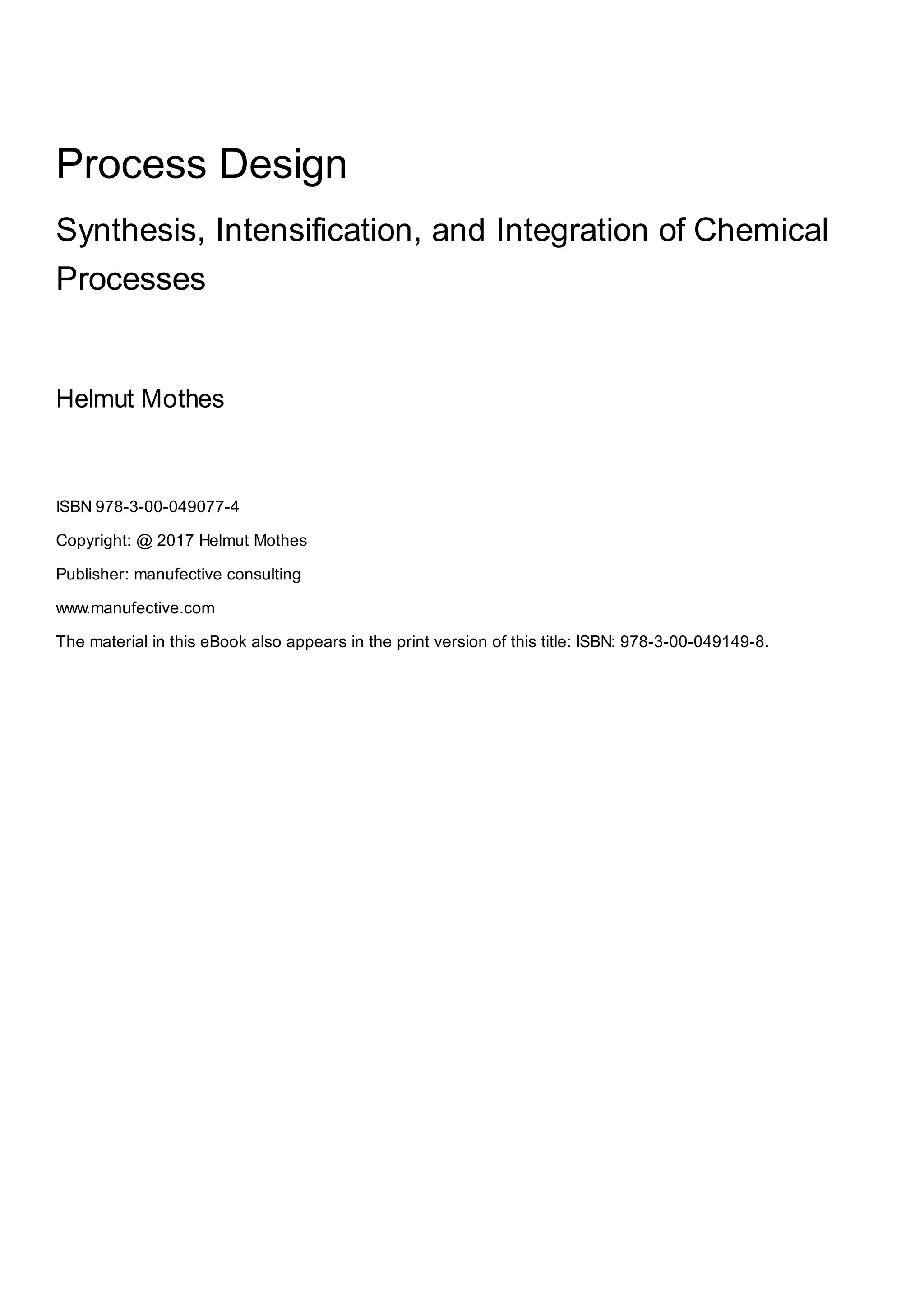

