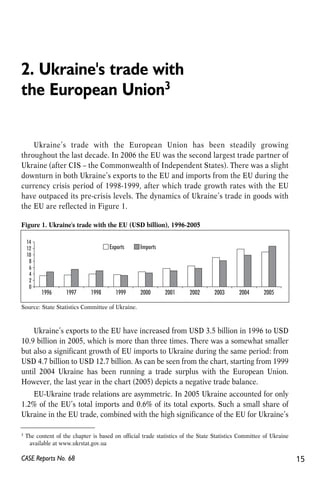

This document discusses Ukraine's trade policy and relations with the EU. It provides an overview of Ukraine's trade liberalization since the 1990s and its various trade agreements, including forming free trade areas with CIS countries and bilateral agreements. Ukraine applied to join the WTO in 1993 but negotiations were stalled until 2000. A key focus is Ukraine's economic relations with the EU, which have intensified in recent years following Ukraine's independence and EU enlargement in 2004. The EU is now Ukraine's major trading partner. The document examines trade flows between Ukraine and the EU and serves as context for the discussion of non-tariff barriers faced by Ukrainian exporters to the EU in subsequent chapters.