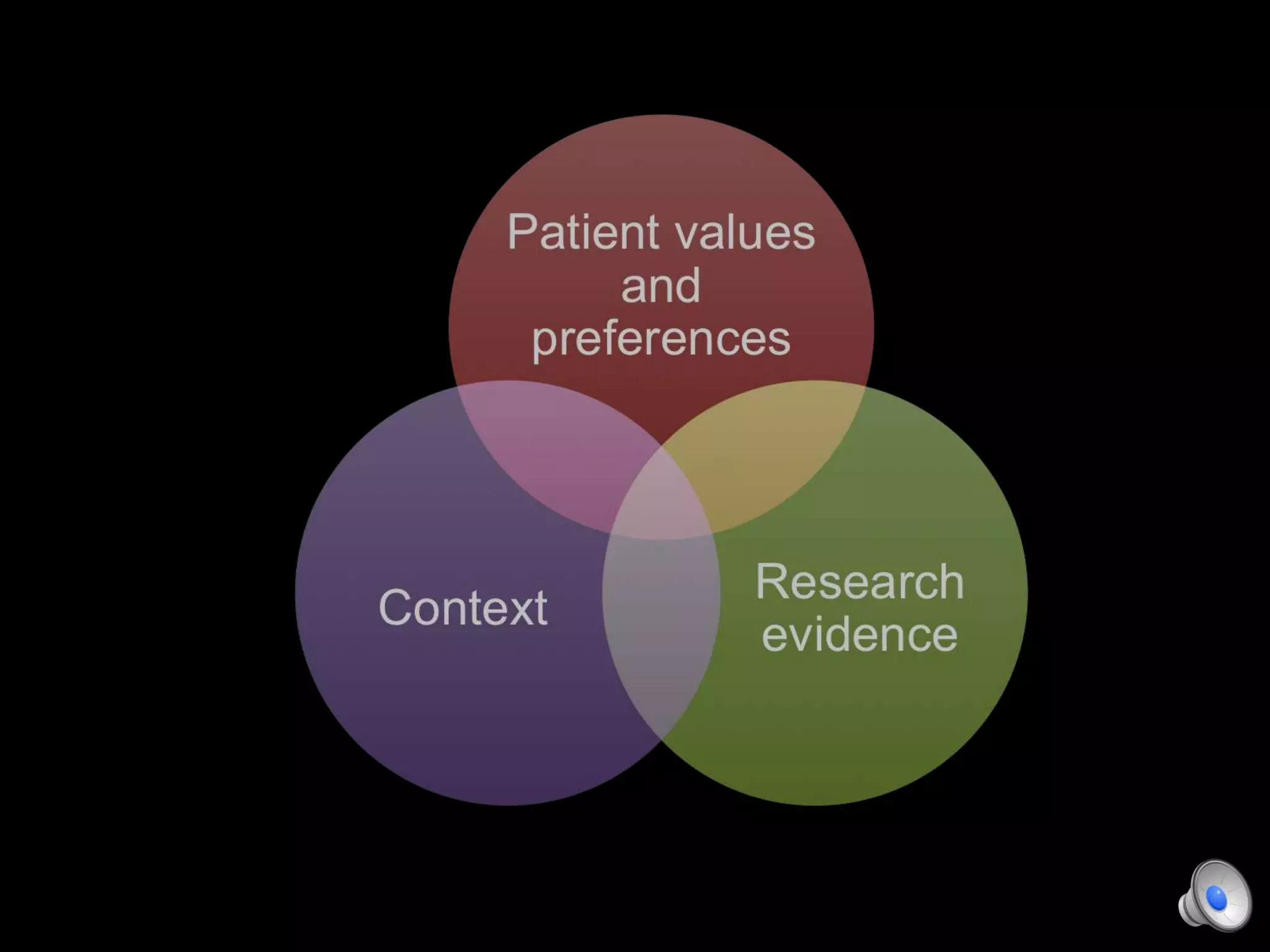

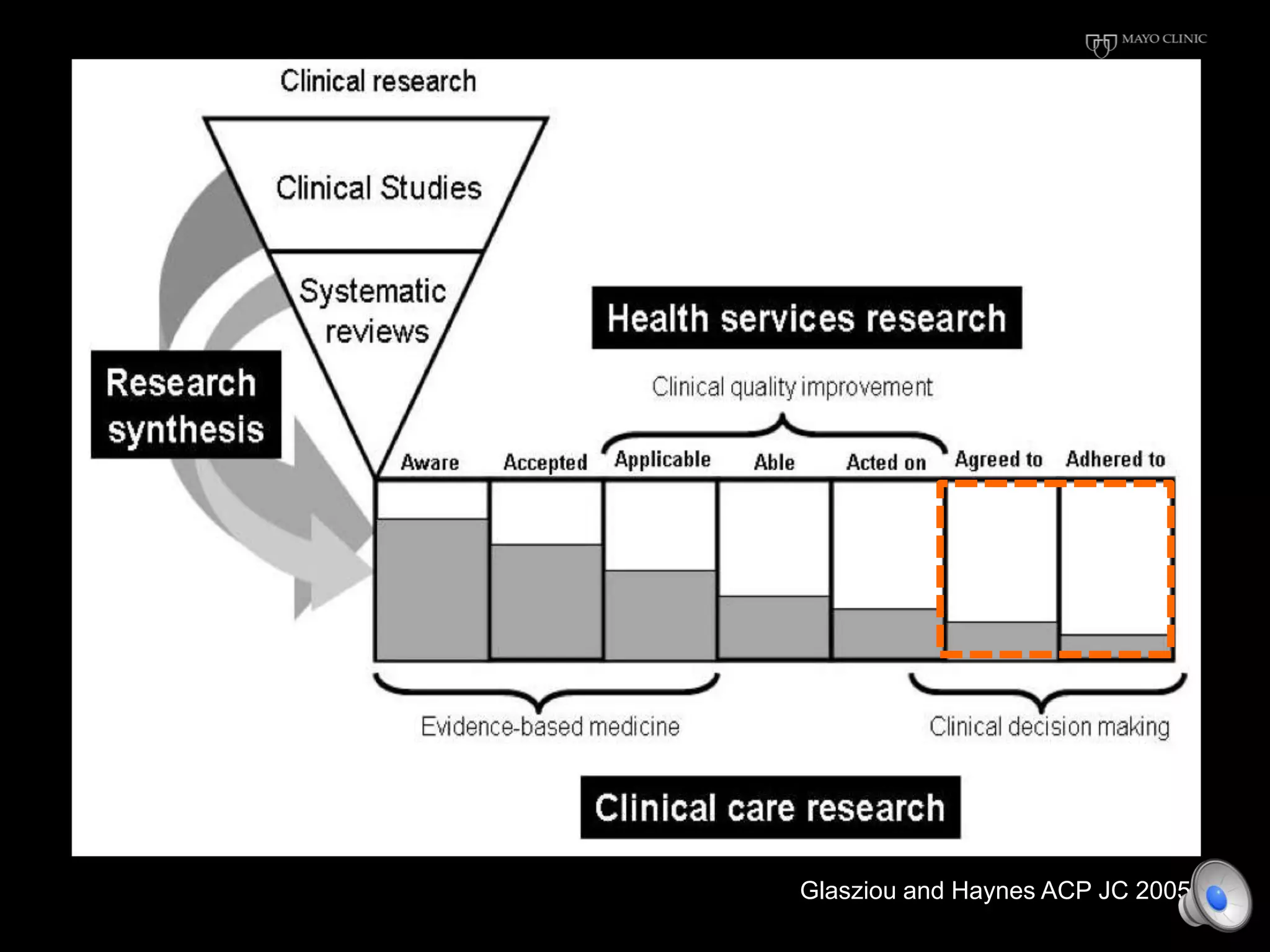

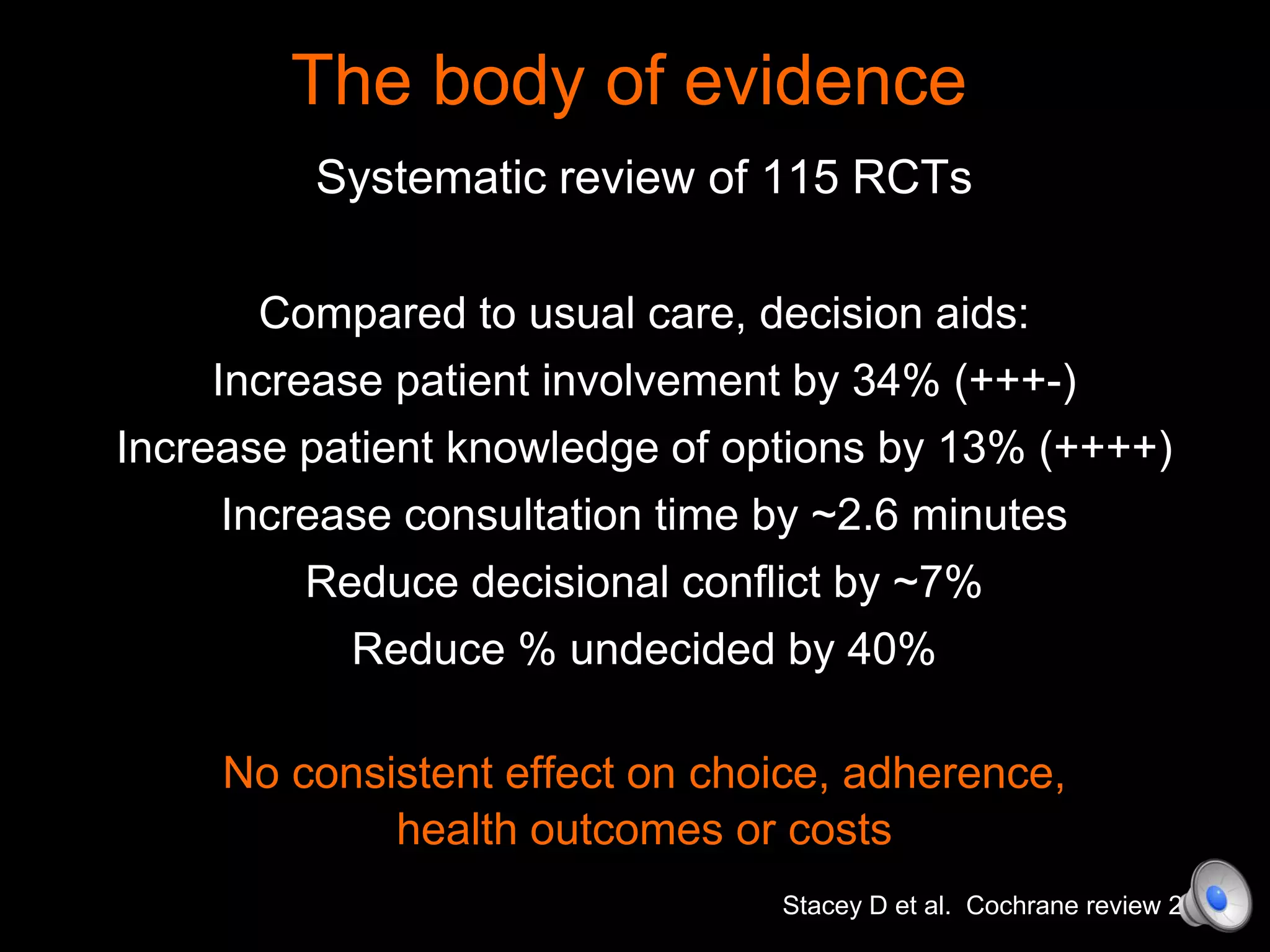

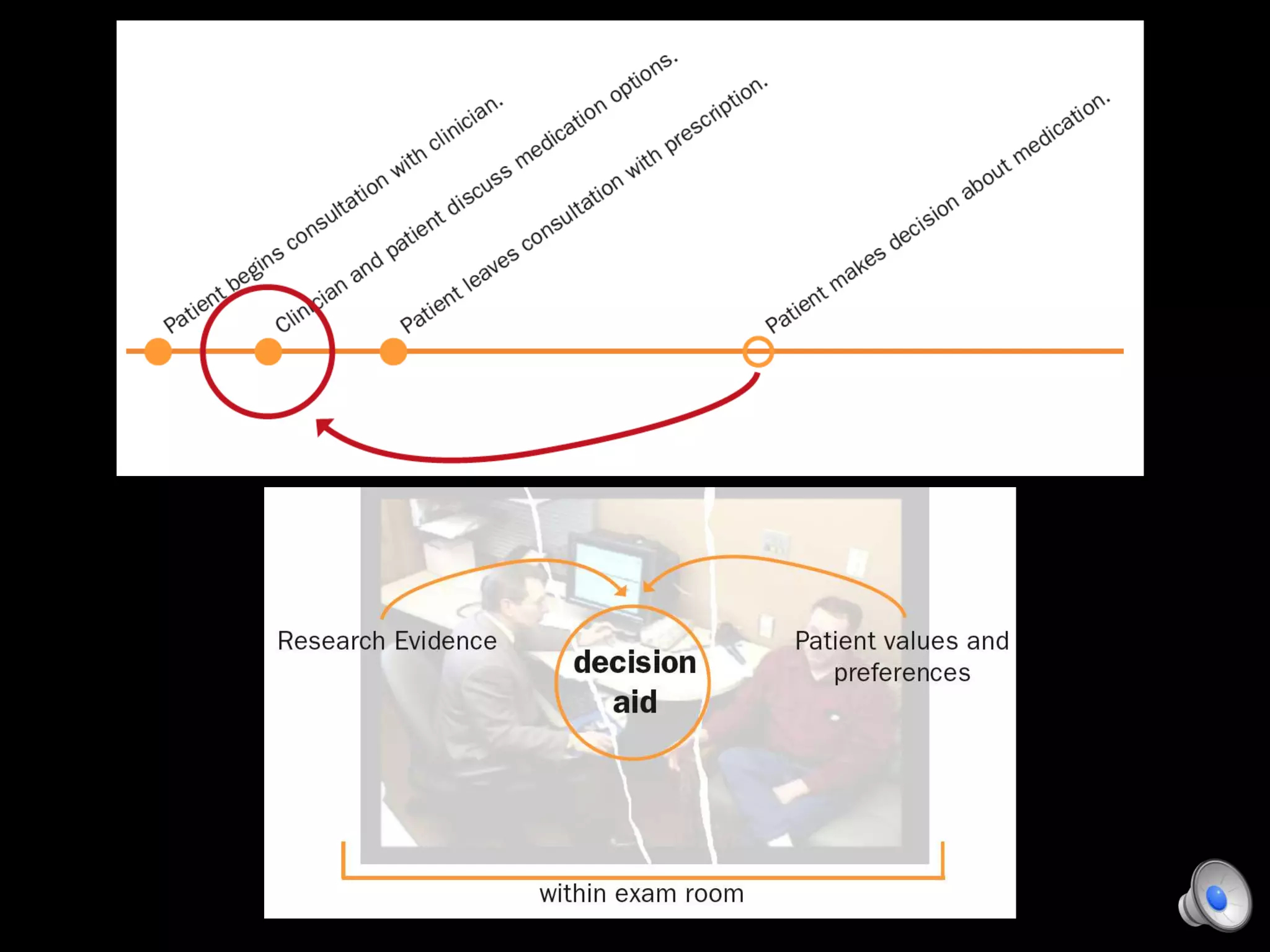

