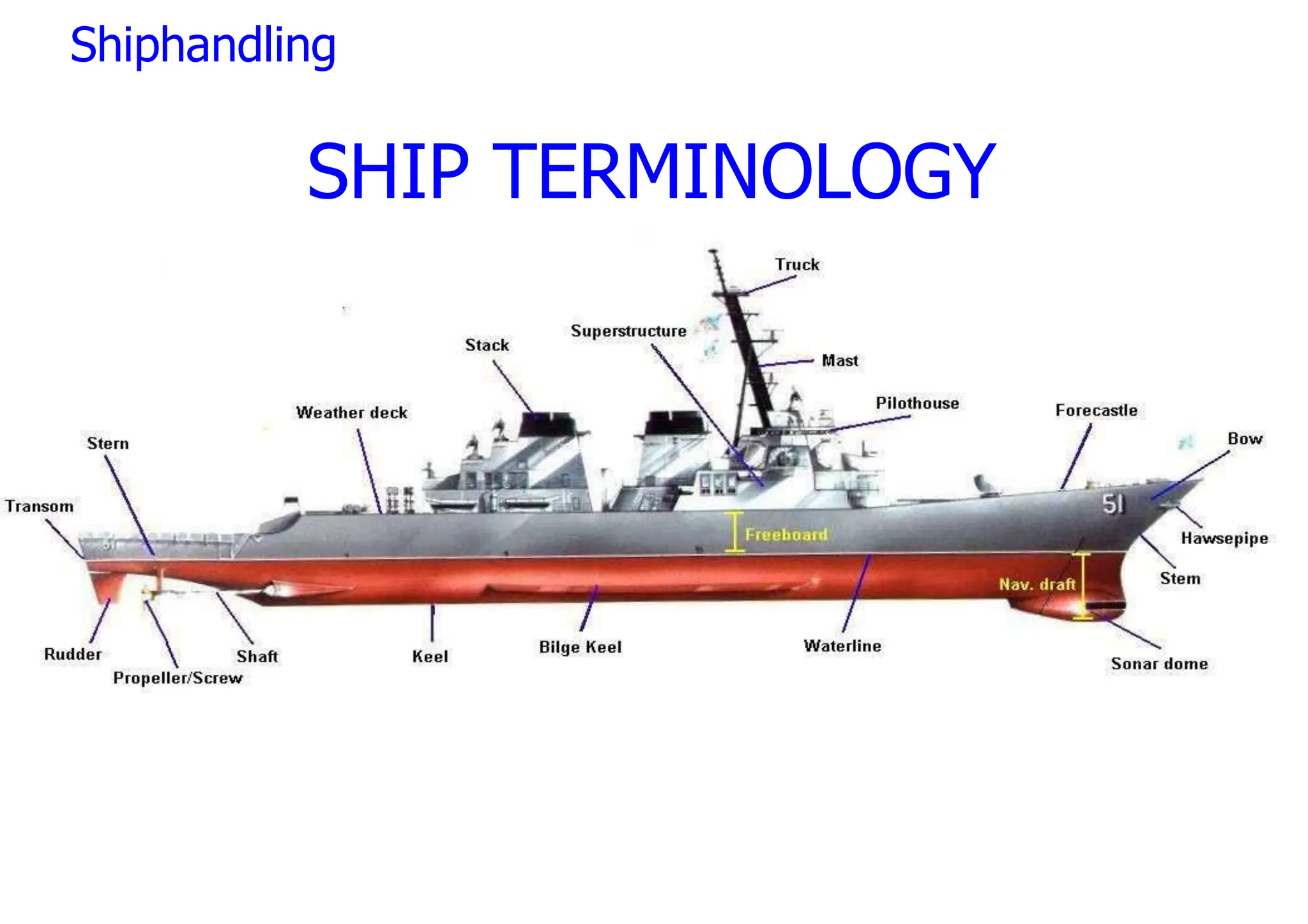

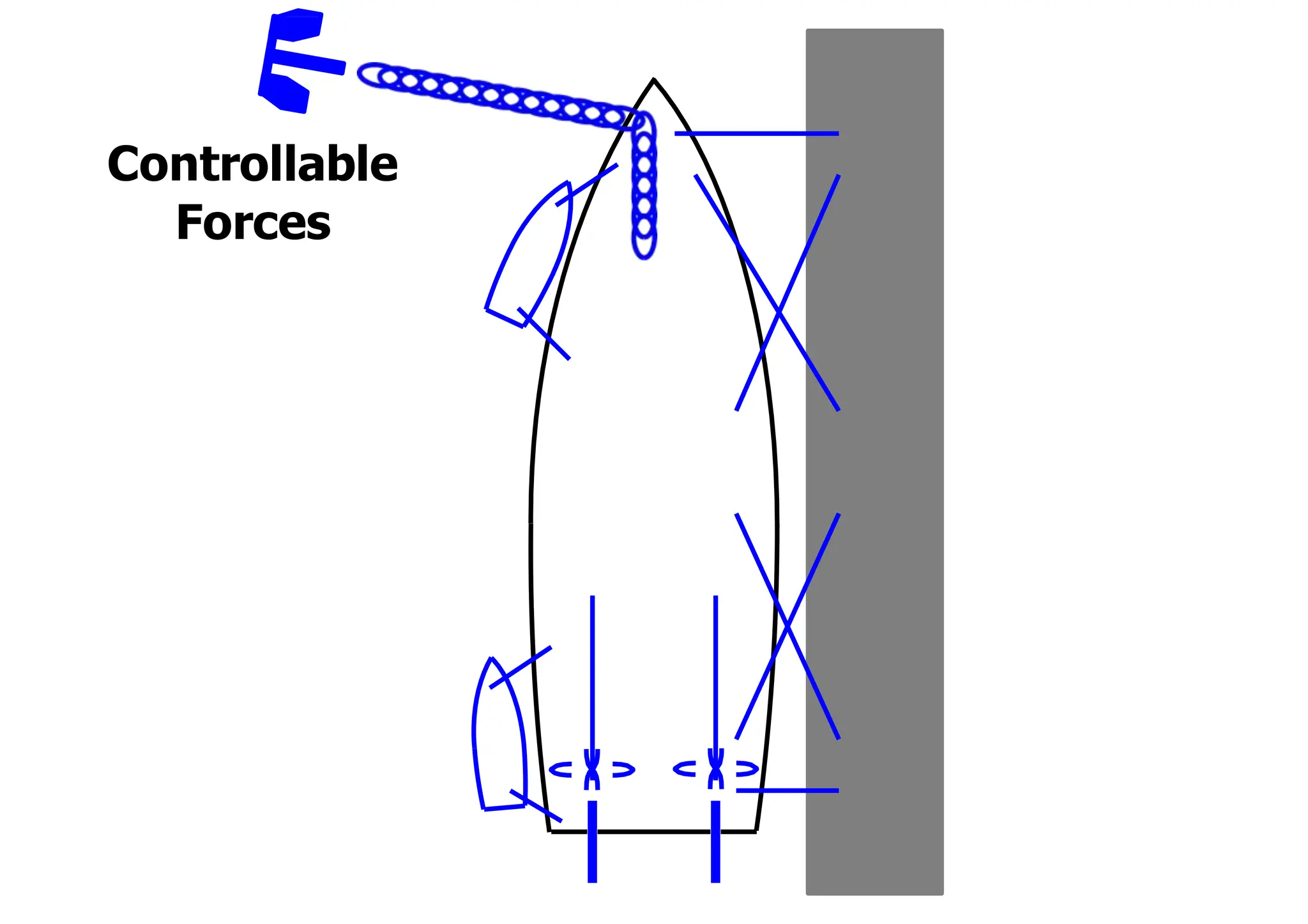

This document provides information about ship maneuvering, including terminology, forces, and concepts. It defines key ship parts like the bow, stem, and superstructure. It describes controllable forces from propellers, rudders, and mooring lines that can maneuver a ship. Uncontrollable forces from wind, current, and water depth are also discussed. The concept of the pivot point is explained, which is the point about which a ship rotates during maneuvers and is affected by factors like headway, speed, and tugs. Basic shiphandling theory on motion and Newton's laws is presented.

