This document discusses various techniques for optimizing Python code, including:

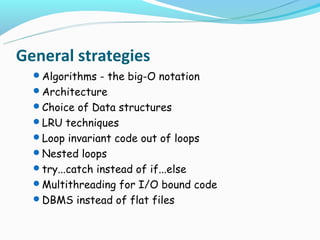

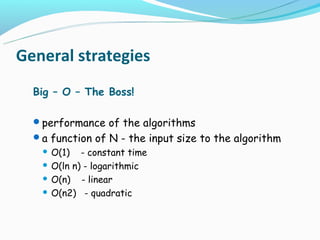

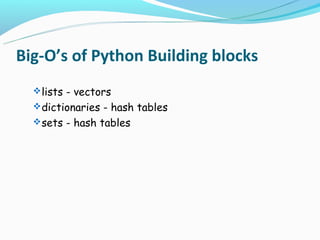

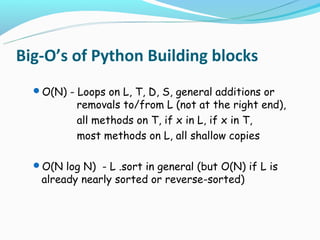

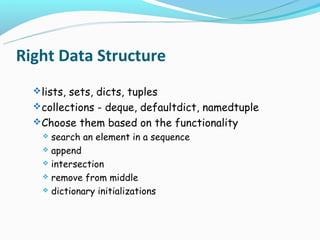

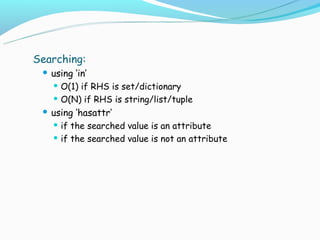

1. Using the right algorithms and data structures to minimize time complexity, such as choosing lists, sets or dictionaries based on needed functionality.

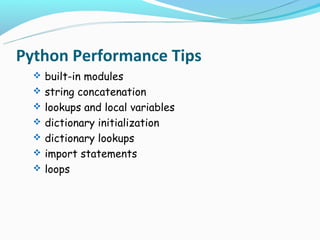

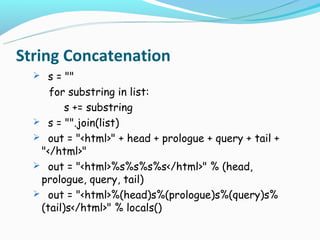

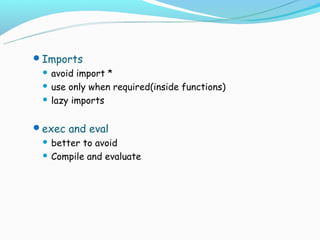

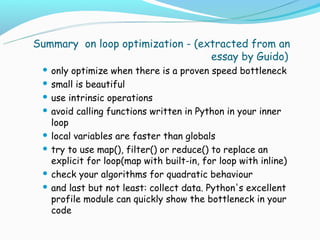

2. Leveraging Python-specific optimizations like string concatenation, lookups, loops and imports.

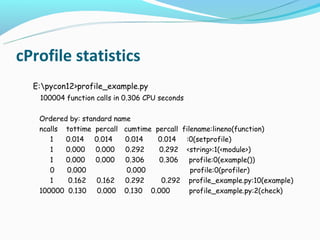

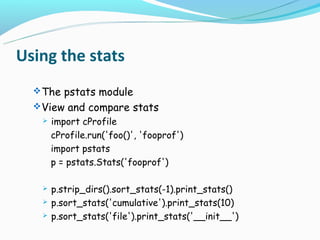

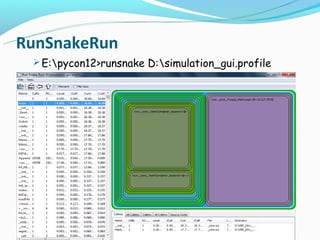

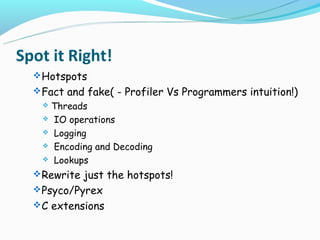

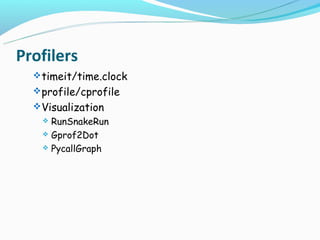

3. Profiling code with tools like timeit, cProfile and visualizers to identify bottlenecks before optimizing.

4. Optimizing only after validating a performance need and starting with general strategies before rewriting hotspots in Python or other languages. Premature optimization can complicate code.

