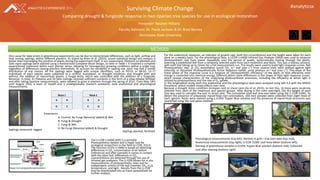

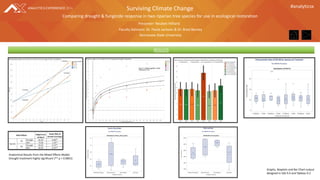

This document summarizes a study comparing the drought and fungicide responses of two riparian tree species, Salix nigra and Platanus occidentalis, for use in ecological restoration. Saplings of both species were subjected to control, drought, or drought with fungicide treatments in a greenhouse experiment using a randomized block design. Anatomical measurements of height and circumference were taken weekly, and physiological measurements of photosynthetic rates were taken using a LI-COR gas analyzer. Results showed Platanus grew faster than Salix under drought conditions based on anatomical data, while physiological data found Platanus responded better to light under drought. However, statistical analyses found no significant differences between species or treatments for most measurements