![̏ ̓

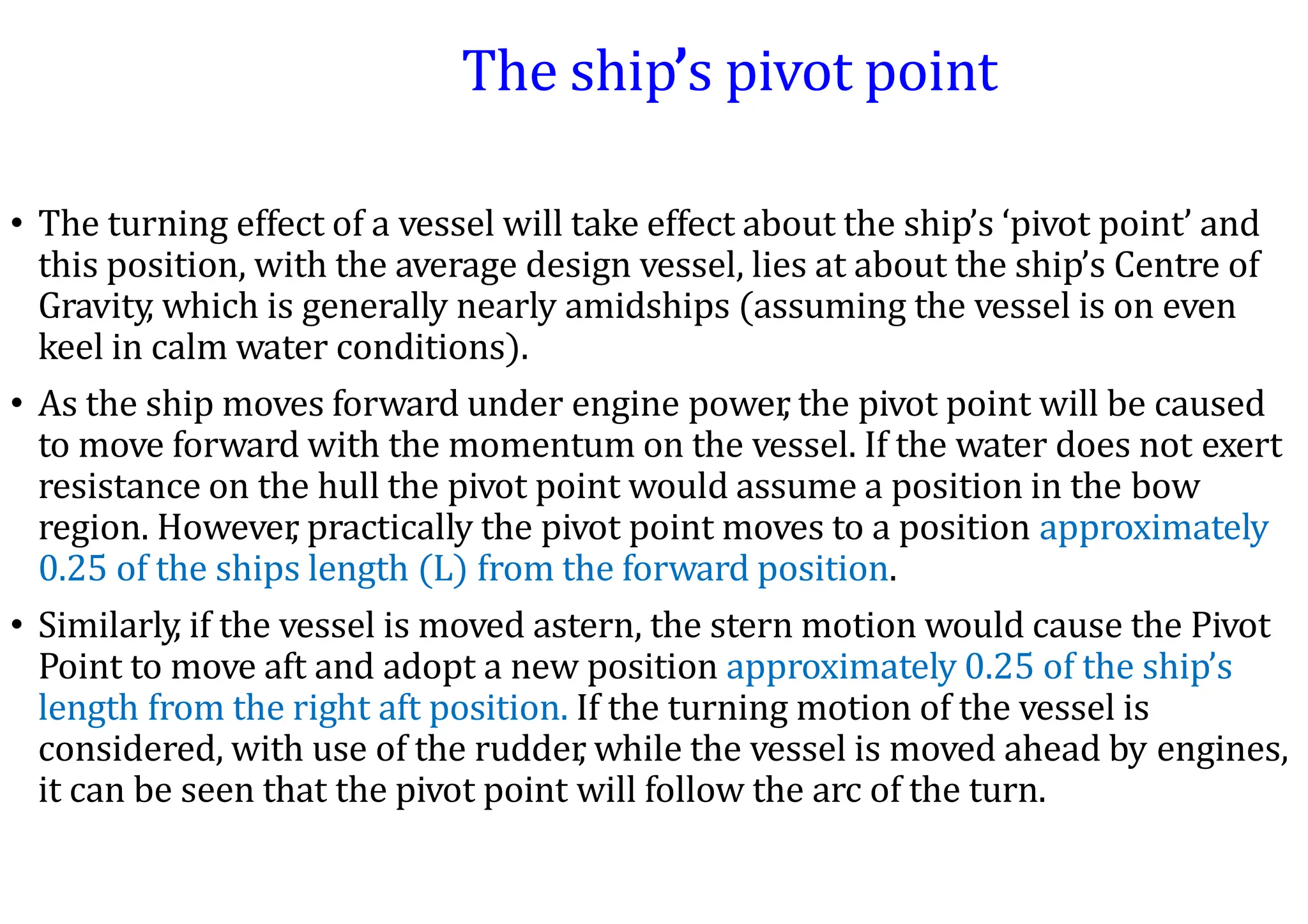

= Advantages and disadvantages of the parallel approach =

[Advantages]

• While this depends on the layout of the pier, a mistake in reducing

speed does not result in damage to the pier

. When the pier is of

considerable length, a mistake in speed control simply results in

overrunning the scheduled stop position, and does not result in

damage to the pier

.

