This document provides an overview of an ophthalmology textbook. It includes information about the authors, contributors, publisher, and copyright details. The preface written by the lead author, Gerhard K. Lang, explains the educational goals behind creating the textbook - to engage medical students and sustain their interest in ophthalmology. A table of contents provides a high-level outline of the textbook's chapter structure and topics covered.

![II

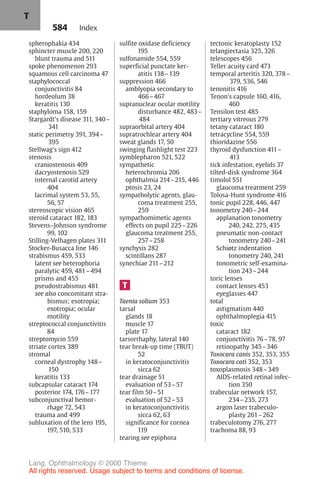

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publica-

tion Data

Lang, Gerhard K.

[Augenheilkunde. English]

Ophthalmology : a short textbook /

Gerhard K. Lang ; with contributions by

J. Amann... [et al.]. p. ; cm. Includes biblio-

graphical references and index.

ISBN 3131261617

1. Eye-Diseases. 2. Ophthalmology.

I. Amann, J. (Josef) II. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Eye Diseases.

WW 40 L269a 2000a]

RE46.L3413 2000

617.7–dc21 00-032597

Student contributors:

Christopher Dedner, Tübingen

Uta Eichler, Karlsruhe

Heidi Janeczek, Göttingen

Beate Jentzen, Husberg

Mathis Kayser, Freiburg

Kerstin Lipka, Kiel

Maren Molkewehrum, Kiel

Alexandra Ogilvie, Munich

Patricia Ogilvie, Würzburg

Stefan Rose, Oldenburg

Translated by John Grossman, Berlin,

Germany

This book is an authorized translation of the

German edition published and copyrighted

1998 by Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart,

Germany.

Drawings by Markus Voll, Fürstenfeldbruck

Important Note: Medicine is an ever-

changing science undergoing continual

development. Research and clinical

experience are continually expanding our

knowledge, in particular our knowledge of

proper treatment and drug therapy. Insofar

as this book mentions any dosage or appli-

cation, readers may rest assured that the

authors, editors, and publishers have made

every effort to ensure that such references

are in accordance with the state of knowl-

edge at the time of production of the book.

Nevertheless this does not involve,

imply, or express any guarantee or

responsibility on the part of the publishers

in respect of any dosage instructions and

forms of application stated in the book.

Every user is requested to examine care-

fully the manufacturers’ leaflets accom-

panying each drug and to check, if neces-

sary in consultation with a physician or

specialist, whether the dosage schedules

mentioned therein or the contraindications

stated by the manufacturers differ from the

statements made in the present book. Such

examination is particularly important with

drugs that are either rarely used or have

been newly released on the market. Every

dosage schedule or every form of applica-

tion used is entirely at the user’s own risk

and responsibility. The authors and pub-

lishers request every user to report to the

publishers any discrepancies or inaccura-

cies noticed.

! 2000 Georg Thieme Verlag

Rüdigerstraße 14

D-70469 Stuttgart, Germany

Thieme New York, 333 Seventh Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10001 U.S.A

Typesetting by Druckhaus Götz GmbH,

Ludwigsburg

Printed in Germany by

Appl, Wemding

ISBN 3-13-126161-7 (GTV)

ISBN 0-86577-936-8 (TNY) 1 2 3 4 5

Some of the product names, patents, and

registered designs referred to in this book

are in fact registered trademarks or pro-

prietary names even though specific refer-

ence to this fact is not always made in the

text. Therefore, the appearance of a name

without designation as proprietary is not to

be construed as a representation by the

publisher that it is in the public domain.

This book, including all parts thereof, is

legally protected by copyright. Any use,

exploitation, or commercialization outside

the narrow limits set by copyright legisla-

tion, without the publisher’s consent, is

illegal and liable to prosecution. This

applies in particular to photostat reproduc-

tion, copying, mimeographing or duplica-

tion of any kind, translating, preparation of

microfilms, and electronic data processing

and storage.