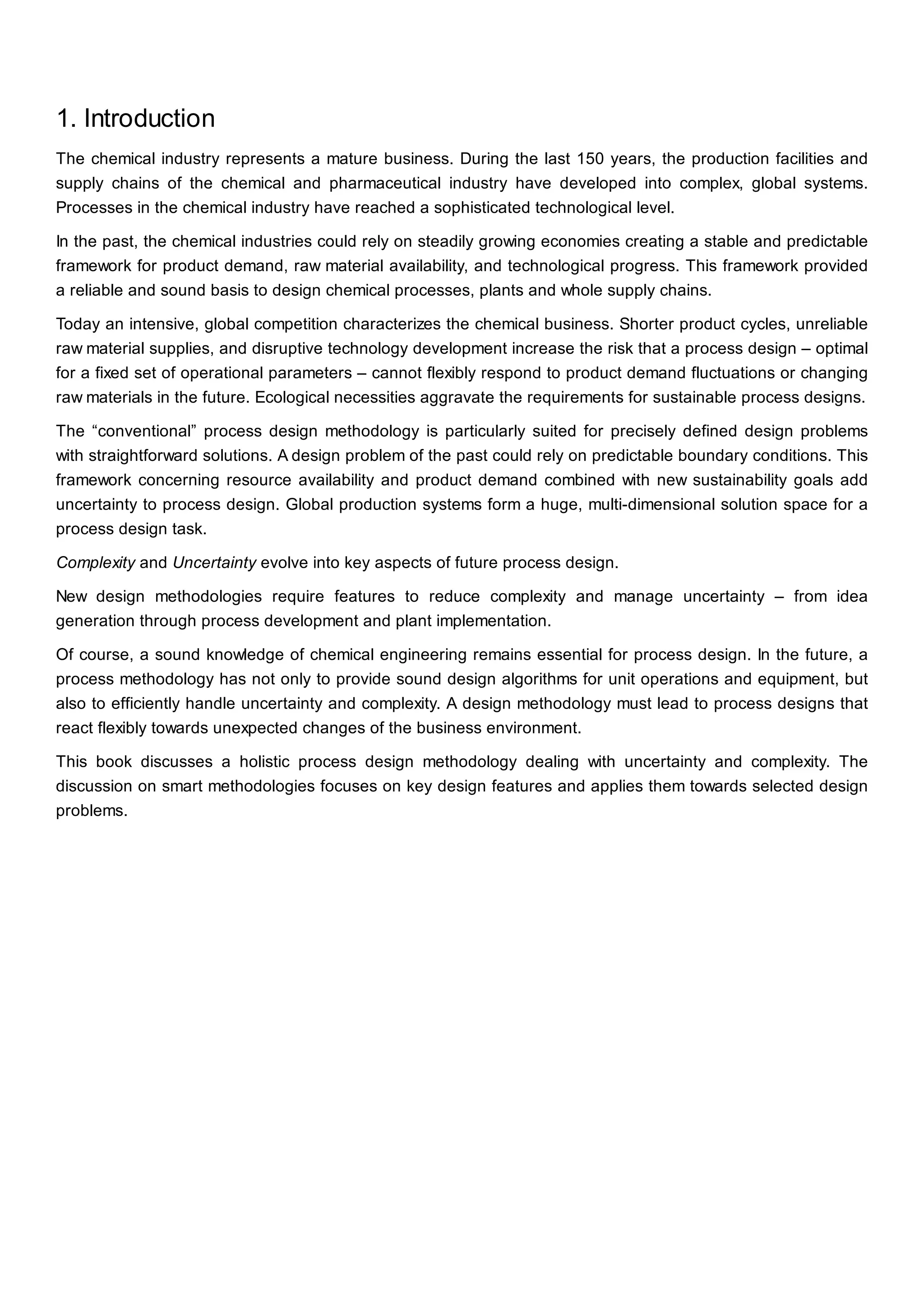

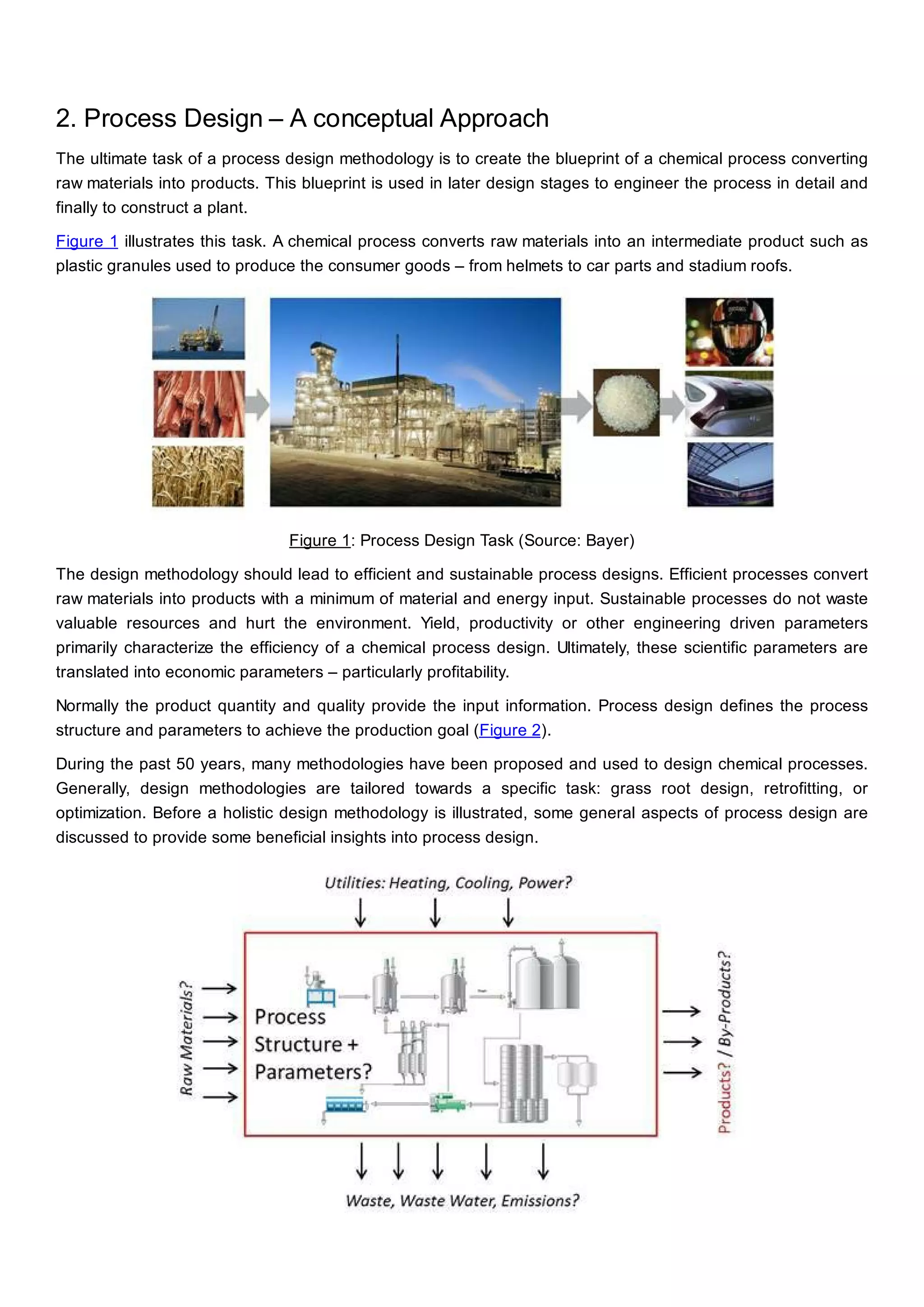

