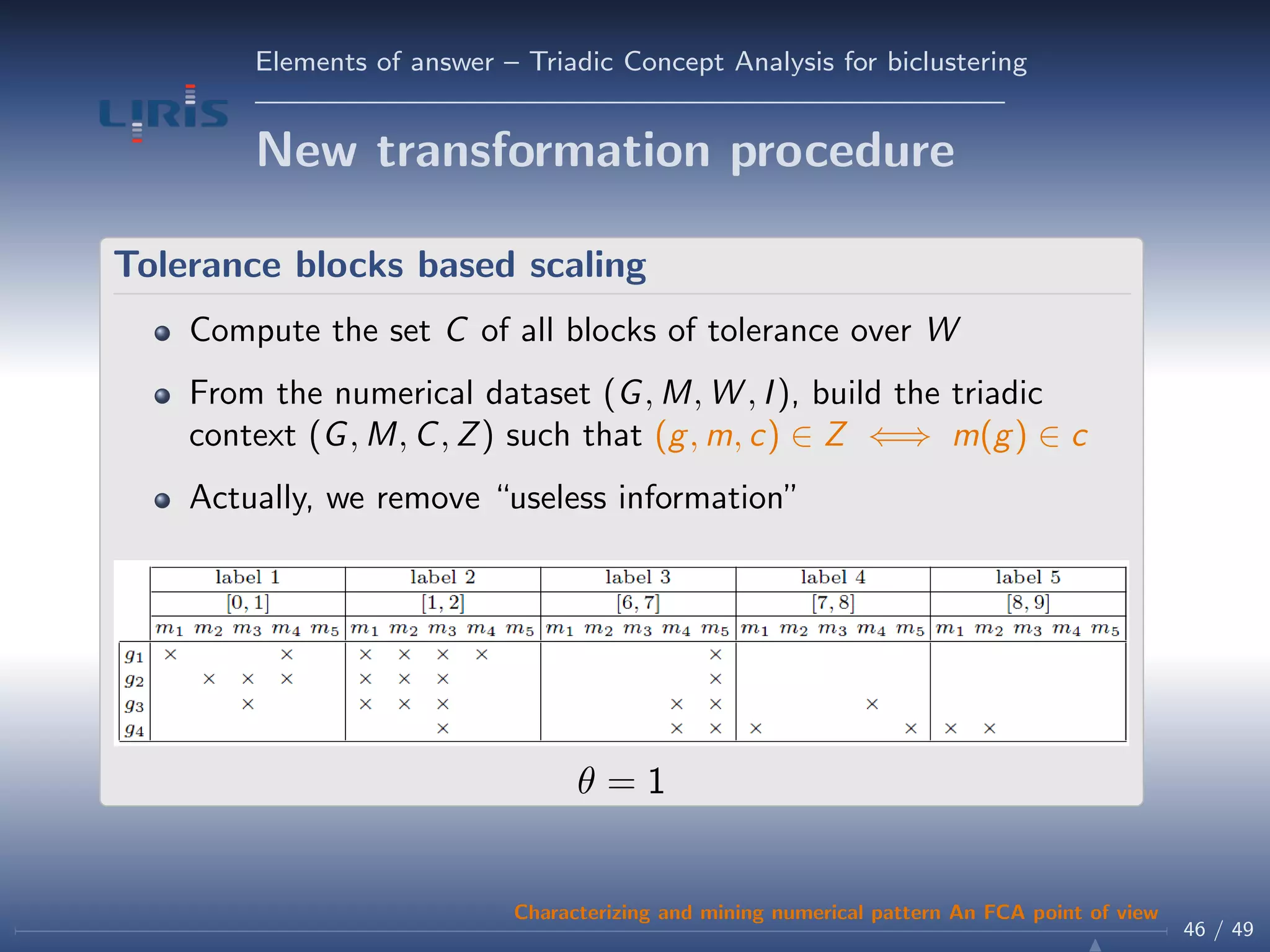

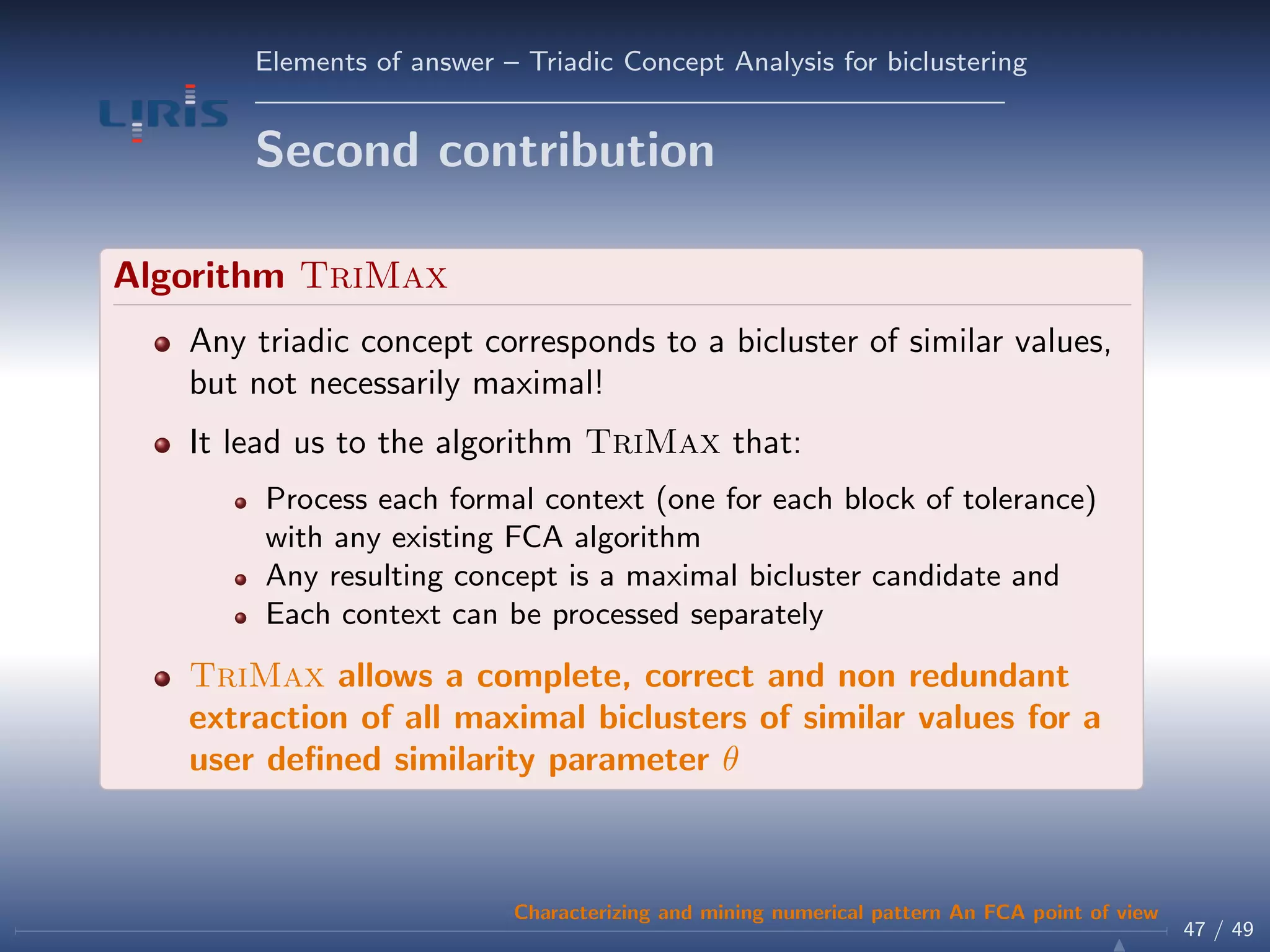

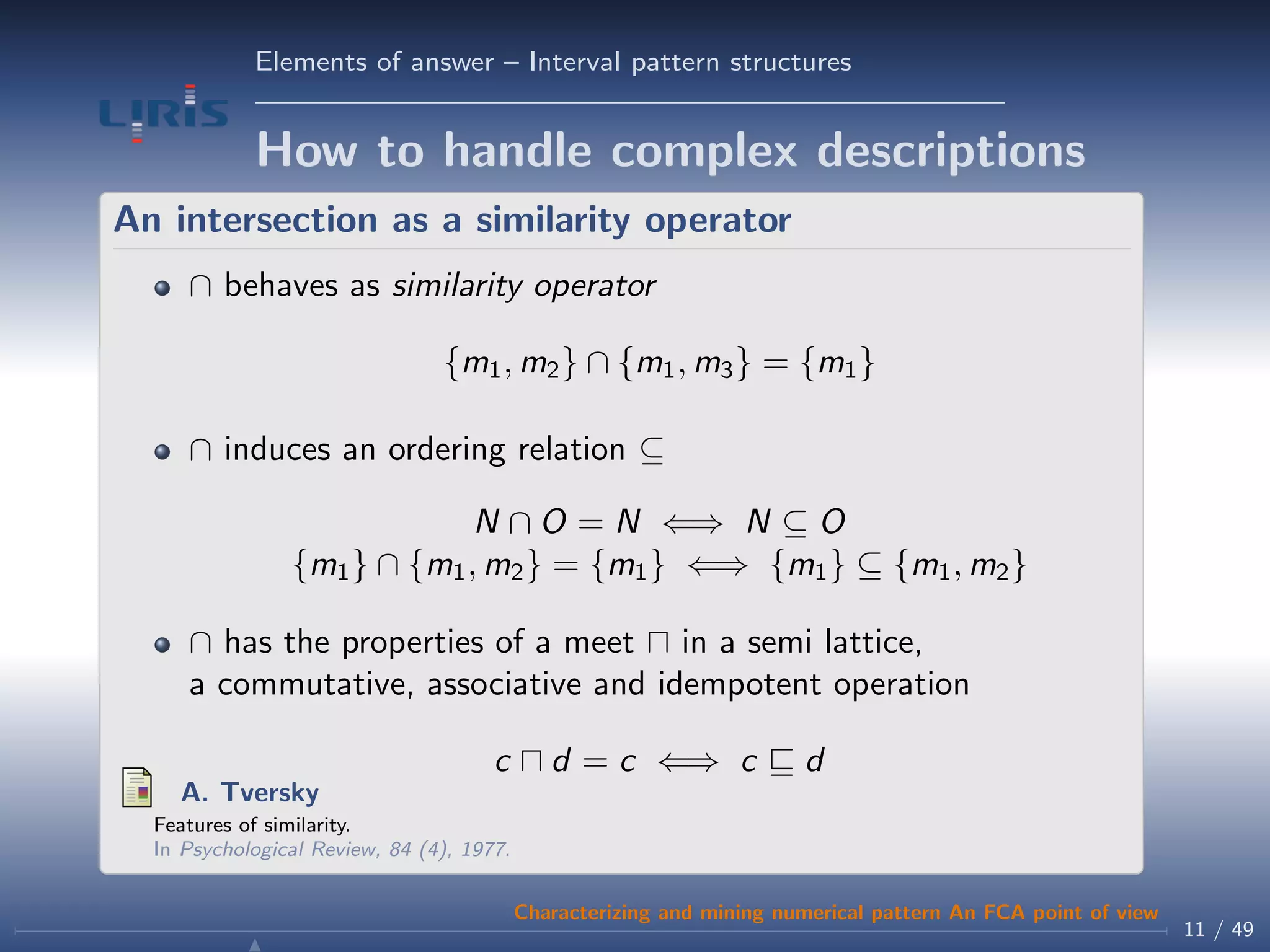

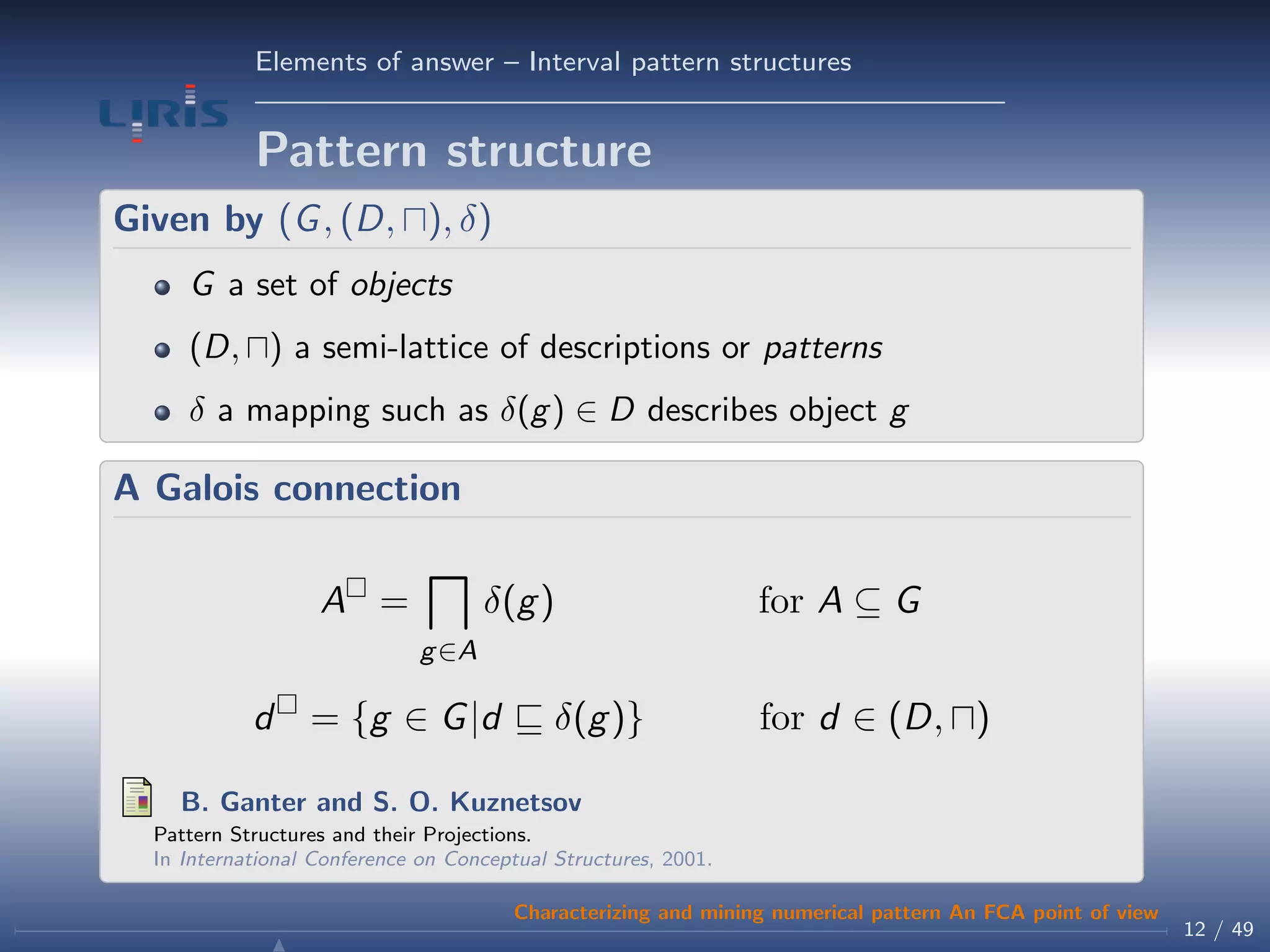

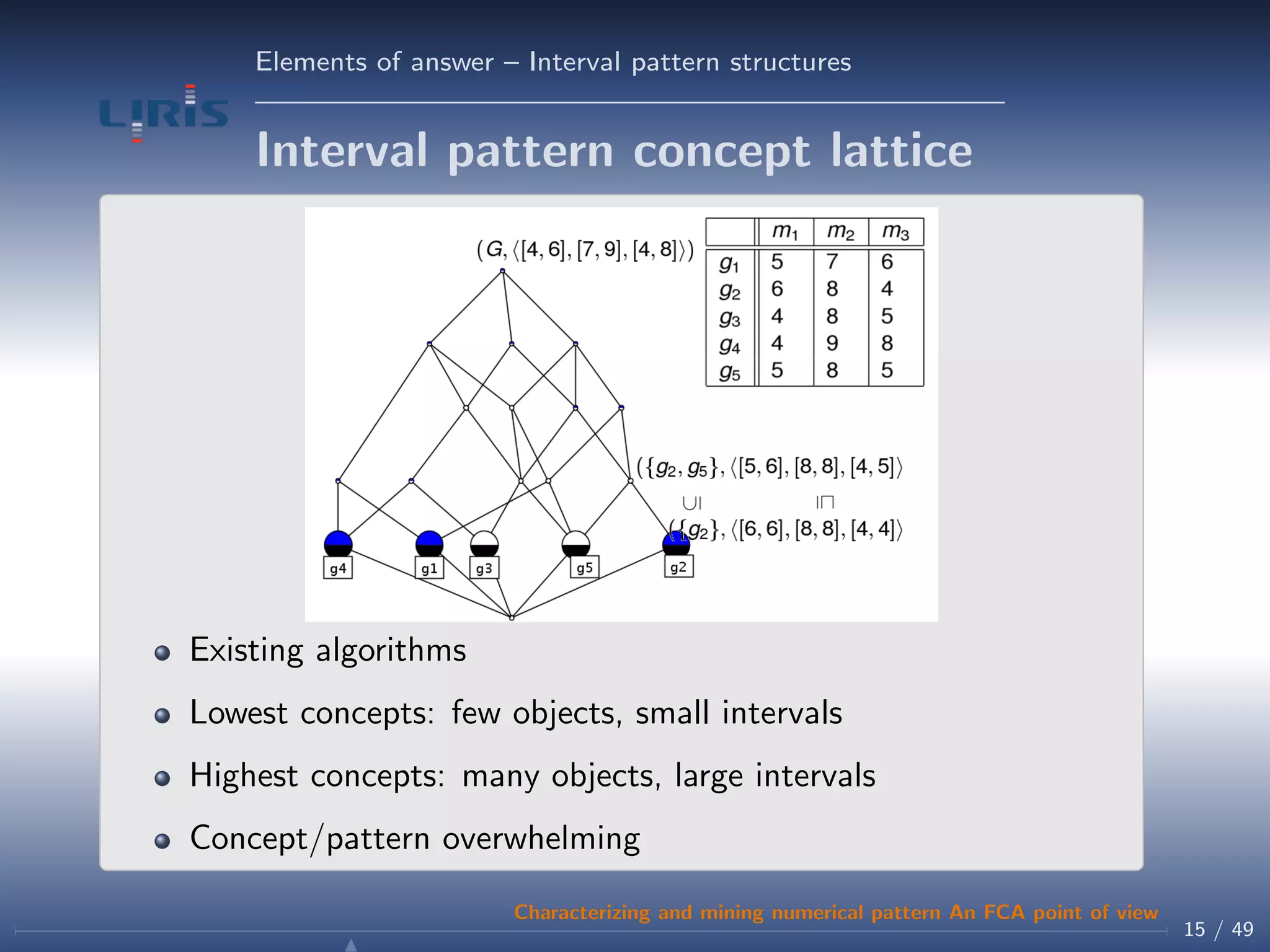

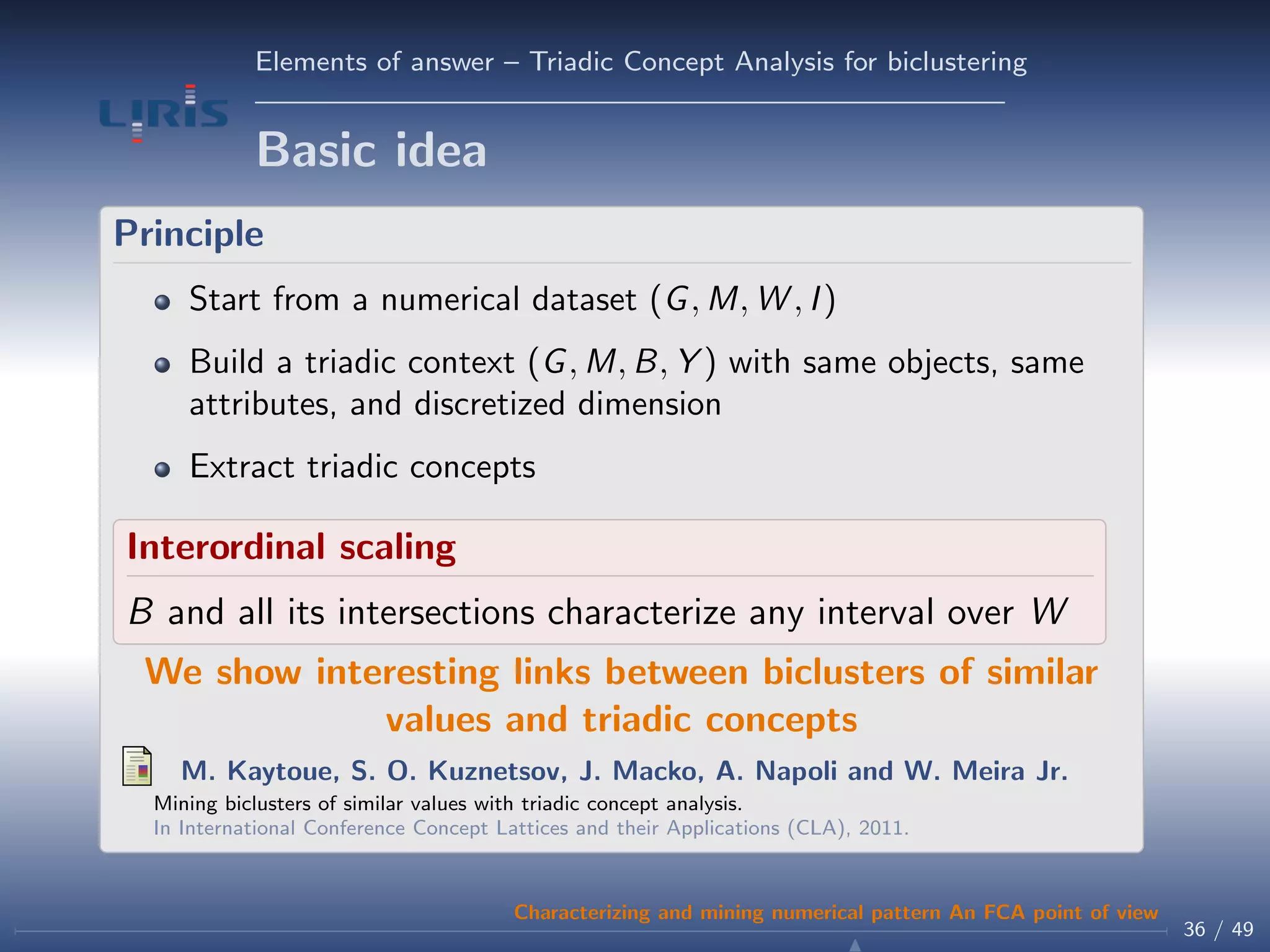

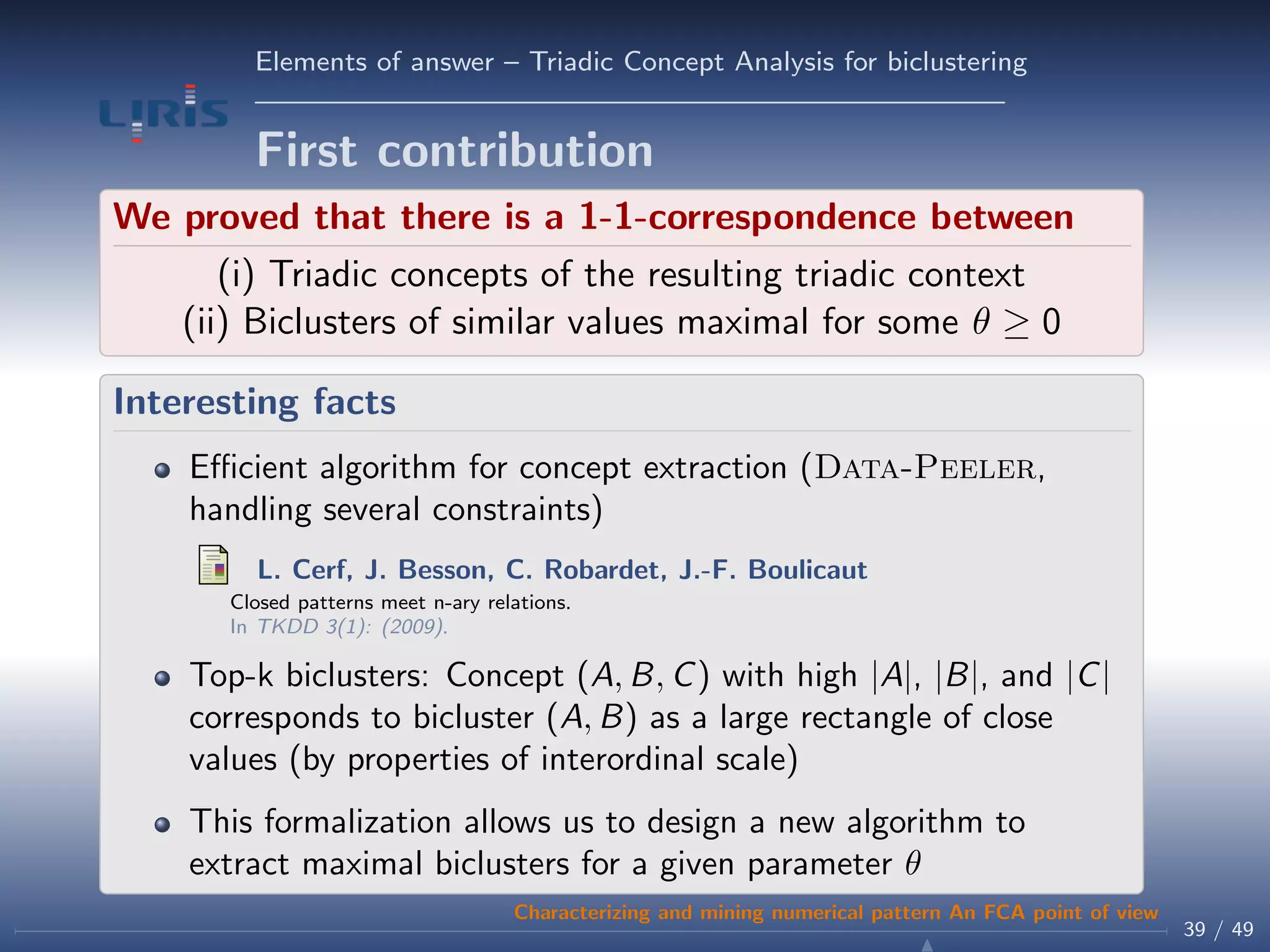