![Common big-O’s

Order Said to be Examples

“…. time”

--------------------------------------------------

O(1) constant key in dict

dict[key] = value

list.append(item)

O(ln n) logarithmic Binary search

O(n) linear item in sequence

str.join(list)

O(n ln n) list.sort()

O(n2) quadratic Nested loops (with constant time bodies)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-12-320.jpg)

![Note the notation

O(N2) O(N)

def slow(it): def fast(it):

result = [] result = []

for item in it: for item in it:

result.insert(0, item) result.append(item)

return result result.reverse( )

return result

result = list(it)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-13-320.jpg)

![Big-O’s of Python Building blocks

Let, L be any list, T any string (plain or Unicode); D

any dict; S any set, with (say) numbers as items

(with O(1) hashing and comparison) and x any

number:

O(1) - len( L ), len(T), len( D ), len(S), L [i],

T [i], D[i], del D[i], if x in D, if x in S,

S .add( x ), S.remove( x ), additions or

removals to/from the right end of L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-15-320.jpg)

![Right Data Structure

my_list = range(n)

n in my_list

my_list = set(range(n))

n in my_list

my_list[start:end] = []

my_deque.rotate(-end)

for counter in (end-start):

my_deque.pop()](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-18-320.jpg)

![Right Data Structure

s = [('yellow', 1), ('blue', 2), ('yellow', 3), ('blue', 4), ('red', 1)]

d = defaultdict(list)

for k, v in s:

d[k].append(v)

d.items()

[('blue', [2, 4]), ('red', [1]), ('yellow', [1, 3])]

d = {}

for k, v in s:

d.setdefault(k, []).append(v)

d.items()

[('blue', [2, 4]), ('red', [1]), ('yellow', [1, 3])]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-19-320.jpg)

![Built-ins

- Highly optimized

- Sort a list of tuples by it’s n-th field

def sortby(somelist, n):

nlist = [(x[n], x) for x in somelist]

nlist.sort()

return [val for (key, val) in nlist]

n = 1

import operator

nlist.sort(key=operator.itemgetter(n))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-21-320.jpg)

![Loops:

list comprehensions

map as for loop moved to c – if the body of the loop is a

function call

newlist = []

for word in oldlist:

newlist.append(word.upper())

newlist = [s.upper() for s in oldlist]

newlist = map(str.upper, oldlist)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-24-320.jpg)

![Lookups and Local variables:

evaluating function references in loops

accessing local variables vs global variables

upper = str.upper

newlist = []

append = newlist.append

for word in oldlist:

append(upper(word))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-25-320.jpg)

![Dictionaries

Initialization -- try... Except

Lookups -- string.maketrans

Regular expressions:

RE's better than writing a loop

Built-in string functions better than RE's

Compiled re's are significantly faster

re.search('^[A-Za-z]+$', source)

x = re.compile('^[A-Za-z]+$').search

x(source)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-26-320.jpg)

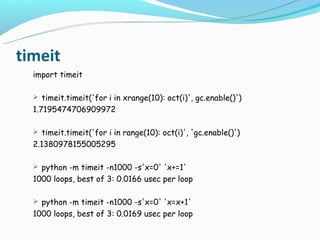

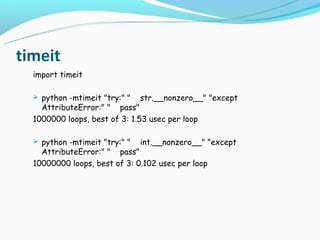

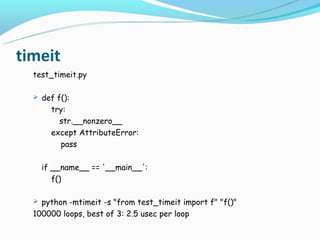

![timeit

precise performance of small code snippets.

the two convenience functions - timeit and repeat

timeit.repeat(stmt[, setup[, timer[, repeat=3[,

number=1000000]]]])

timeit.timeit(stmt[, setup[, timer[, number=1000000]]])

can also be used from command line

python -m timeit [-n N] [-r N] [-s S] [-t] [-c] [-h]

[statement ...]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-32-320.jpg)

![cProfile/profile

Deterministic profiling

The run time performance

With statistics

Small snippets bring big changes!

import cProfile

cProfile.run(command[, filename])

python -m cProfile myscript.py [-o output_file] [-s

sort_order]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/profilingandoptimization-120929002305-phpapp02/85/Profiling-and-optimization-36-320.jpg)