Lang, Ophthalmology © 2000 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorttexetlangophthalmology2000thieme-230914204815-6096f09f/85/ShortTexet-Lang-Ophthalmology-2000-Thieme-pdf-2-320.jpg)

![233

10 Glaucoma

Gerhard K. Lang

10.1 Basic Knowledge

Definition

Glaucoma is a disorder in which increased intraocular pressure damages the

optic nerve. This eventually leads to blindness in the affected eye.

❖ Primary glaucoma refers to glaucoma that is not caused by other ocular

disorders.

❖ Secondary glaucoma may occur as the result of another ocular disorder or

an undesired side effect of medication or other therapy.

Epidemiology: Glaucoma is the second most frequent cause of blindness in

developing countries after diabetes mellitus. Fifteen to twenty per cent of all

blind persons lost their eyesight as a result of glaucoma. In Germany, approxi-

mately 10% of the population over 40 has increased intraocular pressure.

Approximately 10% of patients seen by ophthalmologists suffer from glau-

coma. Of the German population, 8 million persons are at risk of developing

glaucoma, 800 000 have already developed the disease (i.e., they have glau-

coma that has been diagnosed by an ophthalmologist), and 80 000 face the

risk of going blind if the glaucoma is not diagnosed and treated in time.

Early detection of glaucoma is one of the highest priorities for the pub-

lic health system.

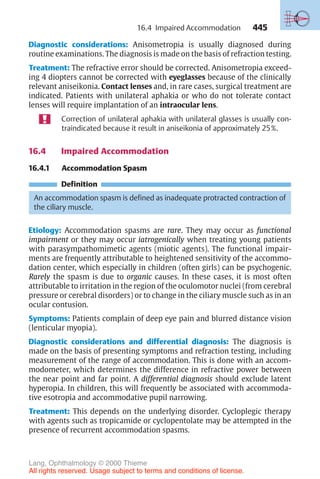

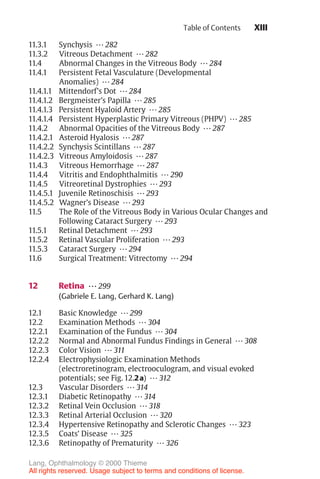

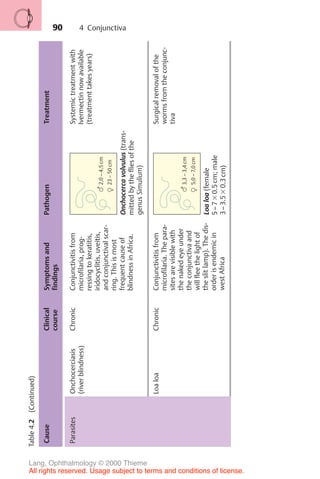

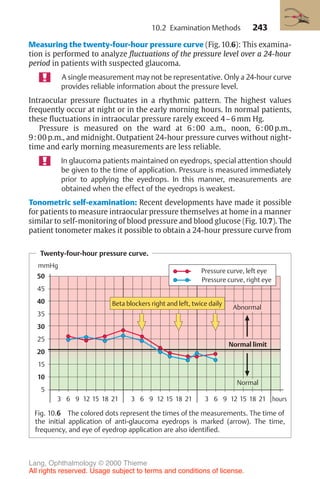

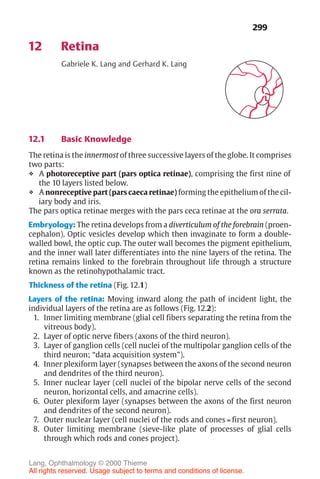

Physiology and pathophysiology of aqueous humor circulation (Fig. 10.1):

The average normal intraocular pressure of 15 mm Hg in adults is significantly

higher than the average tissue pressure in almost every other organ in the

body. Such a high pressure is important for the optical imaging and helps to

ensure several things:

❖ Uniformly smooth curvature of the surface of the cornea.