The document discusses characterizing and mining numerical patterns through the lens of Formal Concept Analysis (FCA). It introduces concepts such as interval pattern structures, similarity relations, and biclustering while addressing the extraction of meaningful numerical patterns from data. The research emphasizes the application of FCA methodologies for efficient data analysis and pattern representation.

![Elements of answer – Interval pattern structures

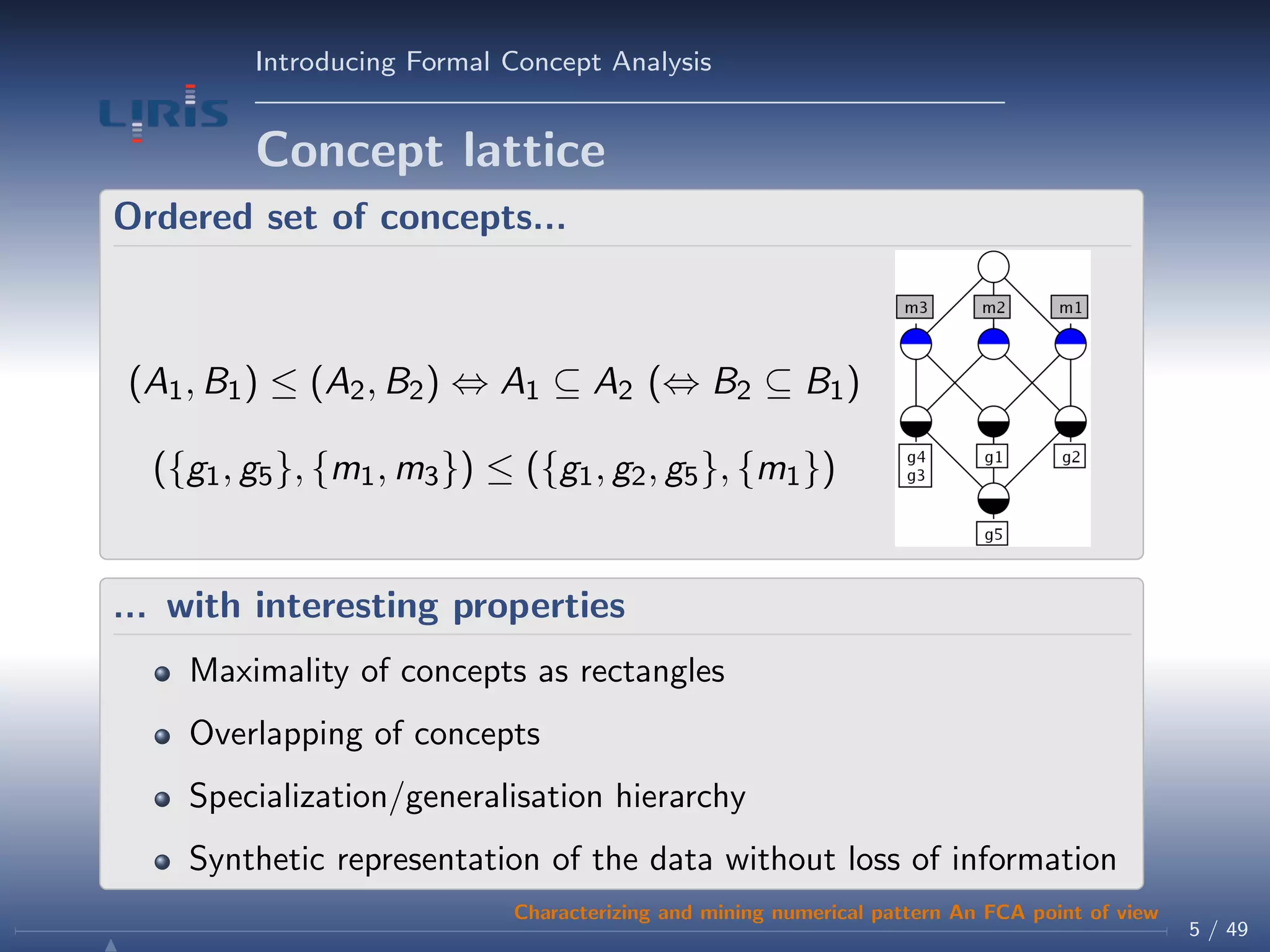

Ordering descriptions in numerical data

(D, ) as a meet-semi-lattice with as a “convexification”

m1 m2 m3

g1 5 7 6

g2 6 8 4

g3 4 8 5

g4 4 9 8

g5 5 8 5

4 5 6

[4,5] [5,6]