• With the conventional method, container ships etc. with large bow

flares sometimes damage cranes etc. overhanging the pier.

This risk is much reduced with the parallel approach.

• The attitude of the vessel is more easily controlled with the parallel

approach, facilitating response to rapid changes in external forces.

[Disadvantages]

• An extra 10 – 20 minutes is required to reach the pier

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shiphandlingandmanoeuveringbasics-240315023512-20982837/75/SHIP-HANDLING-AND-MANOEUVERING-BASICS-pptx-241-2048.jpg)

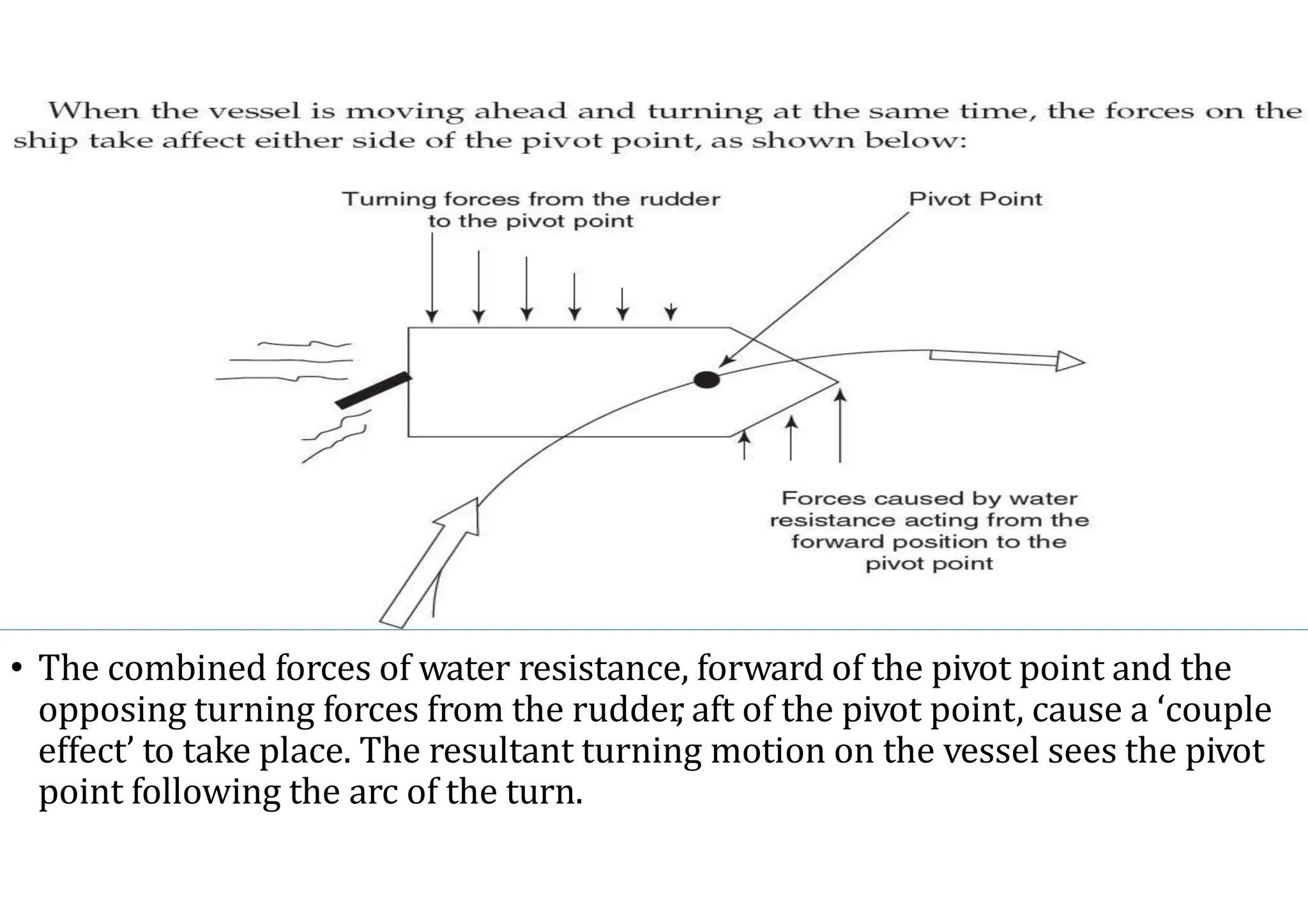

![· The First Stage : Dragging Anchor with Yaw and Sway

Yaw and sway motion of a vessel when

lying to an anchor is sometimes referred

to as “horsing”. Area [A] in the diagram

shows the situation where the ship is lying

at anchor and yawing in a “figure-of-eight”

motion.

It has been found that as wind pressure

force begins to exceed the anchor’s

holding power, the ship yaws and is

pressed to leeward, as shown by area [B]

in the diagram.

It is suggested that, during this period, it should be

relatively easy to control the maneuverability of a ship in

such a state and to weigh the anchor.

̐̔](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shiphandlingandmanoeuveringbasics-240315023512-20982837/75/SHIP-HANDLING-AND-MANOEUVERING-BASICS-pptx-252-2048.jpg)

![· The Second Stage : Anchor Dragging caused by Wind Pressure

Where wind pressure force gradually becomes stronger, one

side of the ship turns against the wind and is then pressed and

moves to leeward at a certain speed, as shown in area [C] in

the diagram.

It is suggested that, during this stage, it is difficult to weigh

anchor and, even if possible, this takes a considerable amount

of time. If weighing the anchor cannot be accomplished, the

ship loses its maneuverability.

Dragging anchor may not be detected by the Traditional

Methods until the vessel has entered the second stage

described above, by which time it may be too late to avoid a

dangerous situation from developing.

̐̕](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shiphandlingandmanoeuveringbasics-240315023512-20982837/75/SHIP-HANDLING-AND-MANOEUVERING-BASICS-pptx-253-2048.jpg)

