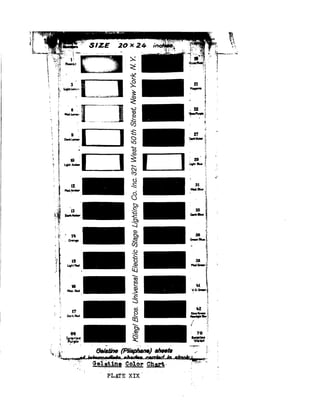

The document provides guidance for directors of music in senior high schools on producing effective musical programs. It discusses various types of programs, considerations for program building such as attention, contrast and continuity. Organization, administration, publicity, programs/tickets, staging, lighting, costuming and other elements are covered. Experimental research was conducted, including visits to Radio City Music Hall and small theaters, to study professional practices.

![I

PART ONE

HIGH SCHOOL ORCHESTRA

MARCH—Tannhauser ..................................................... Richard Wagner

Inspiring, dramatic and compelling, describes the music of the

master-composer who lived to have his music accepted after many

critics had been unsympathetic to the “weird noises.”

ADORATION Felix Borowski

Poetic beauty on wings of a melody of grandeur gives this se

lection its proper setting. Mr. Borowski was formerly director

of the Chicago Musical College. (Solo played by members of

the first violin section.)

PROCESSION OF THE SARDAR ............................ Ippolitow-Iwanow

Describes a procession of military officers, who in the days of

the Czar disclosed their high rank by surrounding themselves

with a train of brilliantly dressed followers from the Orient.

ALLEGRO FROM CONCERTO No. 2 3 ................................ G. B. Viotti

This very popular violin concerto although often played by

violinists and pianists is rarely heard in its original setting for

orchestra and solo violin.

Nelson Monical, violinist

HUNGARIAN DANCE No. 5 .................................... Johannes Brahms

The Hungarian Dance is exactly what the title indicates. Hun

garian themes that were put into the present shape by Brahms.

Many of them were of gypsy origin, but some were in the native

hungarian style, which does not show the gypsy scale. They

are invigorating!

HUMMING CHORUS FROM

Proving the exception Mr,

setting of the famous ins

present number was take

MY LORD WHAT A MOUR]

Charles

The spiritual is rapidly

of American music. Its

votion and demonstrativ

US

PART TWO

A CAPPELLA CHOIR

O BONE JESU ................................................ Giovanni P. Da Palestrina

The beauty of this number lies in its simplicity and directness

of message. Its sincere reverence and noble text.

OPEN OUR EYES .................................................... Will C. Macfarlane

Catherine Lynch, soloist

ALL IN THE APRIL EVENING.................................... Hugh Roberton

This simple tone picture by the famous choral adjudicator from

Seotland is a living example of his expressed philosophy of

music; namely that spirituality is the governing force of all

music.

BLESS THE LORD (O My Soul) ........................... Ippolitow-Iwanow

Words adapted from Psalm CIII: Verses 2, 3, 8, 13, 18.

VIOL

PERPETUM MOBILE (perp

AUTUMN, a modern descrip

Violins: Nelson Monical,

Vacillios Pavoglou. Pian

PA

COMBINED

Accompanists: La

CHORUS FROM “L’ALLEG

“Or Let the Merry Bells I

The gay spirit of this it

the great classicist Hand

A SNOW LEGEND ...........

Delicate, imaginative, ant

and thoughts with mast<

CREOLE SWING SONG ...

Mr. Denza has succeedet

that invites receptive lis

THE BIG BROWN BEAR (s:

OLD KING COLE

Traditional air with desc

character depicted is knc

natured personality.

II

THE FLIGHT OF THE BUI

From the opera “The Le

flight of a persistent ye

Norman Hadley, clarinetist

MUSIC BOX ..........................

Recalling the powder pui

instrument preceding th<

Norman Hadley, Warren I

R

PLAl](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sdewsdweddes-191208115857/85/Sdewsdweddes-168-320.jpg)

![151

TENORS

Donald Cohen, William Devine. Armando Di Mauro,

Ralph Dunham. George French, Walter Lewis. Nicholas

Morace.

BASSES

Donald Doyle. Sherman Greenberg, Ellery Jones. Alter,

Lan, Sidney I.annon, Paul Leavitt. Frank Mazza, George

Moller. Wendell Moore, Renzo Pasehetto, Isadora Rulniek.

RobeH Teeee. William Wilson.

GDrrljPstra PrraniittM

Violins: Mavion Reynolds, Howard Hurwitz, Vasileos

Pavlaglou, Edward Larson, Evelyn Barsom, Beatrice Dick

son, Anthony Mazza, Frank Kuczarski, Paul Gagnon, Crisso

Carranza, Michael Swedt, Muriel Loud, Mary O’Donnnell.

Viola: Philip Randall. Violoncello: George Sarandis. Dou

blebass: Dorothy Reynolds. Flute: Helen Kwajewski. Oboe:

Helen Berman. Clarinets: Virginia Dawes, William Foskit,

Wendell Love, William Moriarty. Bassoon: Catherine Pila-

las. Trumpets: Lawrence Donovan, Carol Ingram, Kenneth

Howe, Fred Winkley. French Horn: Edith Snow. Trom

bone: WTilliam D’Epagnier. Chimes: Pauline Phinney. Per

cussions: Harold Clinton. Tympani: Lawrence Dimetres.

Piano: Rachel Barsom.

Student accompanists: Girls’ Glee Club, Laura Sterns,

Rachel Barsom. Boys’ Glee Club, Sadie Glassanos.

Stage crew: Alton Nadeau, Raymond Camyre, Walrath

Beach, Alfred Shepherd.

I*

Violin Quintet: Howard Hurwitx, leader. Edward LaewJ*

aon, Marion Reynolds, Evelyn Barsom, Vasileos PavloglouTrT

Brass Sextet: Lawrence Donovan, leader and cometV'; •

to o l Ingram, comet. Edith Snow, French Horn. Dorothy,

Donnachie, William D’Epagnier, trombones. Margaret Tar**,

pinian, baritone.

Girls’ double trio: Rodha Bloomstein, Ruth Tovet, Ruth

Pehrsson, Mercedes Roberta, Marjorie Anderson, Martha^ ' a

Johnson. r '

1

Us]

Bracci,

Gauthie:

lette,

is great

our pet’

ic de

indeb

e

Muriel Guy, Mary Elisabeth Barhydt, Thereat

nor Cooley, Edna Cronin, Lucille Digeaaro, wiM f

"»ry Miller, Mary Naisternig, Lawrentine Ouel-

nith, Rita Stewart.

of the High School of Commerce

"iany who have aided in making

iduding:

the High School of Commerce.

*

, . Ol '0.;,

L. ^Bfces Tfeirtellotie—ushers

Beraf^-White-^-gowmi

Belding F. Jackson—Boys’ Patrol

Mr. Bert Cropley for use of chimes

Charles H. Oswald—stage s-..

Elbryn H. B. Myers—terraa|§F:

Gilbert Walker—tickets W

Lloyd H. Hayes . -

. ‘ The Everett Orgatron use# in this concert is furnished

through the courtesy of the local representative.

J. G. Heidner & Son, Inc.

93 State Street — Springfield, Mass.

PLATE XXXV](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sdewsdweddes-191208115857/85/Sdewsdweddes-177-320.jpg)