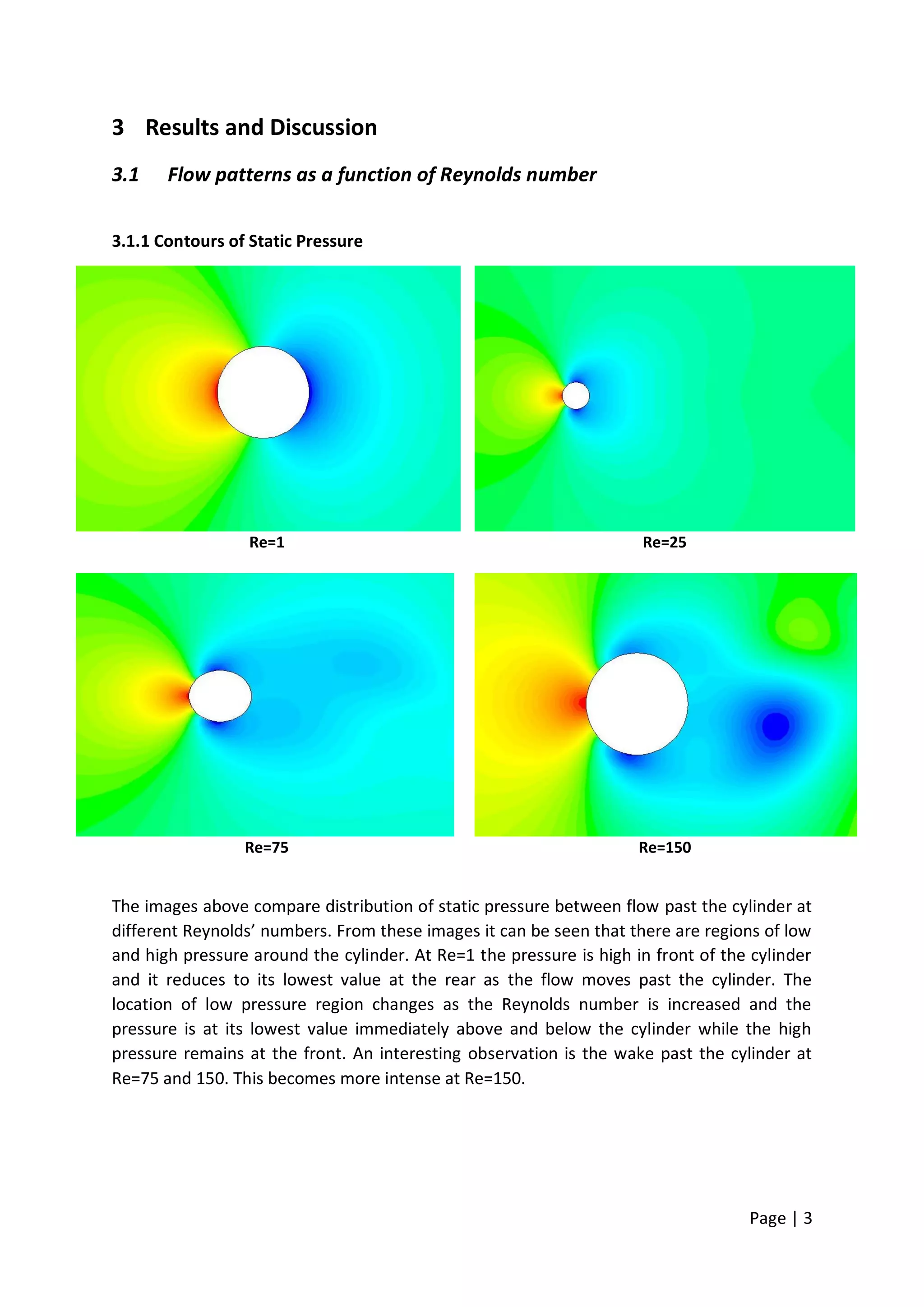

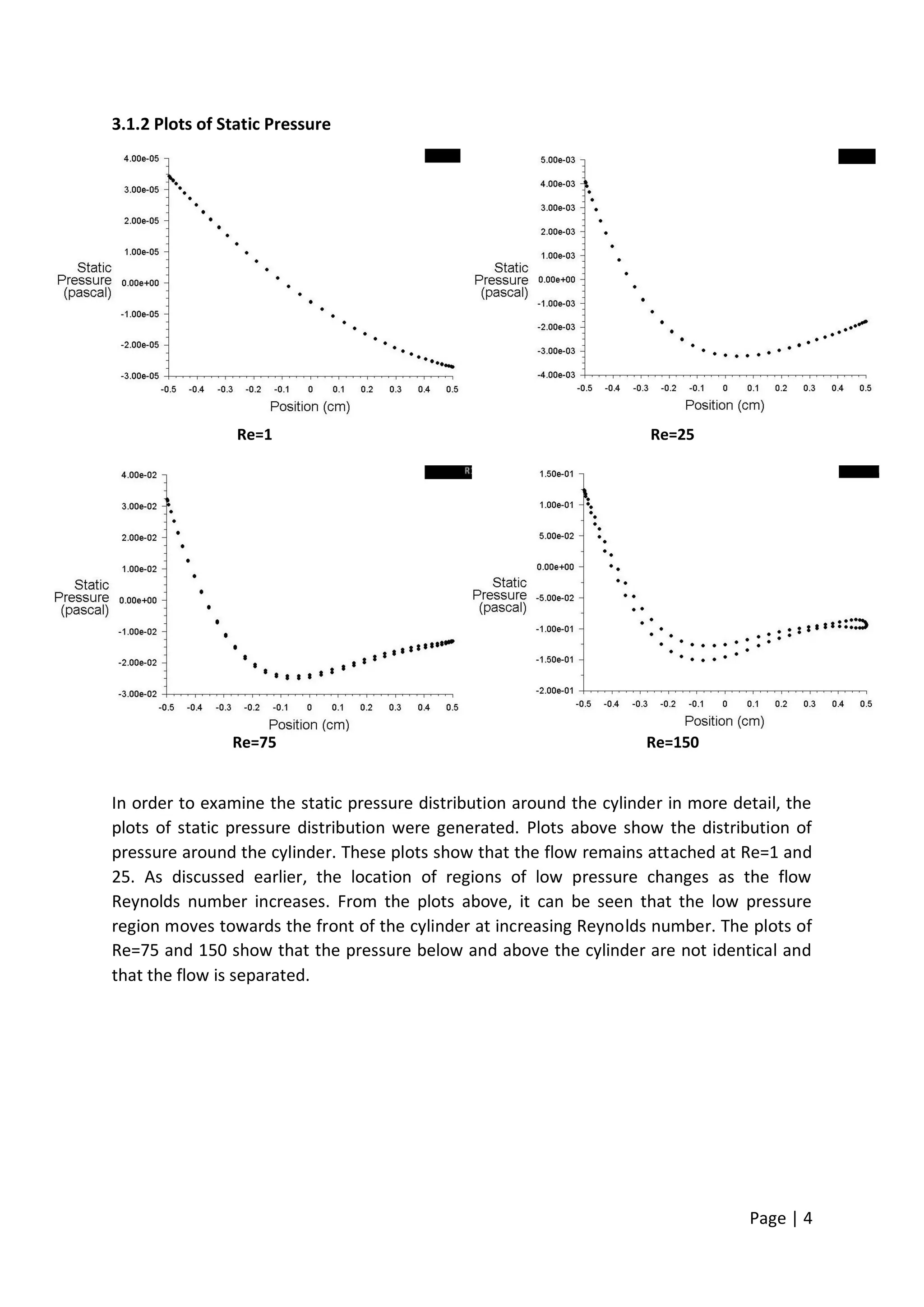

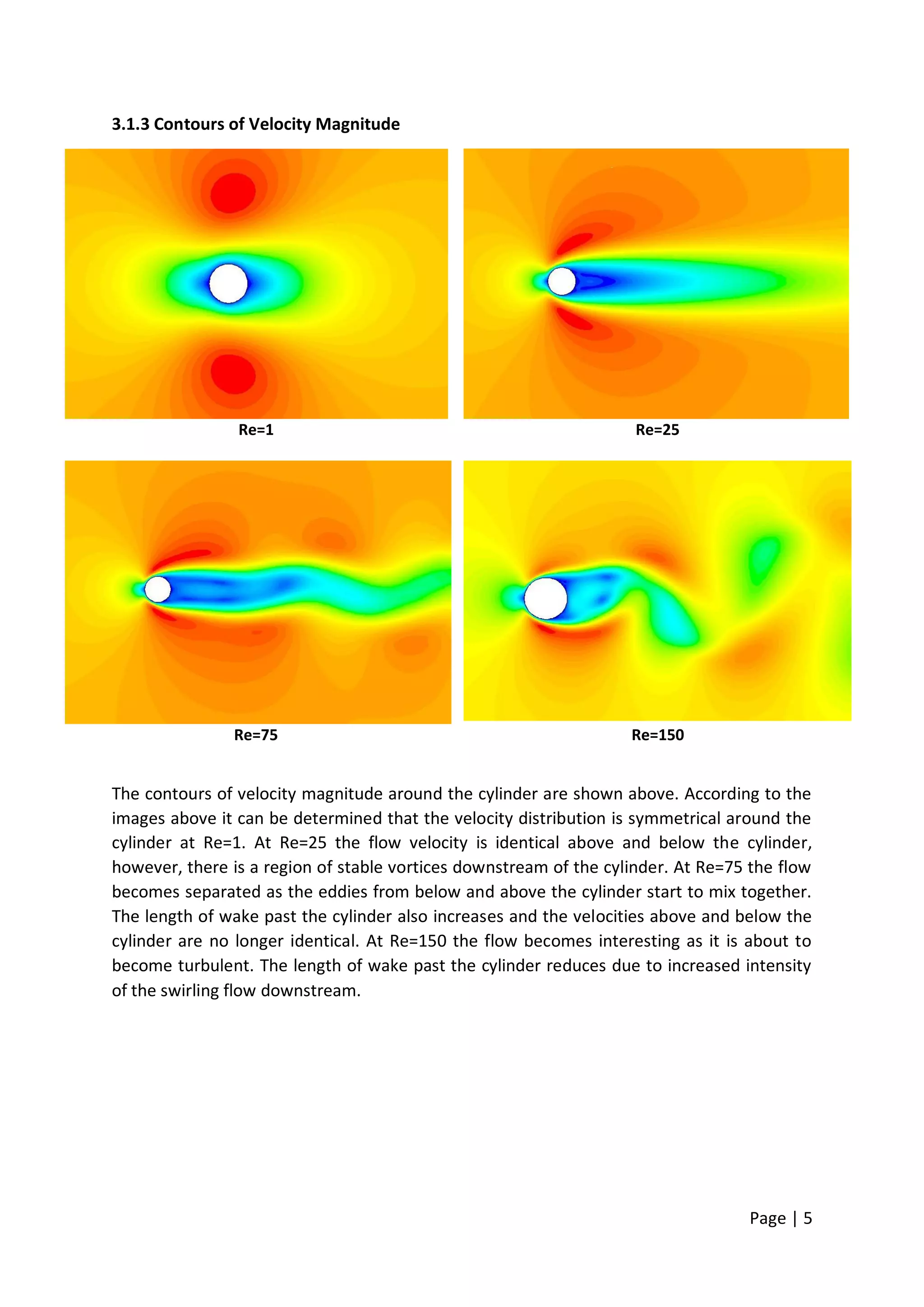

