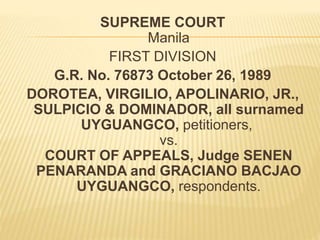

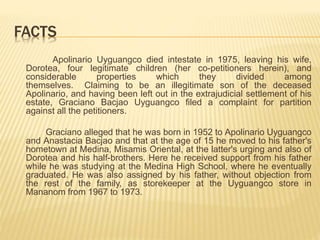

The Supreme Court ruled that Graciano could no longer prove he was the illegitimate child of Apolinario under the Civil Code since Apolinario had passed away. However, the new Family Code allowed illegitimate children to prove filiation in the same way as legitimate children. While Graciano could no longer present evidence of his status during Apolinario's lifetime as required, the Court expressed hope the parties would reach an equitable agreement to allow Graciano a share of the estate, given his prima facie proof of filiation. The complaint for partition was dismissed.