The document discusses the need for evidence-based medicine (EBM) in clinical practice and challenges incorporating EBM. It finds that:

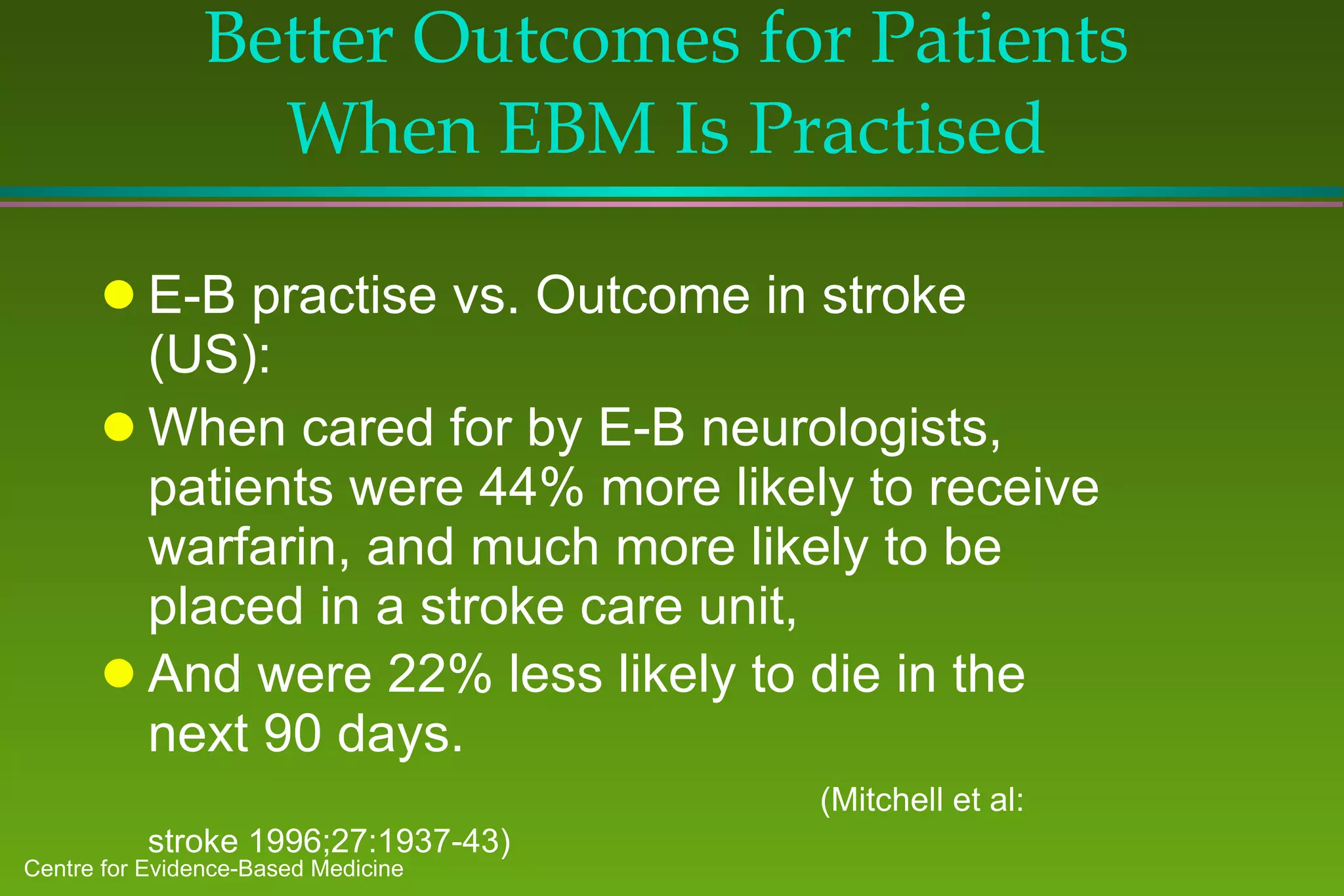

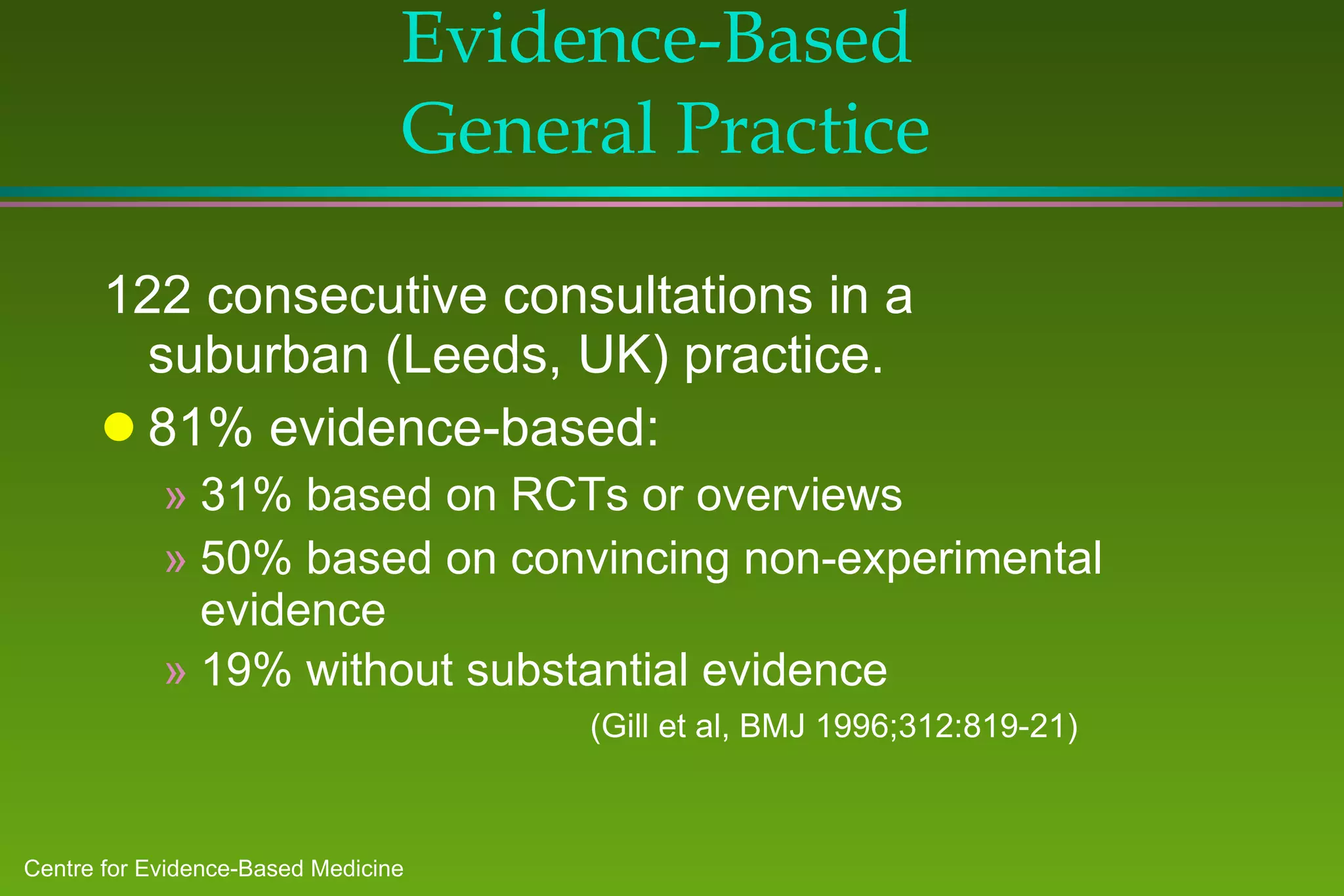

1) A study of patients at a general medicine hospital found that 82% received evidence-based care, with treatments for 53% justified by randomized controlled trials or reviews and 29% by convincing non-experimental evidence.