[4,6]

13 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-13-2048.jpg)

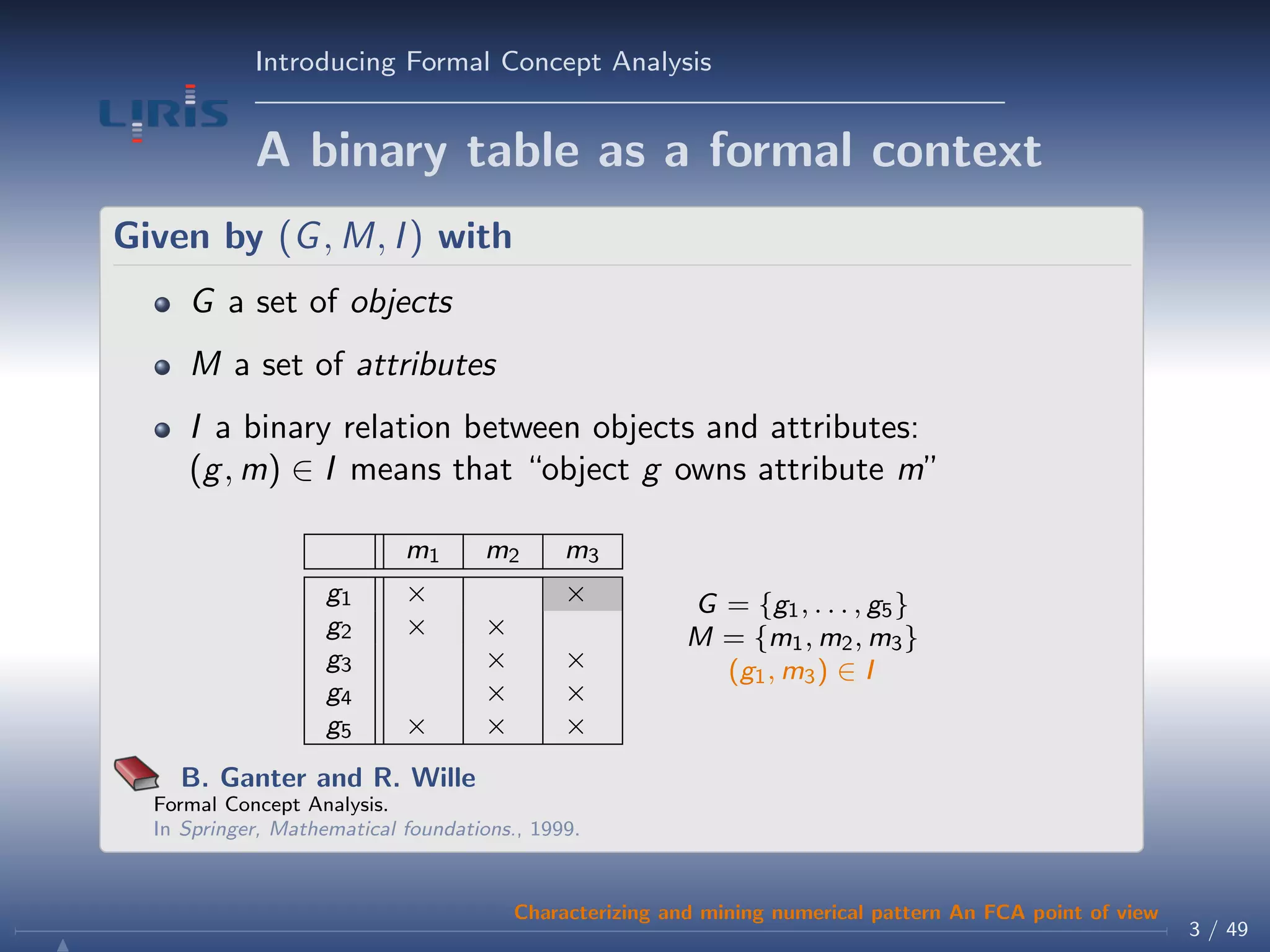

![Elements of answer – Interval pattern structures

Numerical data are pattern structures

Interval pattern structures

m1 m2 m3

g1 5 7 6

g2 6 8 4

g3 4 8 5

g4 4 9 8

g5 5 8 5

{g1, g2} =

g∈{g1,g2}

δ(g)

= 5, 7, 6 6, 8, 4

= [5, 6], [7, 8], [4, 6]

[5, 6], [7, 8], [4, 6] = {g ∈ G| [5, 6], [7, 8], [4, 6] δ(g)}

= {g1, g2, g5}

({g1, g2, g5}, [5, 6], [7, 8], [4, 6] ) is a (pattern) concept

14 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-14-2048.jpg)

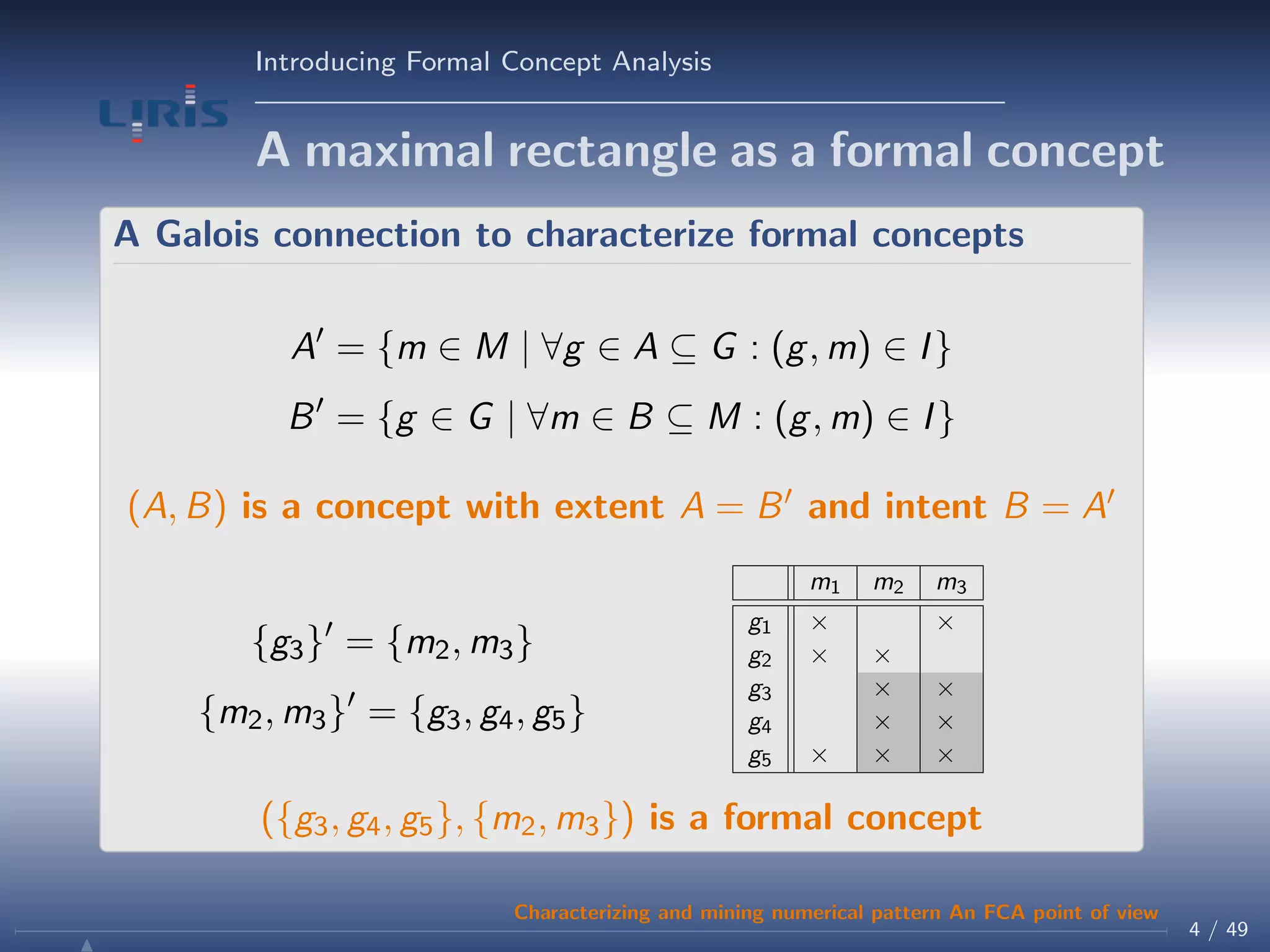

![Elements of answer – Interval pattern structures

Links with conceptual scaling

Interordinal scaling [Ganter & Wille]

A scale to encode intervals of attribute values

m1 ≤ 4 m1 ≤ 5 m1 ≤ 6 m1 ≥ 4 m1 ≥ 5 m1 ≥ 6

4 × × × ×

5 × × × ×

6 × × × ×

Equivalent concept lattice

({g1, g2, g5}, {m1 ≤ 6, m1 ≥ 4, m1 ≥ 5, ... , ... })

({g1, g2, g5}, [5, 6] , ... , ... )

Why should we use pattern structures as we have scaling?

Processing a pattern structure is more efficient

M. Kaytoue, S. O. Kuznetsov, A. Napoli and S. Duplessis

Mining Gene Expression Data with Pattern Structures in Formal Concept Analysis.

In Information Sciences. Spec. Iss.: Lattices (Elsevier), 181(10): 1989-2001 (2011).