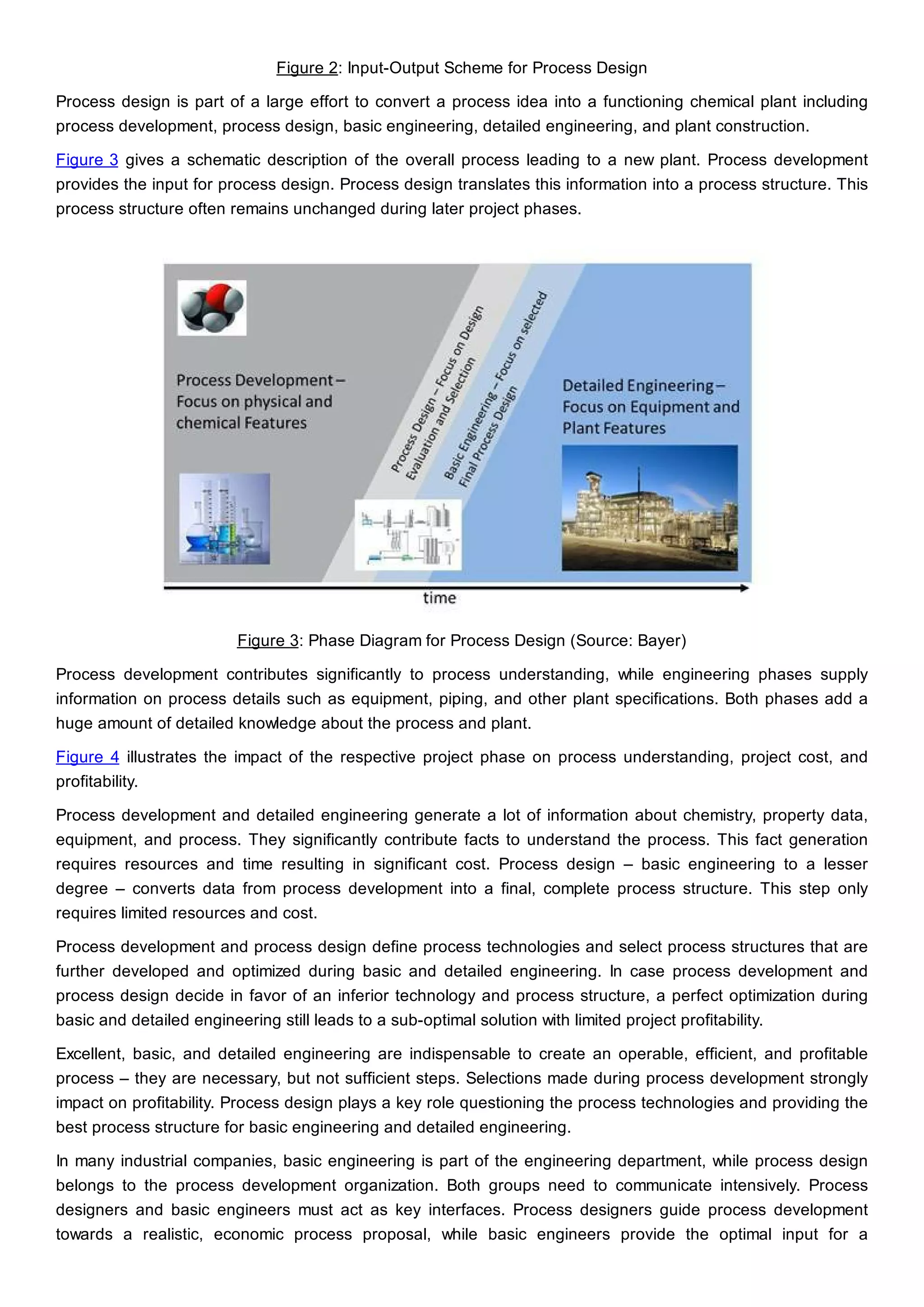