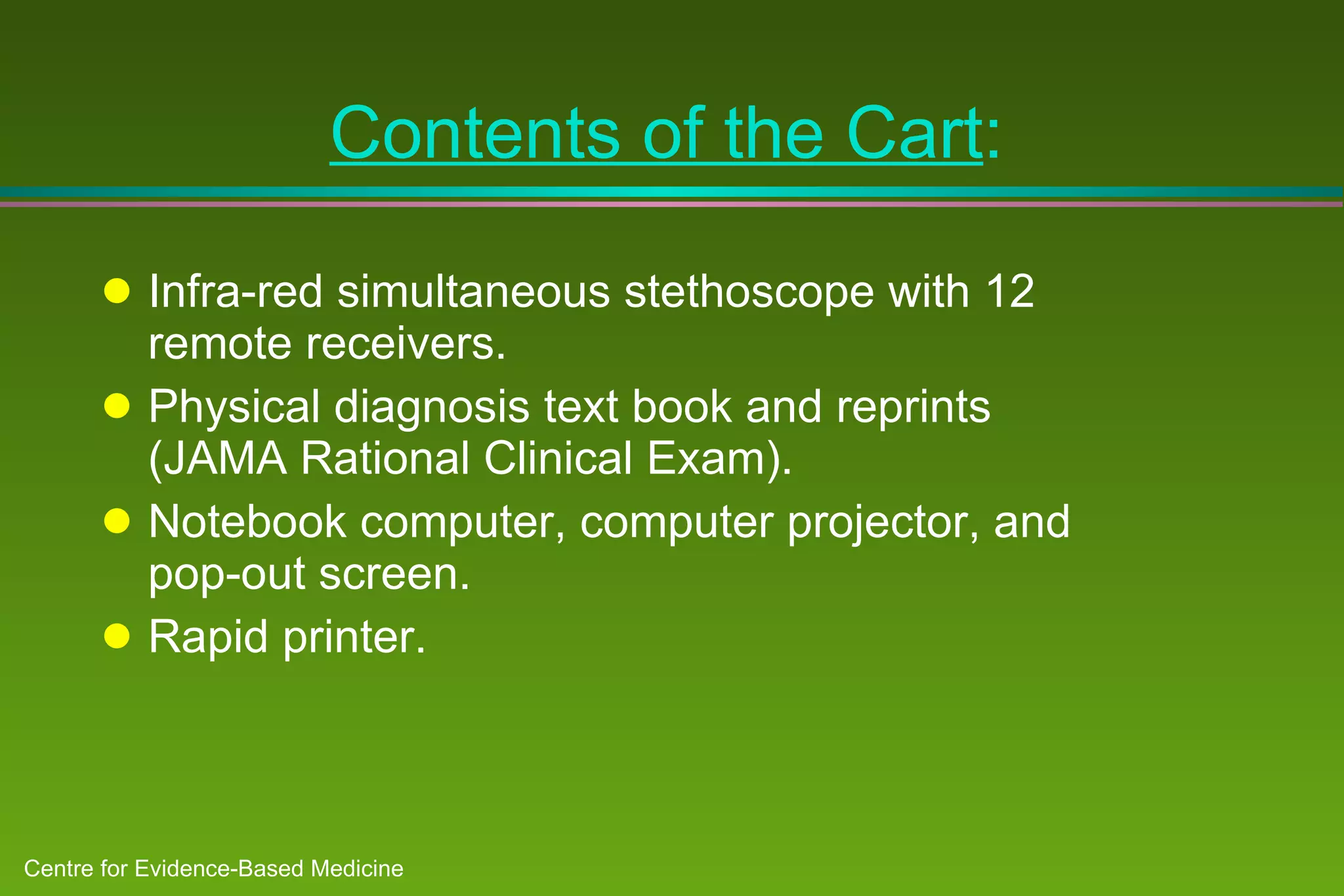

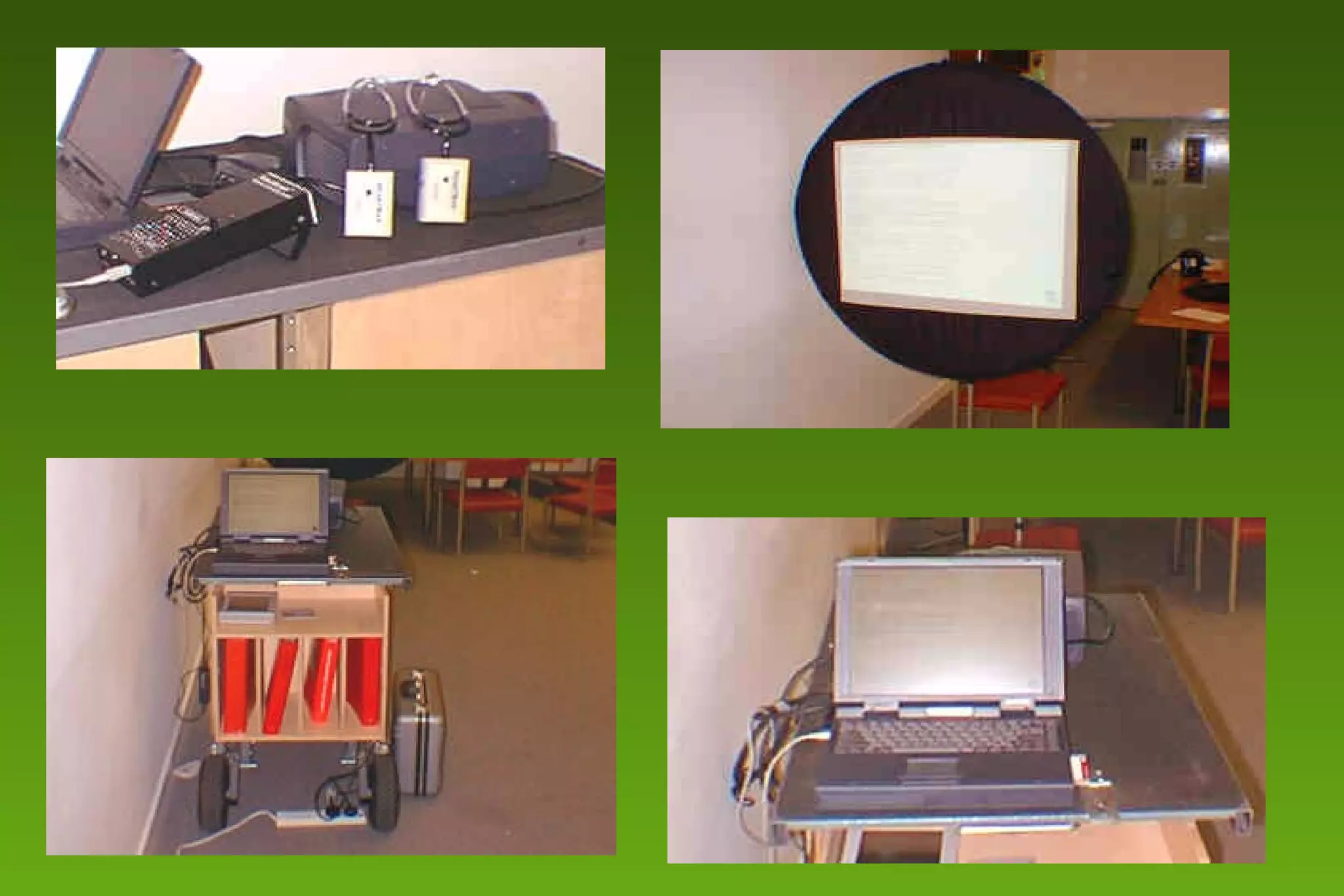

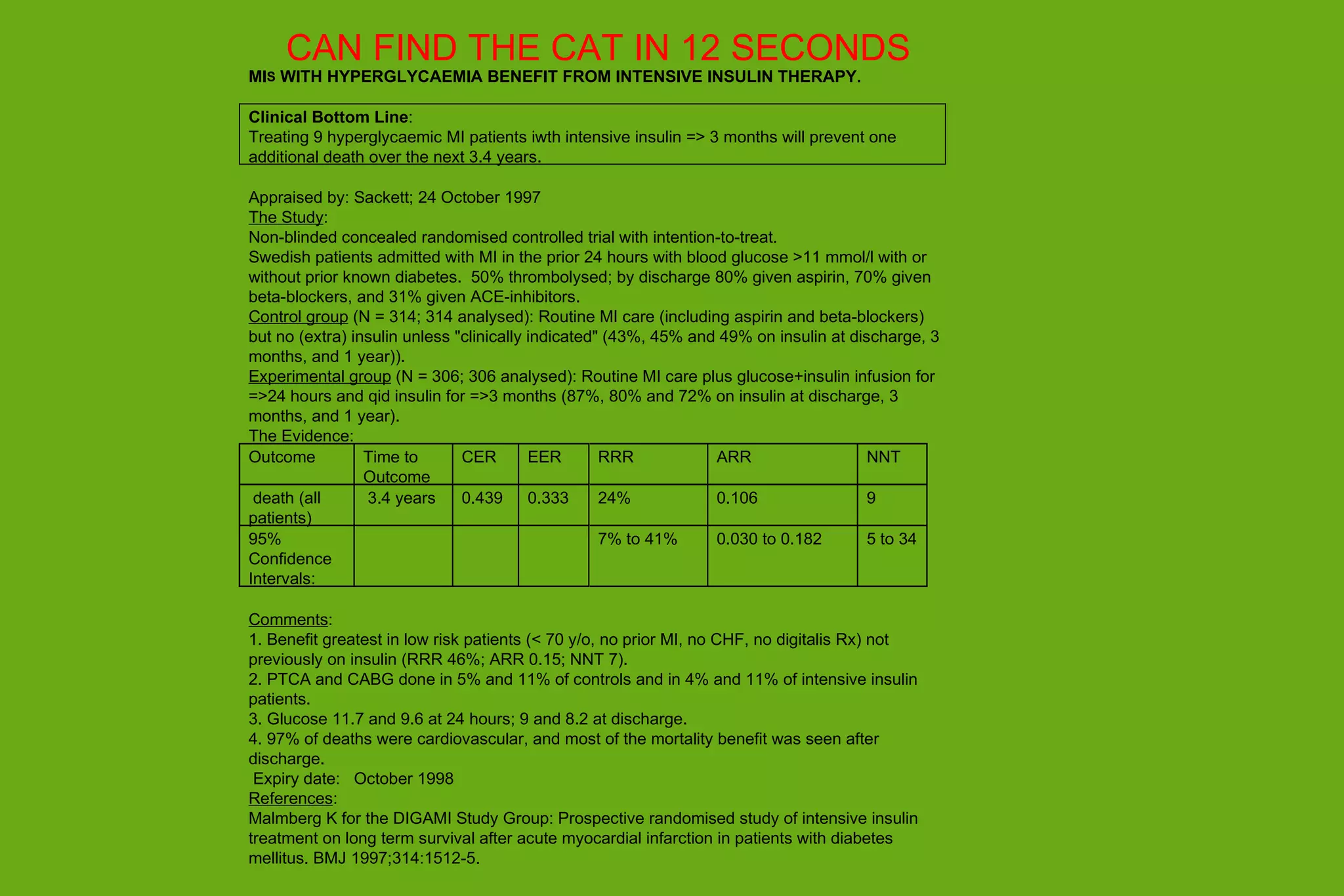

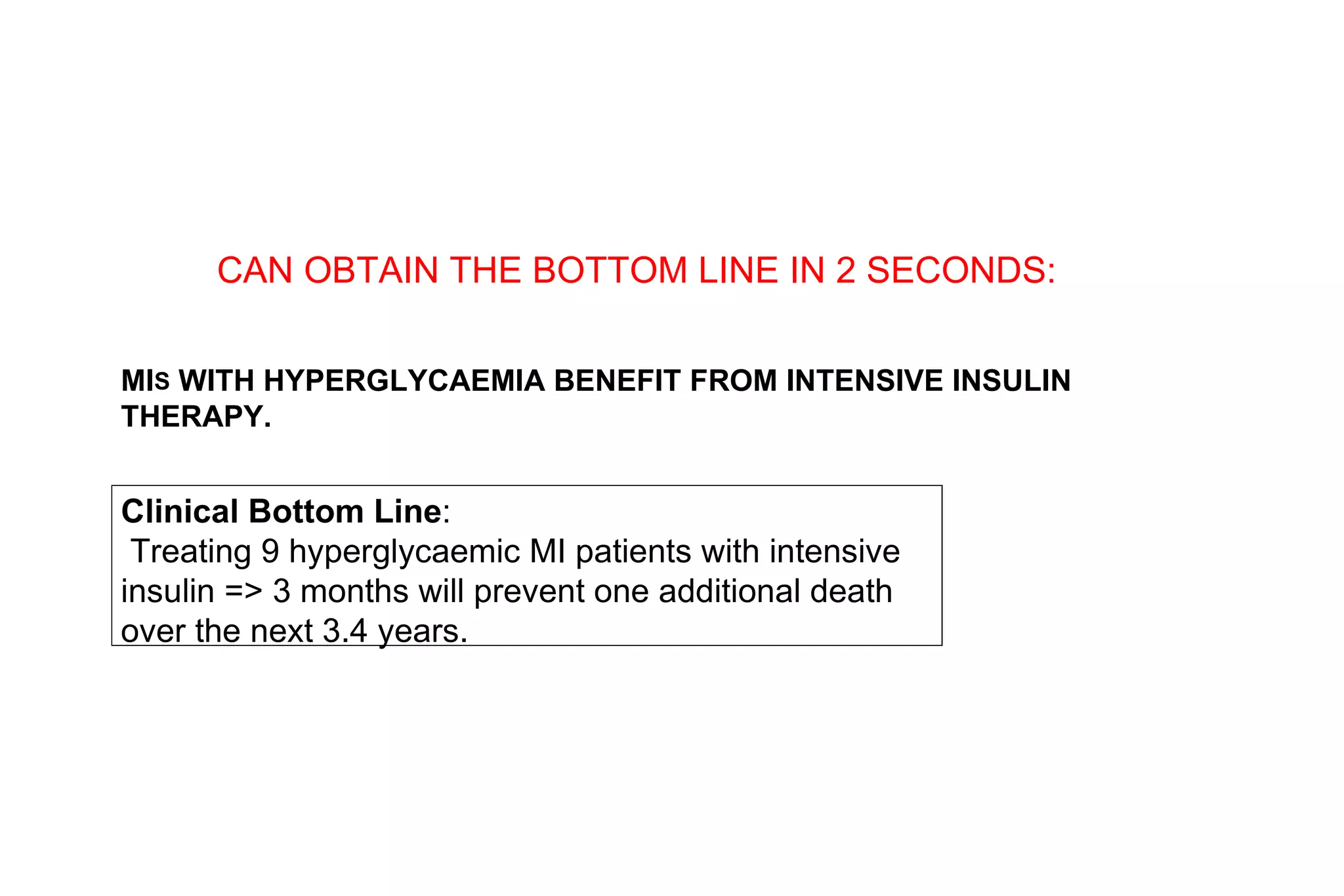