16 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-16-2048.jpg)

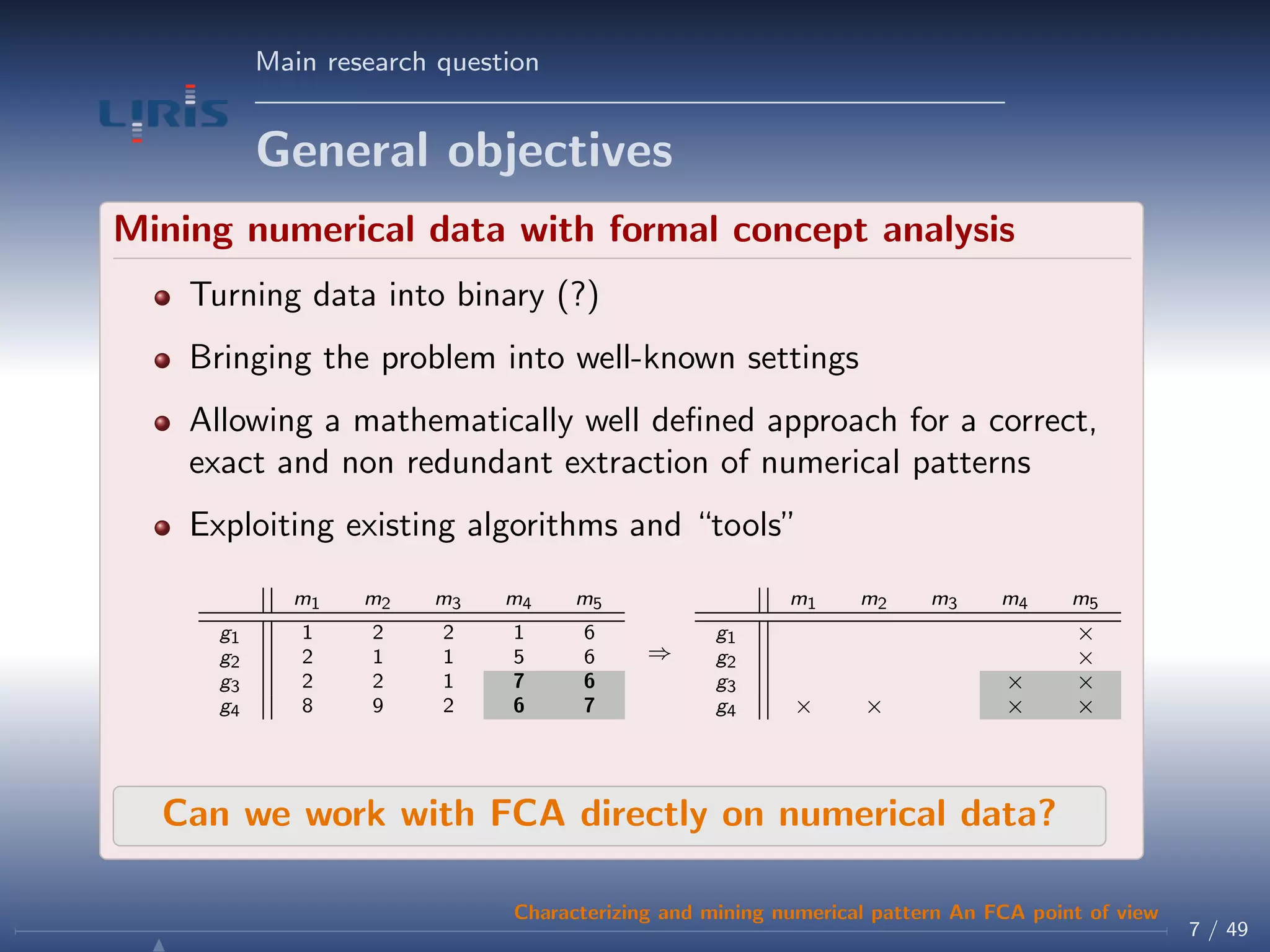

![Elements of answer – Towards condensed representations

Interval pattern search space

Counting all possible interval patterns

[am1 , bm1 ], [am2 , bm2 ], ...

where ami , bmi ∈ Wmi

m1 m2 m3

g1 5 7 6

g2 6 8 4

g3 4 8 5

g4 4 9 8

g5 5 8 5

i∈{1,...,|M|}

|Wmi | × (|Wmi | + 1)

2

360 possible interval patterns in our small example

M. Kaytoue, S. O. Kuznetsov, and A. Napoli

Revisiting Numerical Pattern Mining with Formal Concept Analysis.

In International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), 2011.

18 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-18-2048.jpg)

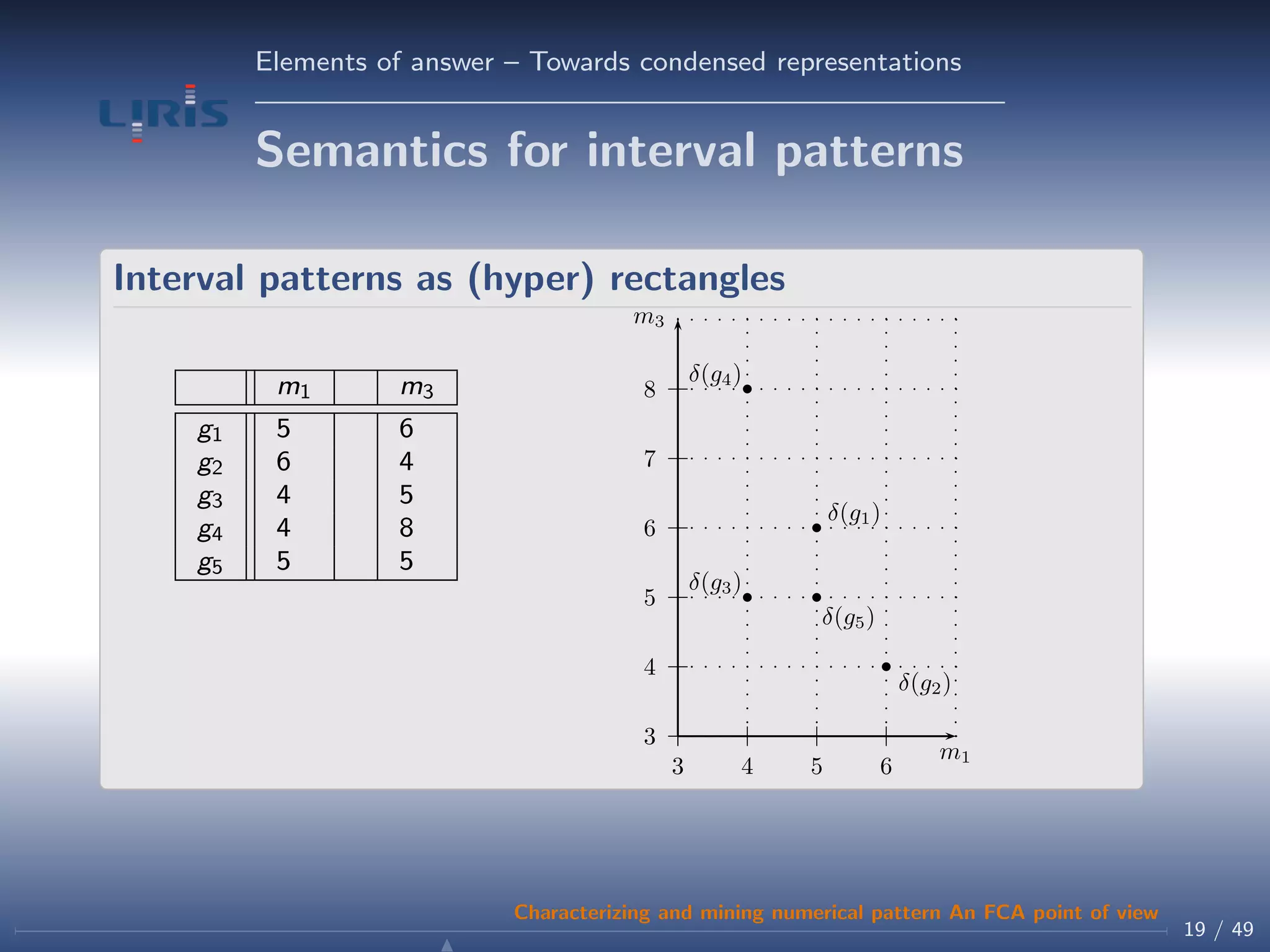

![Elements of answer – Towards condensed representations

Semantics for interval patterns

Interval patterns as (hyper) rectangles

m1 m3

g1 5 6

g2 6 4

g3 4 5

g4 4 8

g5 5 5

[4, 5], [5, 6] = {g1, g3, g5}

3

4

5

6

7

8

3 4 5 6

m1

m3

δ(g1)

δ(g2)

δ(g3)

δ(g4)

δ(g5)

19 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-20-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Towards condensed representations

Semantics for interval patterns

Interval patterns as (hyper) rectangles

m1 m3

g1 5 6

g2 6 4

g3 4 5

g4 4 8

g5 5 5

[4, 5], [5, 6] = {g1, g3, g5}

[4, 5], [4, 6] = {g1, g3, g5}

3

4

5

6

7

8

3 4 5 6

m1

m3

δ(g1)

δ(g2)

δ(g3)

δ(g4)

δ(g5)

19 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-21-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Towards condensed representations

Semantics for interval patterns

Interval patterns as (hyper) rectangles

m1 m3

g1 5 6

g2 6 4

g3 4 5

g4 4 8

g5 5 5

[4, 5], [5, 6] = {g1, g3, g5}

[4, 5], [4, 6] = {g1, g3, g5}

[4, 6], [5, 6] = {g1, g3, g5} 3

4

5

6

7

8

3 4 5 6

m1

m3

δ(g1)

δ(g2)

δ(g3)

δ(g4)

δ(g5)

19 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-22-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Towards condensed representations

A condensed representation

Equivalence classes of interval patterns

Two interval patterns with same image are said to be equivalent

c ∼= d ⇐⇒ c = d

Equivalence class of a pattern d

[d] = {c|c ∼= d}

with a unique closed pattern: the smallest rectangle

and one or several generators: the largest rectangles

Y. Bastide, R. Taouil, N. Pasquier, G. Stumme, and L. Lakhal.

Mining frequent patterns with counting inference.

SIGKDD Expl., 2(2):66–75, 2000.

In our example: 360 patterns ; 18 closed ; 44 generators

20 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-23-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Towards condensed representations

A condensed representation

Remarks

4 5 6

[4,5] [5,6]

[4,6]

Compression rate varies between 107

and 109

Interordinal scaling: encodes 30.000 binary patterns

not efficient even with best algorithms (e.g. LCMv2)

redundancy problem discarding its use for generator extraction

MDL, quantitative association rule mining, k-anonymisation

Need of fault-tolerant condensed representations

21 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-24-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Introducing a similarity relation

Grouping in a same concept objects having similar values?

A natural similarity relation on numbers

a θ b ⇔ |a − b| ≤ θ e.g. 4 1 5 4 1 6

Similarity operator in pattern structures

4 5 6

[4,5] [5,6]

[4,6]

How to consider a similarity relation w.r.t. a distance?

23 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-26-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Introducing a similarity relation

Grouping in a same concept objects having similar values?

A natural similarity relation on numbers

a θ b ⇔ |a − b| ≤ θ e.g. 4 1 5 4 1 6

Similarity operator in pattern structures

θ = 2

4 5 6

[4,5] [5,6]

[4,6]

How to consider a similarity relation w.r.t. a distance?

