The document discusses the fundamental principles of quantitative research, focusing on validity and the importance of scientific merit. It highlights the ethical considerations in research involving human subjects as established in the Belmont Report, outlining key principles such as respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. The report emphasizes the necessity of ethical review processes and proper guidelines to ensure the integrity and reliability of research outcomes.

![3. Justice

• C. Applications

1. Informed Consent

2. Assessment of Risk and Benefits

3. Selection of Subjects

Ethical Principles & Guidelines for Research Involving Human

Subjects

Scientific research has produced substantial social benefits. It

has also posed some troubling ethical

questions. Public attention was drawn to these questions by

reported abuses of human subjects in

biomedical experiments, especially during the Second World

War. During the Nuremberg War Crime

Trials, the Nuremberg code was drafted as a set of standards for

judging physicians and scientists who

had conducted biomedical experiments on concentration camp

prisoners. This code became the prototype

of many later codes[1] intended to assure that research

involving human subjects would be carried out in

an ethical manner.

The codes consist of rules, some general, others specific, that](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-8-2048.jpg)

![[RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS]

Part A: Boundaries Between Practice & Research

A. Boundaries Between Practice and Research

It is important to distinguish between biomedical and behavioral

research, on the one hand, and the

practice of accepted therapy on the other, in order to know what

activities ought to undergo review for the

protection of human subjects of research. The distinction

between research and practice is blurred partly

because both often occur together (as in research designed to

evaluate a therapy) and partly because

notable departures from standard practice are often called

"experimental" when the terms "experimental"

and "research" are not carefully defined.

For the most part, the term "practice" refers to interventions

that are designed solely to enhance the well-

being of an individual patient or client and that have a

reasonable expectation of success. The purpose of

medical or behavioral practice is to provide diagnosis,

preventive treatment or therapy to particular

individuals [2]. By contrast, the term "research' designates an](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-10-2048.jpg)

![activity designed to test an hypothesis,

permit conclusions to be drawn, and thereby to develop or

contribute to generalizable knowledge

(expressed, for example, in theories, principles, and statements

of relationships). Research is usually

described in a formal protocol that sets forth an objective and a

set of procedures designed to reach that

objective.

When a clinician departs in a significant way from standard or

accepted practice, the innovation does not,

in and of itself, constitute research. The fact that a procedure is

"experimental," in the sense of new,

untested or different, does not automatically place it in the

category of research. Radically new procedures

of this description should, however, be made the object of

formal research at an early stage in order to

determine whether they are safe and effective. Thus, it is the

responsibility of medical practice

committees, for example, to insist that a major innovation be

incorporated into a formal research project

[3].

Research and practice may be carried on together when research

is designed to evaluate the safety and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-11-2048.jpg)

![One special instance of injustice results from the involvement

of vulnerable subjects. Certain groups, such

as racial minorities, the economically disadvantaged, the very

sick, and the institutionalized may

continually be sought as research subjects, owing to their ready

availability in settings where research is

conducted. Given their dependent status and their frequently

compromised capacity for free consent, they

should be protected against the danger of being involved in

research solely for administrative

convenience, or because they are easy to manipulate as a result

of their illness or socioeconomic

condition.

[1] Since 1945, various codes for the proper and responsible

conduct of human experimentation in

medical research have been adopted by different organizations.

The best known of these codes are the

Nuremberg Code of 1947, the Helsinki Declaration of 1964

(revised in 1975), and the 1971 Guidelines

(codified into Federal Regulations in 1974) issued by the U.S.

Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare Codes for the conduct of social and behavioral research

have also been adopted, the best known

being that of the American Psychological Association,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-34-2048.jpg)

![published in 1973.

[2] Although practice usually involves interventions designed

solely to enhance the well-being of a

particular individual, interventions are sometimes applied to

one individual for the enhancement of the

well-being of another (e.g., blood donation, skin grafts, organ

transplants) or an intervention may have the

dual purpose of enhancing the well-being of a particular

individual, and, at the same time, providing some

benefit to others (e.g., vaccination, which protects both the

person who is vaccinated and society

generally). The fact that some forms of practice have elements

other than immediate benefit to the

individual receiving an intervention, however, should not

confuse the general distinction between research

and practice. Even when a procedure applied in practice may

benefit some other person, it remains an

intervention designed to enhance the well-being of a particular

individual or groups of individuals; thus, it

is practice and need not be reviewed as research.