❖ Constant distance between the cornea, lens, and retina.

❖ Uniform alignment of the photoreceptors of the retina and the pigmented

epithelium on Bruch’s membrane, which is normally taut and smooth.

The aqueous humor is formed by the ciliary processes and secreted into the

posterior chamber of the eye (Fig. 10.1 [A]). At a rate of about 2–6 µl per

Lang, Ophthalmology © 2000 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorttexetlangophthalmology2000thieme-230914204815-6096f09f/85/ShortTexet-Lang-Ophthalmology-2000-Thieme-pdf-251-320.jpg)

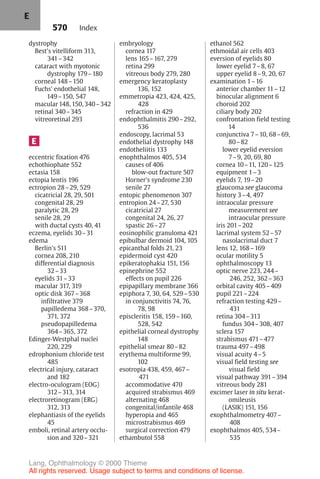

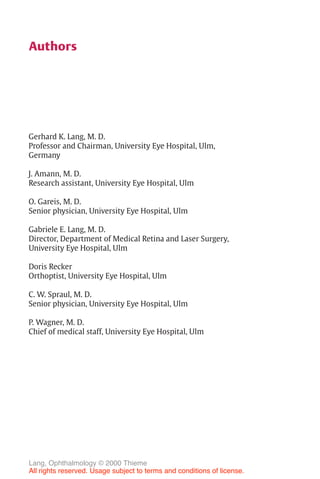

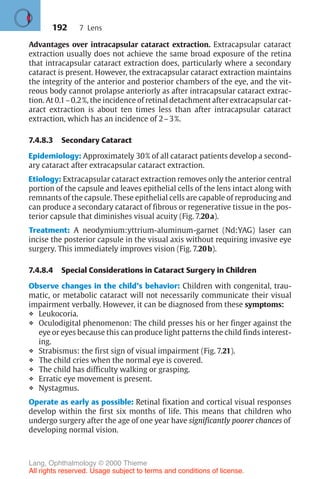

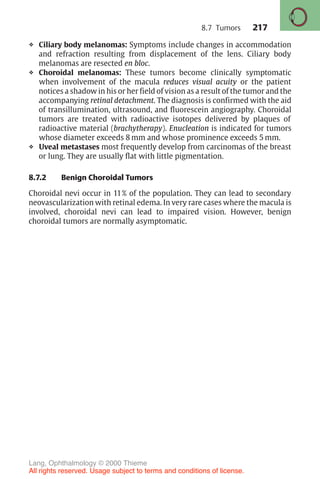

![234

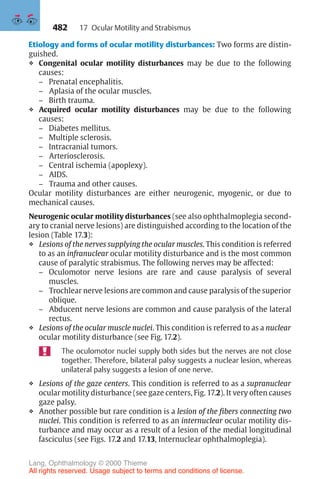

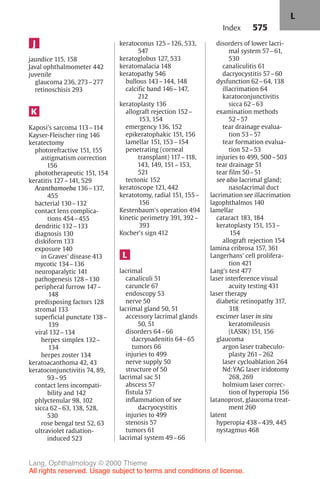