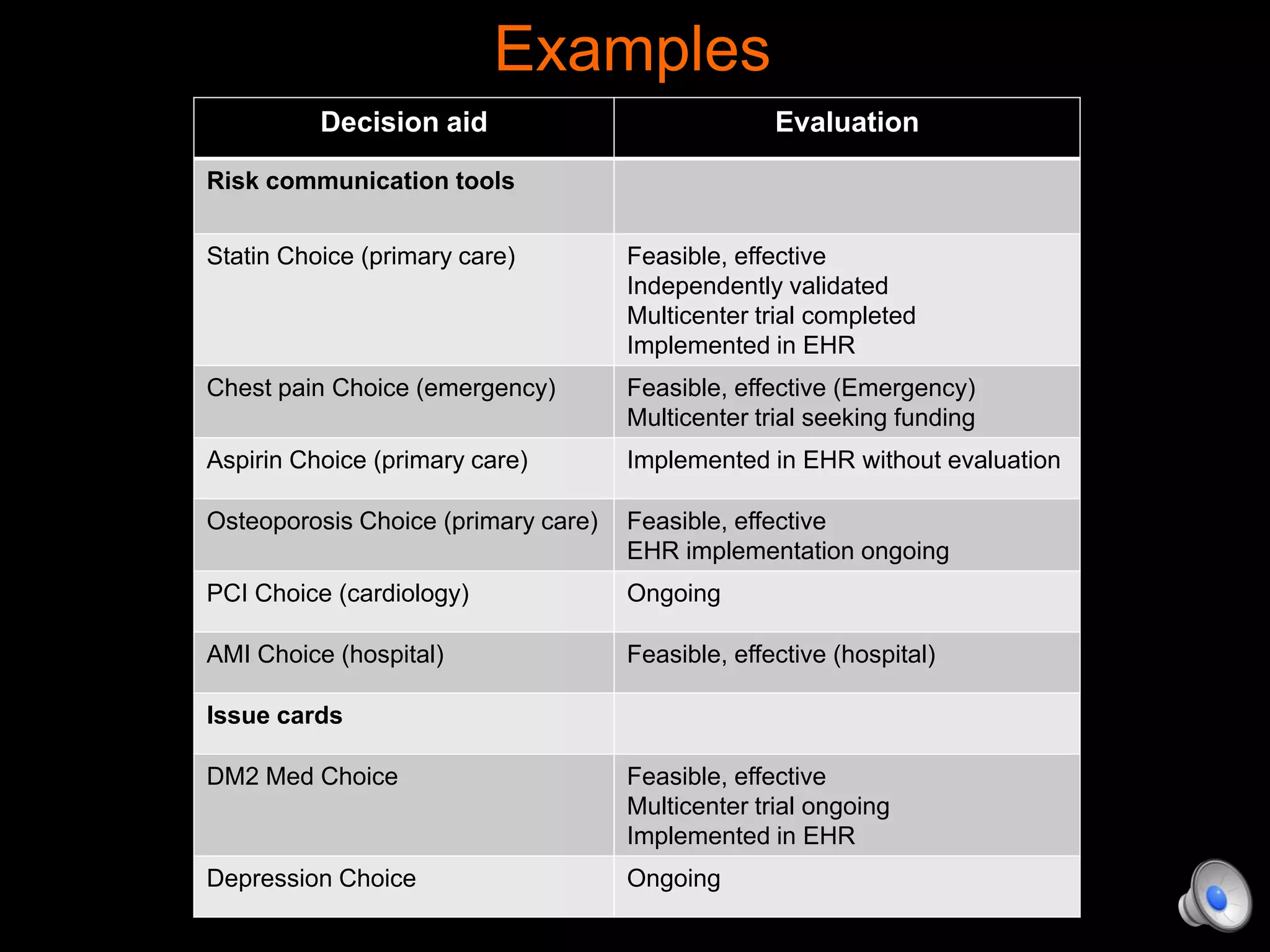

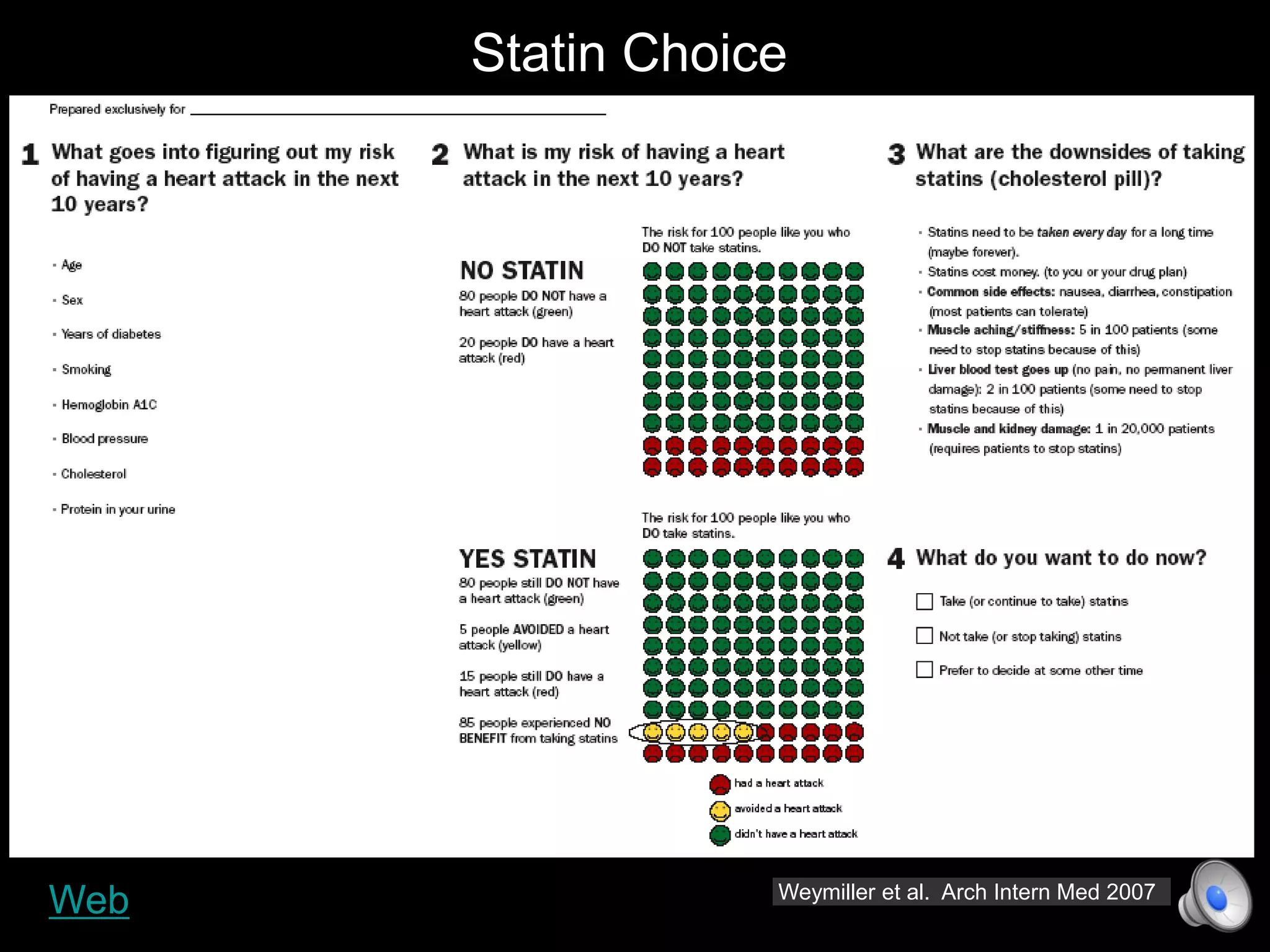

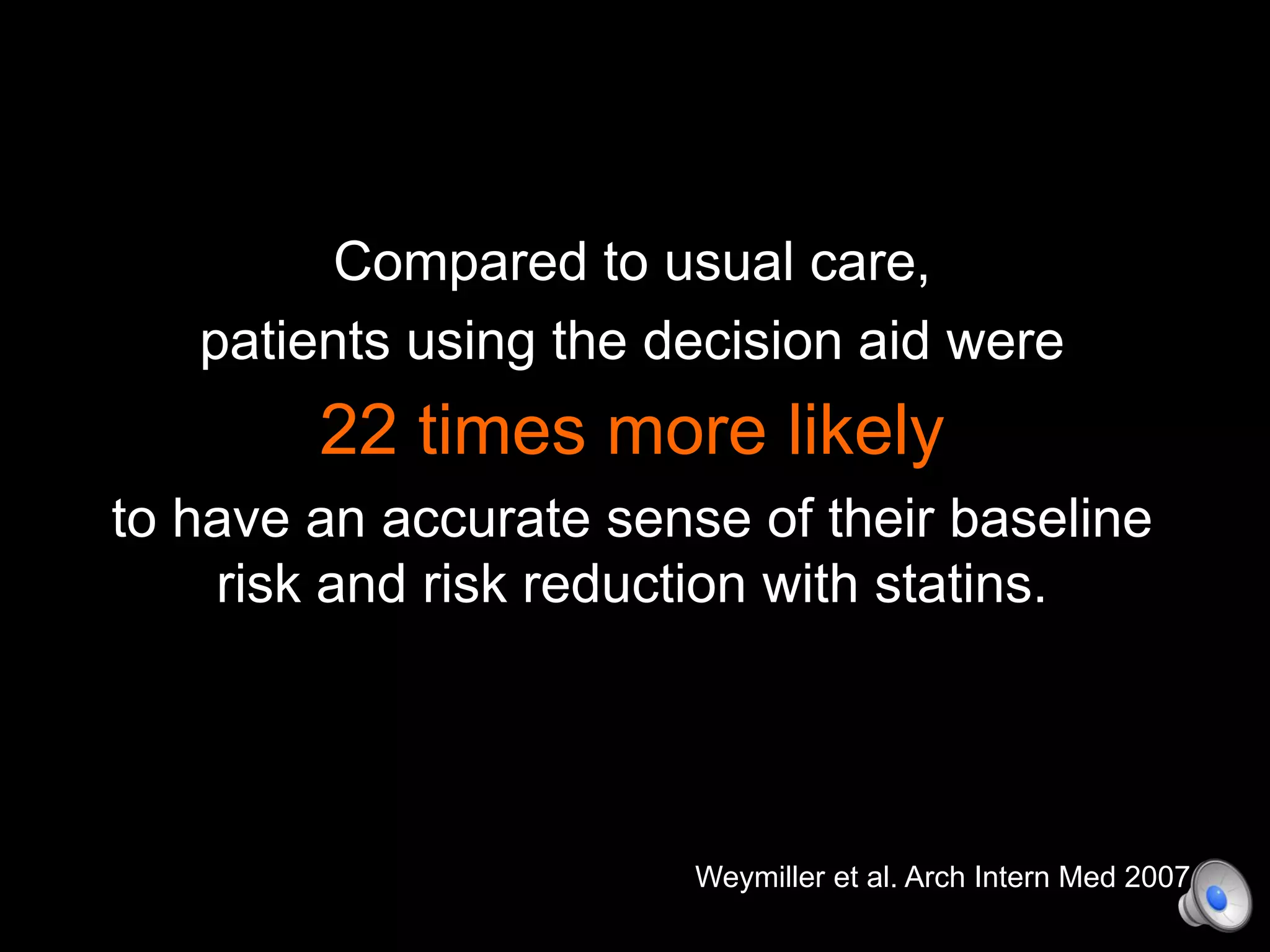

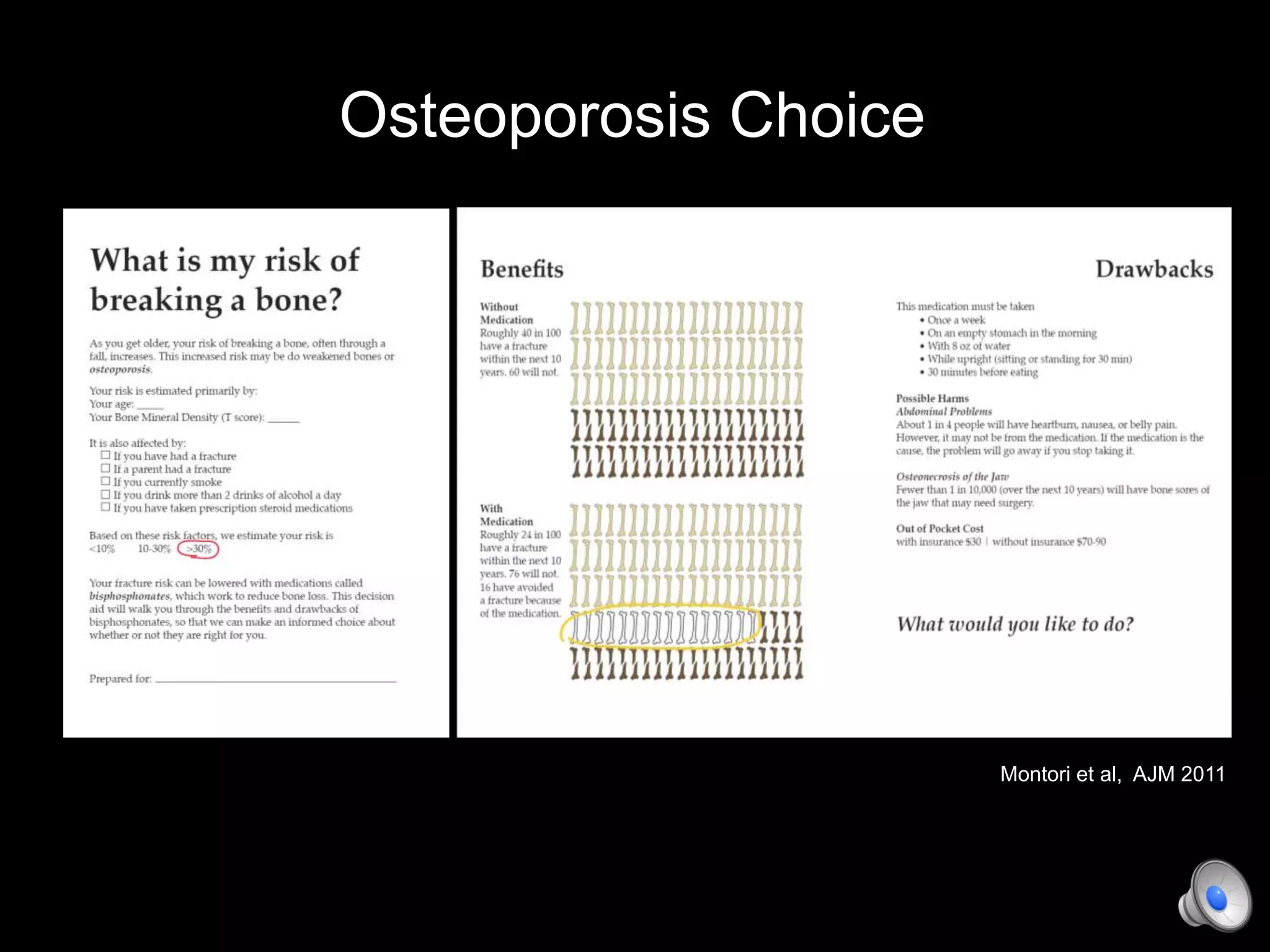

