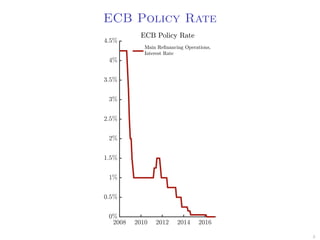

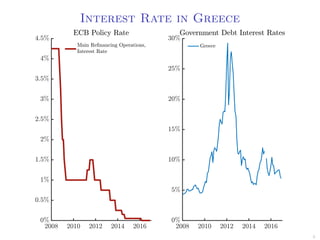

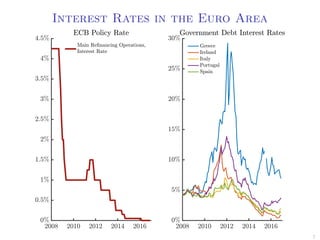

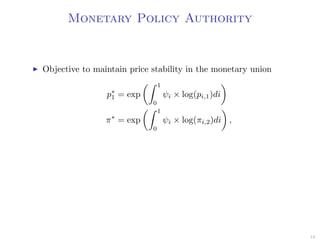

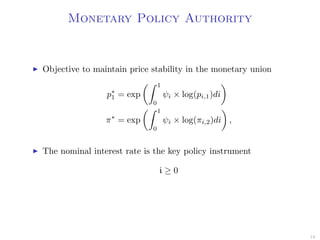

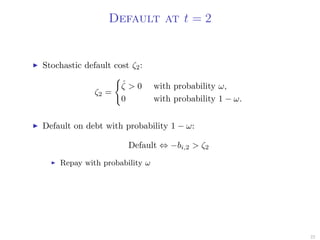

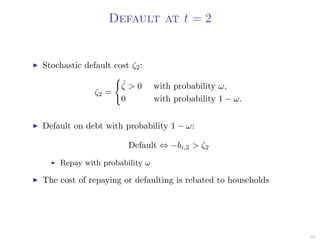

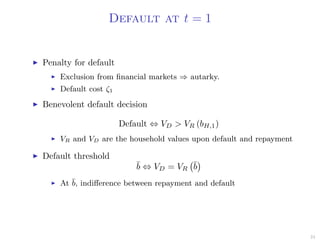

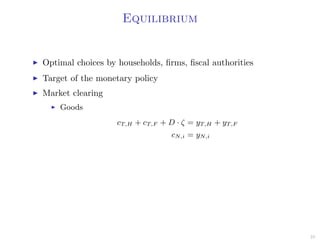

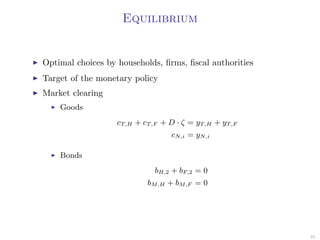

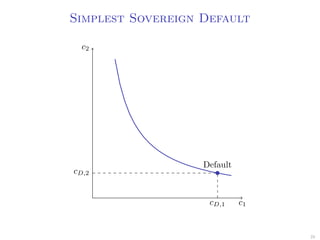

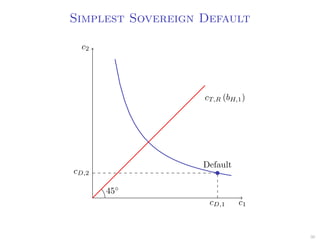

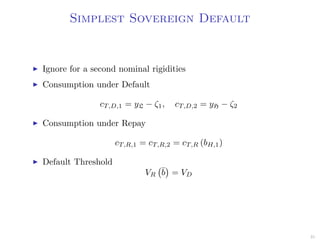

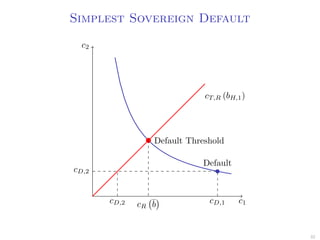

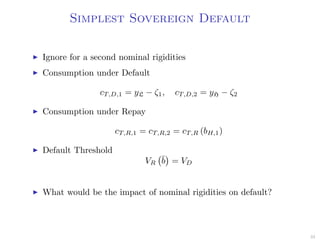

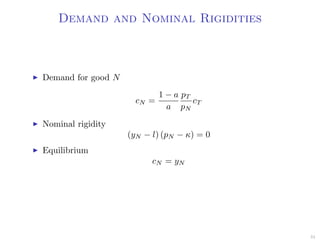

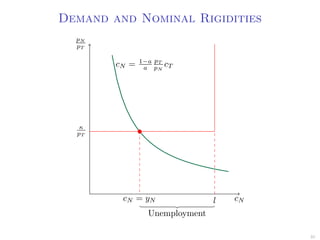

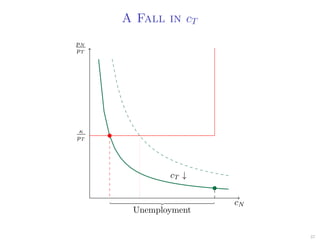

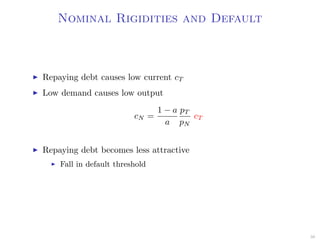

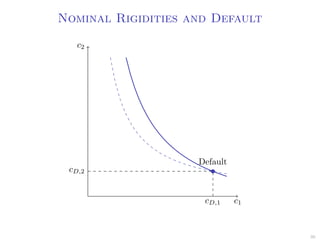

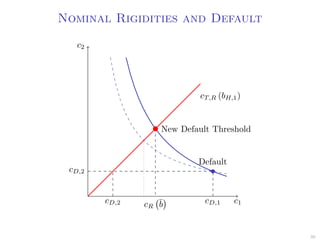

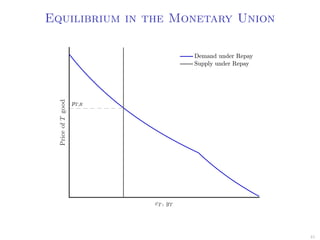

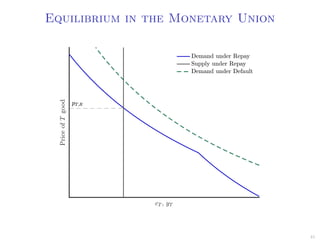

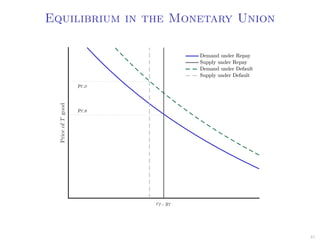

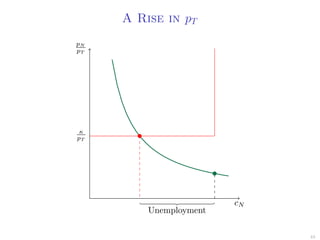

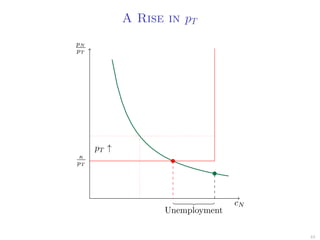