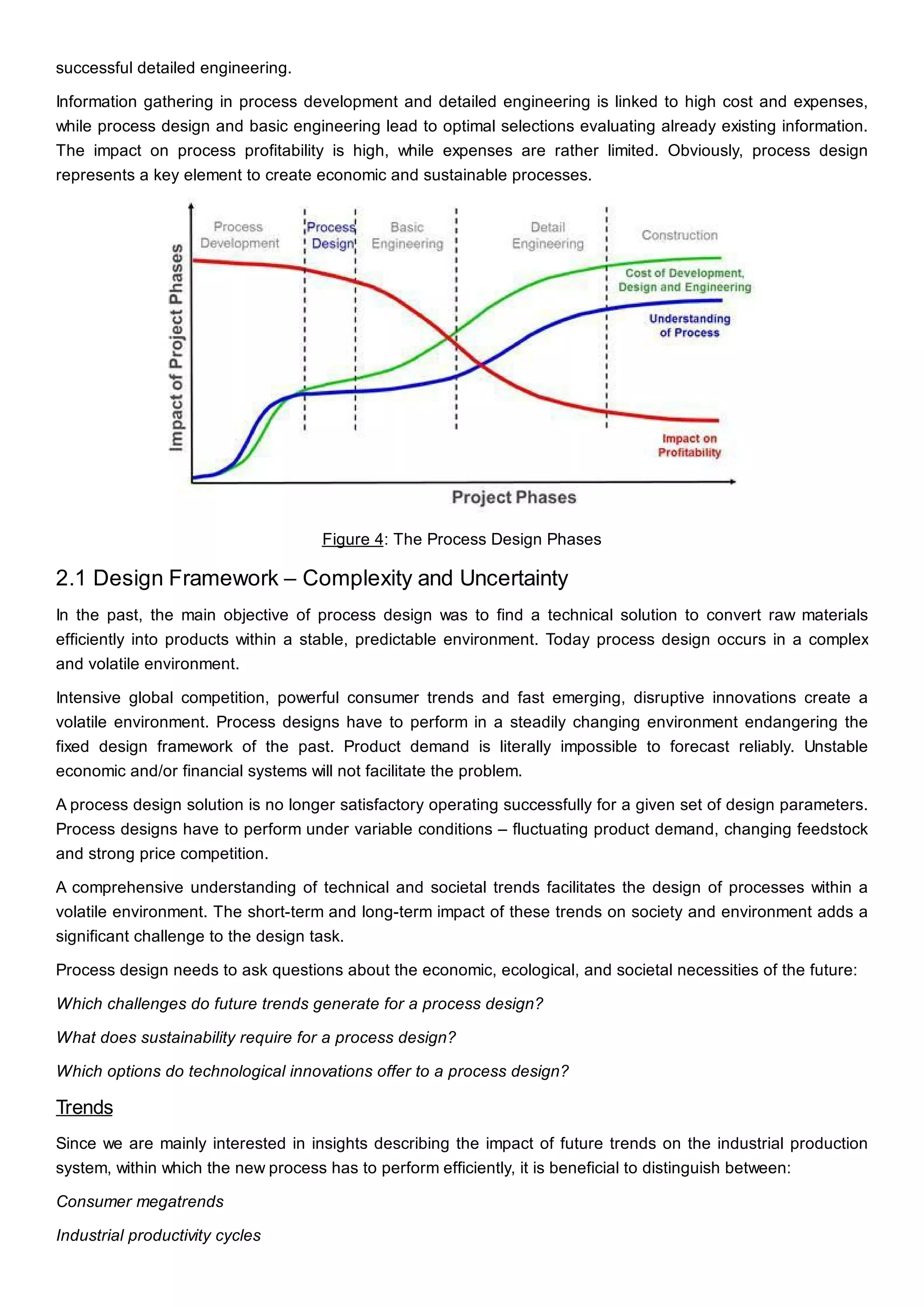

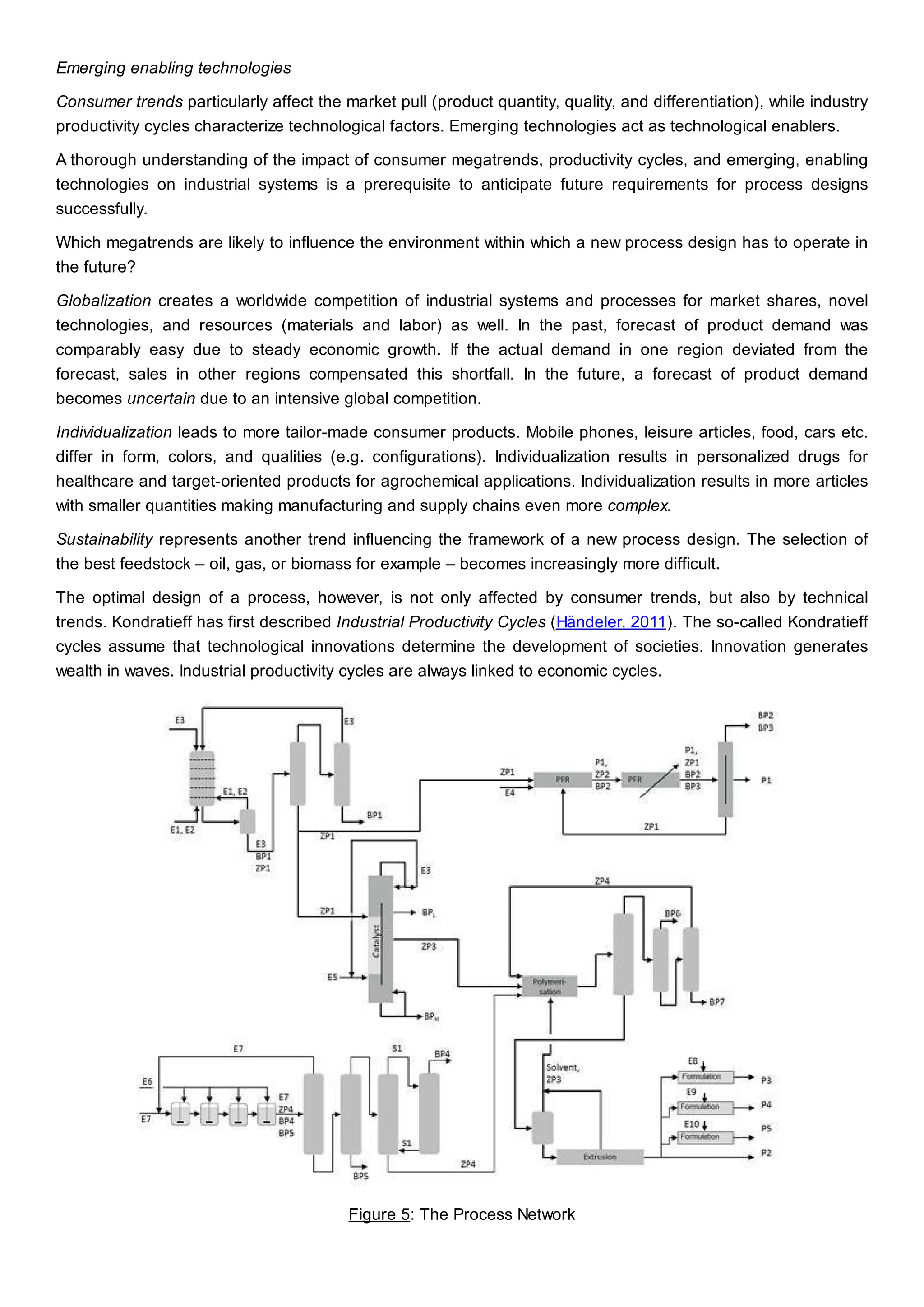