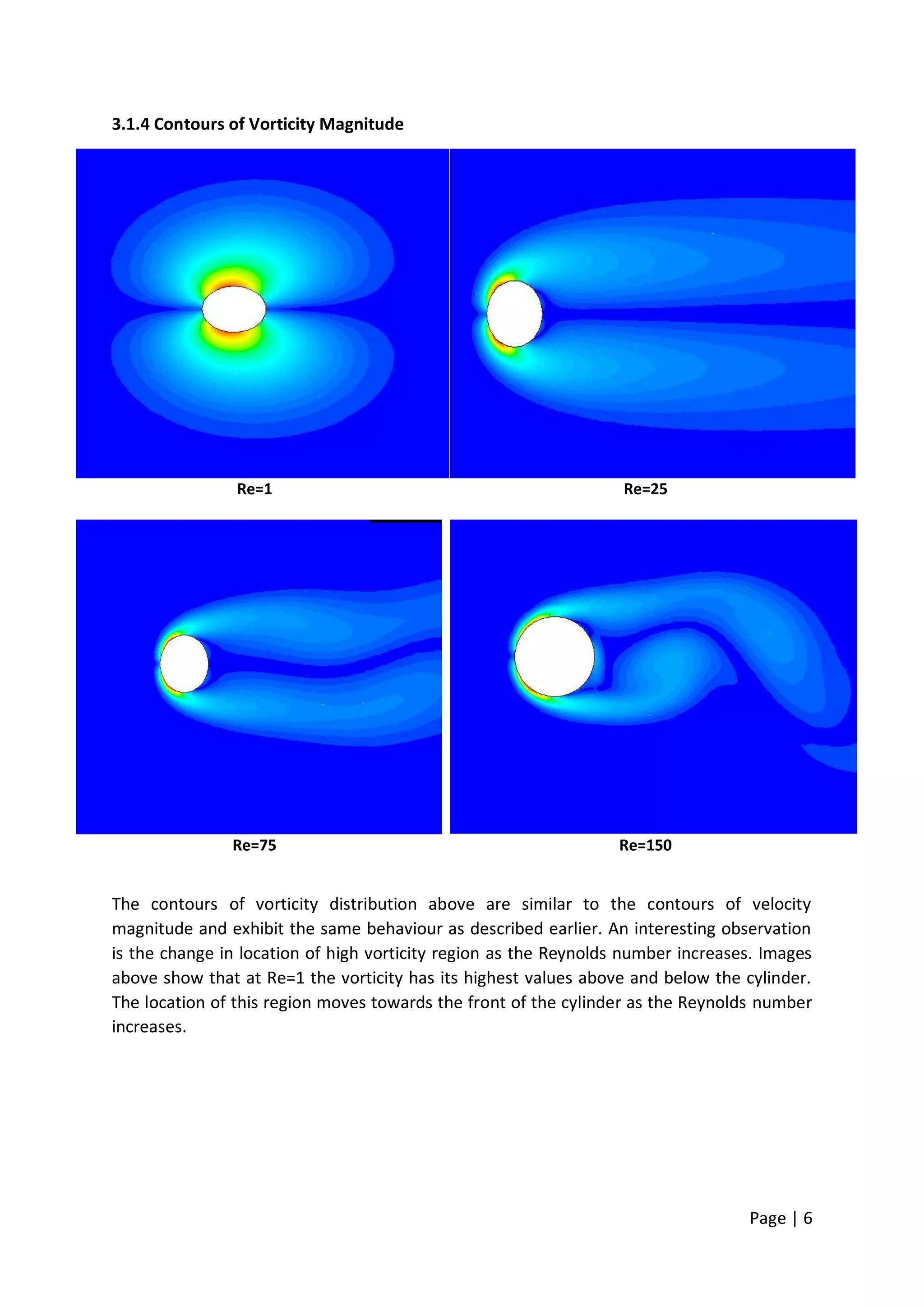

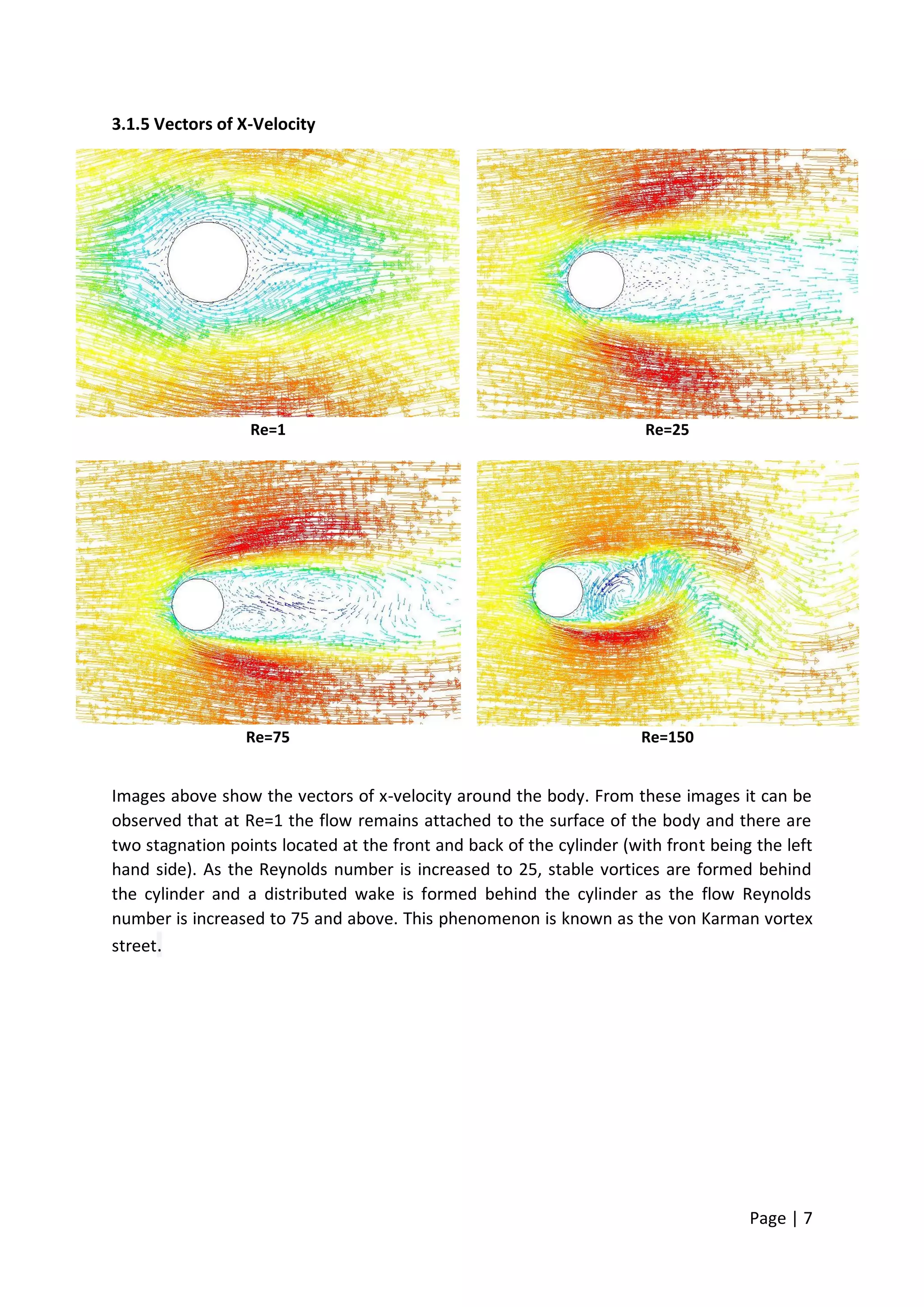

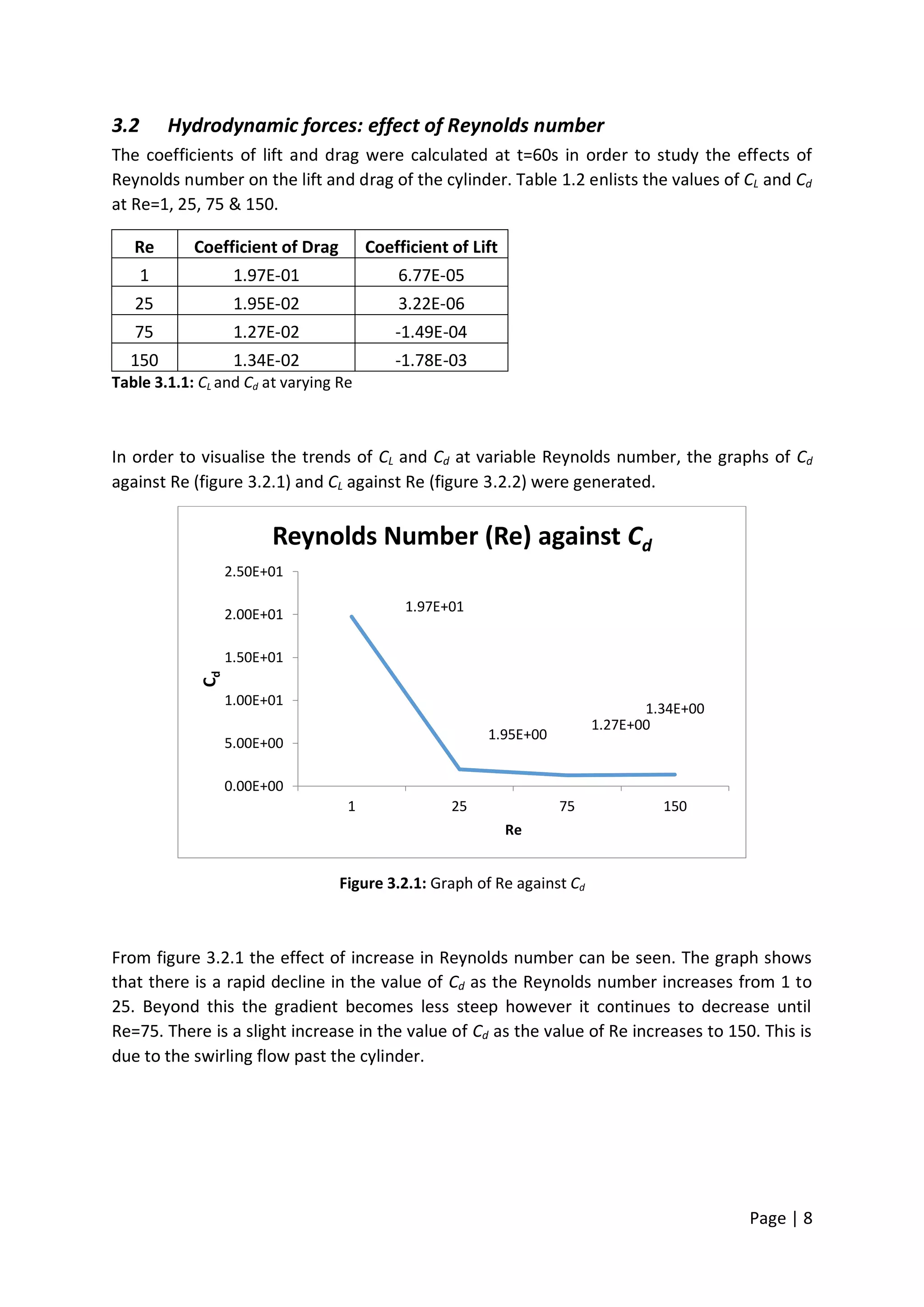