23 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-27-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Introducing a similarity relation

Grouping in a same concept objects having similar values?

A natural similarity relation on numbers

a θ b ⇔ |a − b| ≤ θ e.g. 4 1 5 4 1 6

Similarity operator in pattern structures

θ = 1

4 5 6

[4,5] [5,6]

[4,6]

How to consider a similarity relation w.r.t. a distance?

23 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-28-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Introducing a similarity relation

Grouping in a same concept objects having similar values?

A natural similarity relation on numbers

a θ b ⇔ |a − b| ≤ θ e.g. 4 1 5 4 1 6

Similarity operator in pattern structures

θ = 04 5 6

[4,5] [5,6]

[4,6]

How to consider a similarity relation w.r.t. a distance?

23 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-29-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Towards a similarity between values

Introduce an element ∗ ∈ (D, ) denoting dissimilarity

c d = ∗ iff c θ d

c d = ∗ iff c θ d

Example with θ = 1

m1 m2 m3

g1 5 7 6

g2 6 8 4

g3 4 8 5

g4 4 9 8

g5 5 8 5

{g3, g4} = [4, 4], [8, 9], ∗

[4, 4], [8, 9], ∗ = {g3, g4}

({g3, g4}, [4, 4], [8, 9], ∗ ) is a pattern concept:

g3 and g4 have similar values for attributes m1 and m2 only

24 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-30-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Towards a similarity between values

Introduce an element ∗ ∈ (D, ) denoting dissimilarity

c d = ∗ iff c θ d

c d = ∗ iff c θ d

Example with θ = 1

m1 m2 m3

g1 5 7 6

g2 6 8 4

g3 4 8 5

g4 4 9 8

g5 5 8 5

{g3, g4} = [4, 4], [8, 9], ∗

[4, 4], [8, 9], ∗ = {g3, g4}

({g3, g4}, [4, 4], [8, 9], ∗ ) is a pattern concept:

g3 and g4 have similar values for attributes m1 and m2 only

Is {g3, g4} maximal w.r.t. similarity? We can add g5...

24 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-31-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Classes of tolerance in numerical data

Towards maximal sets of similar values

θ a tolerance relation : reflexive, symmetric, not transitive

Consider an attribute taking values in {6, 8, 11, 16, 17} and θ = 5

8 5 11, 11 5 16 but 8 5 16

A class of tolerance as a maximal set of pairwise similar values

{6, 8, 11} {11, 16} {16, 17}

[6, 11] [11, 16] [16, 17]

S. O. Kuznetsov

Galois Connections in Data Analysis: Contributions from the Soviet Era and Modern Russian Research.

In Formal Concept Analysis, Foundations and Applications, 2005.

25 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-32-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Tolerance in pattern structures

Projecting the pattern structure

Each value is replaced by the interval characterizing its class of

tolerance (if unique)

Each pattern d is projected with a mapping ψ(d) d

(pre-processing)

rod

Example with θ = 1

m1 m2 m3

g1 5 7 6

g2 6 8 4

g3 4 8 5

g4 4 9 8

g5 5 8 5

{g3, g4} = ψ( [4, 4], [8, 9], ∗ )

= [4, 5], [8, 9], ∗

[4, 5], [8, 9], ∗ = {g3, g4, g5}

26 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-33-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Introducing similarity

Similarity and scaling

m1 m2 m3

g1 6 0 [1, 2]

g2 8 4 [2, 5]

g3 11 8 [4, 5]

g4 16 8 [6, 9]

g5 17 12 [7, 10]

5 6 8 11 16 17

6 × × ×

8 × × ×

11 × × × ×

16 × × ×

17 × ×

(m1,11)

(m1,16)

(m1,[6,11])

(m1,[11,16])

(m1,[16,17])

(m2,4)

(m2,8)

(m2,[0,4])

(m2,[4,8])

(m2,[8,12])

(m3,[1,5])

(m3,[4,9])

(m3,[6,10])

(m3,[4,5])

(m3,[6,9])

g1 × × ×

g2 × × × × ×

g3 × × × × × × × × ×

g4 × × × × × × × × ×

g5 × × ×

27 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-34-2048.jpg)

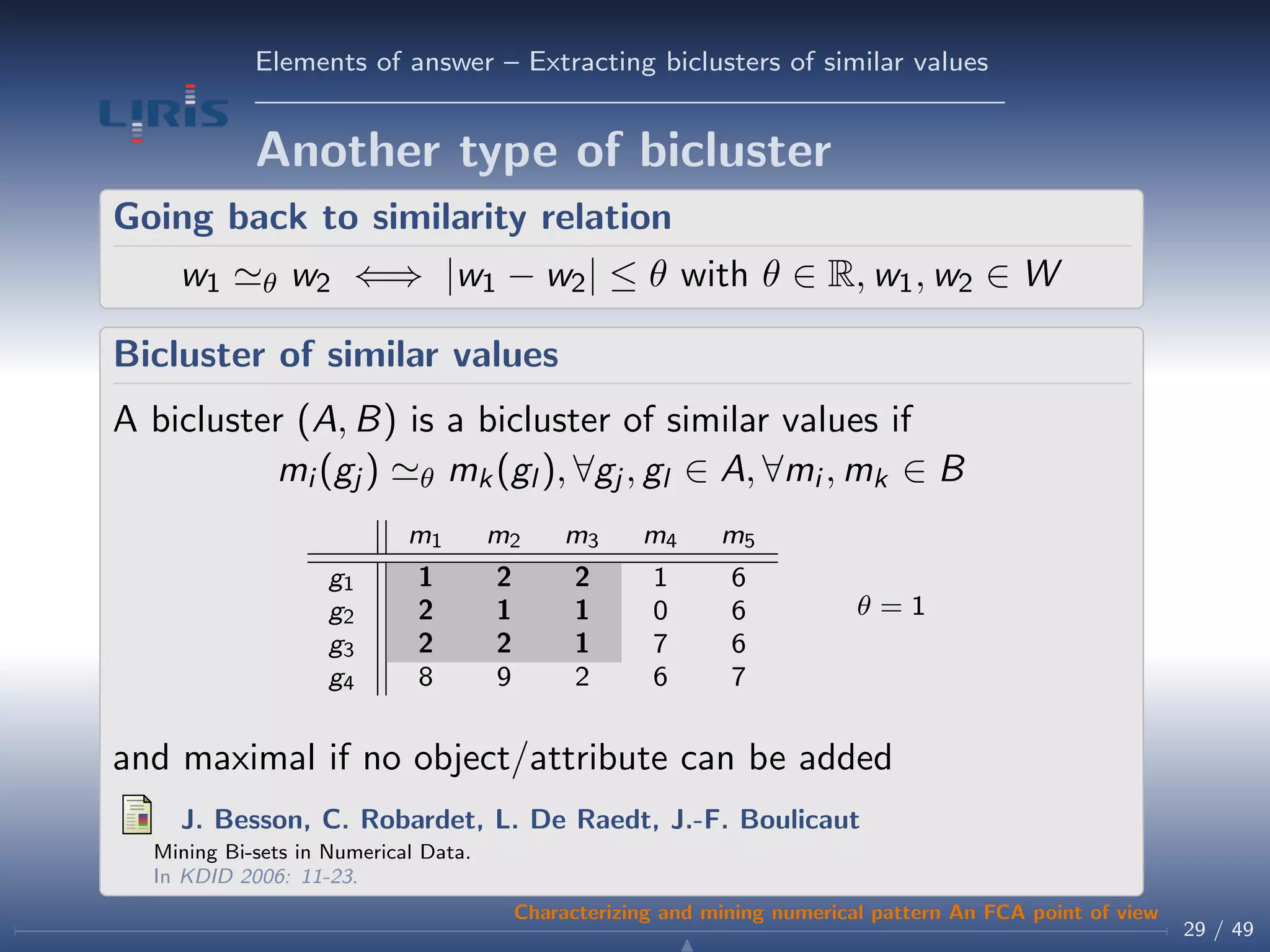

![Elements of answer – Extracting biclusters of similar values

Can we use the interval pattern lattice?

Concept example ({g2, g3}, [2, 2], [1, 2], [1, 1], [0, 7], [6, 6] )

m1 m2 m3 m4 m5

g1 1 2 2 1 6

g2 2 1 1 0 6

g3 2 2 1 7 6

g4 8 9 2 6 7

θ = 1

3 statements to verify

Some intervals have a “size” larger than θ

Some values in two different columns may not be similar

Rectangle may not be maximal

M. Kaytoue, S. O. Kuznetsov, and A. Napoli

Biclustering Numerical Data in Formal Concept Analysis.

In International Conference on Formal Concept Analysis (ICFCA), 2011.

30 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-37-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Extracting biclusters of similar values

First statement

Avoiding intervals with size larger than θ

[a1, b1] [a2, b2] =

[min(a1, a2), max(b1, b2)] if|max(b1, b2) − min(a1, a2)| ≤ θ

∗ otherwise

Going back to our example, with θ = 1

({g2, g3}, [2, 2], [1, 2], [1, 1], ∗, [6, 6] )

m1 m2 m3 m4 m5

g1 1 2 2 1 6

g2 2 1 1 0 6

g3 2 2 1 7 6

g4 8 9 2 6 7

31 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-38-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Extracting biclusters of similar values

Second statement

Values from two columns should be similar

From

({g2, g3}, [2, 2], [1, 2], [1, 1], ∗, [6, 6] )

we group attributes such as their values form a class of tolerance:

m1 m2 m3 m4 m5

g1 1 2 2 1 6

g2 2 1 1 0 6

g3 2 2 1 7 6

g4 8 9 2 6 7

m1 m2 m3 m4 m5

g1 1 2 2 1 6

g2 2 1 1 0 6

g3 2 2 1 7 6

g4 8 9 2 6 7

({g2, g3}, {m1, m2, m3}) ({g2, g3}, {m5})

32 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-39-2048.jpg)

![Elements of answer – Extracting biclusters of similar values

Third statement

Maximal bicluster of similar values

⊥

({g1}, 1, 2, 2, 1,6 ) ({g2}, 2,1,1, 0,6 ) ({g3}, 2,2,1,7,6 ) ({g4}, 8, 9,2,6,7 )

({g1, g2},

[1,2],[1,2],[1,2], [0, 1],6 )

({g1, g3},

[1,2],2,[1,2], ∗,6 )

({g2, g3},

2,[1,2],1, ∗,6

({g3, g4},

∗, ∗, [1,2], [6, 7], [6, 7] )