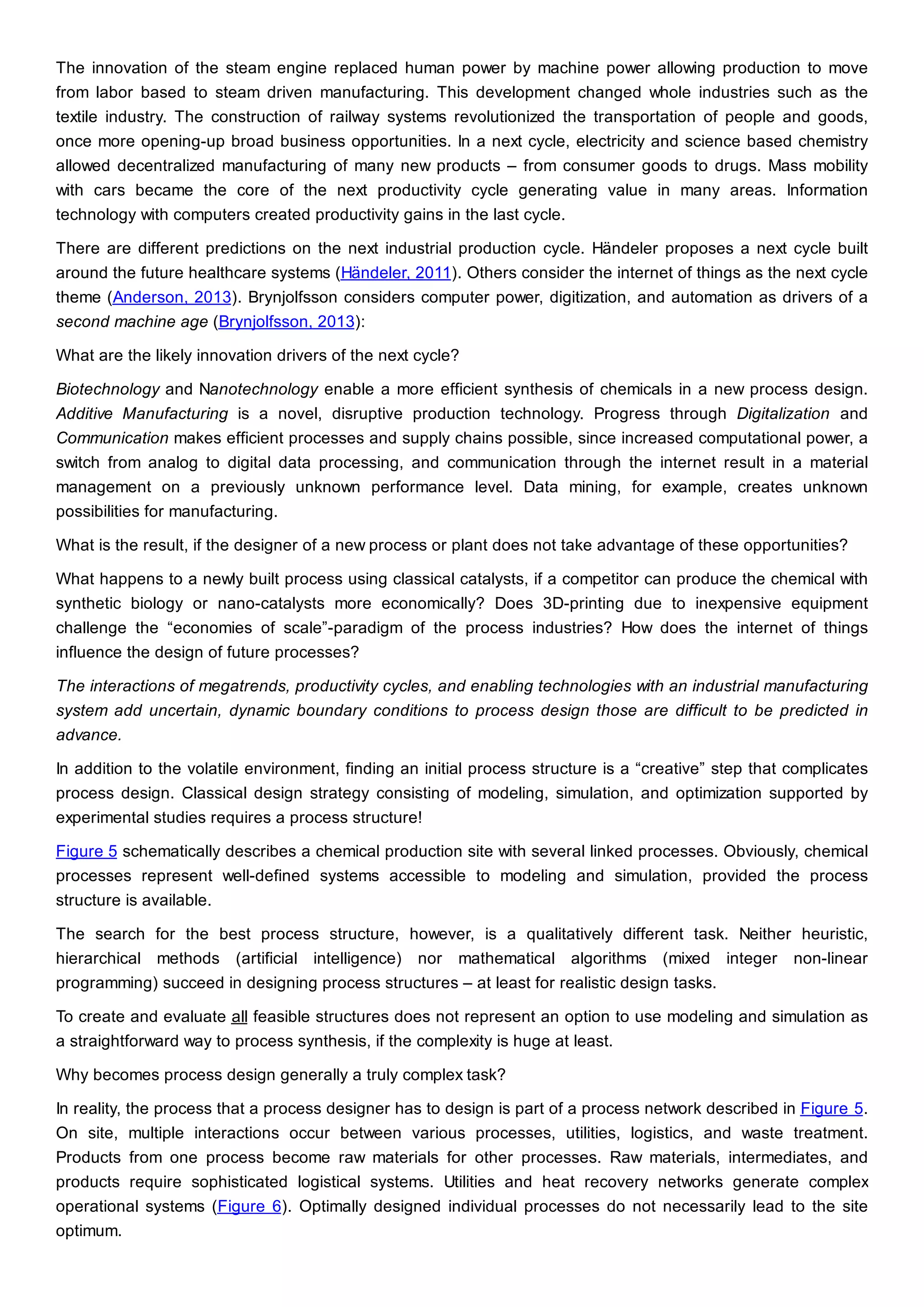