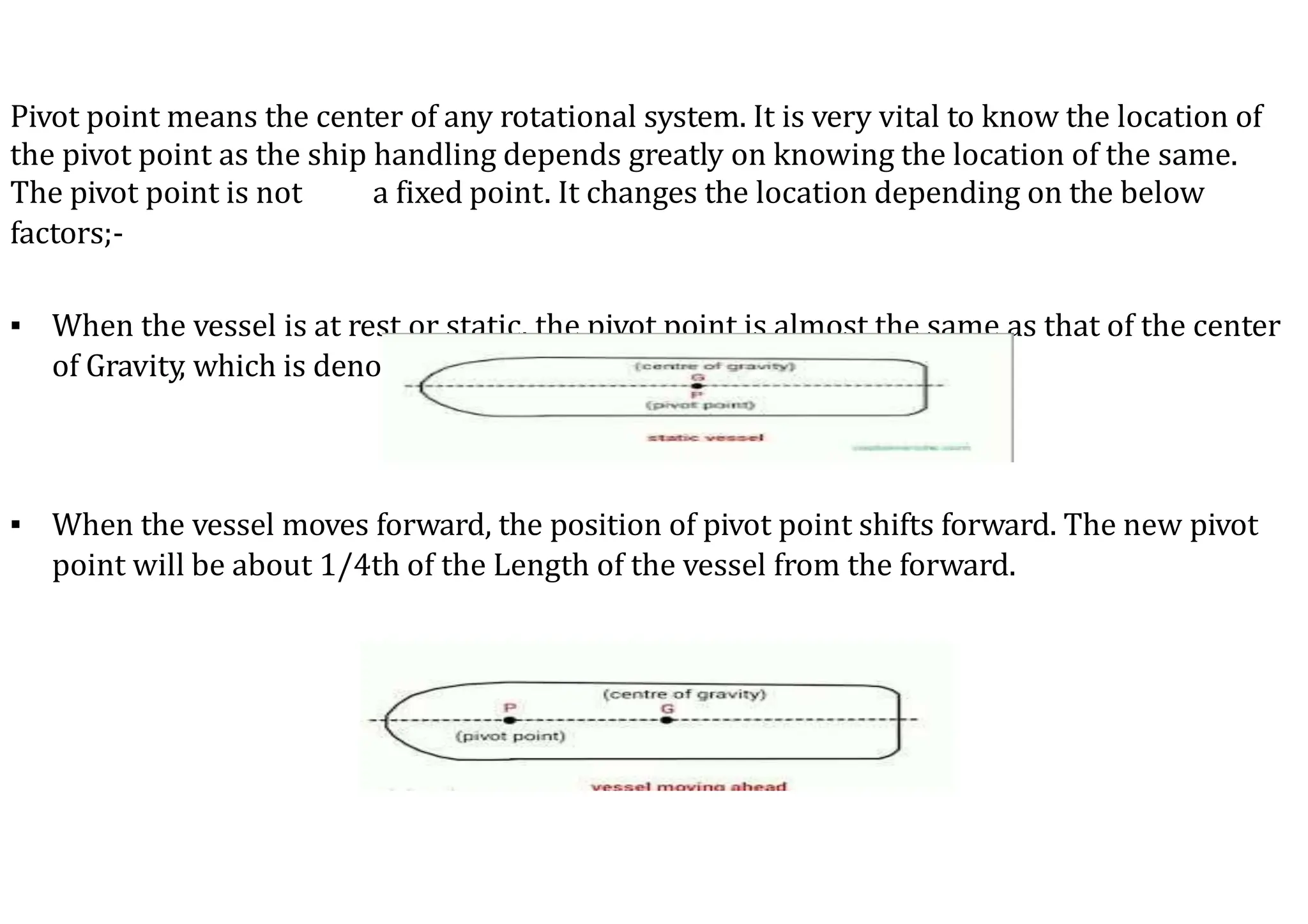

7B : Headwind speed [m/sec]

ρ : Air density [0.125kg ɾ sec2 /m4 ]

A. : Ship’s projected area from bow above waterline [m2]

B. : Ship’s projected area from side above waterline [m2]

a : Length from bow to wind pressure center [m] (Point of

Action )

RB : Resultant wind pressure force[kg] → divided by

1,000 to be “ton” ( Total Wind Force )

α : Wind pressure force angle[ degree]( Angle of Action )

CRa : Wind pressure force coefficient.

Passenger : 1.142 - 0.142cos2В 0.367cos4В- 0.133cos6В

General Cargo : 1.325 - 0.050cos2В- 0.350cos4В- 0.175cos6В

Tanker & Bulk carrier

: 1.200 - 0.083cos2В- 0.250cos4В- 0.117cos6В

Resultant wind pressure force is proportional to the square of wind speed.

3B ͇Л͇$ 3BY7B Y" DPT Вʴ̗ TJ

O Вʣ U

PO

̑̍](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shiphandlingandmanoeuveringbasics-240315023512-20982837/75/SHIP-HANDLING-AND-MANOEUVERING-BASICS-pptx-255-2048.jpg)