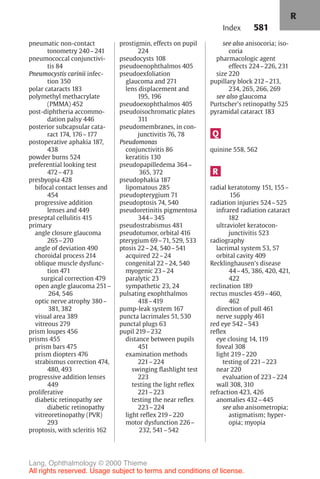

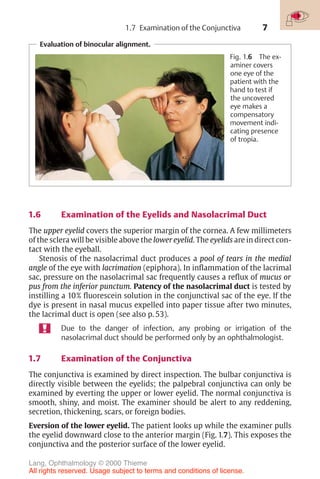

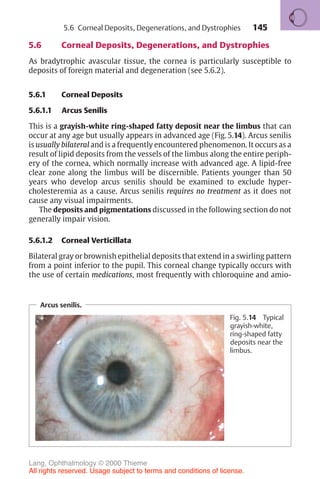

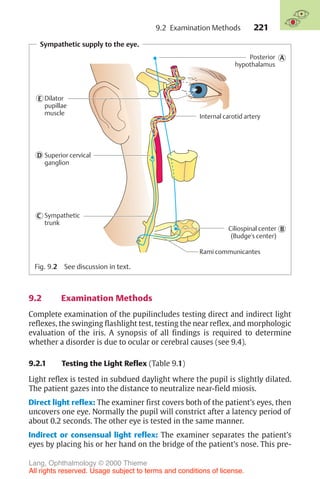

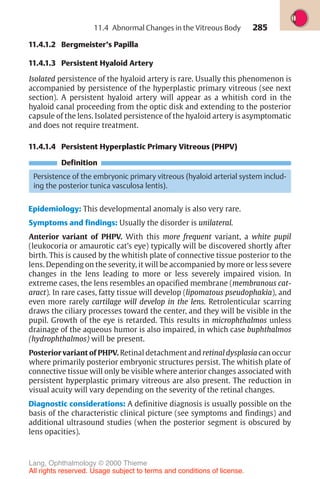

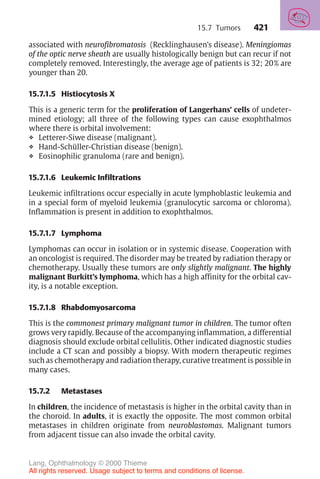

Physiology of aqueous humor circulation.

A

E

D

C

B

Ciliary body

Lens

Iris

Cornea

Canal of Schlemm

Trabecular meshwork

Collecting channel

Conjunctiva

Episcleral venous plexus

Fig. 10.1 As it flows from the nonpigmented cells of the ciliary epithelia A to

beneath the conjunctiva D , the aqueous humor overcomes physiologic resistance

from two sources: the resistance of the pupil B and the resistance of the trabecular

meshwork C .

minute and a total anterior and posterior chamber volume of about

0.2–0.4 ml, about 1–2% of the aqueous humor is replaced each minute.

