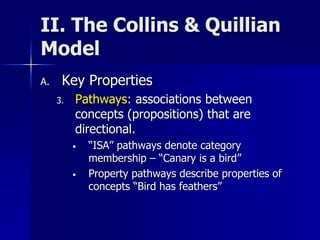

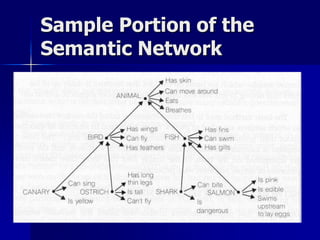

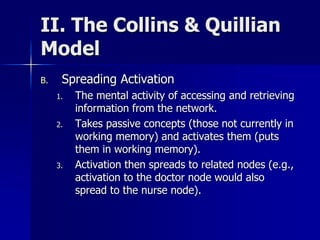

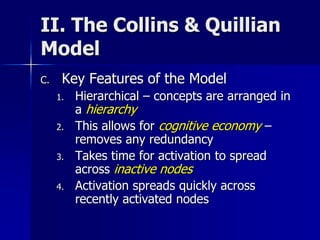

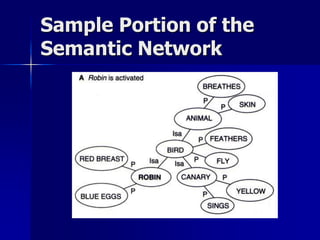

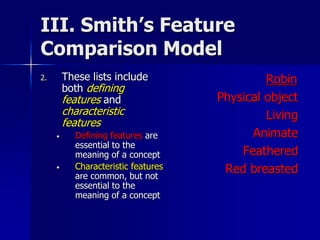

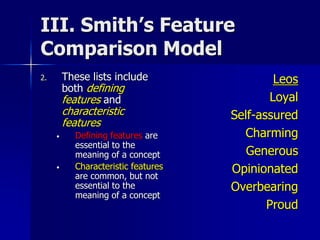

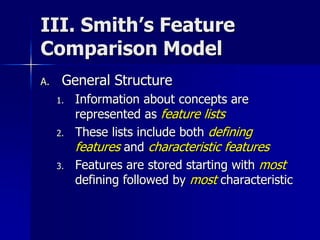

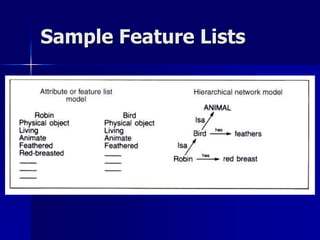

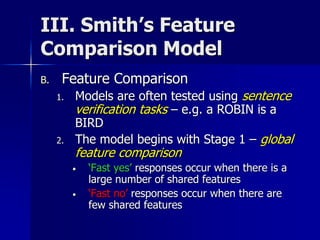

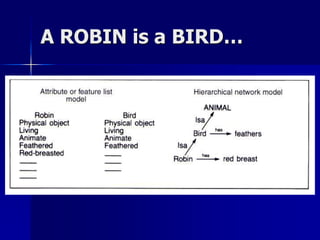

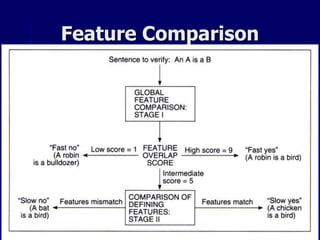

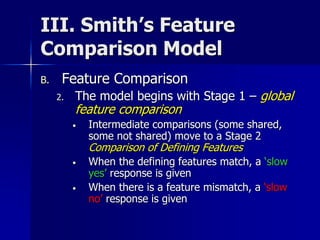

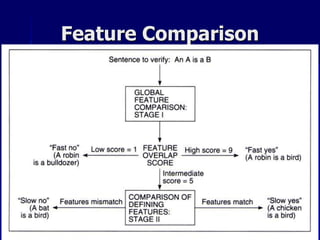

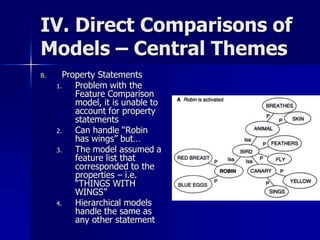

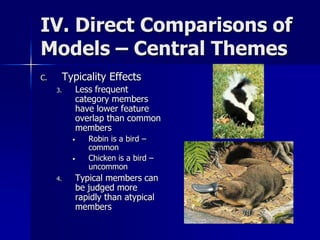

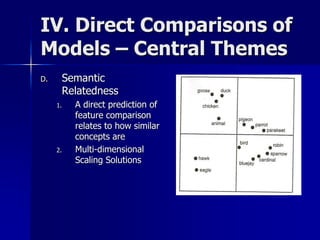

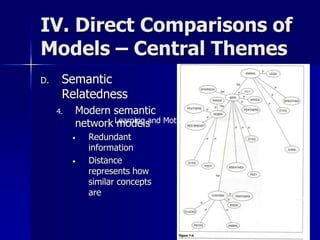

This document discusses different models of semantic memory and conceptual representation. It begins by introducing semantic memory and distinguishing it from episodic memory. It then describes two influential models: the Collins and Quillian hierarchical network model and Smith's feature comparison model. The Collins and Quillian model represents concepts in a hierarchical network and uses spreading activation, while Smith's model represents concepts as lists of defining and characteristic features and performs feature comparisons. The document concludes by comparing the models and discussing topics like typicality effects and semantic relatedness.