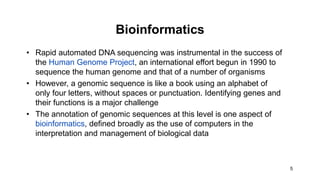

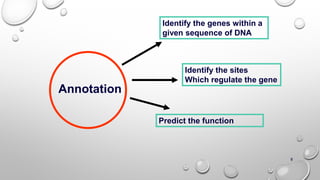

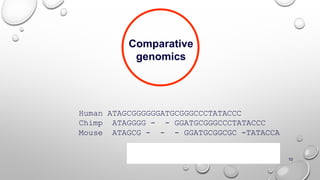

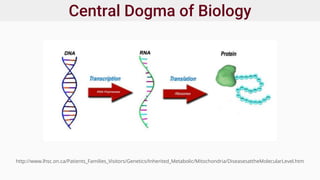

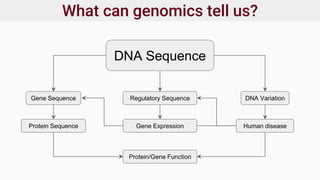

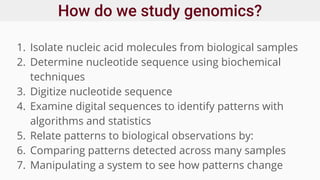

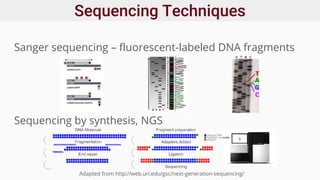

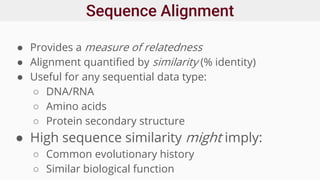

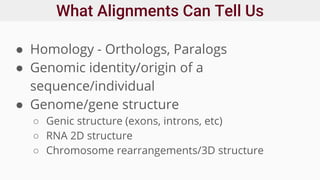

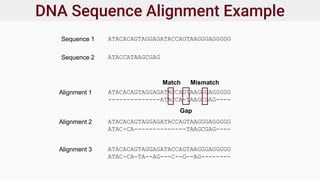

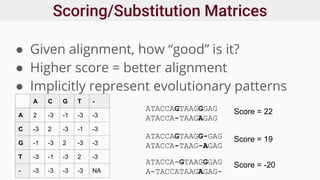

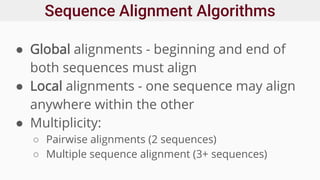

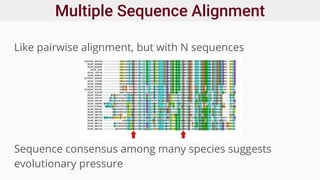

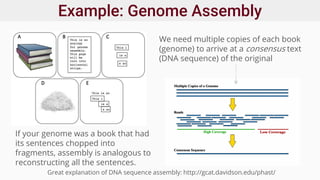

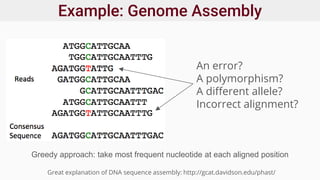

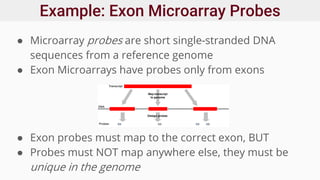

Genomics and proteomics are fields that study genomes and proteins. Genomics deals with DNA sequences and organization, while proteomics aims to identify all proteins in a cell including modified forms and interactions. Genetic engineering techniques like gene cloning were enabled by recombinant DNA techniques. These allow DNA fragments to be inserted into vectors and isolated using restriction enzymes. Reverse transcriptase can synthesize cDNA from mRNA. Bioinformatics helps with tasks like genome annotation and sequence alignment and comparison.

![Origin of “Genomics”: 1987

“For the newly developing discipline of [genome] mapping/sequencing

(including the analysis of the information), we have adopted the term

GENOMICS… The new discipline is born from a marriage of molecular and cell

biology with classical genetics and is fostered by computational science.”

- McKusick and Ruddle, A new discipline, a new name, a new journal,

Genomics, Vol. 1, No. 1. (September 1987), pp. 1-2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/proteome-231222193359-968db1e0/85/proteome-pdf-15-320.jpg)

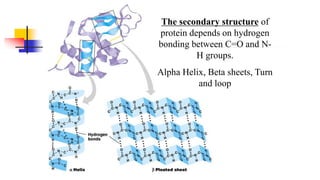

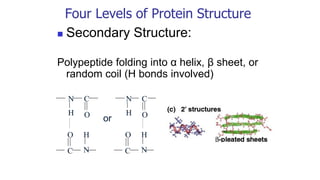

![Secondary structure of proteins - helix

H bond between the N-H of every peptide bond to the C=O of the next peptide bond of the

same chain. R groups are not involved.

(e.g. in protein -keratin - abundant in skin, hair, nails and horns)

[Fig. 4-10, p. 128]

(Pitch)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/proteome-231222193359-968db1e0/85/proteome-pdf-86-320.jpg)

![Secondary structure of proteins – β sheet

Polypeptide chains are held together by H bonds between N-H group of one polypeptide chain

and C=O group of the other chain

(e.g. in the protein fibroin - abundant in silk) [Fig. 4-10, p. 128]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/proteome-231222193359-968db1e0/85/proteome-pdf-87-320.jpg)

![helices can wrap around one another by interactions between their

hydrophobic side chains to form a stable coiled-coil. [Fig. 4-16]

e.g. keratin in the skin and myosin in muscles](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/proteome-231222193359-968db1e0/85/proteome-pdf-88-320.jpg)

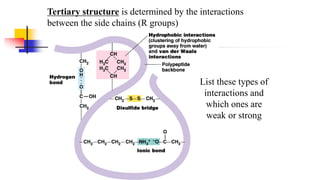

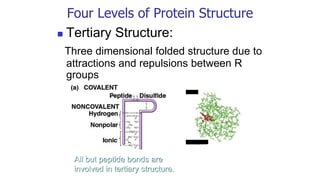

![Covalent disulfide bonds between adjacent cysteine side chains

help stabilize a favored protein conformation [Fig. 4-29]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/proteome-231222193359-968db1e0/85/proteome-pdf-93-320.jpg)

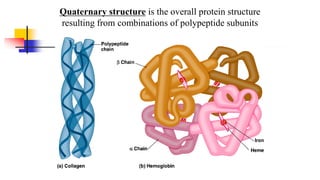

![Quaternary structure of proteins:

hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells, has

four sub units (two copies each of - and β-

globins containing a heme molecule [Fig. 4-23].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/proteome-231222193359-968db1e0/85/proteome-pdf-96-320.jpg)