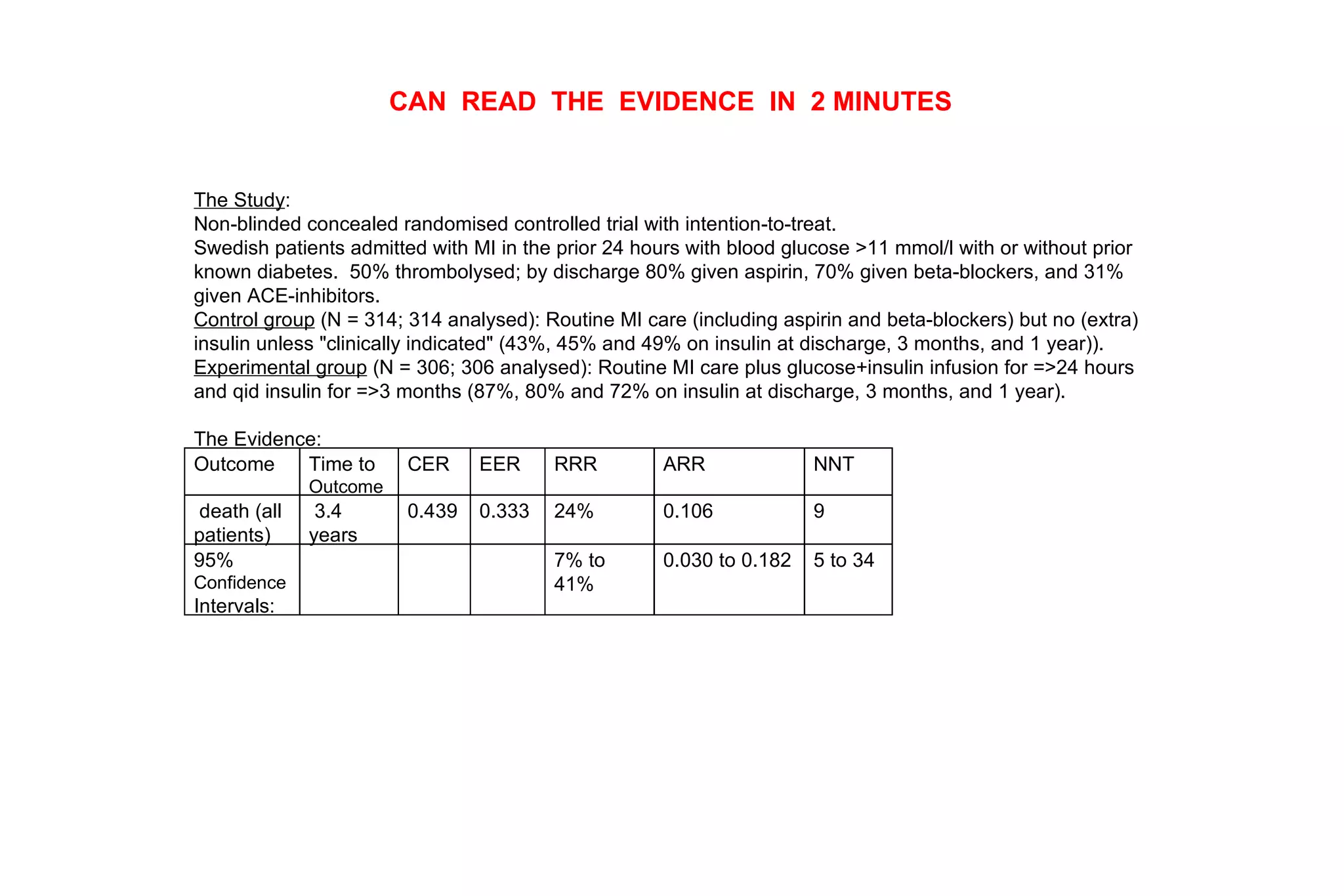

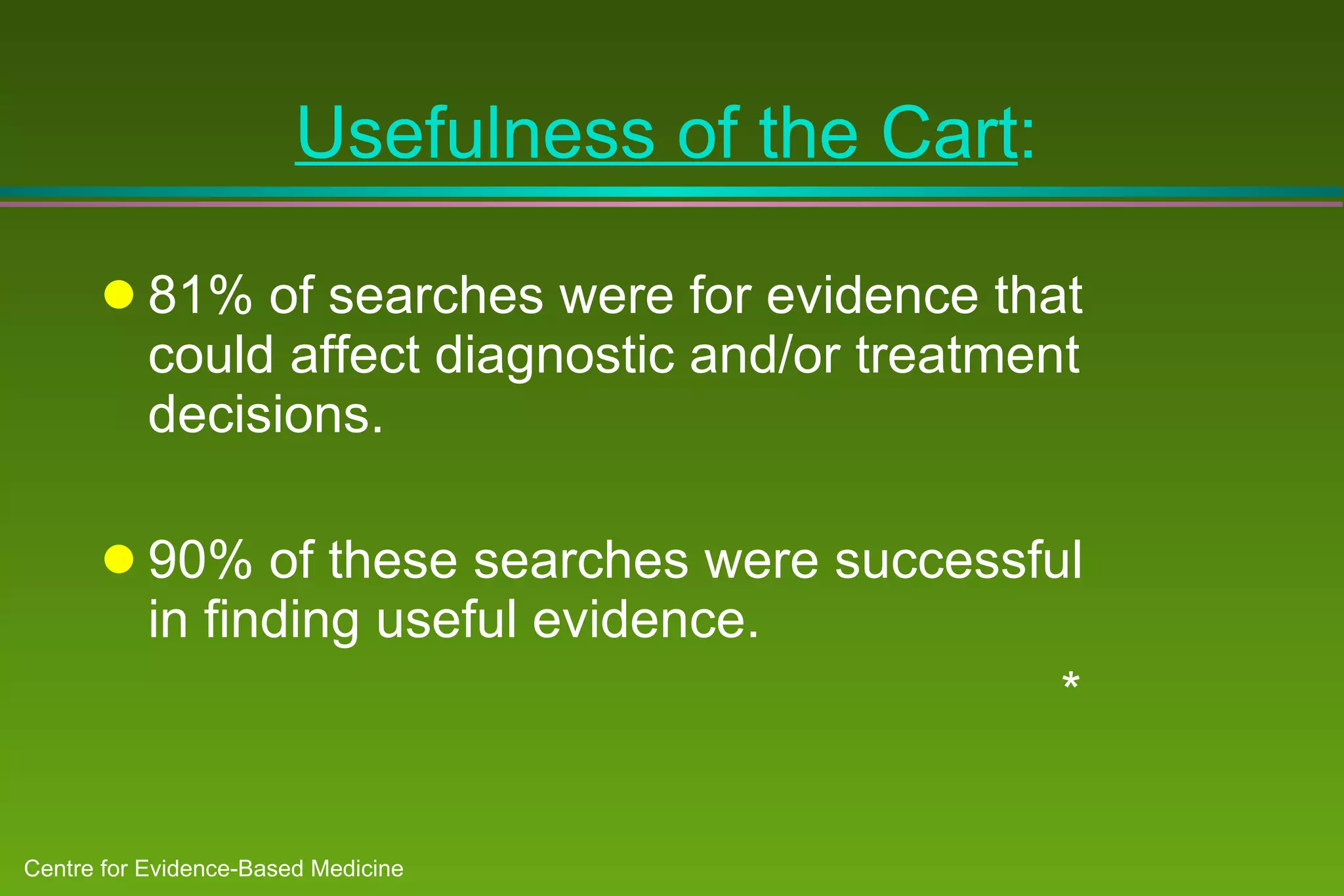

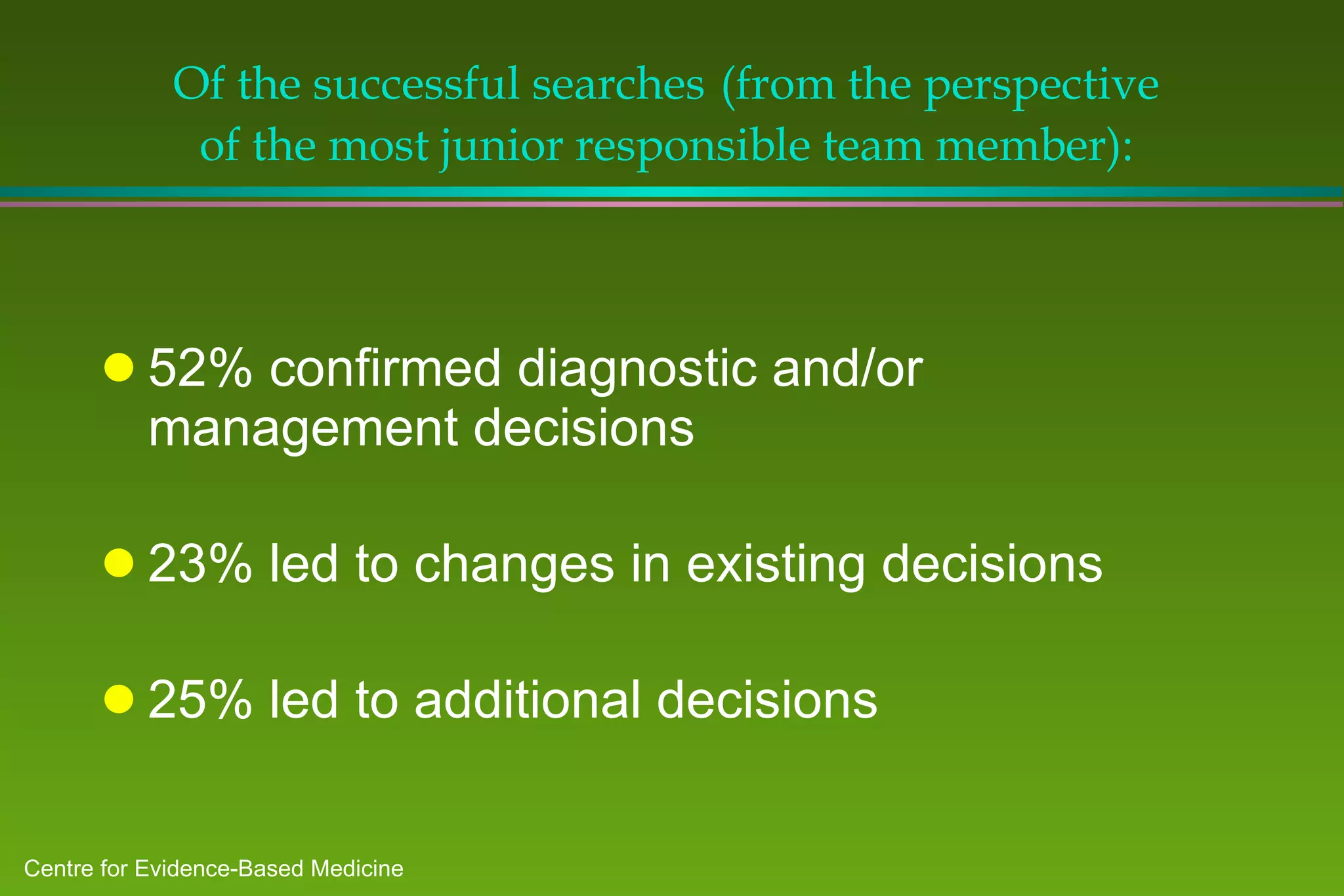

2) Barriers to practicing EBM include lack of time and access to information at the point of care. Bringing a "cart" of medical evidence resources to patient rounds increased evidence-based searches and decisions.