[3] Because the problems related to social experimentation may

differ substantially from those of

biomedical and behavioral research, the Commission

specifically declines to make any policy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-35-2048.jpg)

![T

S O

N E

X

P

E

R

IE

N

C

E

REVISÃO SISTEMÁTICA DE TEORIAS: UMA

FERRAMENTA PARA AVALIAÇÃO E

ANÁLISE DE TRABALHOS SELECIONADOS

REVISIÓN SISTEMÁTICA DE TEORÍAS: UNA

HERRAMIENTA PARA EVALUACIÓN Y

ANÁLISIS DE TRABAJOS SELECCIONADOS

1 Nurse. Associate Professor of the Collective Nursing

Department, School of Nursing, University of São Paulo. São

Paulo, SP, Brazil. [email protected]

2 Nurse. Student of the Masters in Nursing Program, School of

Nursing, University of São Paulo. Fellow of the State of São

Paulo research Foundation. São

Paulo, SP, Brazil. [email protected]

Received: 06/23/2010

Approved: 04/11/2011

Português / Inglês](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-37-2048.jpg)

![health care workers, in a clear and systemati c manner, the

advancements and limitati ons of health care studies and

practi ces that use the reviewed theories. This process pro-

motes de full development of undergraduate and gradu-

ate students.

Scienti sts have to demand more and more from the in-

sti tuti ons that conduct or register systemati c reviews, the

inclusion of theoreti cal reviews or reviews concerned with

the theoreti cal dimension of the empirical work, either

with a qualitati ve or quanti tati ve nature, or both.

Hardly ever have we found instruments available for

this type of review, prepared to handle designs of empiri-

cal research. Here we propose to conti nue and improve a

trend set in this sense, already used in the JBI, which also

shelters opinion studies and makes available instruments

to perform them.

1503

Systematic review of theories: a tool to evaluate and

analyze selected studies

Soares CB, Yonekura T

Rev Esc Enferm USP

2011; 45(6):1497-1503

www.ee.usp.br/reeusp/

REFERENCES

1. Annan K. A challenge to the world’s scienti sts [editorial].

Science [In-

ternet]. 2003 [cited 2010 May 30];299(5612):1485. Available](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-57-2048.jpg)

![from:

htt p://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/short/299/5612/1485

2. Kotzin S. Journal selecti on for Medline. In: 71th World

Library

and Informati on Congress: IFLA General Conference and

Coun-

cil “Libraries - A voyage of discovery”; 2005 Aug 4th - 18th;

Os-

lo, Norway [Internet]. Oslo; 2005 [cited 2010 June 3]. Available

from: htt p://www.ifl a.org/IV/ifl a71/Programme.htm

3. Casti el LD, Sanz-Valero J. Entre feti chismo e

sobrevivência:

o arti go cientí fi co é uma mercadoria acadêmica? Cad Saúde

Pública. 2007;23(12):3041-50.

4. Kuhn T. A estrutura das revoluções cientí fi cas. 7ª ed. São

Pau-

lo: Perspecti va; 2003.

5. Casti el LD, Póvoa EC. Medicina Baseada em Evidências:

“no-

vo paradigma assistencial e pedagógico”? Interface Comun

Saúde Educ. 2002;6(11):117-21.

6. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for

System-

ati c Reviews of Interventi ons Version 5.1.0 updated March

2011 [Internet]. Melbourne: The Cochrane Collaborati on;

2011 [cited 2011 June 10]. Available from: www.cochrane-

handbook.org

7. Booth A. Cochrane or cock-eyed? How should we conduct

sys-

temati c reviews of qualitati ve research? Paper presented at](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-58-2048.jpg)

![the Qualitati ve Evidence-Based Practi ce Conference, Taking a

Criti cal Stance, Coventry University; 2001 May 14-16 [Inter-

net]. [cited 2010 June 3]. Available from: htt p://www.leeds.

ac.uk/educol/documents/00001724.htm

8. Mendes KDS, Silveira RCCP, Galvão CM. Revisão integra-

ti va: método de pesquisa para a incorporação de evidên-

cias na saúde e na enfermagem. Texto Contexto Enferm.

2008;17(4):758-64.

9. Salum MJL, Queiroz VM, Soares CB. Pesquisa social em

saúde: lições gerais de metodologia – a elaboração do plano

de pesquisa como momento parti cular da trajetória teórico-

metodológica. In: Anais do 2º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciên-

cias Sociais e Saúde; 1999; São Paulo, Brasil.

10. Alves-Mazzotti AJ. O método nas ciências naturais e

sociais: pes-

quisa quanti tati va e qualitati va. 2ª ed. São Paulo: Pioneira;

1999.

11. Guzzo RA, Jackson SE, Katzell RA. Meta-analysis analysis.

Res

Organ Behav. 1987;9(3):407-42.

12. Lalande A. Vocabulário técnico e críti co da fi losofi a. 3ª

ed.

São Paulo: Marti ns Fontes; 1999.

13. Elliott KC, McKaughan DJ. How values in scienti fi c dis-

covery and pursuit alter theory appraisal. Philos Sci.

2009;76(5):598-611.

14. Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systemati c review

of

the use of theory in the design of guideline disseminati on](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-59-2048.jpg)

![and implementati on strategies and interpretati on of the re-

sults of rigorous evaluati ons. Implement Sci. 2010;5:14.

15. O’Connell KA. Theories used in nursing research on

smoking

cessati on. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2009;27(1):33-62.

16. Arana GAC. Use of theories and models on papers of a Lati

n-

American journal in public health, 2000 to 2004. Rev Saúde

Pública. 2007;41(6):963-9.

17. Almeida AH. Educação em saúde: análise do ensino na grad-

uação em enfermagem no estado de São Paulo [tese douto-

rado]. São Paulo: Escola de Enfermagem da Universidade de

São Paulo; 2009.

18. Campos CMS, Soares CB, Trapé CA, Buff ett e BR, Silva

TC. Ar-

ti culação teoria-práti ca e processo ensino-aprendizagem em

uma disciplina de Enfermagem em Saúde Coleti va. Rev Esc

Enferm USP. 2009;43(n.esp 2):1226-31.

19. Abrantes NA, Marti ns LM. A produção do conhecimento

cientí fi co: relação sujeito-objeto e desenvolvimento do pens-

amento. Interface Comun Saúde Educ. 2007;11(22):315-25.

20. Santos VC, Soares CB, Campos CMS. A relação trabalho-

saúde de enfermeiros do PSF no município de São Paulo.

Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2007;41(n.esp):777-81.

21. Mendes Gonçalves RB. Tecnologia e organização social das

práti cas de saúde: característi cas tecnológicas do processo

de trabalho na Rede Estadual de Centros de Saúde de São

Paulo. São Paulo: Hucitec; 1994.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-60-2048.jpg)