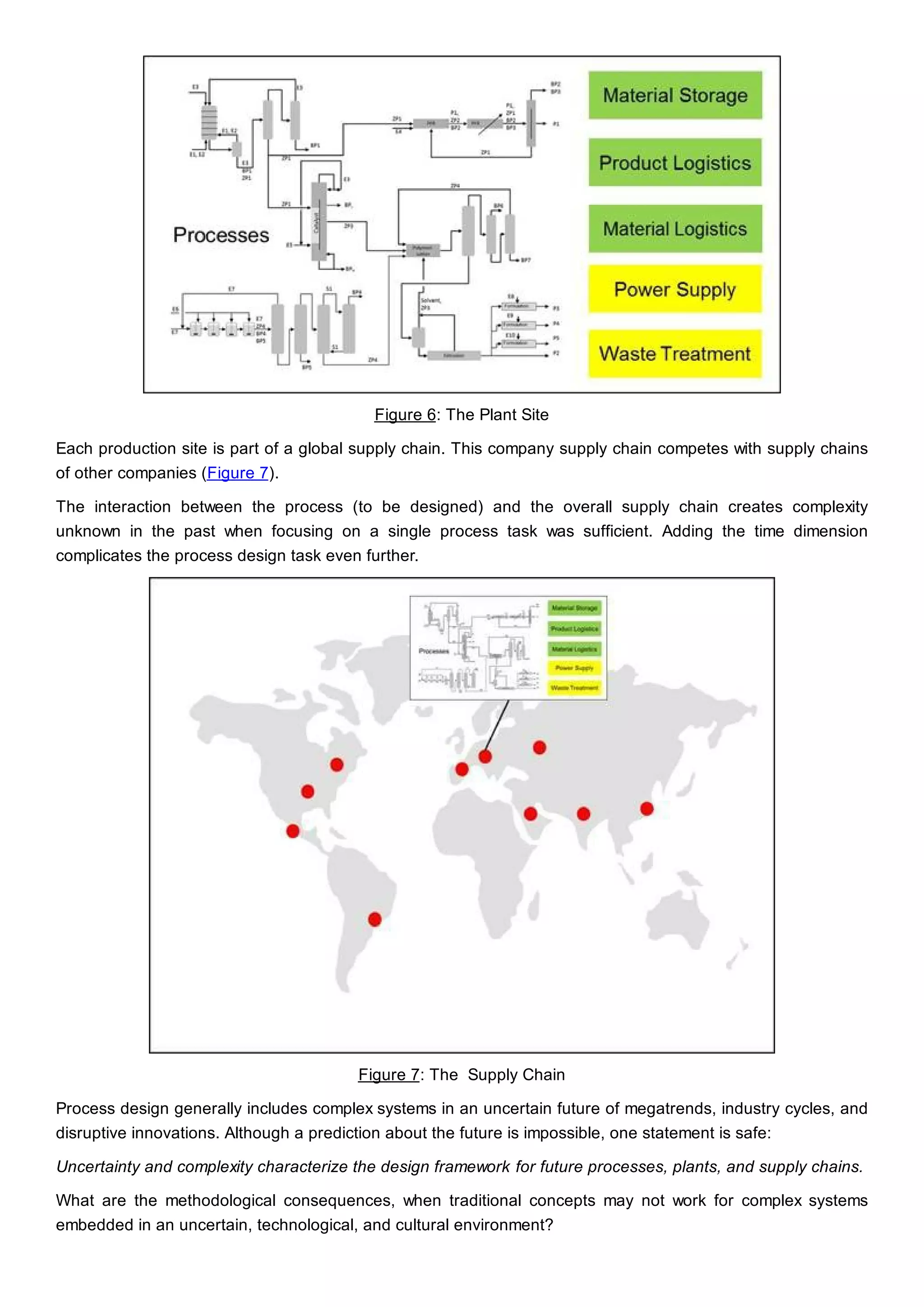