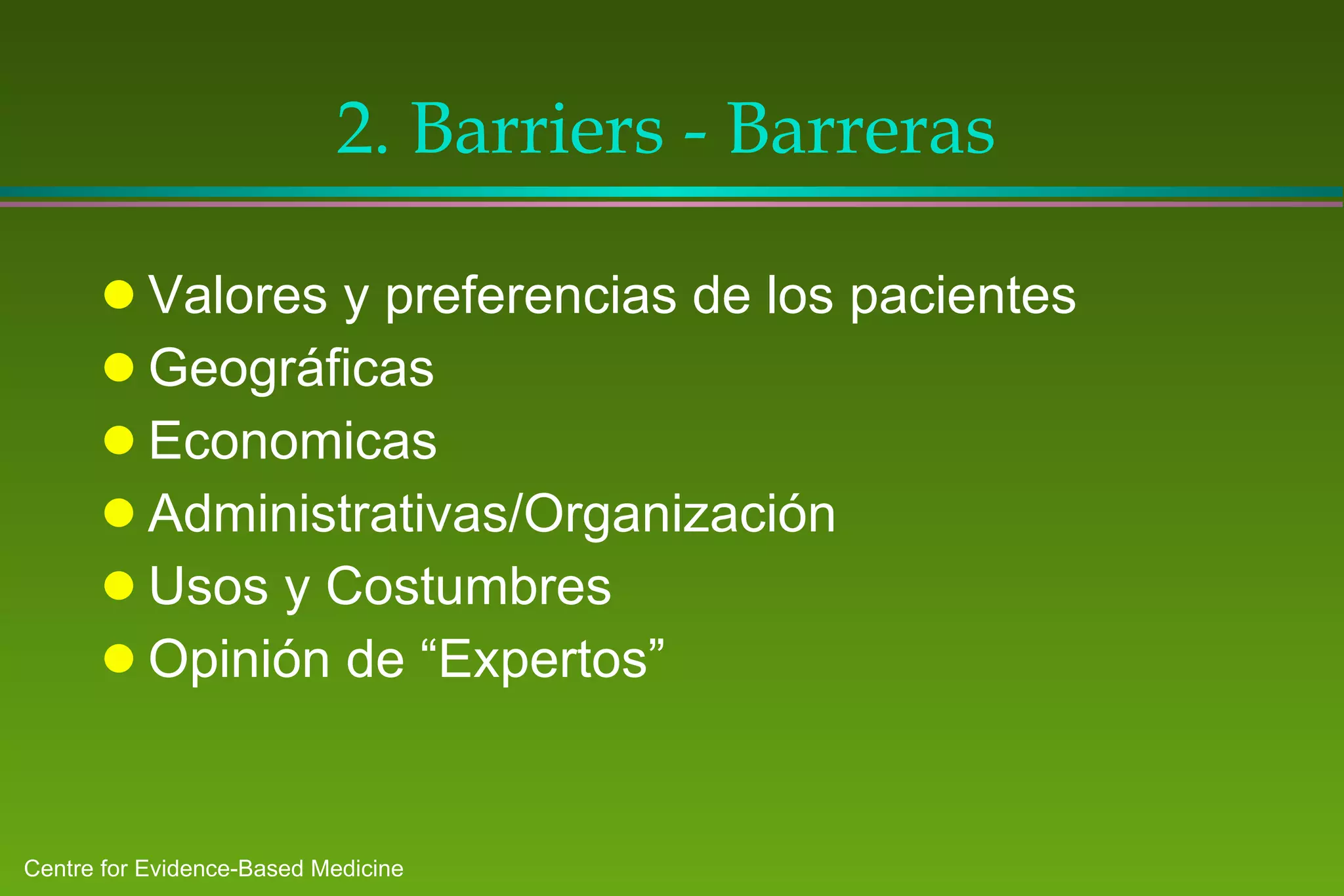

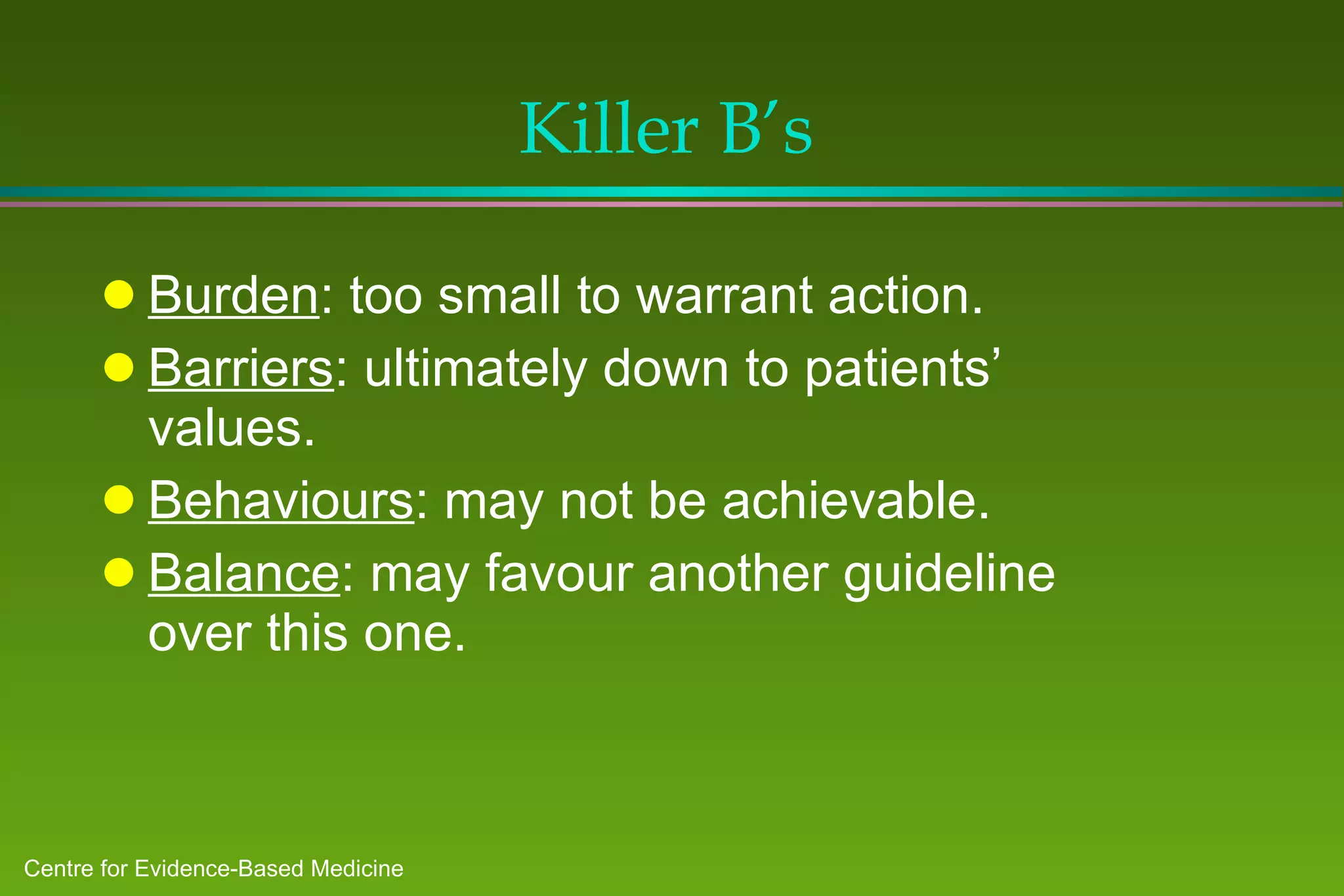

3) National clinical guidelines need local adaptation to consider unique patient populations, resources, behaviors and costs. Local groups are best equipped to identify