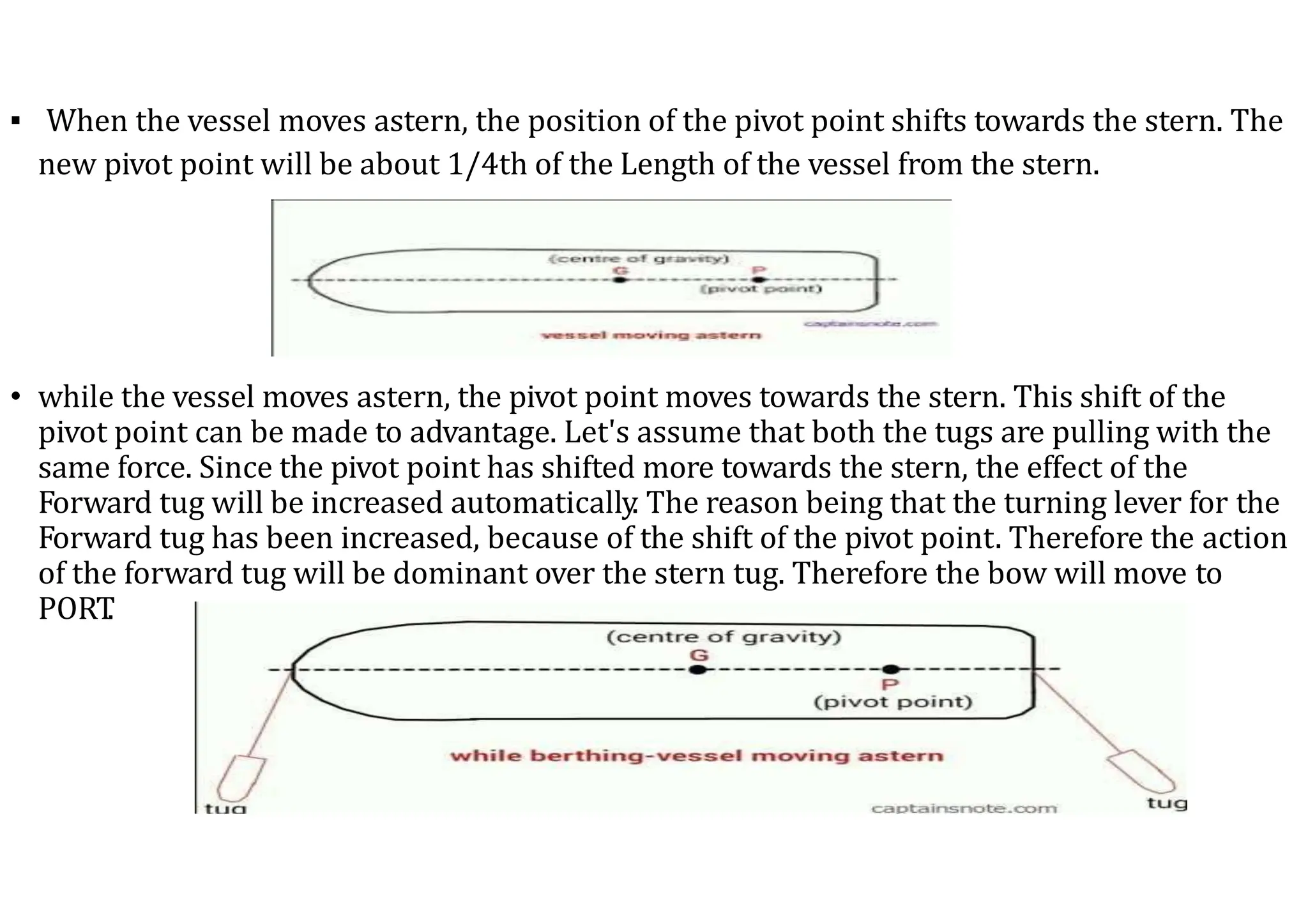

![Calculating the Catenary Length of an Anchor Chain

5Y

8 D

̨ ʹ ͈2

ʴ Z

S : Catenary length against the external force (m)

Z : Water Depth + Hawsepipe height from sea surface (m)

Wc’ : Anchor Chain Weight per m in Water (kgs)

= 0.87 x Wc (kgs)

Tx : External force (kgf)

Under the condition that L [Minimum Required Length of Anchor

Chain (S + l ) ] is fixed at a certain level, if Tx [External force (kgf) ]

increases, S [Catenary length against the external force(m) ] will

also increase.

On the contrary, however, l

[Minimum Required Contacted

length of the chain (m) ] decreases

so that H[Holding power created by

Anchor and Anchor Chain (kgs) ]

will be diminished.