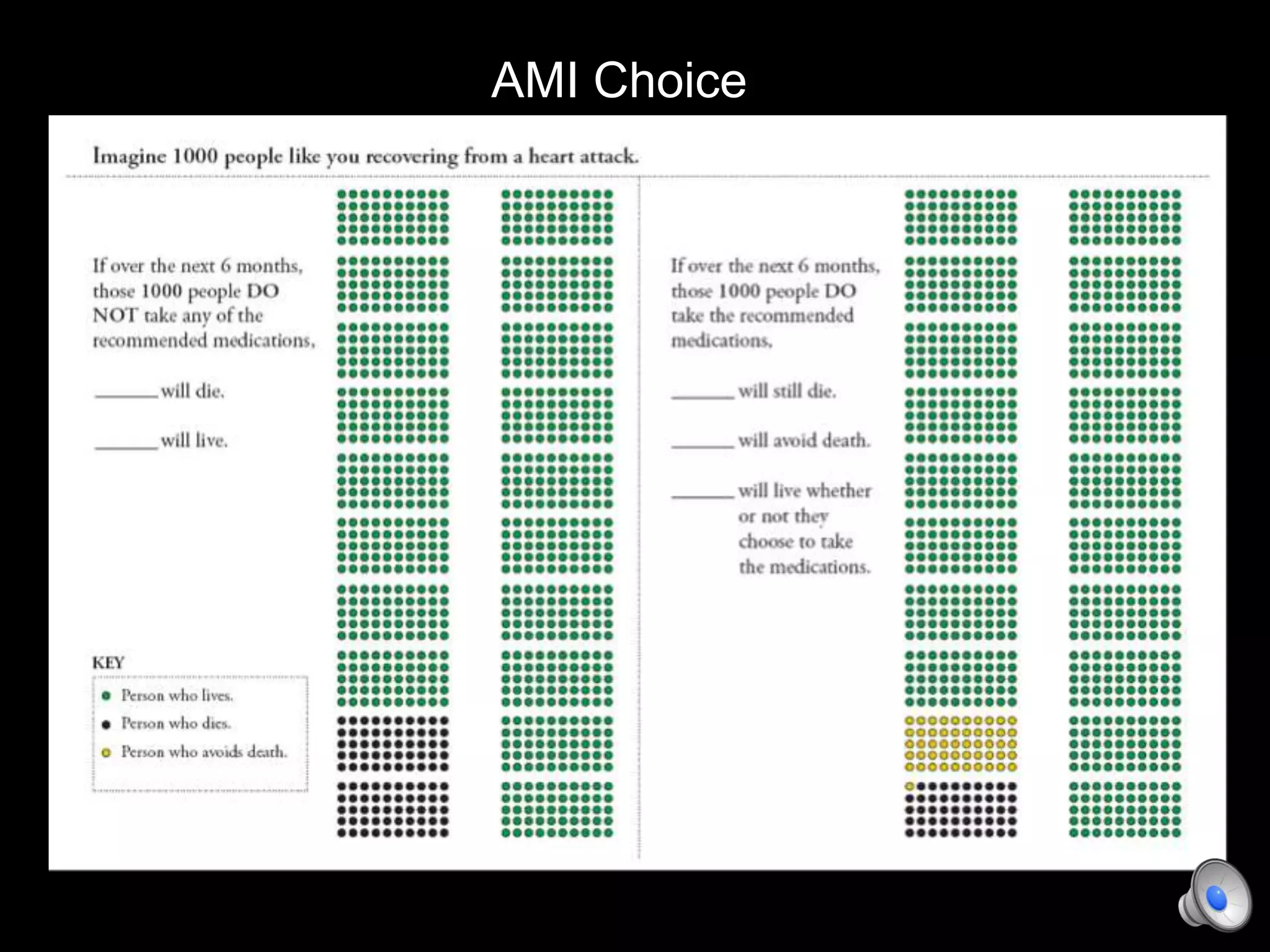

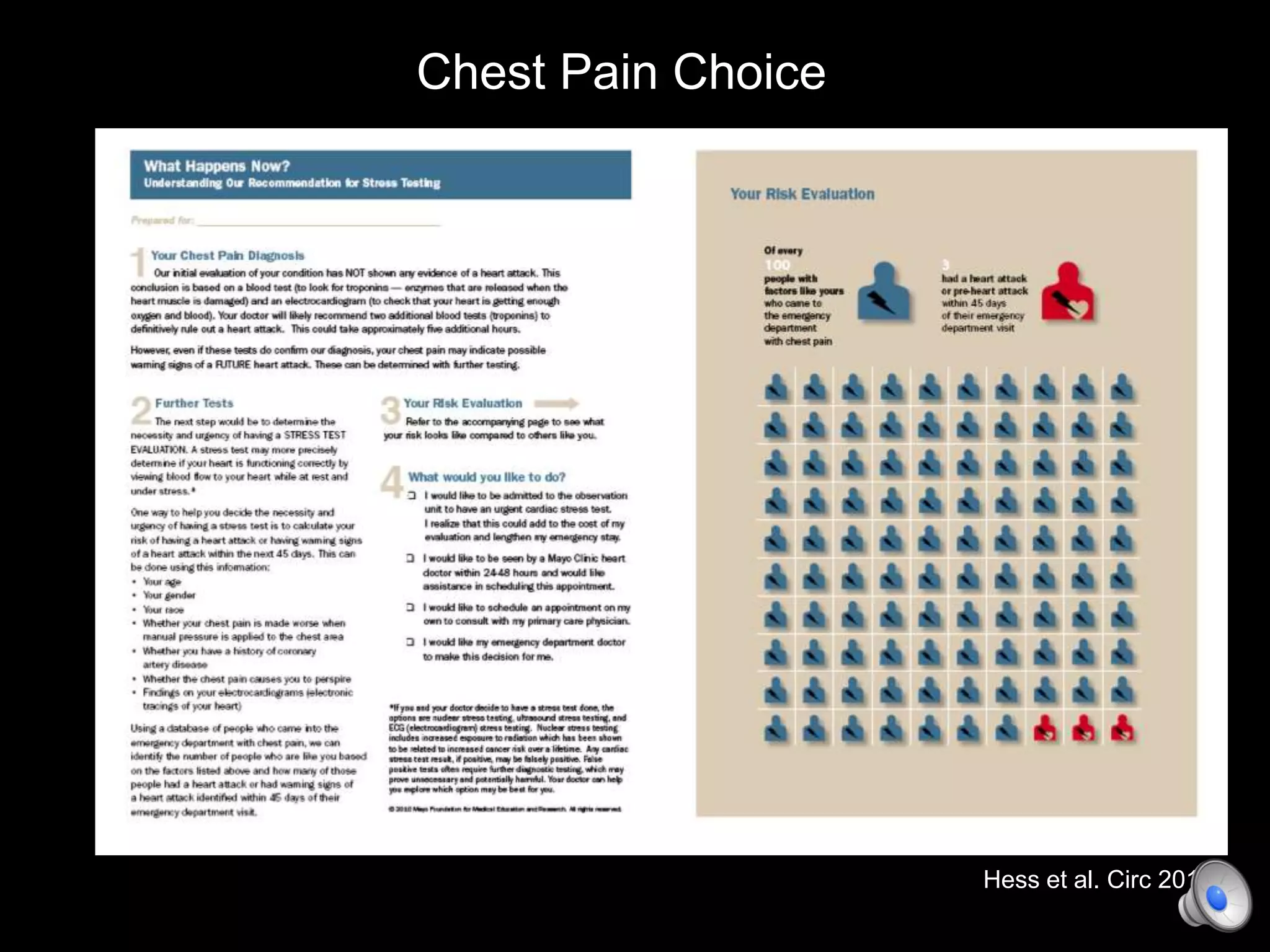

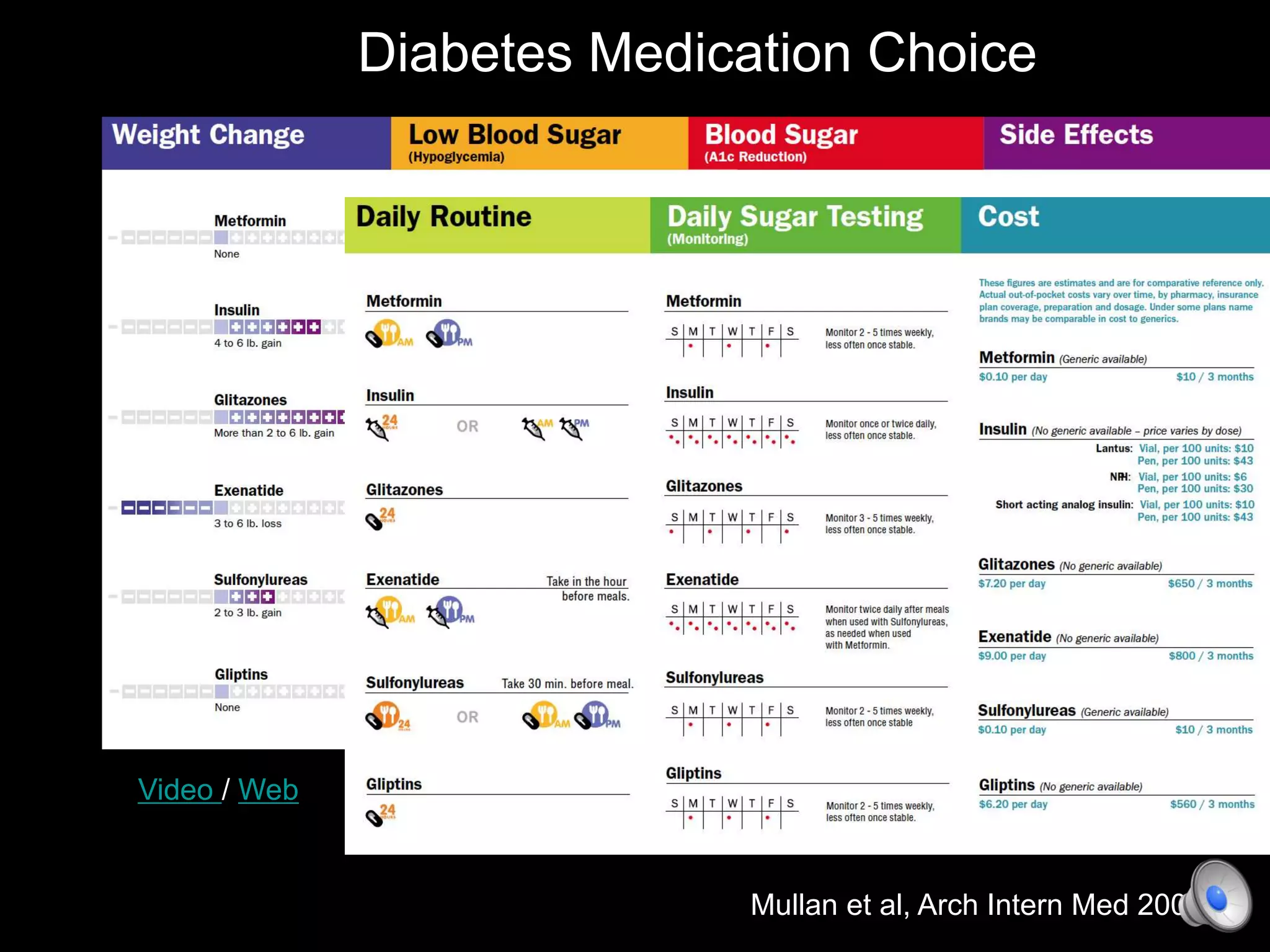

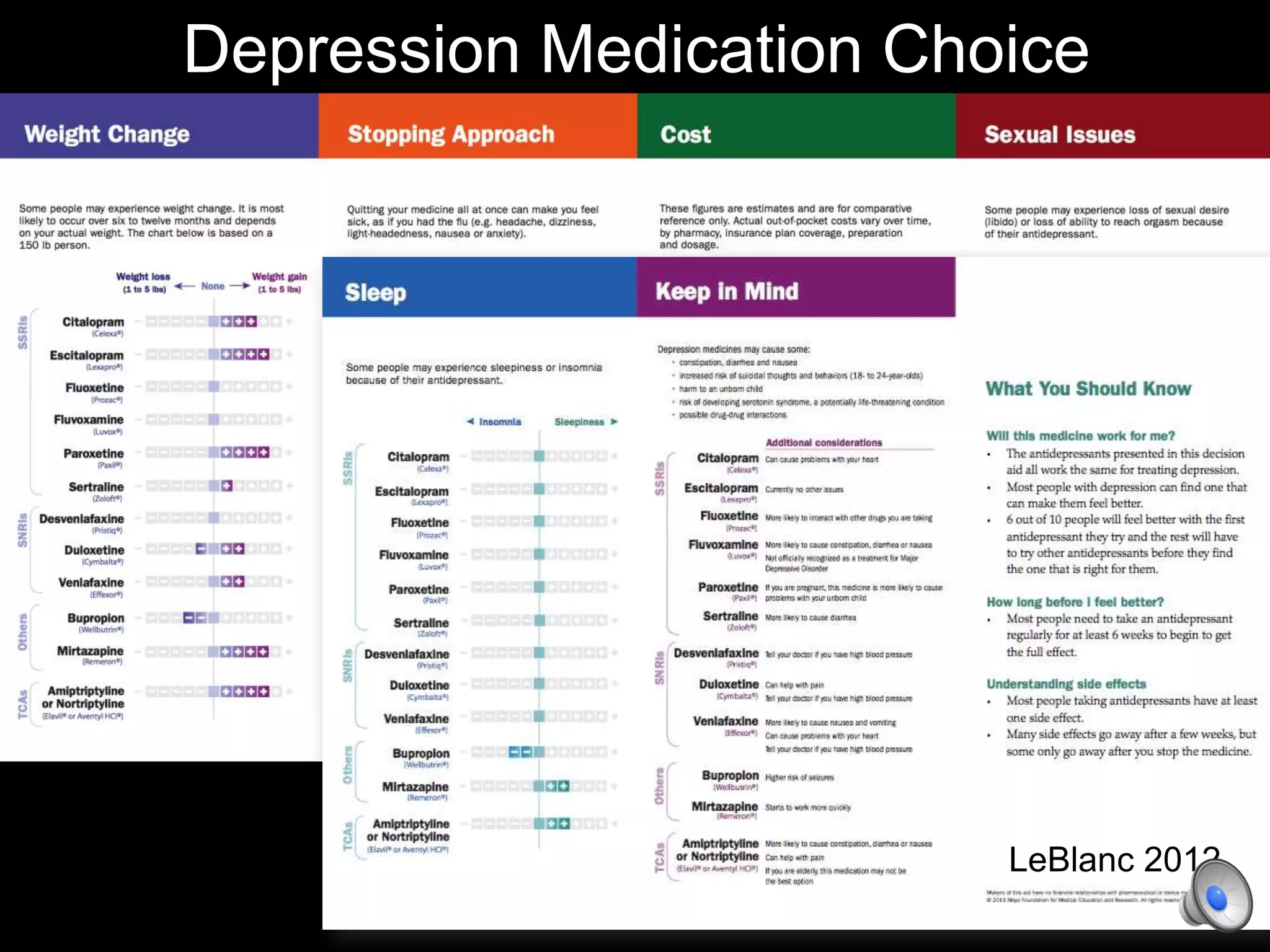