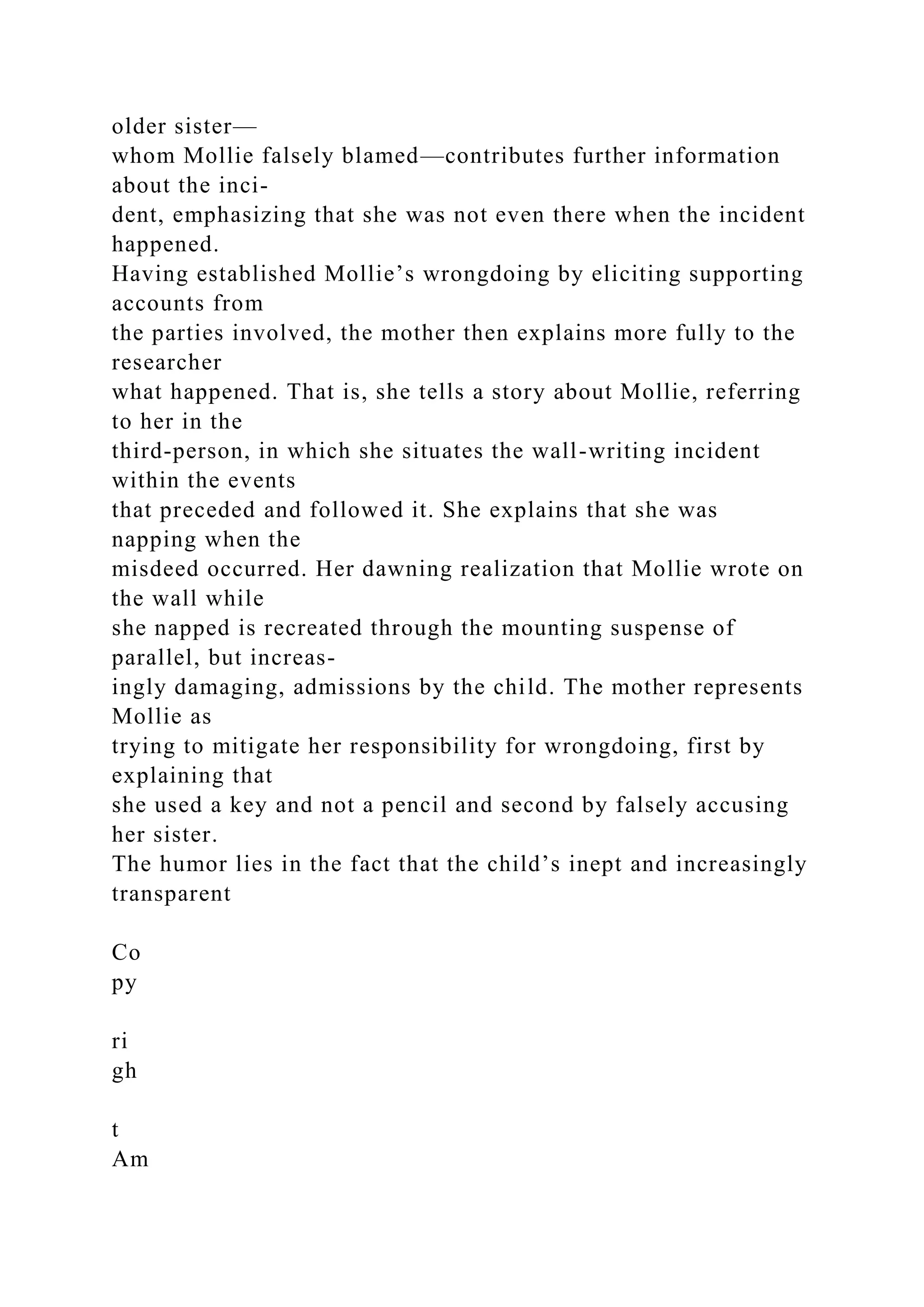

![Mother: [To child] Did you tell Judy [the researcher] what you

wrote on

the dining room wall with?

Child: Ah . . . key.

Researcher: [To child] You wrote on the dining room wall?

Mother: With a key, not even a pencil.

Researcher: [To mother] You must have loved that.

Mother: A key, the front end of that key.

Sister: And behind a living room chair.

Mother: I was sort of napping in there and I saw this and I

thought it was

a pencil. And I woke up and said [whispering], “Mol, you didn’t

write on

Mommy’s wall with a pencil, did you?” Oh, she was so relieved,

she said,

“No! Me no use pencil, me use key!” and I was like, “OH GOD!

Not a key!”

And she said, “No, no, ME no use key, Mom. Kara [her sister]

use key,” and

then I was even more upset.

Sister: I didn’t even see her do it!

Mother: But it’s so funny. You look at her and she’s like, “I

didn’t use pencil.”

Researcher: So, I’m in the clear.

Mother: Oh, yeah.

Sister: I didn’t even see her do it. I was at school.

In this excerpt, Mollie’s mother prompts her to confess her

wrongdoing to

the researcher. Mollie complies, and the researcher invites

additional response.

Several turns ensue in which the mother emphasizes that Mollie

used a key

to write on the wall, the researcher aligns herself with the

mother through an

ironic expression (“You must have loved that!”), and Mollie’s](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-110-2048.jpg)

![he

r

di

st

ri

bu

ti

on

.

Unit 3

[D]

INTRODUCTION

QUANTITATIVE TOOLS

Constructs

While substantial phenomena exist in the physical world and

can therefore be measured directly, insubstantial

phenomena exist in a symbolic or abstract form and cannot be

measured directly. Insubstantial phenomena are

frequently called constructs. You can think of a construct as a

scientific concept or an abstraction designed to

explain a natural phenomenon (Kerlinger, 1986). Constructs

allow us to talk about abstract ideas. The following

are examples of constructs:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-158-2048.jpg)

![expected to:

1. Identify variables in a research study.

2. Delineate quantitative instruments used to measure variables.

3. Explain the importance of operational definitions to scientific

merit.

4. Evaluate the data collection method or methods.

[u03s1] Unit 3 Study 1

STUDIES

Readings

Read the introduction to Unit 3, "The Tools of Research." This

will provide basic explanations and examples

of the key components of quantitative and qualitative research.

Use your Leedy and Ormrod text to complete the following:

• Read Chapter 1, "The Nature and Tools of Research,"

beginning with page 7 at the heading "Tools

for Research," through page 25. This reading covers some of the

tangible tools researchers use, such

as libraries and computers, as well as "cognitive tools," such as

critical thinking and logic.

• Read Chapter 8, "Analyzing Quantitative Data," pages 211–

250. This chapter reviews the types of

quantitative data, descriptive statistics, and inferential

statistics.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-168-2048.jpg)

![Review 14(4), 532–550. This article provides an overall process

and structure for case study research.

Probably the most cited case study methods paper in business

and management papers.

[u03s2] Unit 3 Study 2

PROJECT PREPARATION

Resources

Research Topic and Methodology Form.

Research Topic and Methodology Scoring Guide.

In preparation for the Unit 4 assignment due next week, make

sure during this unit that you have thoroughly

read and understand the approved research study you selected

for the Unit 2 assignment. Be prepared to

complete the Unit 4 assignment by identifying and

understanding the research topic, research problem,

research question, and basic methodology. You may also find it

beneficial to view the Research Topic and

Methodology Form that you will use to complete the Unit 4

assignment. Also, view the assignment

description and scoring guide to learn how you will be

evaluated.

QUANTITATIVE TOOLS

Resources](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/runningheadquantitativeresearch1quantitativeresearch3-221106025854-7497603d/75/Running-Head-Quantitative-research1Quantitative-research3-docx-171-2048.jpg)