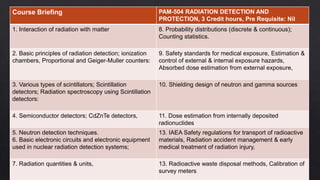

The document provides an overview of a course on radiation detection and protection. It discusses topics like the interaction of radiation with matter, basic principles of radiation detection using devices like ionization chambers and scintillation detectors. It also covers radiation quantities and units, shielding design, dose estimation from internal and external radiation exposures, transportation and disposal of radioactive materials, and safety standards.