({g1, g2, g3},

[1, 2], [1, 2], [1, 2], ∗,6 )

({g1, g2, g3, g4},

∗, ∗, [1, 2], ∗, [6, 7] )

Constructing maximal biclusters: bottom-up/top-down

33 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-40-2048.jpg)

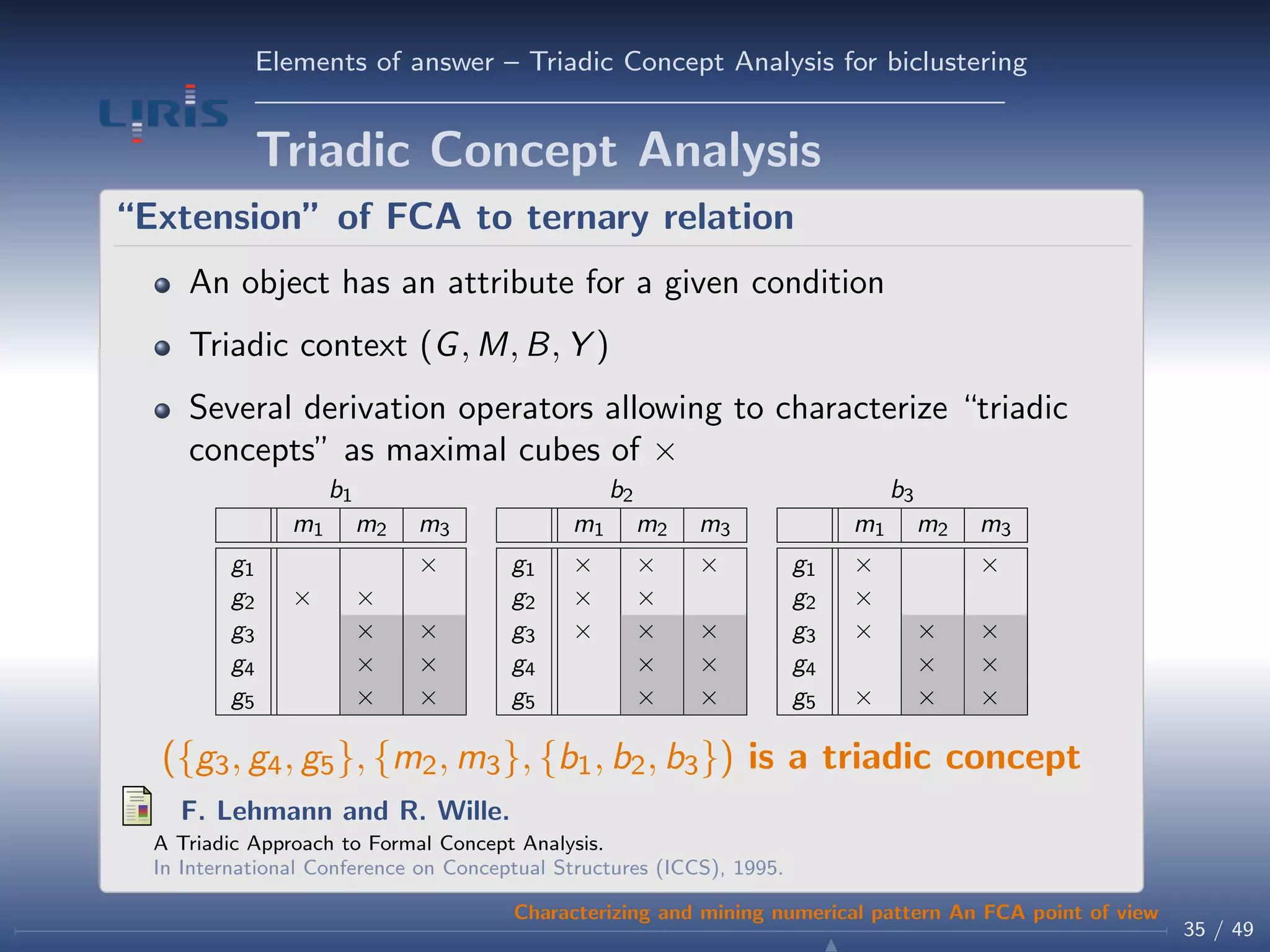

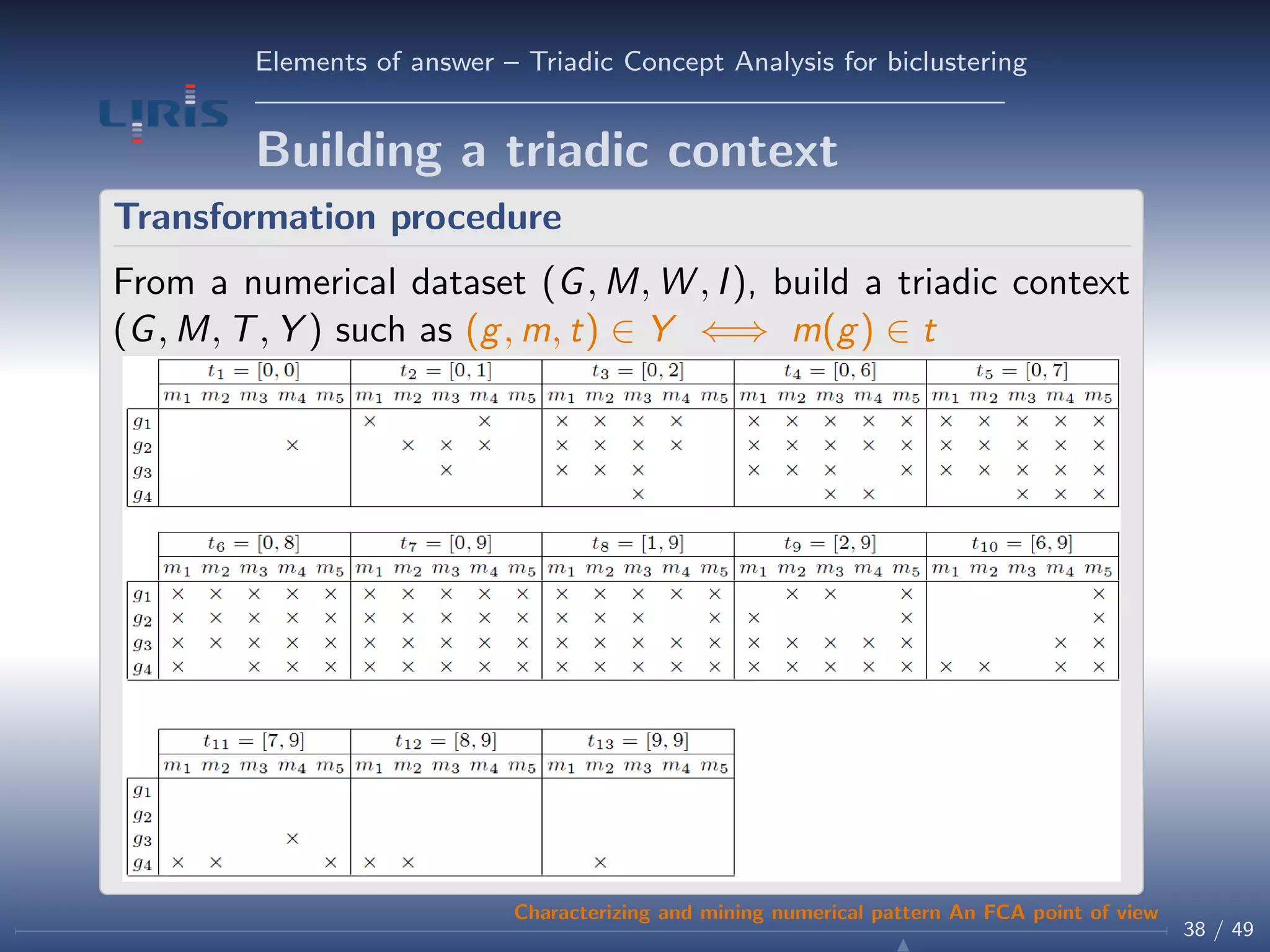

![Elements of answer – Triadic Concept Analysis for biclustering

Discretization method

Interodinal scaling (existing discretization scale)

Let (G, M, W , I) be a numerical dataset (with W the set of

data-values.

Now consider the set

T = {[min(W ), w], ∀w ∈ W } ∪ {[w, max(W )], ∀w ∈ W }.

Known fact: T and all its intersections characterize any interval

of values on W .

Example

With W = {0, 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9}, one has

T = {[0, 0], [0, 1], [0, 2], ..., [0, 9], [1, 9], [2, 9], ..., [9, 9]}

and for example [0, 8] ∩ [2, 9] = [2, 8]

37 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-44-2048.jpg)

