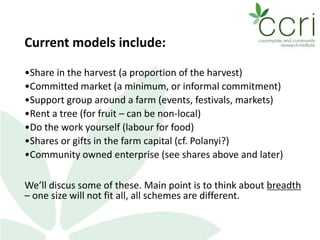

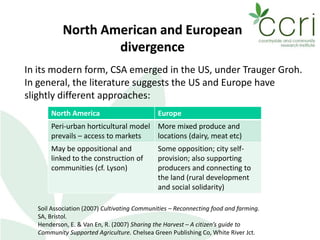

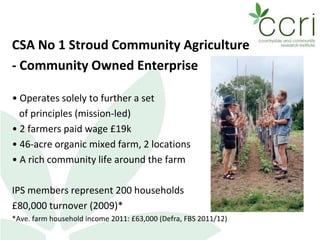

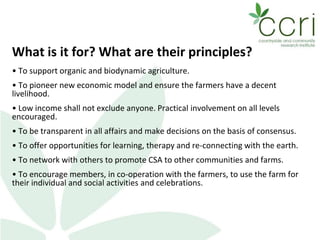

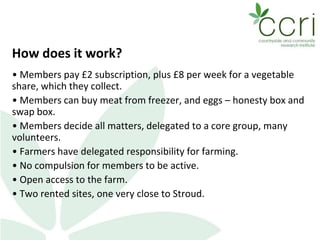

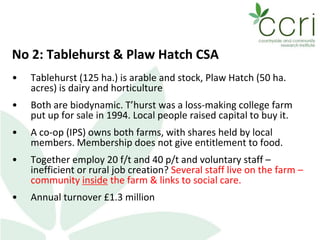

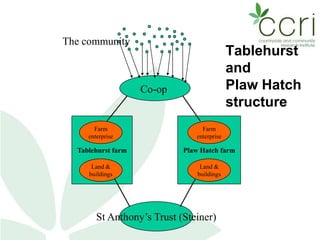

Community-supported agriculture (CSA) models emerged in response to concerns about the modern industrial food system and national food security. CSA aims to reconnect consumers and producers by having community members share the risks of food production through advance payments to farmers. This session reviewed different CSA structures in the UK, including community-owned cooperatives and farms that provide members with a share of produce. While CSAs promote alternative and localized approaches to food, their marginal scale and complex operations present challenges to significantly changing the mainstream food system.