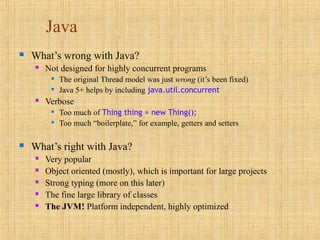

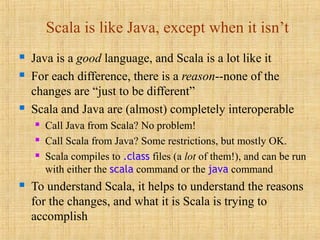

This document discusses Scala and its relationship to Java. Some key points:

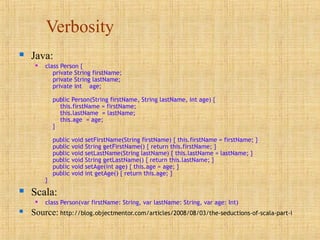

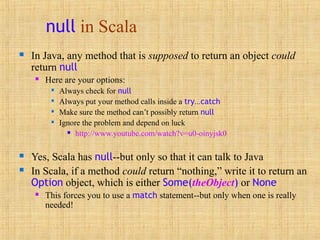

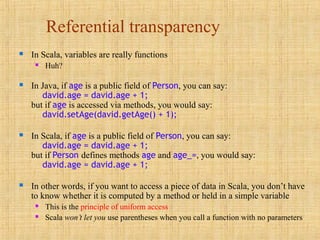

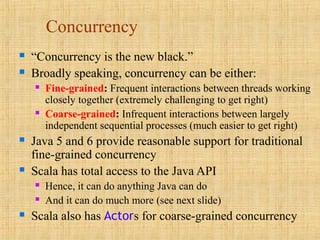

- Scala is largely compatible with Java but aims to address issues like verbosity and concurrency through functional programming concepts.

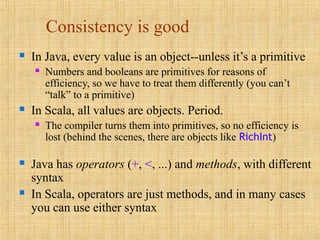

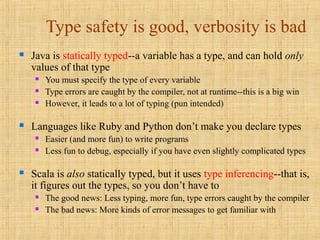

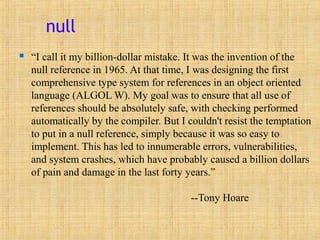

- Scala simplifies things like type declarations through type inference and makes all values objects to improve consistency.

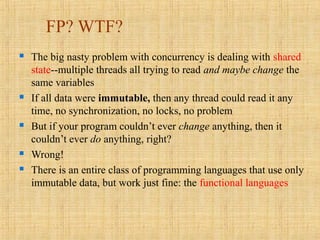

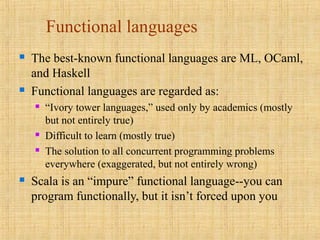

- Functional programming with immutable data makes concurrency easier by avoiding shared state issues, though Scala also supports object-oriented and imperative styles.

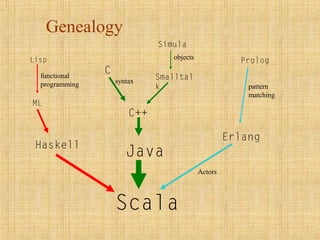

- Scala's goals include keeping the benefits of Java like performance and libraries while addressing weaknesses through influences from languages like ML, Haskell, Erlang and more.