The aqueous humor passes through the pupil into the anterior chamber. As

the iris lies flat along the anterior surface of the lens, the aqueous humor can-

not overcome this pupillary resistance (first physiologic resistance; Fig. 10.1

[B]) until sufficient pressure has built up to lift the iris off the surface of the

lens. Therefore, the flow of the aqueous humor from the posterior chamber

into the anterior chamber is not continuous but pulsatile.

Any increase in the resistance to pupillary outflow (pupillary block) leads to

an increase in the pressure in the posterior chamber; the iris inflates anteri-

orly on its root like a sail and presses against the trabecular meshwork (Table

10.2). This is the pathogenesis of angle closure glaucoma.

Various factors can increase the resistance to pupillary outflow (Table

10.1). The aqueous humor flows out of the angle of the anterior chamber

through two channels:

❖ The trabecular meshwork (Fig. 10.1 [C]) receives about 85% of the out-

flow, which then drains into the canal of Schlemm. From here it is con-

10 Glaucoma

Lang, Ophthalmology © 2000 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorttexetlangophthalmology2000thieme-230914204815-6096f09f/85/ShortTexet-Lang-Ophthalmology-2000-Thieme-pdf-252-320.jpg)

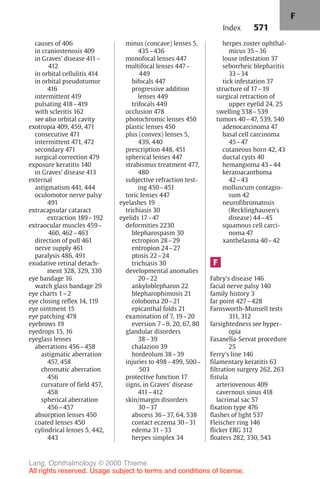

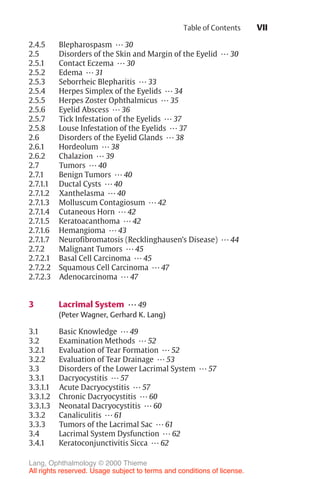

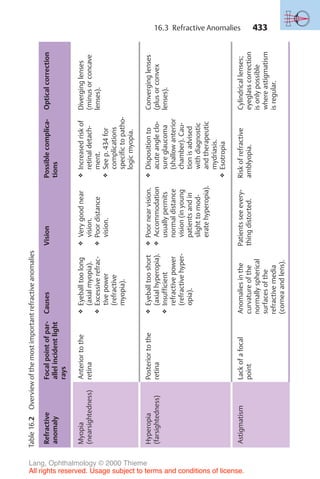

![443

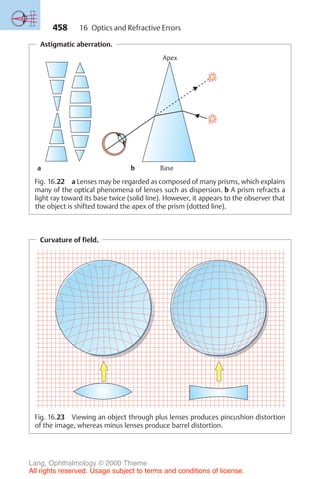

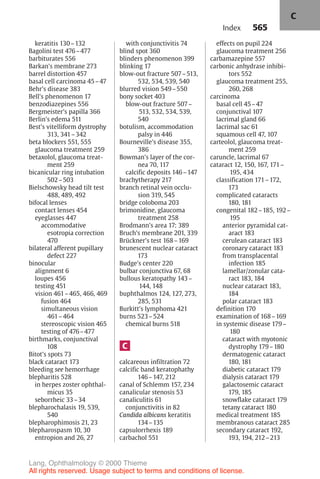

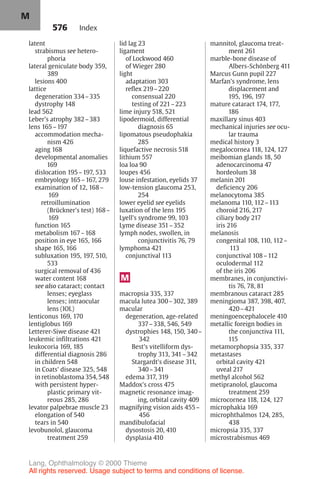

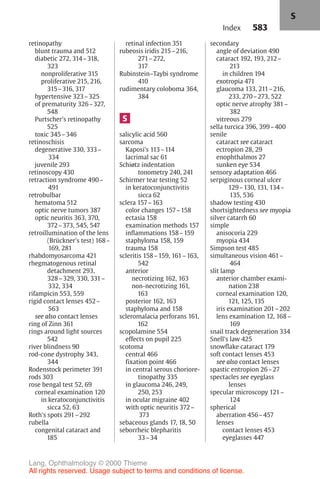

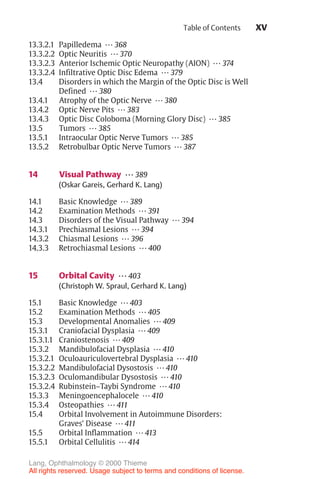

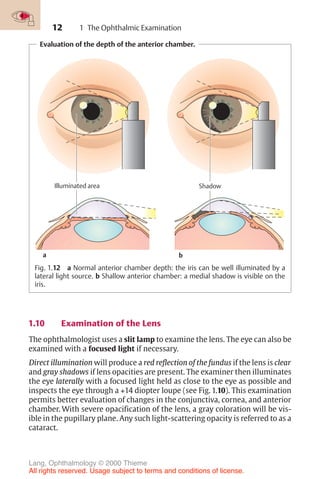

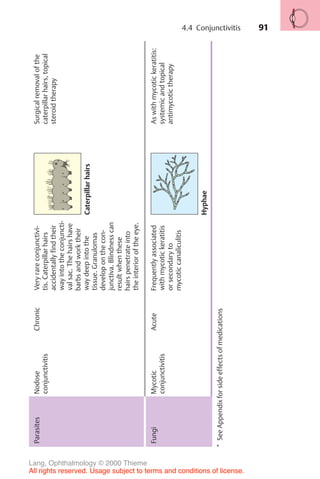

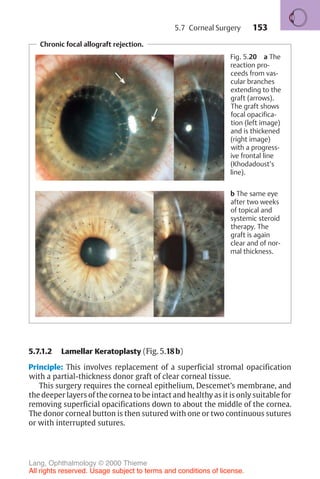

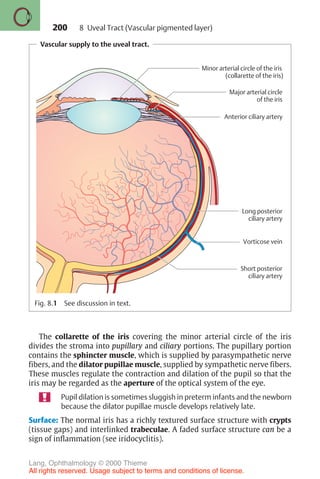

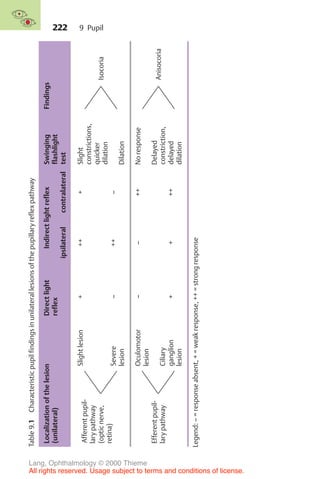

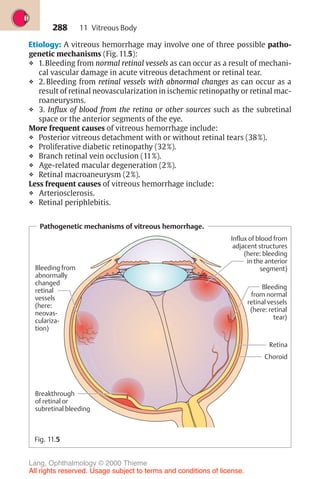

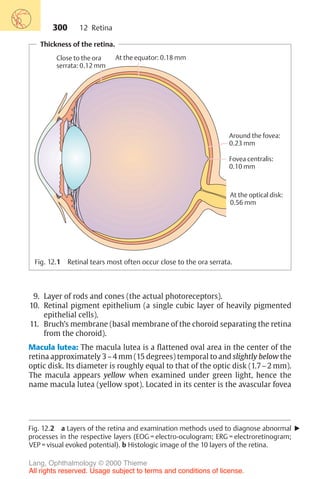

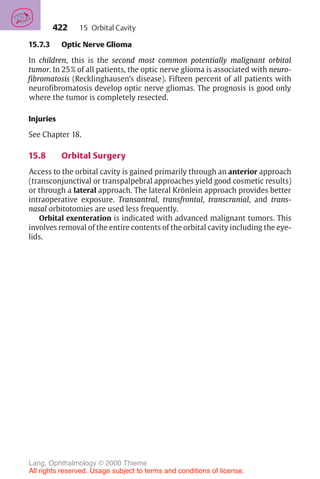

Diagnosis of corneal astigmatism with an ophthalmometer.

1 2

1 2

Fig. 16.14 The diagram shows the corneal reflex images (outline cross [1] and solid

cross [2]) of the Zeiss ophthalmometer. These images are projected on to the cor-

nea; the distance between them will vary depending on the curvature of the cornea.

