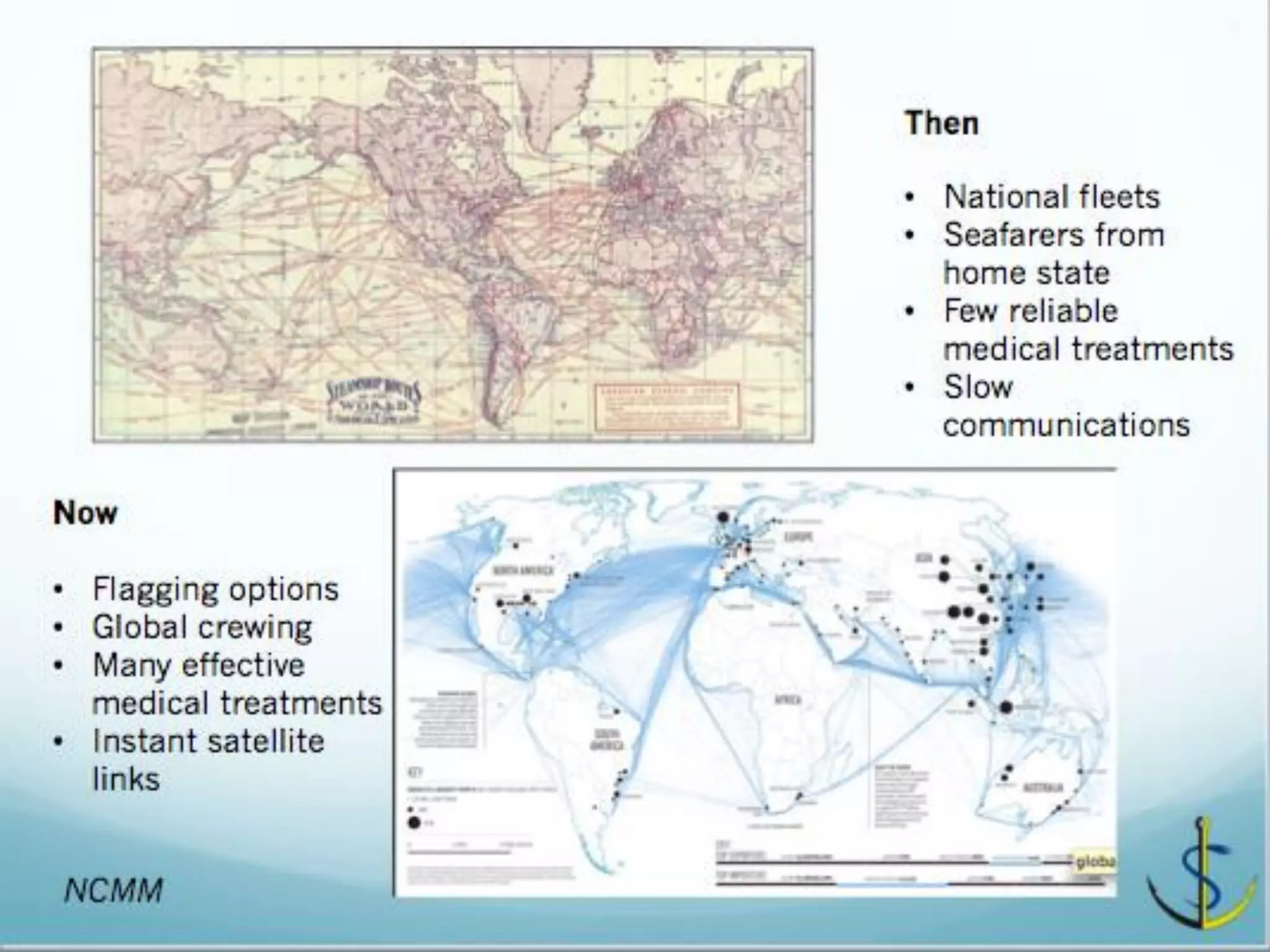

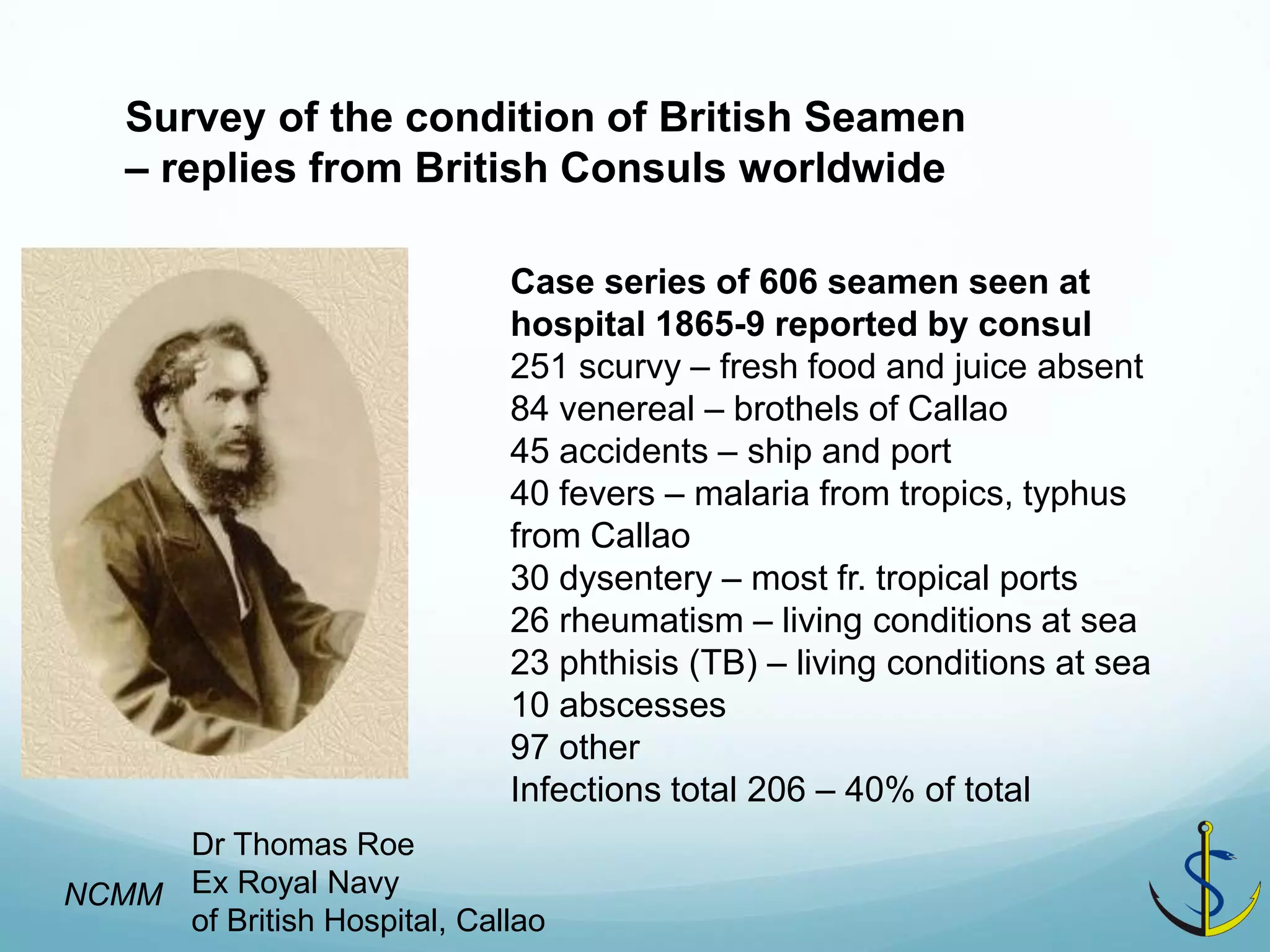

This document discusses why maritime health is an international issue rather than just a national responsibility. While ships used to operate within single countries, globalization has made fleets multinational with crews from different countries. This poses challenges for applying health standards consistently when countries regulate maritime health differently. The document examines historical examples like health issues for seamen in 19th century Callao, Peru to show how health problems have long transcended national boundaries in the shipping industry. It argues that principles now exist for international cooperation on maritime health management, but vested interests of different groups pose barriers to realizing a unified approach.

![A changing world 1

[UK Seafarer Mortality 1925- 2005] Infection and respiratory down by 1955.

-Immunisation

-Precautions

-Antibiotics

Circulatory up and slow fall

- Lifestyle and age, worse prognosis at sea. - radiomedical not enough

Sources of risk?

Place of illness?

NCMM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session1-1-timcarter-nshc2014keynotered-140905042741-phpapp02/75/Session-1-1-tim-carter-nshc-2014-keynote-red-12-2048.jpg)