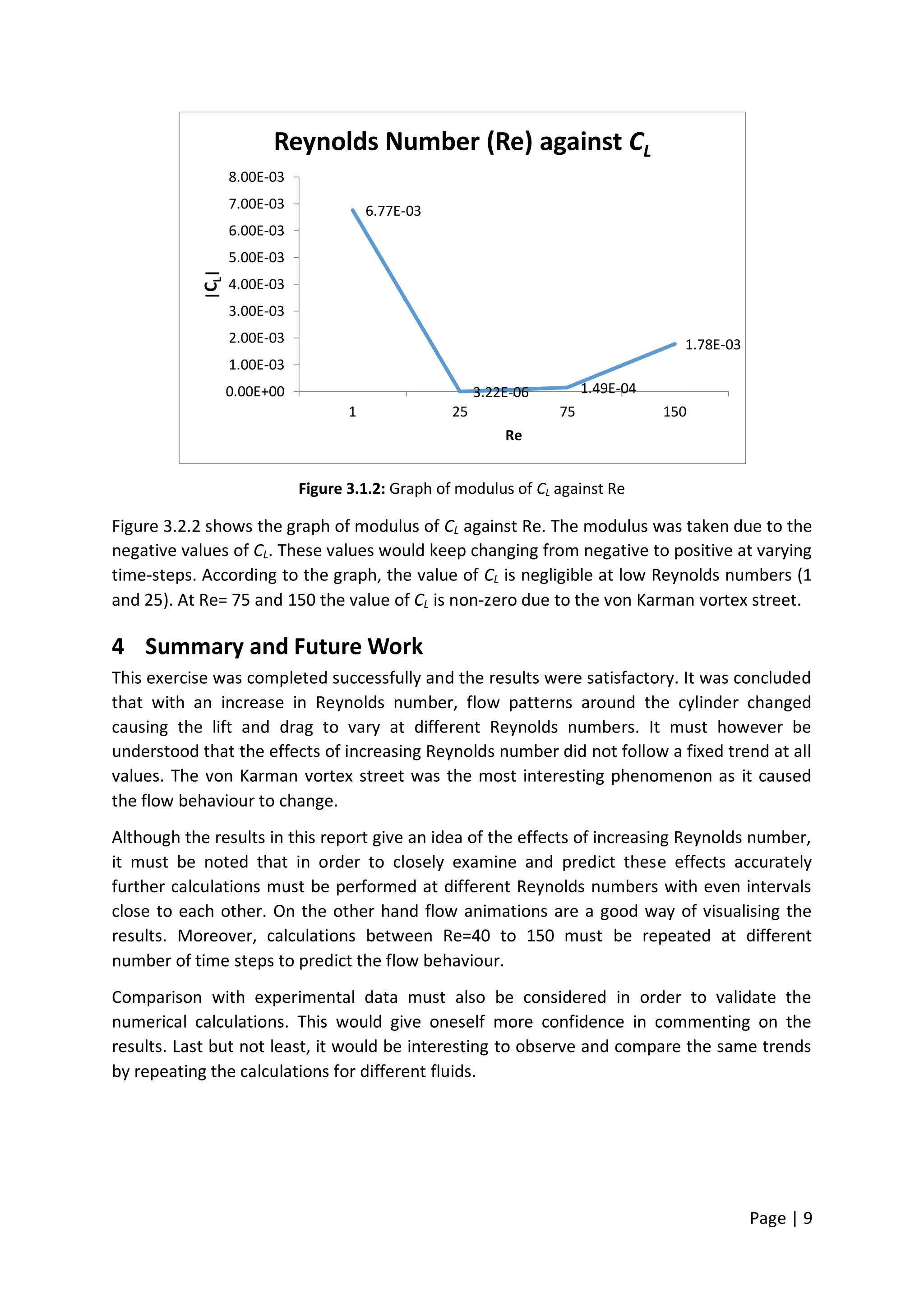

This document summarizes a computational fluid dynamics study of flow past a cylinder at moderate Reynolds numbers from 1 to 150. The study used the Fluent software to simulate the flow and examine the effects on flow patterns and hydrodynamic forces. As the Reynolds number increased, the flow transitioned from attached to separated flow with the formation of a von Karman vortex street. The drag coefficient decreased with Reynolds number until Re=75 then slightly increased at Re=150 due to swirling flow. The lift coefficient was negligible at low Re but increased at Re=75 and 150 due to vortex shedding.