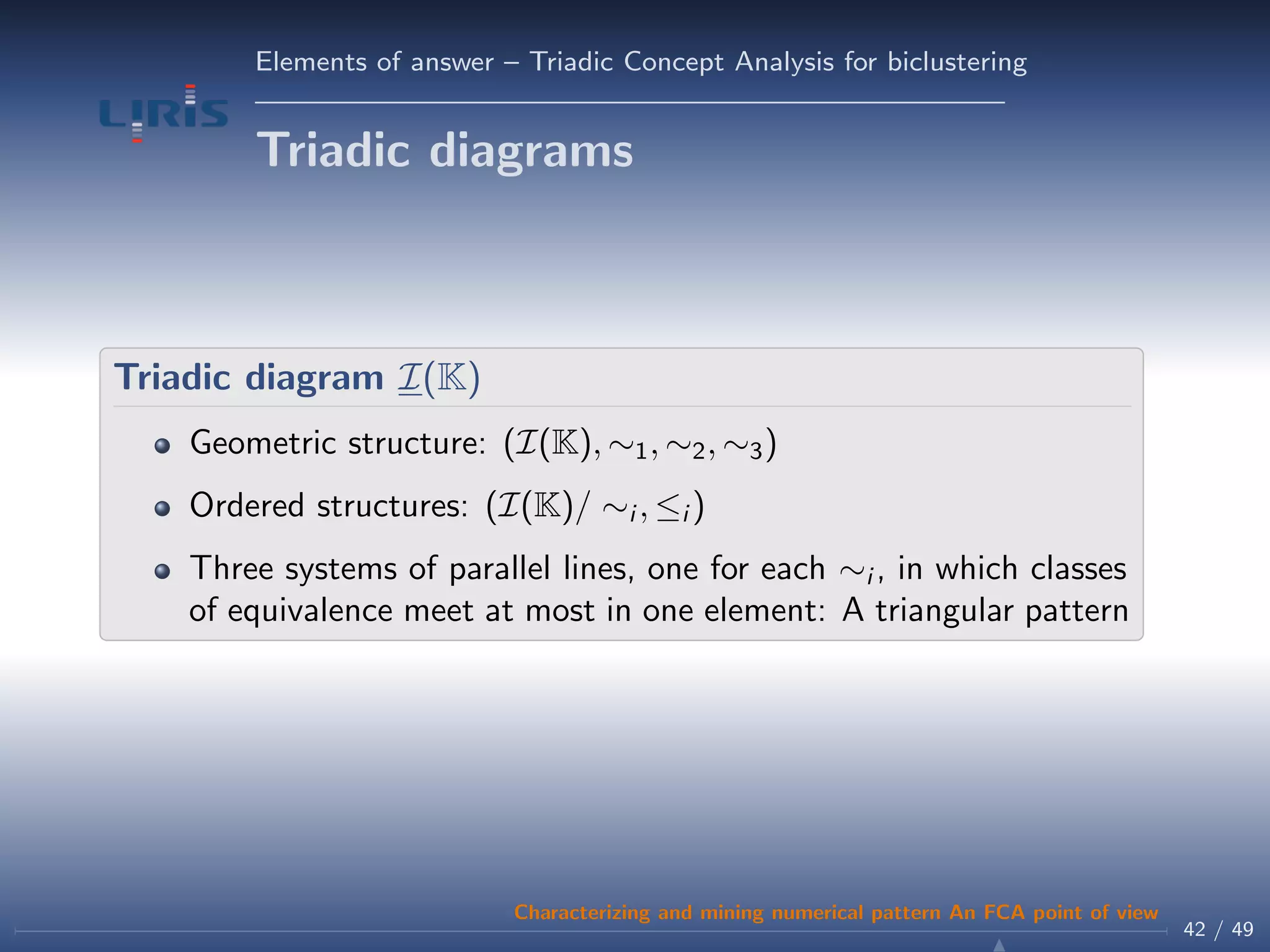

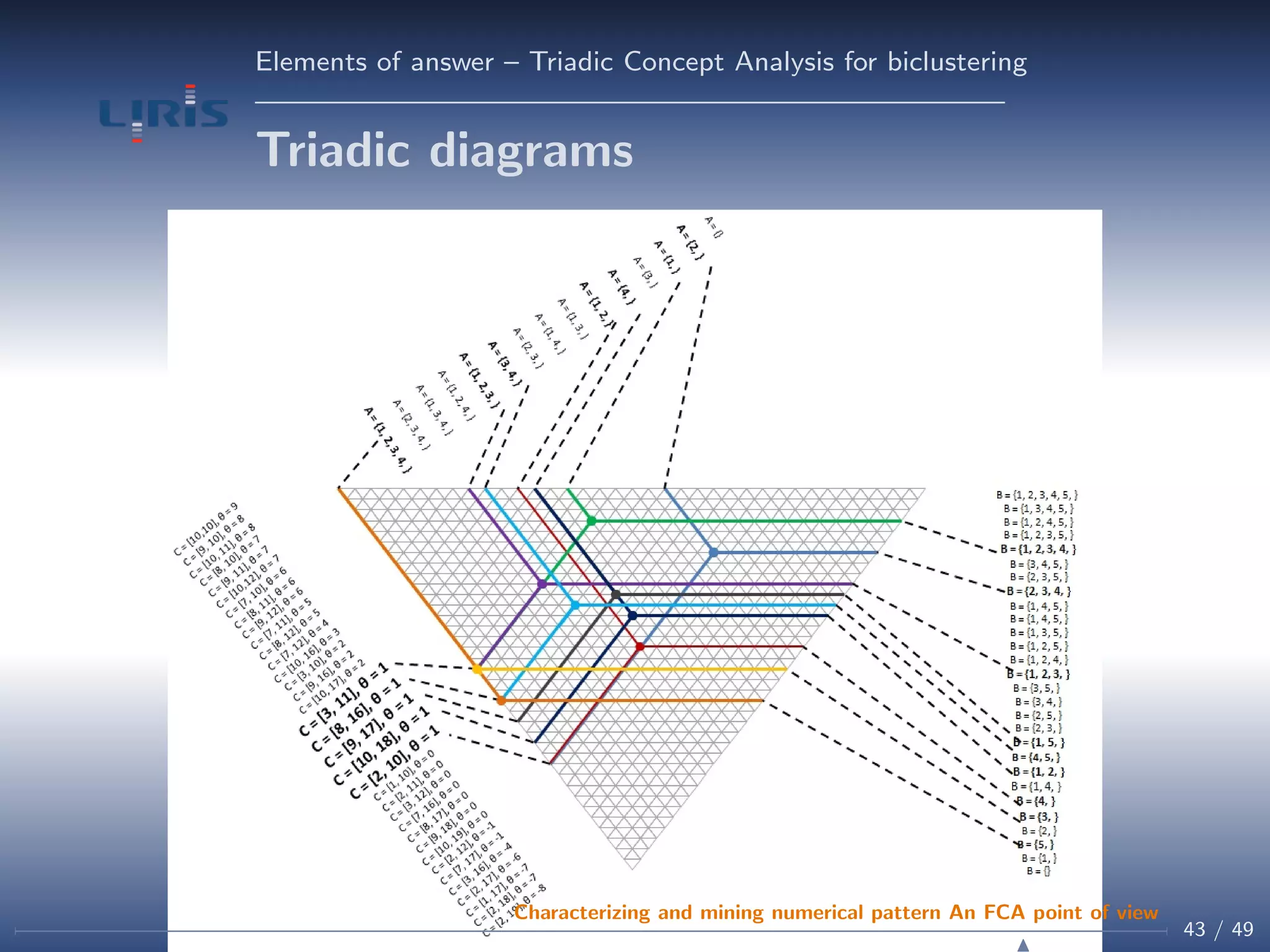

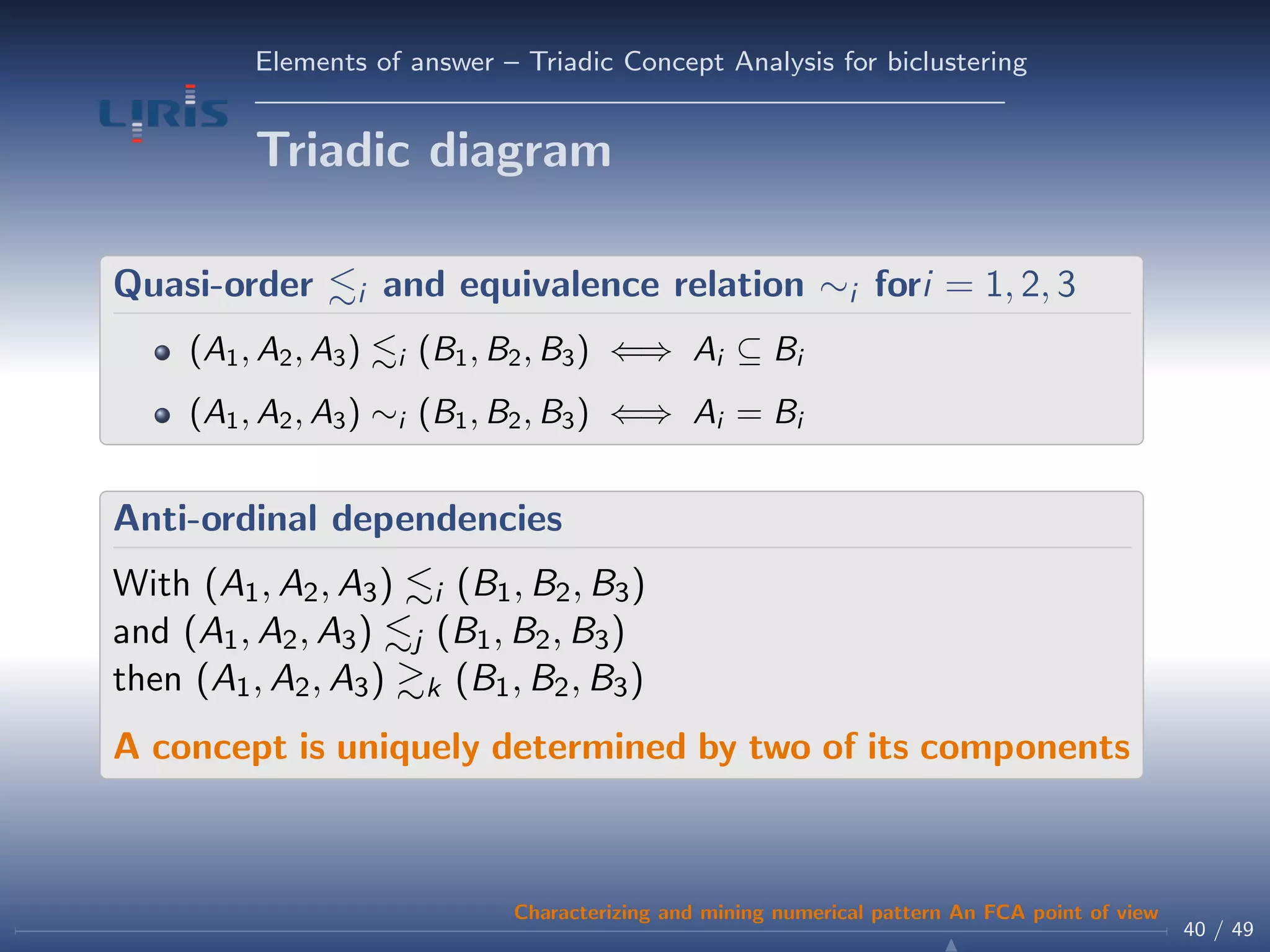

![Elements of answer – Triadic Concept Analysis for biclustering

Triadic diagram

Equivalence and factor sets, i = 1, 2, 3

[(A1, A2, A3)]i is the equivalence class of concepts w.r.t. ∼i

i induces an order ≤i on the factor set I(K)/ ∼i s.t.

[(A1, A2, A3)]i ≤ [(B1, B2, B3)]i ⇐⇒ Ai ⊆ Bi

(I(K)/ ∼i , ≤i ) is the ordered set of all extents

(i=1)/intents(i=2)/modus(i=3) of K

41 / 49

Characterizing and mining numerical pattern An FCA point of view](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/seminar-dag-jun2012-130831073210-phpapp01/75/Characterizing-and-mining-numerical-patterns-an-FCA-point-of-view-48-2048.jpg)