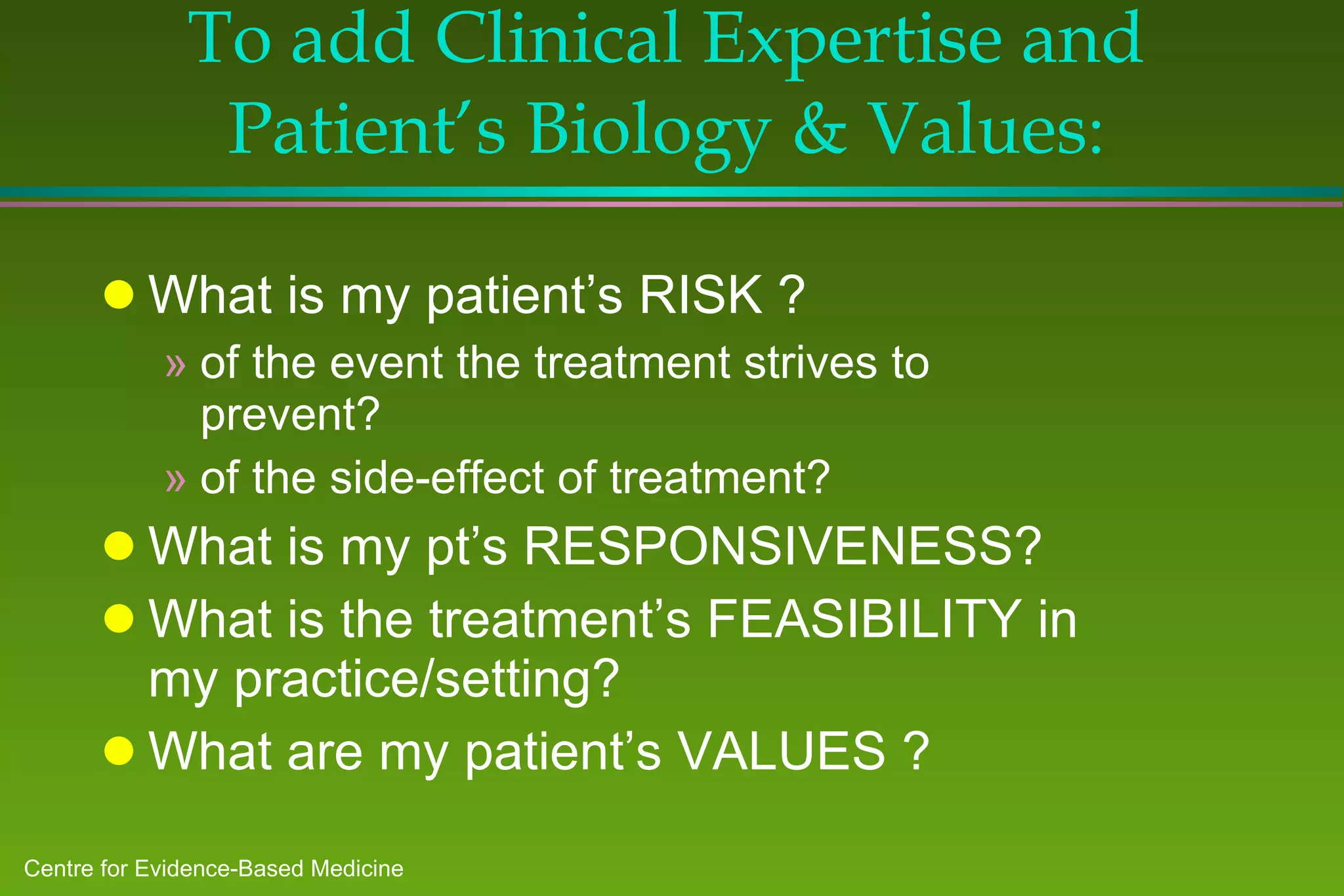

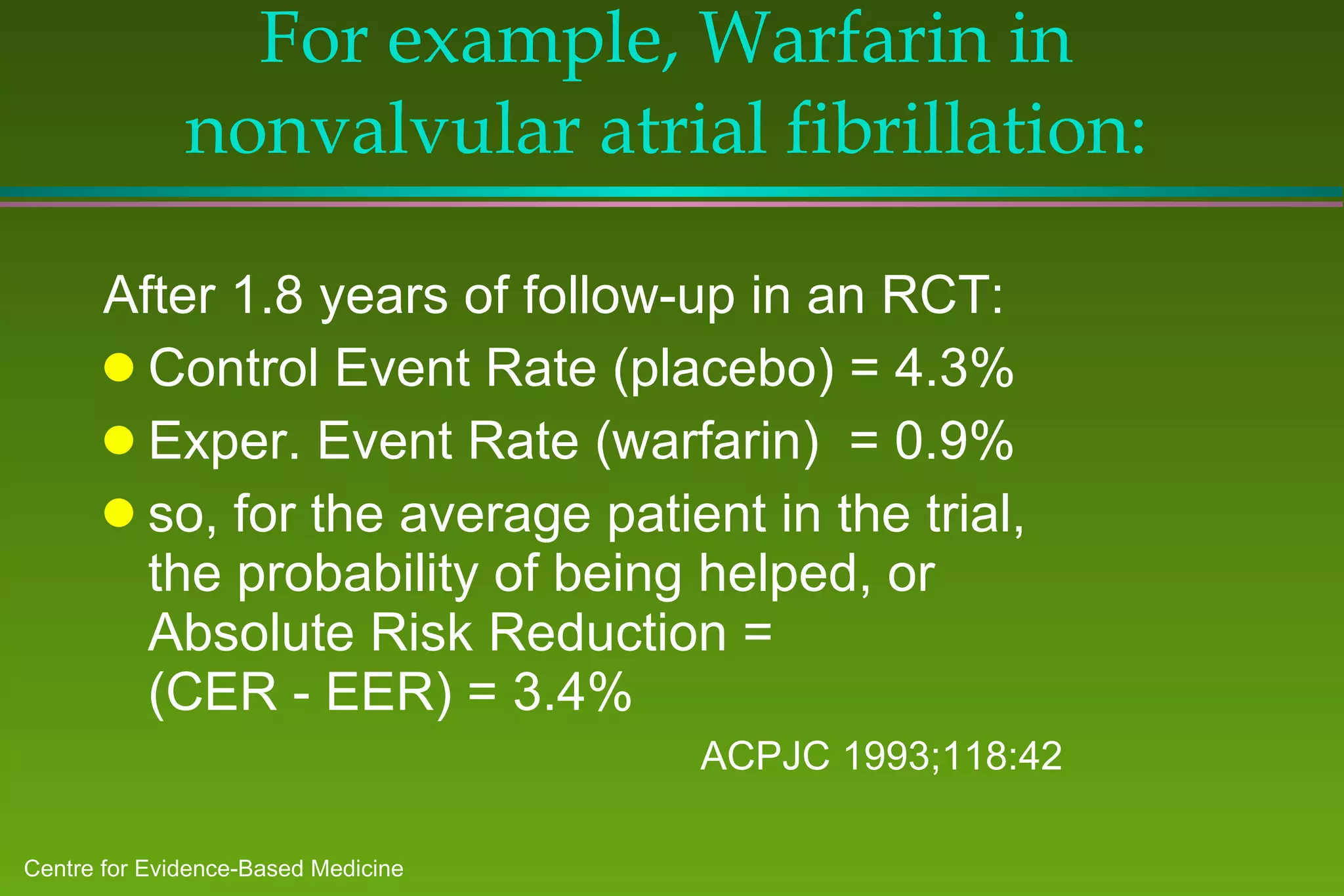

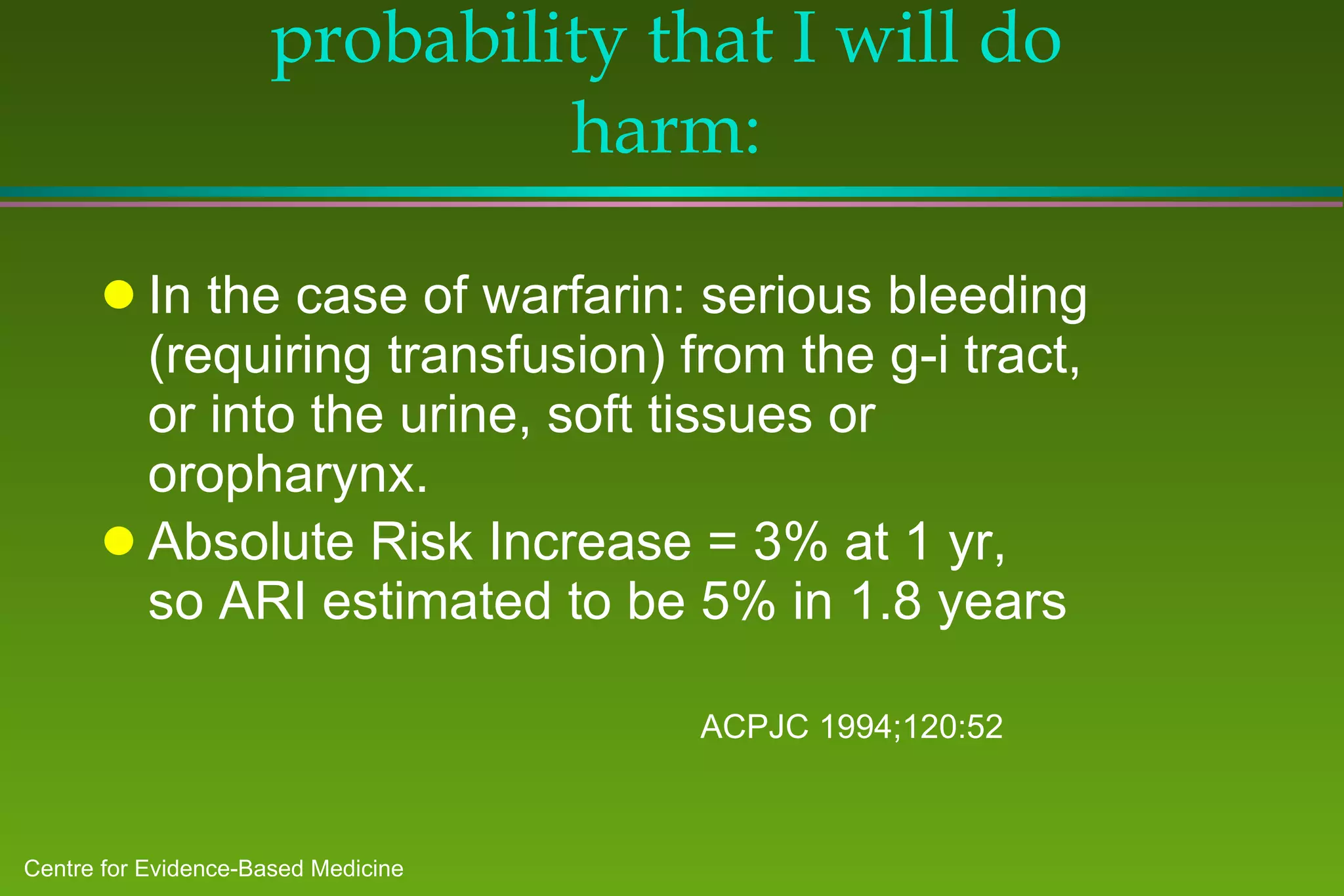

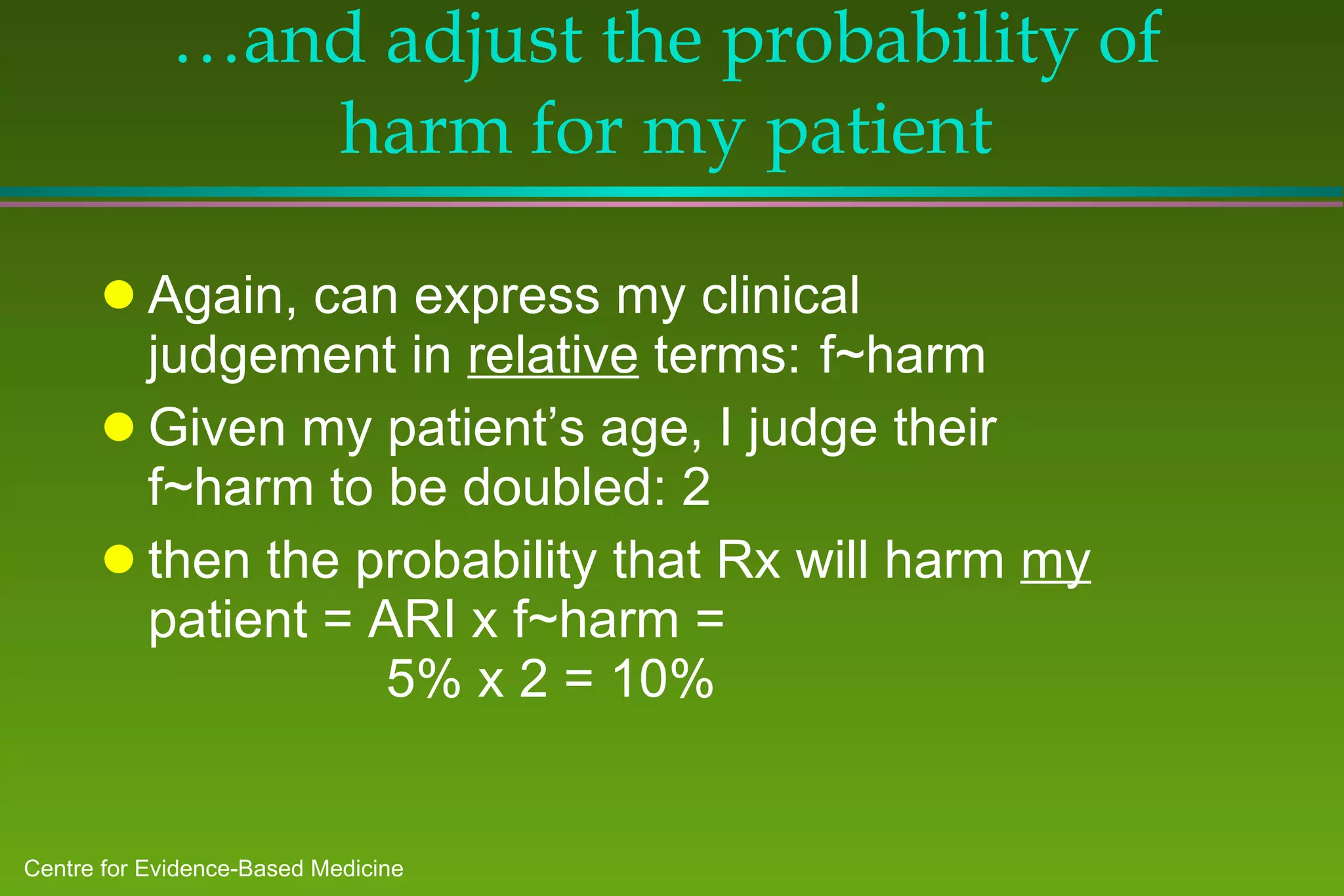

![To add Clinical Expertise and Patient’s Biology & Values : I begin by considering Risk and Responsiveness for the event I hope to prevent with the treatment: The report gives me (or I can calculate) an Absolute Risk Reduction [ARR] for the average patient in the trial. ARR = probability that Rx will help the average patient.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ebm-talk-general-mar99-ppt95-100704103613-phpapp01/75/Ebm-talk-general-mar99-ppt95-77-2048.jpg)

