The document provides an overview of topics covered in an iOS application development course on Objective-C basics. The topics include Objective-C introduction, creating a first Objective-C program, variables and data types, basic statements, conditional statements, loops, arrays, functions, exceptions, and pointers. The document contains code examples for many of these concepts.

![#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

!

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool

{

char charType = 'A';

double doubleType = 9200.8;

// Casting double value to int value

int intType = (int)doubleType;

id idType = @"Hello World";

NSLog(@"Character value: %c", charType);

NSLog(@"Double value: %.1f", doubleType); // 9200.8

NSLog(@"Integer value: %d", intType); // 9200

NSLog(@"id value: %p", idType);

NSLog(@"id type description: %@", [idType description]);

}

return 0;

}

!

Variables Example](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session2-objective-cbasics-140317160531-phpapp02/85/Session-2-Objective-C-basics-16-320.jpg)

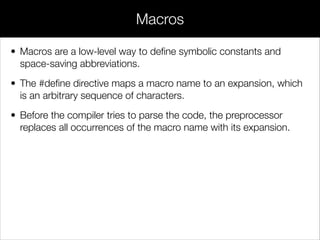

![#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

!

// Define macros

#define PI 3.14159

#define RAD_TO_DEG(radians) (radians * (180.0 / PI))

!

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool

{

double angle = PI / 2; // 1.570795

NSLog(@"%f", RAD_TO_DEG(angle)); // 90.0

}

return 0;

}

Macros](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session2-objective-cbasics-140317160531-phpapp02/85/Session-2-Objective-C-basics-21-320.jpg)

![• The typedef keyword lets you create new data types or redefine existing

ones.

• After typedef’ing an unsigned char in following example, we can use

ColorComponent just like we using char, int, double, or any other built-in

type:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

!

typedef unsigned char ColorComponent;

!

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool

{

ColorComponent red = 255;

ColorComponent green = 160;

ColorComponent blue = 0;

NSLog(@"Your paint job is (R: %hhu, G: %hhu, B: %hhu)", red, green, blue);

}

return 0;

}

Typedef](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session2-objective-cbasics-140317160531-phpapp02/85/Session-2-Objective-C-basics-22-320.jpg)

![• A struct is like a simple, primitive C object. It lets you aggregate several

variables into a more complex data structure, but doesn’t provide any OOP

features (e.g., methods).

• For following example, allow you to create a struct to group the components

of an RGB color.

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

!

typedef struct

{

unsigned char red;

unsigned char green;

unsigned char blue;

} Color;

!

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool

{

Color carColor = {255, 160, 0};

NSLog(@"Your paint job is (R: %hhu, G: %hhu, B: %hhu)", carColor.red,

carColor.green, carColor.blue);

}

return 0;

}

Structs](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session2-objective-cbasics-140317160531-phpapp02/85/Session-2-Objective-C-basics-23-320.jpg)

![• The enum keyword is used to create an enumerated type, which is a

collection of related constants.

• Like structs, it’s often convenient to typedef enumerated types with a

descriptive name:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

!

typedef struct

{

unsigned char red;

unsigned char green;

unsigned char blue;

} Color;

!

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool

{

Color carColor = {255, 160, 0};

NSLog(@"Your paint job is (R: %hhu, G: %hhu, B: %hhu)", carColor.red,

carColor.green, carColor.blue);

}

return 0;

}

Enums](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session2-objective-cbasics-140317160531-phpapp02/85/Session-2-Objective-C-basics-24-320.jpg)

![#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

!

typedef enum

{

FORD,

HONDA,

NISSAN,

PORSCHE

} CarModel;

!

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool

{

CarModel myCar = NISSAN;

switch (myCar)

{

case FORD:

case PORSCHE:

NSLog(@"You like Western cars?");

break;

case HONDA:

case NISSAN:

NSLog(@"You like Japanese cars?");

break;

default:

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

Enums](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session2-objective-cbasics-140317160531-phpapp02/85/Session-2-Objective-C-basics-25-320.jpg)

![• Since Objective-C is a superset of C, it has access to the primitive arrays

found in C.

• Generally, the higher-level NSArray and NSMutableArray classes provided by

the Foundation Framework are much more convenient than C arrays;

however, primitive arrays can still prove useful for performance intensive

environments.

• Their syntax is as follows:

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

!

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool

{

int years[4] = {1968, 1970, 1989, 1999};

years[0] = 1967;

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++)

{

NSLog(@"The year at index %d is: %d", i, years[i]);

}

}

return 0;

}

Primitives Arrays](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session2-objective-cbasics-140317160531-phpapp02/85/Session-2-Objective-C-basics-36-320.jpg)

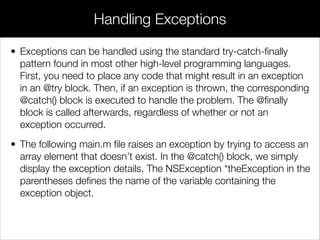

![#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

!

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool

{

NSArray *inventory = @[@"Honda Civic",

@"Nissan Versa",

@"Ford F-150"];

int selectedIndex = 3;

@try

{

NSString *car = inventory[selectedIndex];

NSLog(@"The selected car is: %@", car);

}

@catch(NSException *theException)

{

NSLog(@"An exception occurred: %@", theException.name);

NSLog(@"Here are some details: %@", theException.reason);

}

@finally

{

NSLog(@"Executing finally block");

}

}

return 0;

}

Handling Exceptions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session2-objective-cbasics-140317160531-phpapp02/85/Session-2-Objective-C-basics-42-320.jpg)