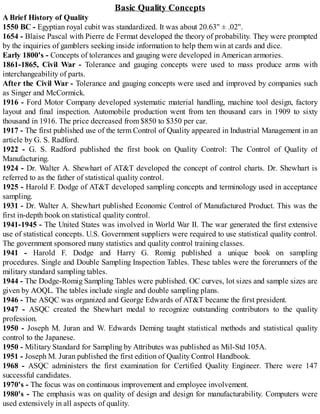

This document provides an overview of production and operations management topics for students pursuing a BBA degree from MGS University in Bikaner, India. It covers key POM concepts like different types of production systems, forecasting, capacity planning, plant layout, inventory management, quality management, and maintenance. The document also discusses the functions and scope of POM, relationships with other business functions, and differences between manufacturing and service operations. It is intended to help students with the theoretical concepts for their POM coursework.