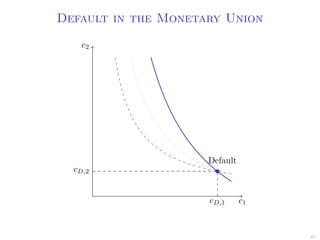

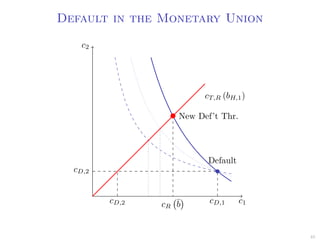

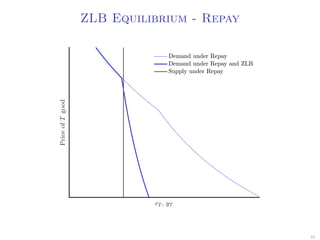

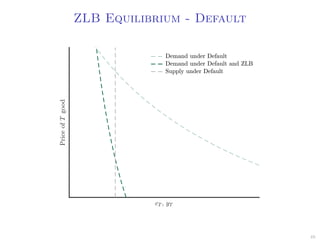

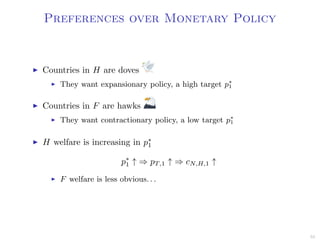

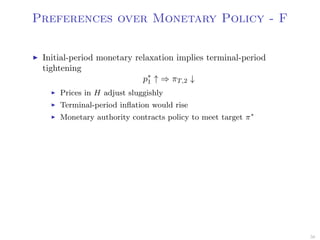

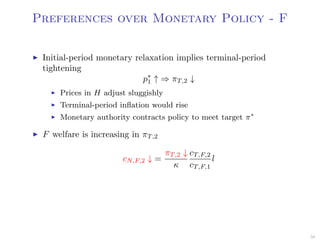

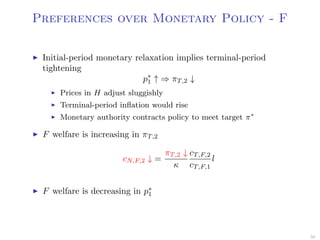

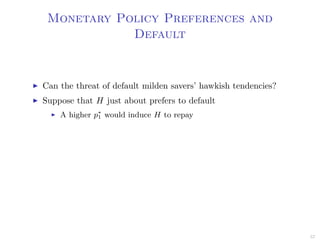

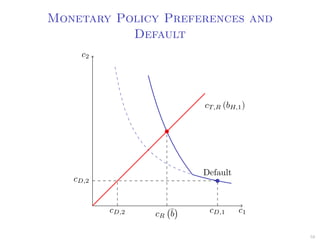

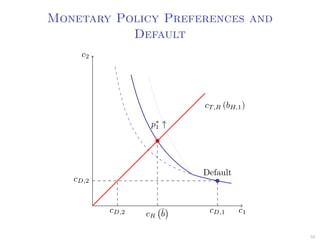

The document discusses sovereign default in a monetary union. It presents three motivating facts: (1) key interest rates falling to zero, (2) rising sovereign default risk and government borrowing costs, and (3) simultaneous increases in interest rates across euro area countries. The research questions examine how monetary policy and sovereign default influence each other. Key results show strong spillover effects between monetary policy and default. Default induces expansionary monetary policy and more default occurs in a monetary union. The zero lower bound prevents expansionary monetary policy and default causes large declines in demand.