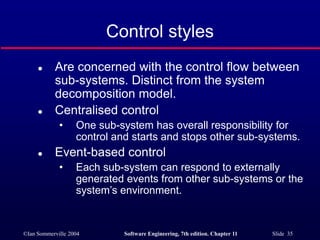

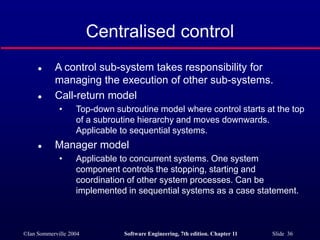

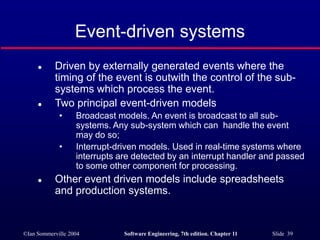

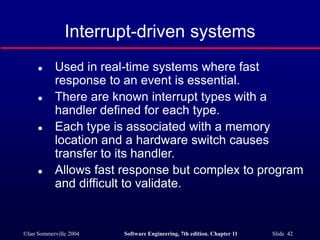

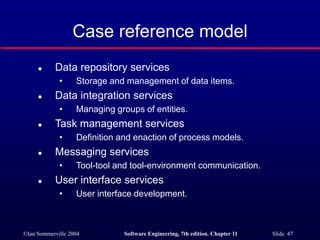

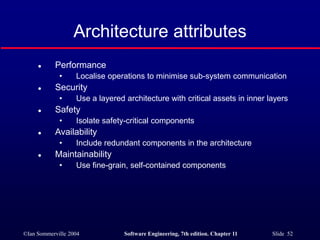

Chapter 11 of Ian Sommerville's 'Software Engineering' discusses architectural design, emphasizing its critical role in defining system structures and interactions. The chapter covers architectural design decisions, organizational models, modular decomposition styles, and the use of reference architectures for comparison and communication. Key considerations include performance, security, safety, availability, and maintainability of software architectures.