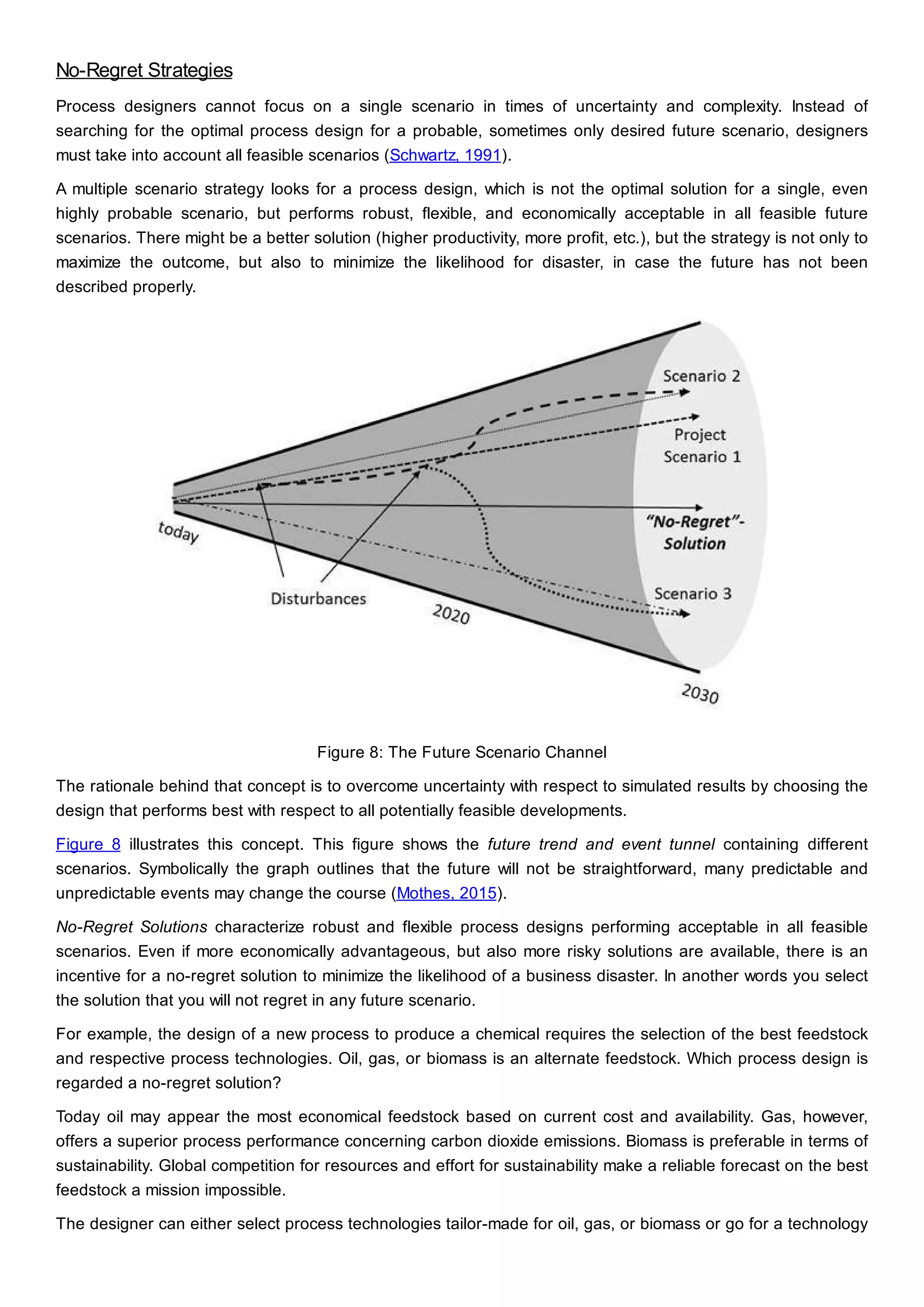

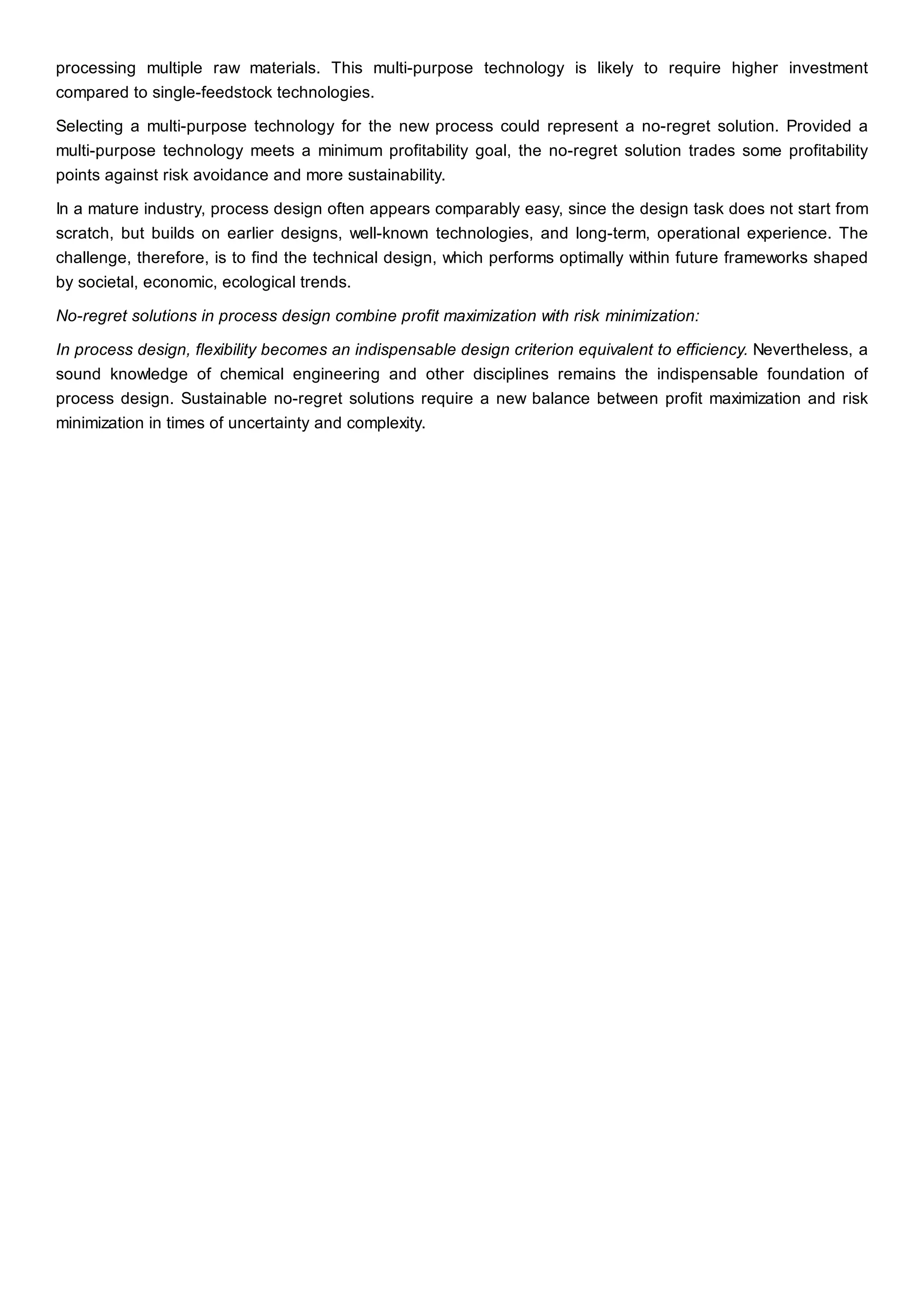