̑̐](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shiphandlingandmanoeuveringbasics-240315023512-20982837/75/SHIP-HANDLING-AND-MANOEUVERING-BASICS-pptx-258-2048.jpg)

![What About the Engines Stopping or Reversing?

Trimmer Thomas Dillon: "They stopped...about a minute and a half [after the collision]. They

[then] went slow astern ... about a minute and a half [later for] about two minutes."

Greaser Thomas Ranger: "We turned round and looked into the engine room and saw the turbine

engine was stopped...There are two arms [that] come up as the turbine engine stops...

[that was] about two minutes afterwards...[after the jar.]"

1st Class Passenger Henry Stengel: "As I woke up I heard a slight crash. I paid no attention to it

until I heard the engines stop...[They were stopped] I should say two or three minutes, and then

they started again just slightly; just started to move again. I do not know why; whether they were

backing off, or not."

1st Class Passenger George Rheims: "I did not notice that the engines were stopped right away;

they were not stopped right away; of that I am positive.

[I felt a change with reference to the engines] a few minutes after the shock, possibly two or three

minutes; might have been less."

2nd Class Passenger Lawrence Beesley: "There came what seemed to me nothing more than an

extra heave of the engines and a more than usually obvious dancing motion of the mattress... and

presently the same thing repeated with about the same intensity...I continued my reading...But in

a few moments I felt the engines slow and stop."

The engines did not stop nor reverse until some short

amount of time after the ship struck the iceberg.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shiphandlingandmanoeuveringbasics-240315023512-20982837/75/SHIP-HANDLING-AND-MANOEUVERING-BASICS-pptx-296-2048.jpg)

![Reality and Contradiction

QM HICHENS AT THE AMERICAN INQUIRY

QM Hichens: "The sixth officer repeated the order, "The helm is hard astarboard,

sir." But, during the time, she was crushing the ice, or we could hear the grinding

noise along the ship's bottom. I heard the telegraph ring, sir."

QM HICHENS' FIRST RESPONSE AT THE BRITISH INQUIRY

951. Had you time to get the helm hard a starboard before she struck? - [QM

Hichens] No, she was crashing then.

QM HICHENS' CONTRADICTION

957. Before the vessel struck had you had time to get the wheel right over? - [QM

Hichens] The wheel was over then, hard over.

958. (The Commissioner.) Before she struck? - Oh yes, hard over before she struck.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shiphandlingandmanoeuveringbasics-240315023512-20982837/75/SHIP-HANDLING-AND-MANOEUVERING-BASICS-pptx-301-2048.jpg)

![Time From 3-Bell Lookout Warning to Collision

Lookout Fredrick Fleet: "I saw this black thing looming up; I didn’t know what it was. I asked

Lee if he knew what it was. He couldn’t say. I thought I better ring the bell. I rang it three

times." [Interview with Leslie Reade]

QM Robert Hichens: "[The first notice that there was something ahead was] three gongs from the

crow's-nest, Sir...Well, as near as I can tell you, [it was] about half a minute [before the order came

'Hard-astarboard']." [British Inquiry 969-973]

QM Alfred Olliver: "When I was doing this bit of duty I heard three bells rung up in the crow's

nest, which I knew that it was something ahead...When I heard the report, I looked, but could

not see anything, and I left that and came was just entering on the bridge just as the shock

came." [American Inquiry]

IT TAKES ABOUT 45 SECONDS ON AVERAGE TO WALK FROM THE STANDARD

COMPASS PLATFORM TO THE BRIDGE NOT COUNTING REACTION TIME.

Time from 3-bell lookout warning to collision would be about 50-60

seconds based on QM Olliver's reported actions.

Iceberg spotted some short time earlier by Frederick Fleet.

We really don't know what time Murdoch first spotted the iceberg.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/shiphandlingandmanoeuveringbasics-240315023512-20982837/75/SHIP-HANDLING-AND-MANOEUVERING-BASICS-pptx-304-2048.jpg)