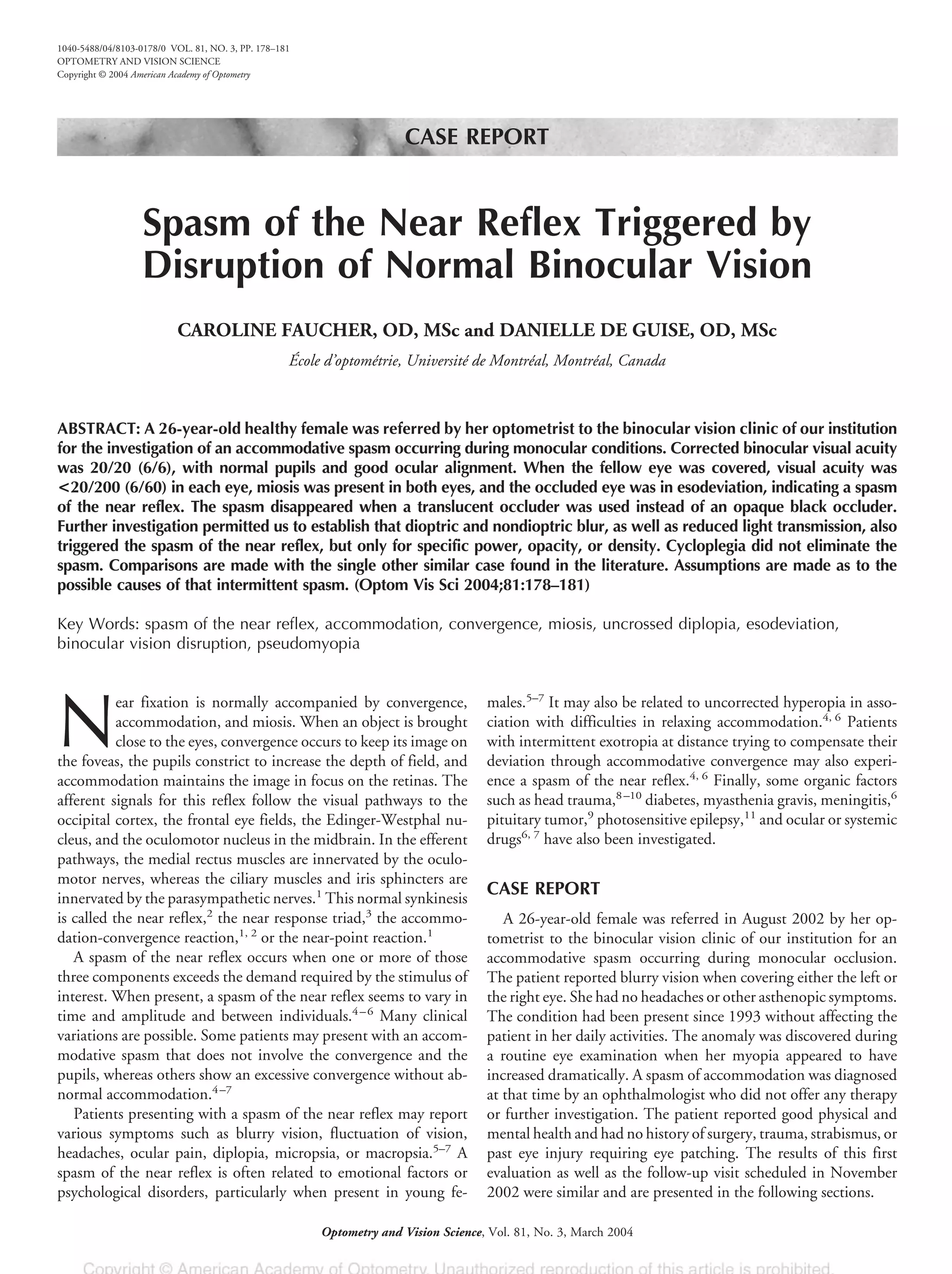

sion. Fig. 3 shows the patient with ϩ3.00 D (Fig. 3 A and C) and

ϩ3.50 D (Fig. 3 B and D) trial lenses, before cycloplegia (Fig. 3 A

and B) and during cycloplegia (Fig. 3 C and D). Note the bilateral

miosis (Fig. 3B) and esodeviation of the “covered” eye with ϩ3.50

D (Fig. 3 B and D) but not with ϩ3.00 D (Fig. 3 A and C), even

though the ϩ3.00 D lens decreases the visual acuity to about

20/200 (6/60). The cycloplegic refraction gave results similar to

the patient’s current ophthalmic correction.

Dilated slit lamp and fundus examinations were normal in both

eyes. A neurological evaluation was not recommended because the

condition was already present 10 years ago, the patient was asymp-

tomatic, and the spasm was only triggered by specific viewing

conditions.

DISCUSSION

We reported the special case of a 26-year-old woman presenting

with an occlusion-induced spasm of the near reflex. To our knowl-

edge, only one similar case has been reported in the literature.

Rutstein and Marsh-Tootle4

presented the results from the clinical

evaluation of a 27-year-old female with an accommodative spasm

induced by the occlusion of her right eye only. Their clinical find-

ings, however, differ from ours in several ways. The spasm they

reported was not accompanied by an esodeviation, and the pupils

appeared to constrict only minimally. In their report, the dioptric

blur created by a ϩ5.00 D lens did not induce the spasm of the

near reflex. They did not investigate other forms of occlusion to

elicit the spasm reported. Furthermore, cycloplegia abolished the

accommodative spasm found in their patient, whereas in the

present case, marked convergence occurred even during cyclople-

gia. The differences observed between the two cases reported may

be explained by the fact that the one reported by Rutstein and

Marsh-Tootle showed only an accommodative spasm without any

associated excess of convergence. The authors speculated that the

phenomenon could be similar to latent nystagmus in that it occurs

only when one eye is covered. They mentioned that this could also be

related to the work of their patient as a photographer, suggesting a

possiblelinkwithinstrumentmyopia.Thislatterexplanationmaynot

be applicable to our patient because she does not need to close either

eyeforherworkorhobbiesandsheneverusesamicroscope,telescope,

or any other device requiring monocular vision.

This unusual case of binocular spasm of the near reflex during

monocular occlusion without any associated history of ocular or

systemic disease or trauma is difficult to explain. The various stim-

uli used in our evaluation to disrupt the binocular vision through

different degrees and mechanisms were able to induce a spasm of

the near reflex: total occlusion, dioptric and nondioptric blur with

visual acuity disturbance, and luminance attenuation without sig-

nificant visual acuity reduction. It is interesting to note that it was

possible to determine a threshold at which each of those conflicting

stimuli disturbed the binocular vision, even though these thresh-

olds could vary between visits. The spasm was triggered whenever

the left or the right eye received a threshold signal of sufficient

attenuation. When both eyes were opened and nothing interfered

with binocular vision, the eyes remained straight, the pupils were

normal, and the patient had no symptoms. This led us to conclude

FIGURE 3.

Dioptric blur with a ϩ3.00 D lens (A) does not induce the spasm, whereas

(B) it does with a ϩ3.50 D lens. The spasm is also triggered during

cycloplegia (D) with the ϩ3.50 D lens but (C) not with the ϩ3.00 D lens.

180 Spasm of the Near Reflex—Faucher & de Guise

Optometry and Vision Science, Vol. 81, No. 3, March 2004](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/spasmofthenearreflextriggeredbydisruption-140614181032-phpapp02/75/Spasm-of-the_near_reflex_triggered_by_disruption-9-3-2048.jpg)