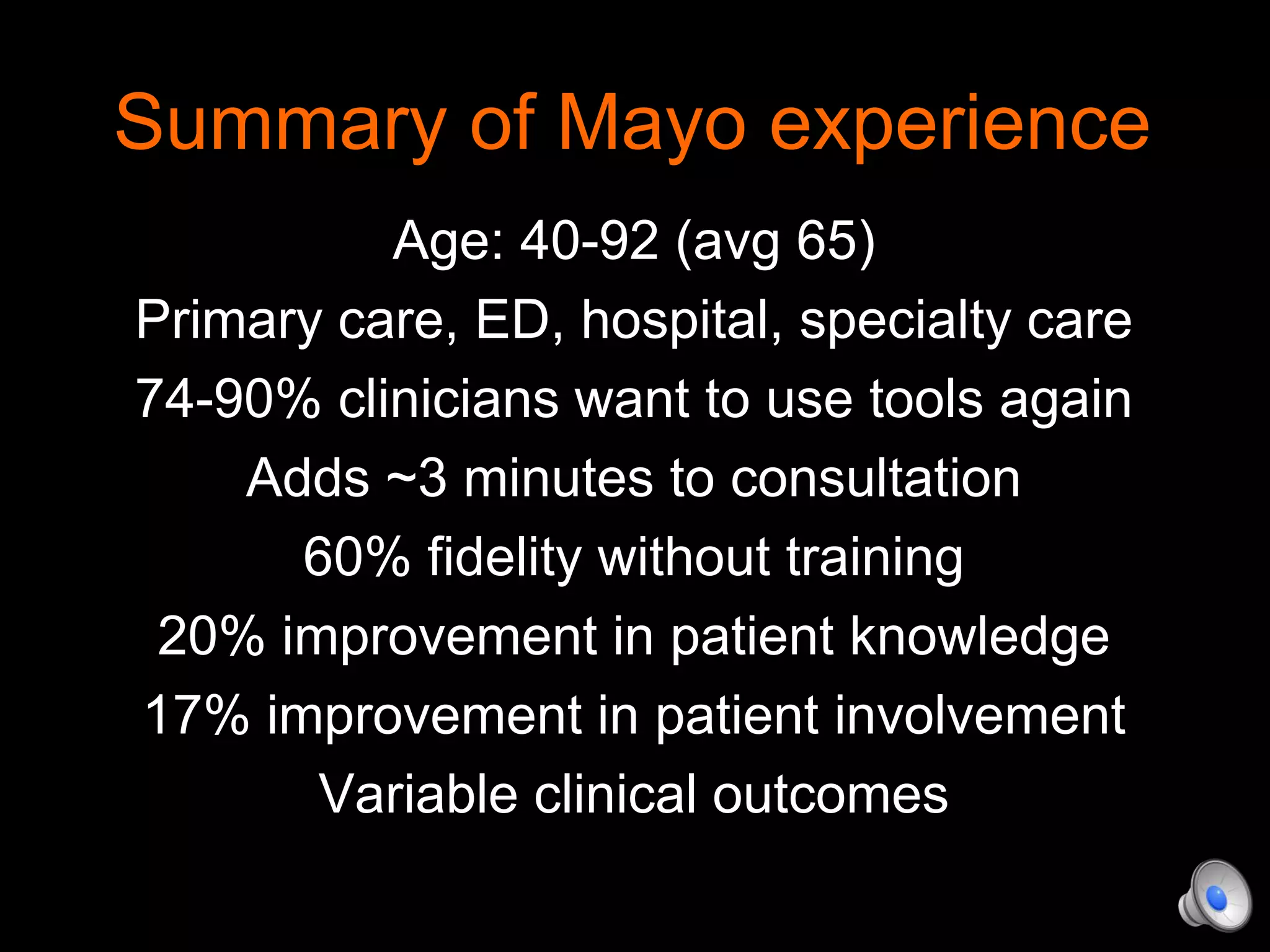

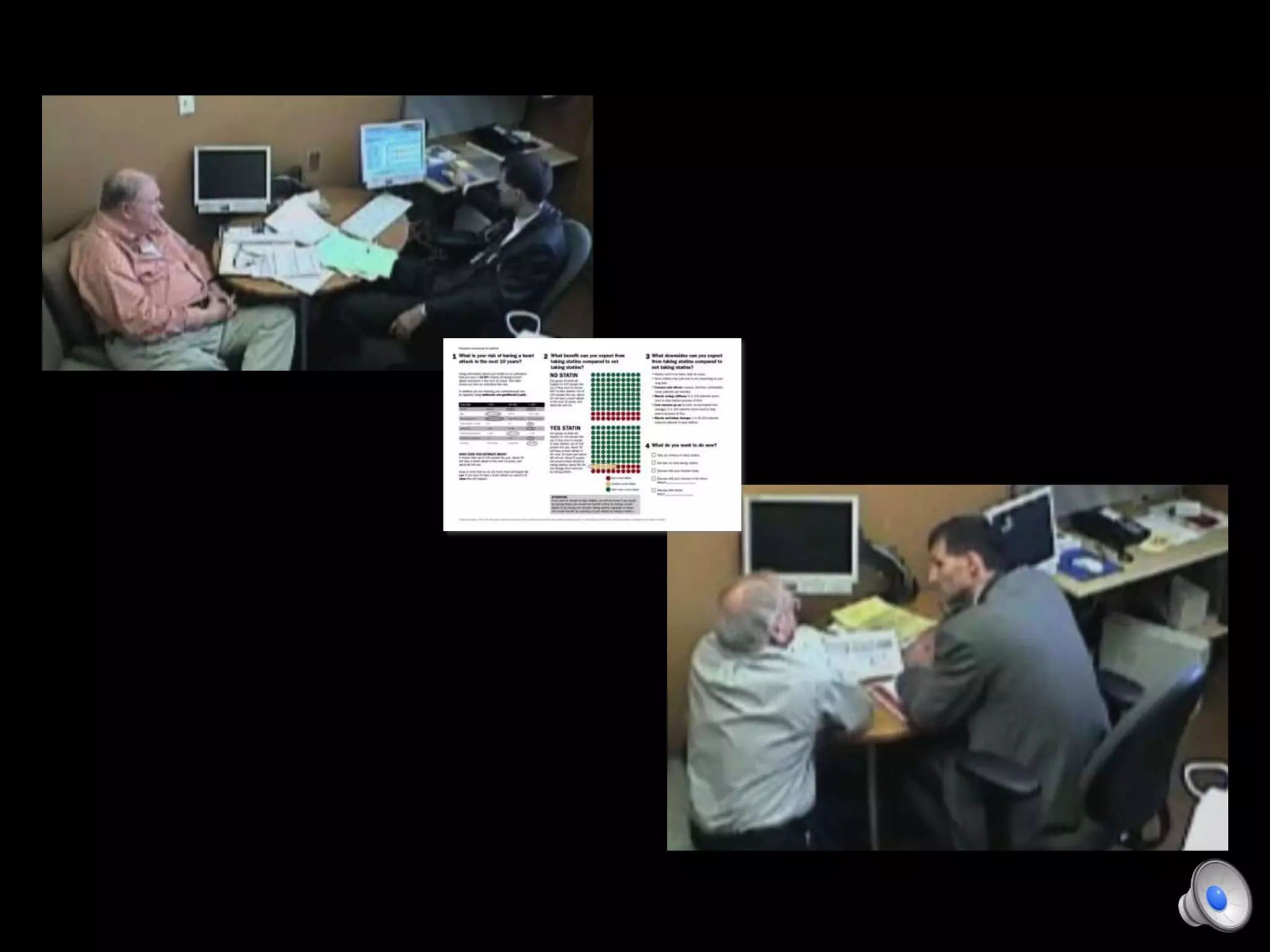

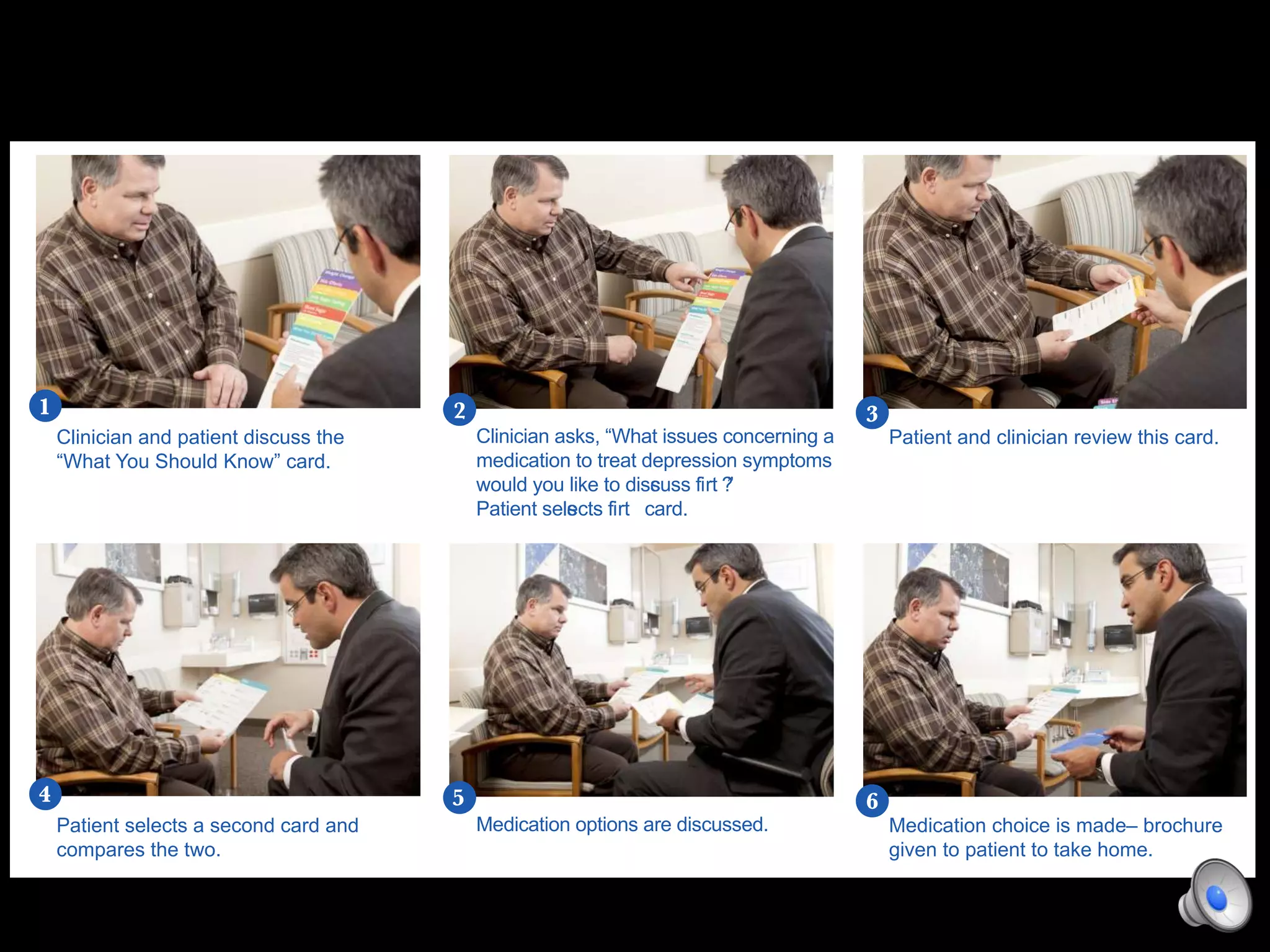

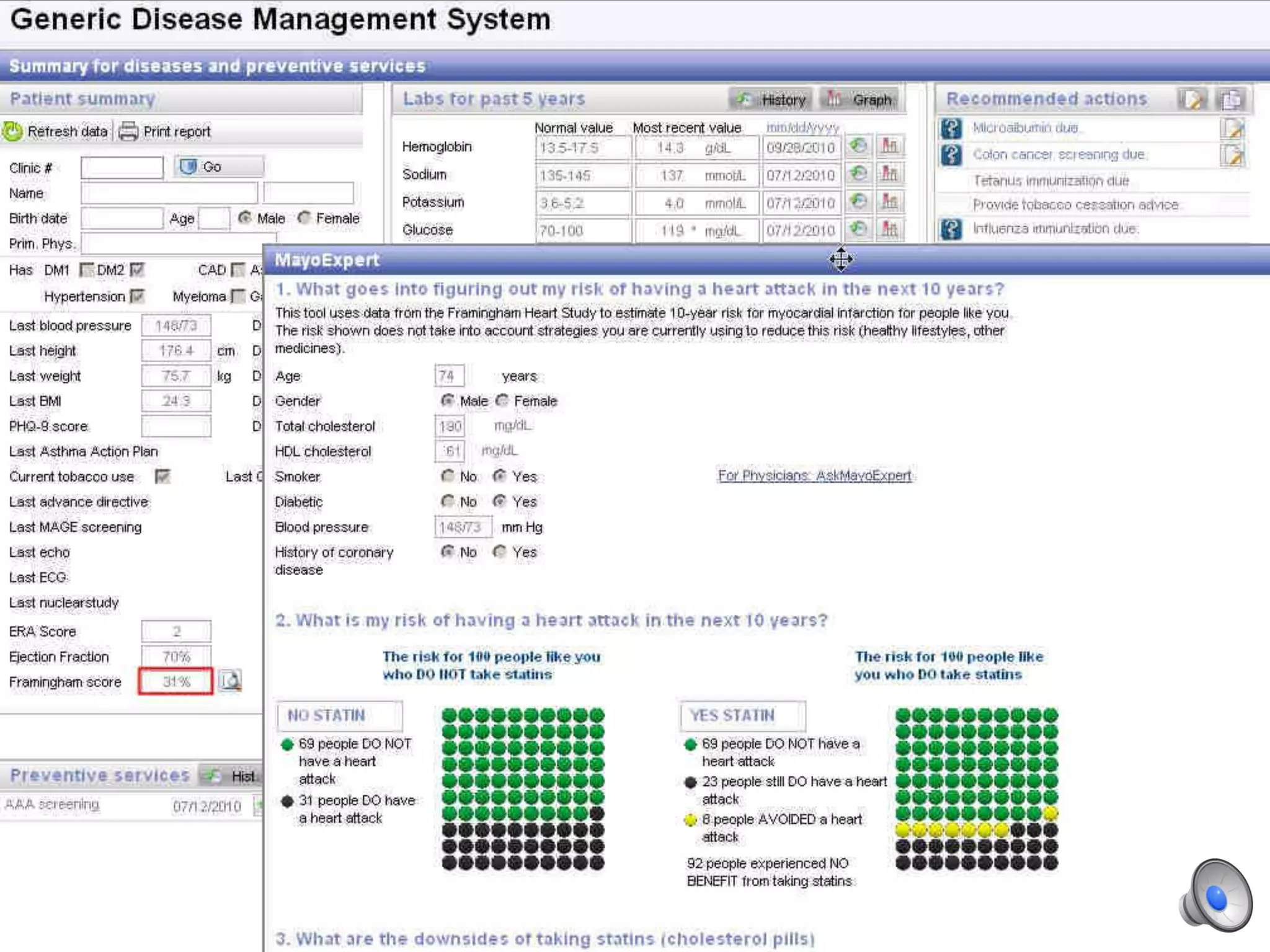