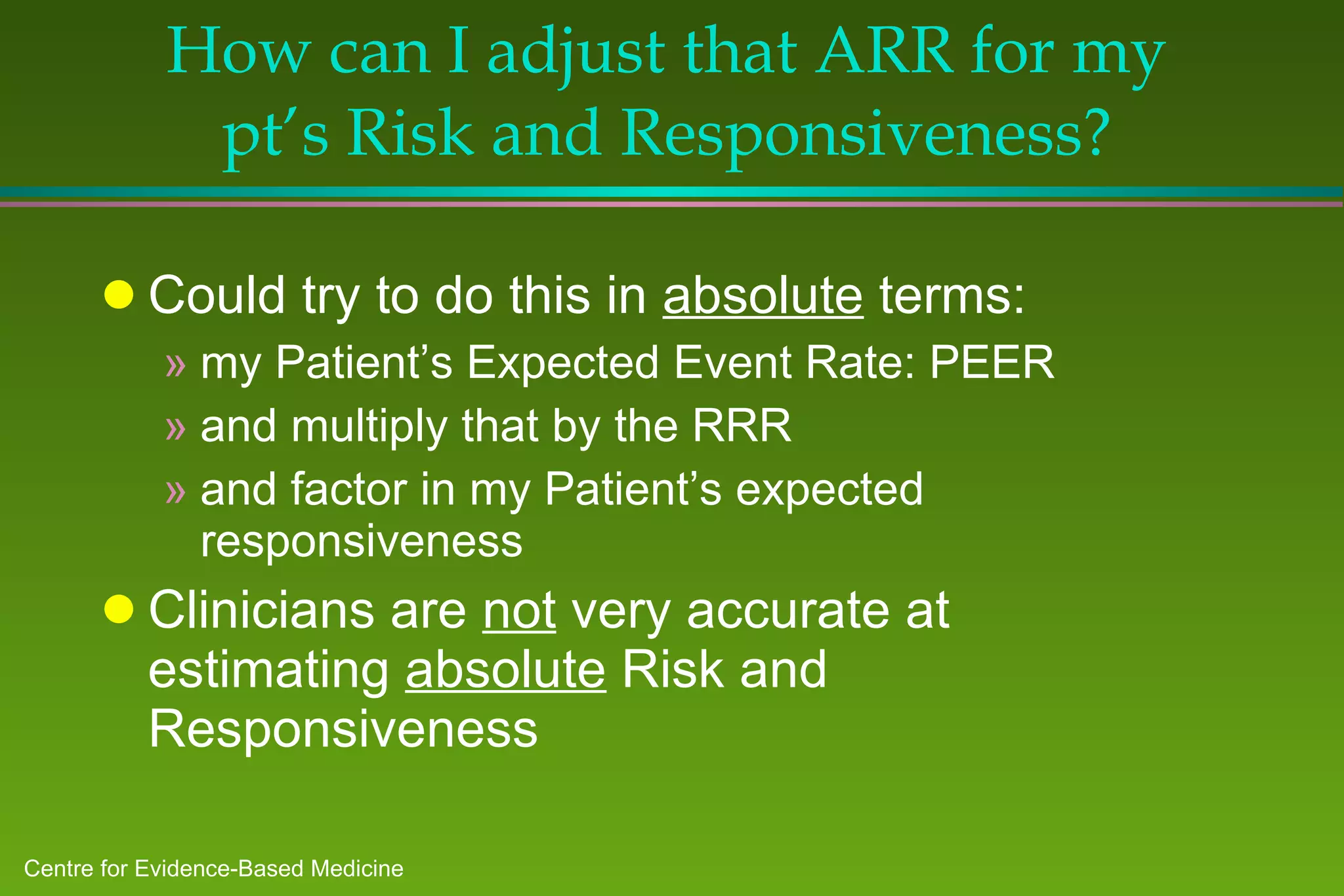

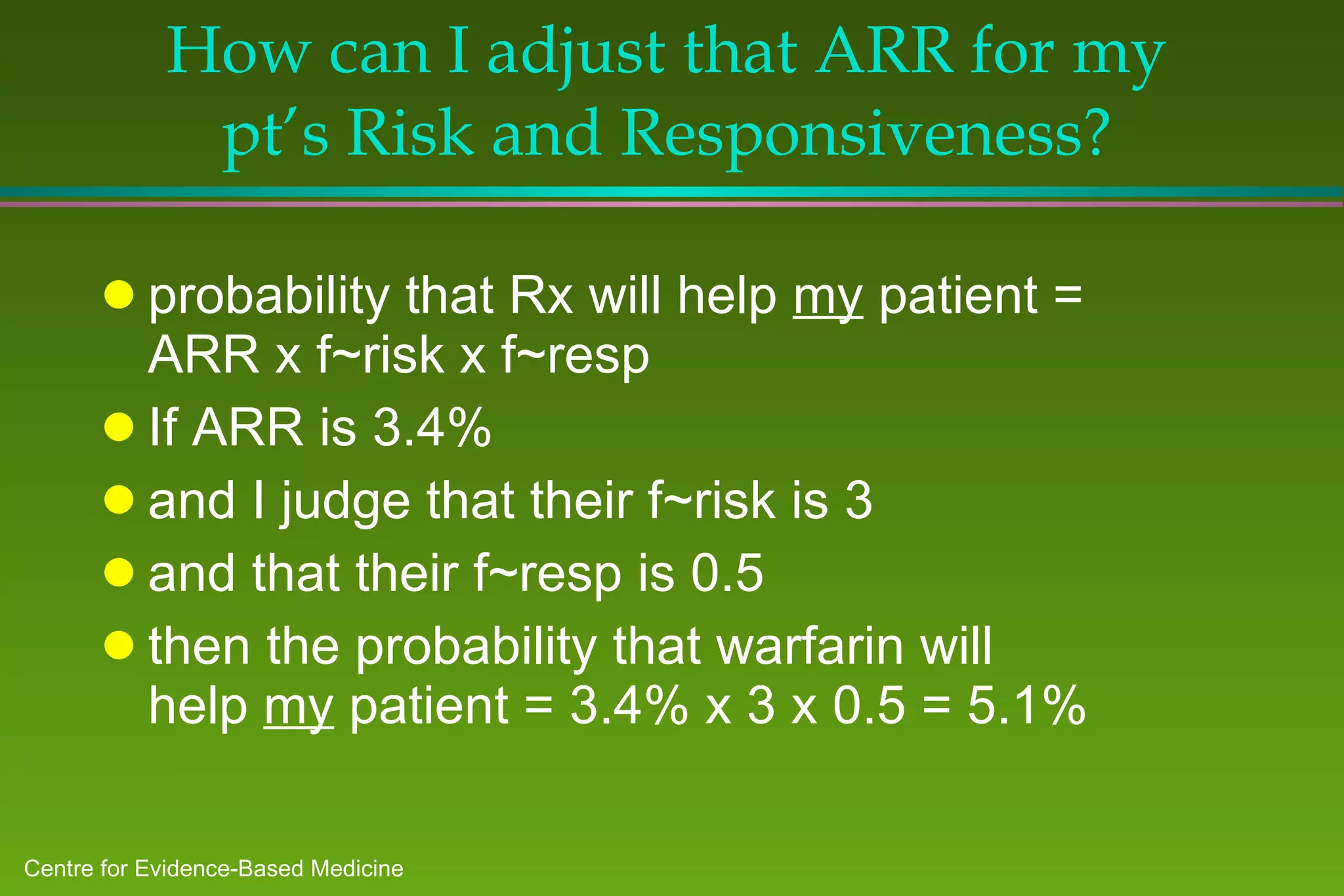

![How can I adjust that ARR for my pt’s Risk and Responsiveness? Clinicians are pretty good at estimating their patient’s relative Risk and Responsiveness So, I express them as decimal fractions: f~risk (if at three times the risk, f~risk = 3) f~resp (if only half as responsive [e.g., low compliance], f~resp = 0.5)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ebm-talk-general-mar99-ppt95-100704103613-phpapp01/75/Ebm-talk-general-mar99-ppt95-80-2048.jpg)

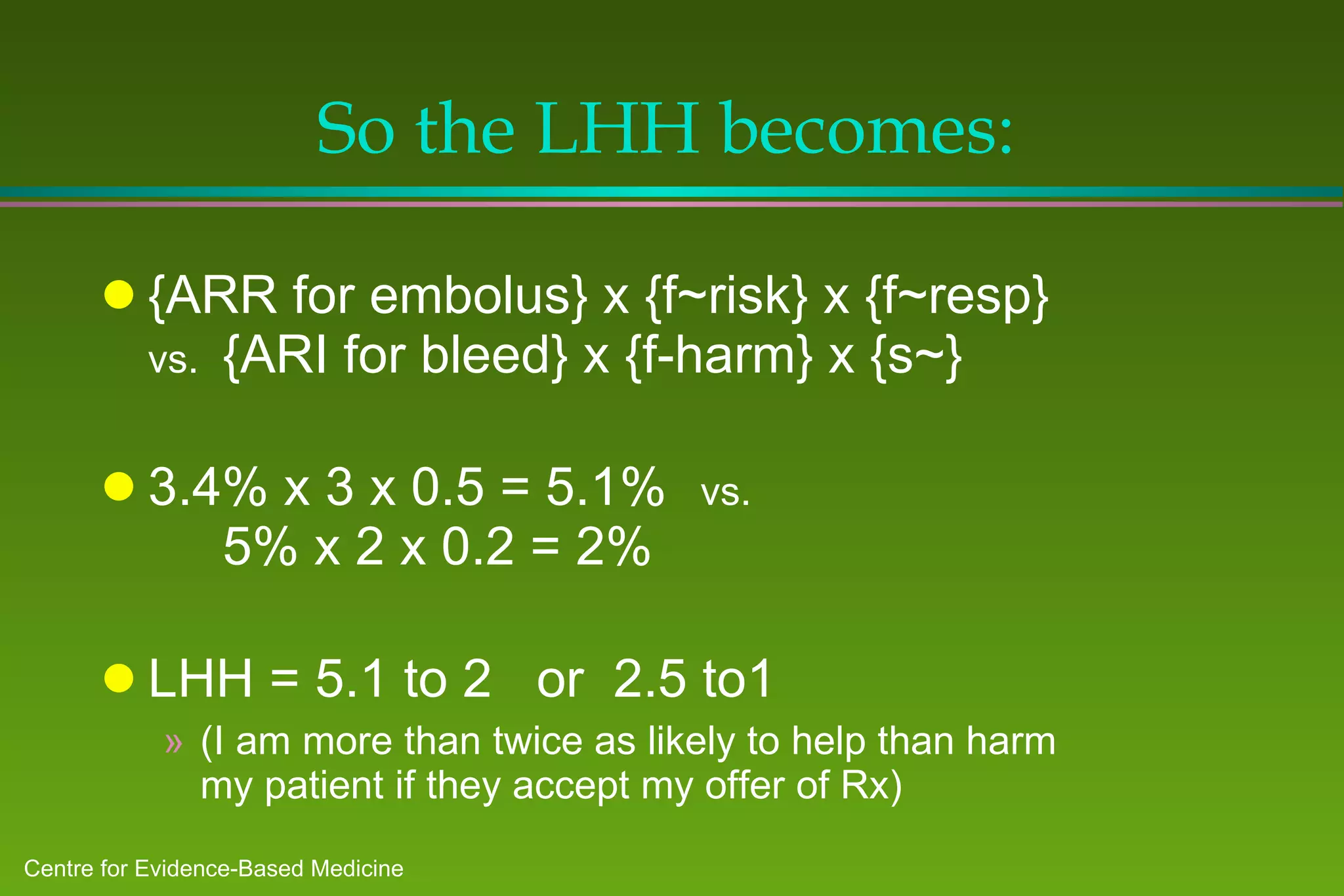

![Can now begin to estimate the Likelihood of Help vs. Harm Probability of help: ARR (embolus) x f~risk x f~resp = 5.1% Probability of harm: ARI (haemorrhage) x f~harm = 10% My patient’s Likelihood of Being Helped vs. Harmed [LHH] is: (5.1% to 10%) or 2 to 1 against warfarin! … or is it ?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ebm-talk-general-mar99-ppt95-100704103613-phpapp01/75/Ebm-talk-general-mar99-ppt95-84-2048.jpg)