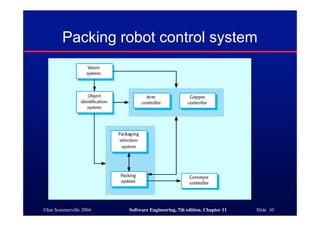

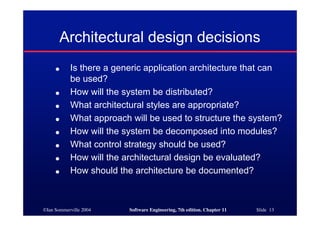

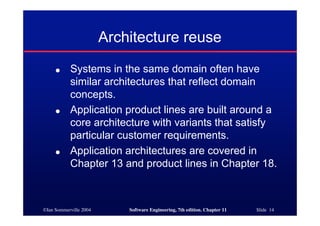

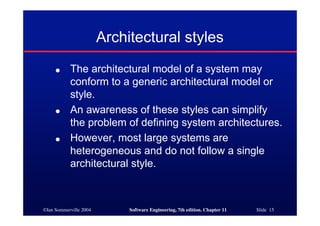

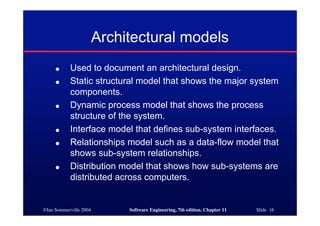

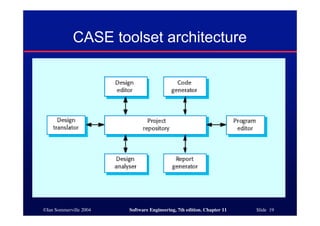

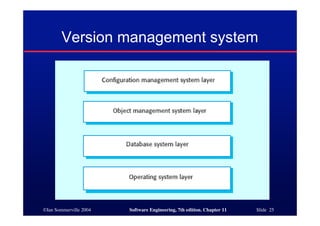

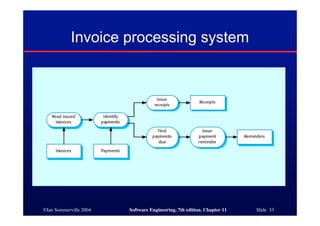

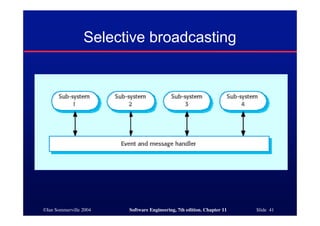

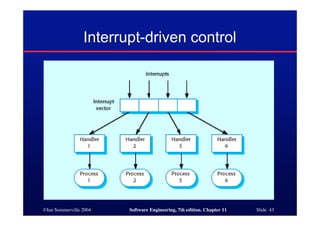

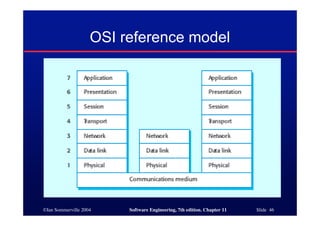

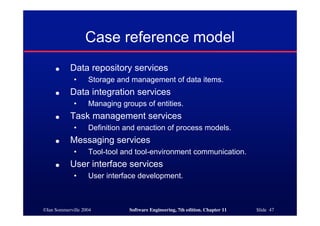

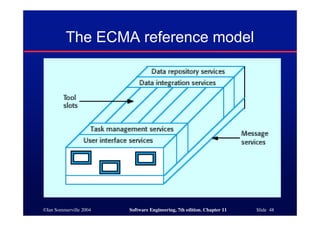

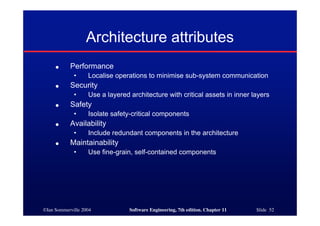

This document discusses architectural design and software architecture. It covers topics like architectural design decisions, system organization styles, decomposition styles, control styles, and reference architectures. The objectives are to introduce architectural design, explain important decisions, and discuss styles for organizing, decomposing, and controlling systems. Examples and characteristics of different architectural patterns are provided.