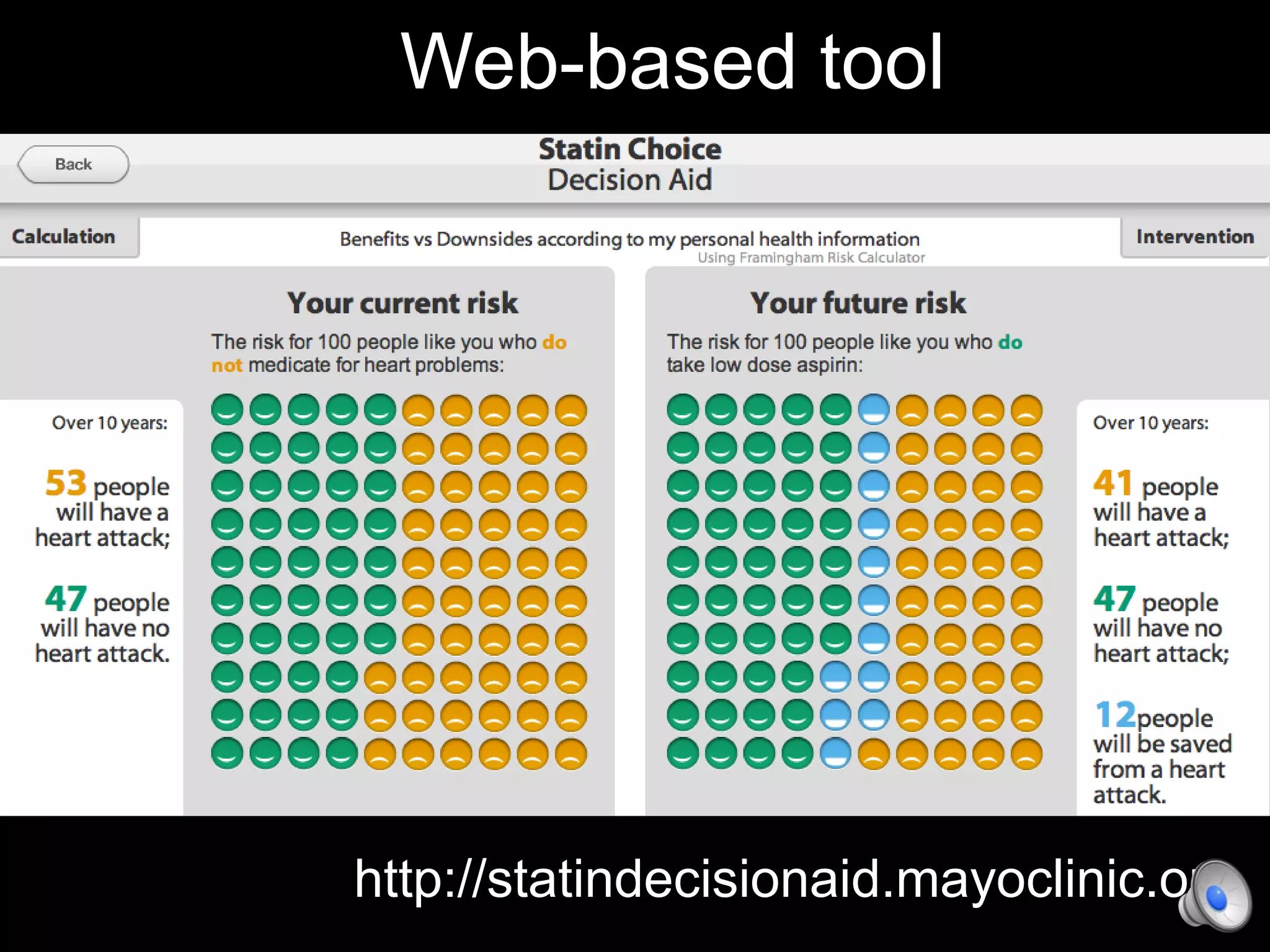

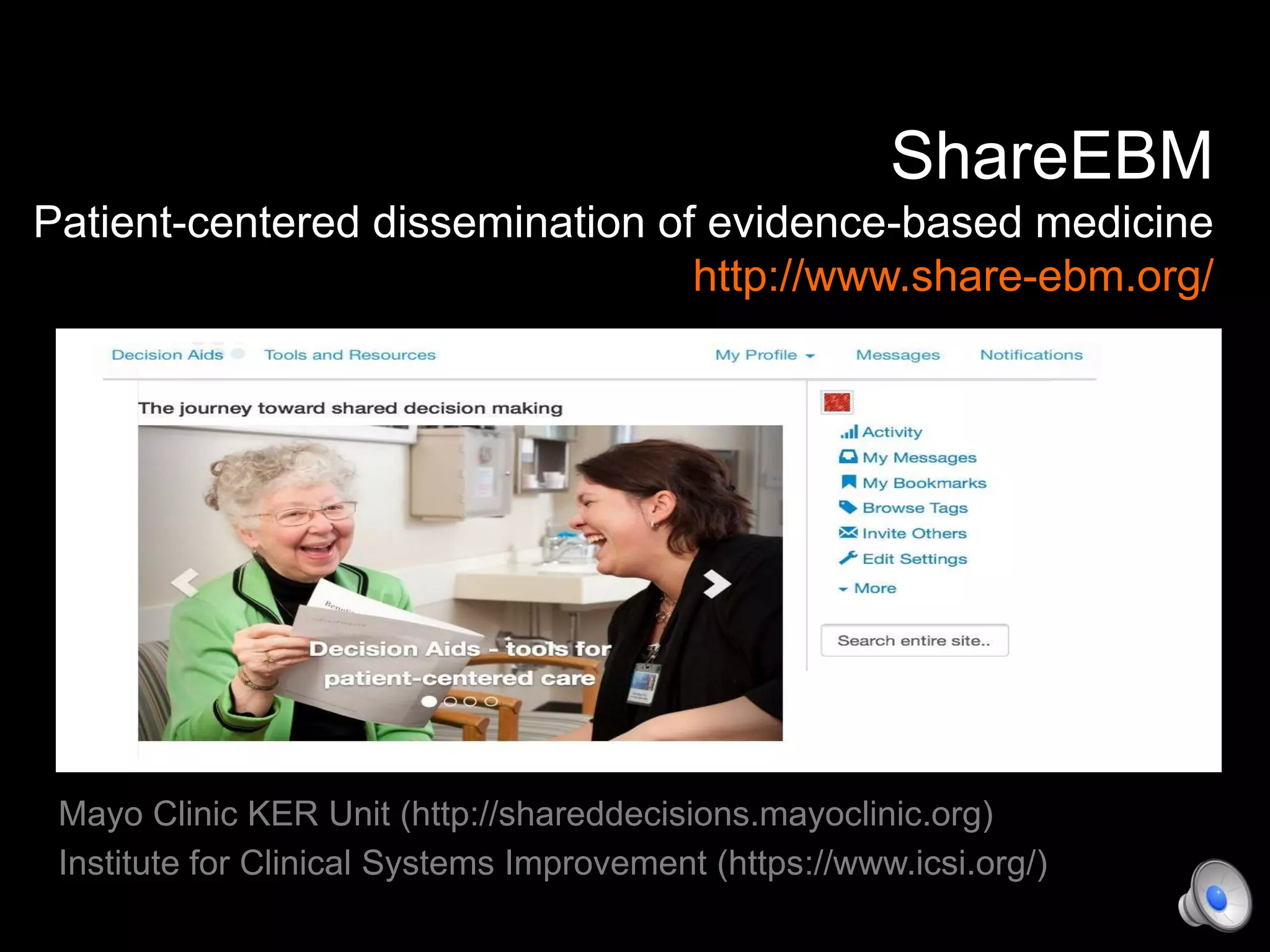

This document discusses using decision aids to promote shared decision making between clinicians and patients. It summarizes research showing that decision aids increase patient involvement and knowledge, reduce decisional conflict, and save consultation time without negatively impacting health outcomes or costs. Examples of effective decision aids for conditions like statin use, osteoporosis, and depression medication are provided. Implementing decision aids in clinical practice adds only a few minutes to visits but significantly improves patient understanding and involvement in healthcare decisions.