The examiner must align the images by changing their angle of projection. After

aligning them, the examiner reads the axis of the main meridian, the corneal curva-

ture in millimeters, and the appropriate refractive power in diopters on a scale in the

device. This measurement is performed in both main meridians. The difference

yields the astigmatism. In irregular astigmatism, the images are distorted, and often

a measurement cannot be obtained.

Correction of regular astigmatism with cylinder lenses.

0

0

90°

90°

180

180

a

b

c

d

Fig. 16.15 a Cyl-

inder lenses refract

light only in the

plane perpendicu-

lar to the axis of

the cylinder. The

axis of the cylinder

defines the nonre-

fracting plane.

b–d Cylinder

lenses can be man-

ufactured as plus

cylinders (c) or

minus cylinders

(d).

16.3 Refractive Anomalies

Lang, Ophthalmology © 2000 Thieme

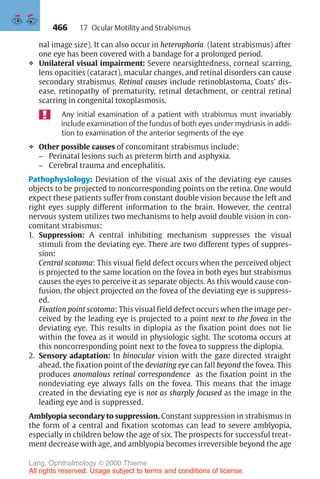

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shorttexetlangophthalmology2000thieme-230914204815-6096f09f/85/ShortTexet-Lang-Ophthalmology-2000-Thieme-pdf-461-320.jpg)