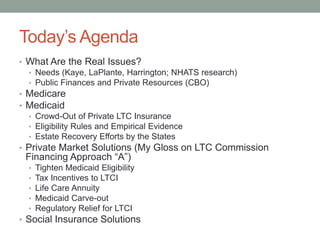

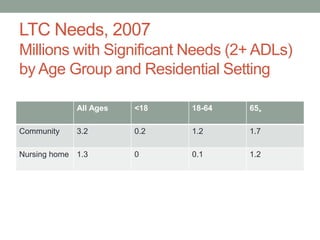

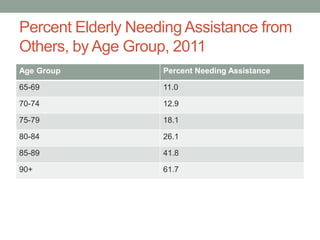

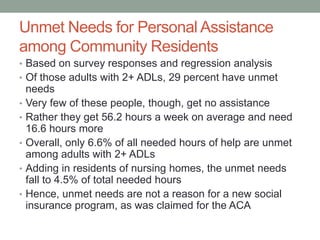

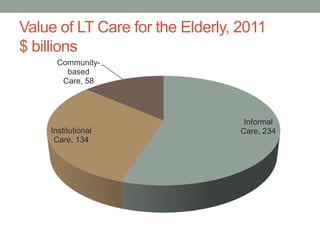

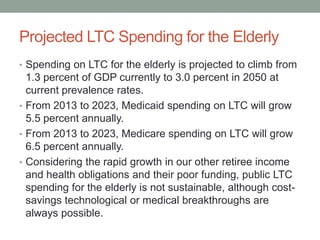

This document summarizes key issues regarding public and private financing of long-term care for the elderly. It discusses the growing needs and costs of long-term care, the limitations of current public programs like Medicaid and Medicare, and challenges facing the private long-term care insurance market. It also reviews various proposals to strengthen private market solutions or implement social insurance programs to better address long-term care financing issues in the future.