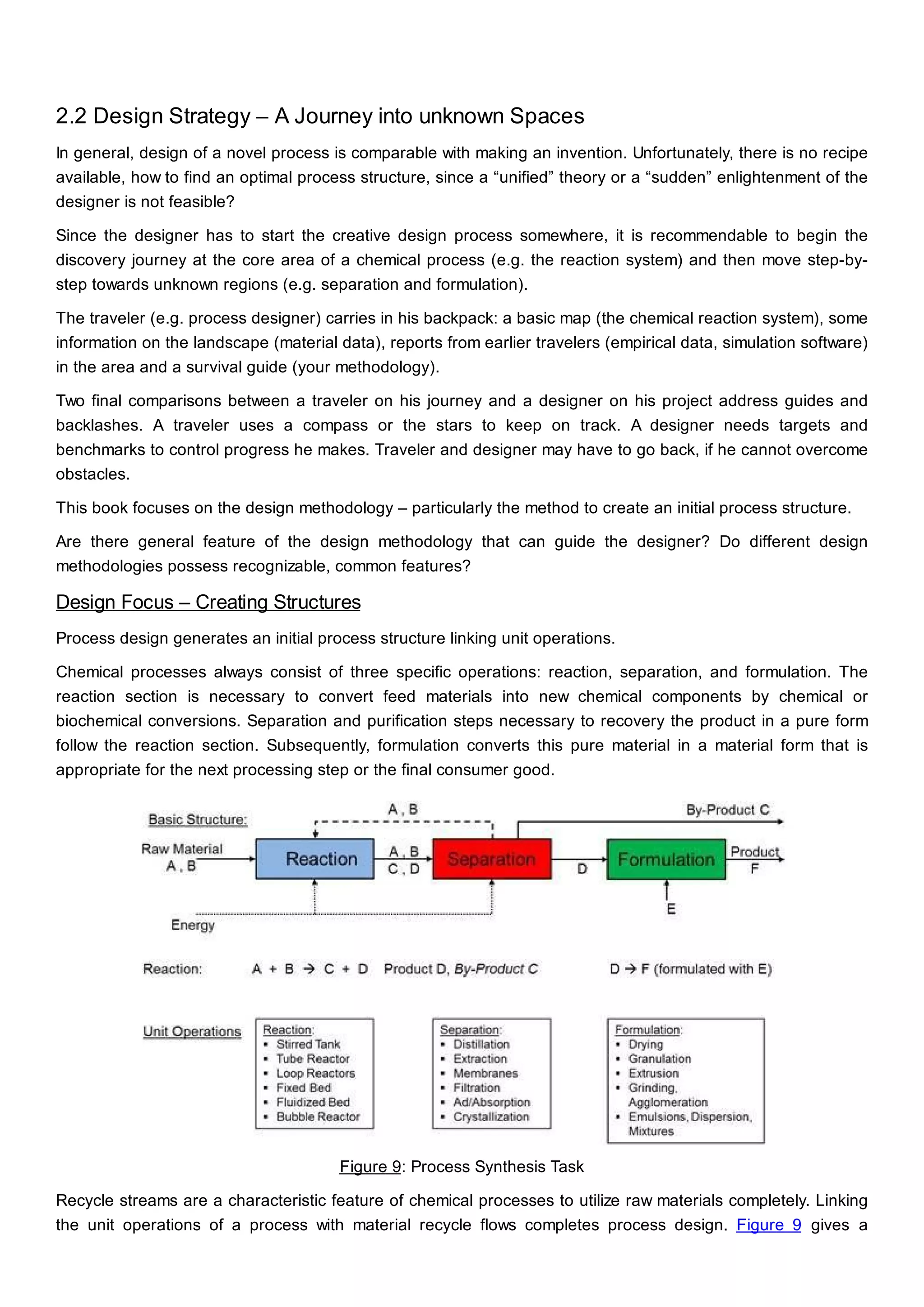

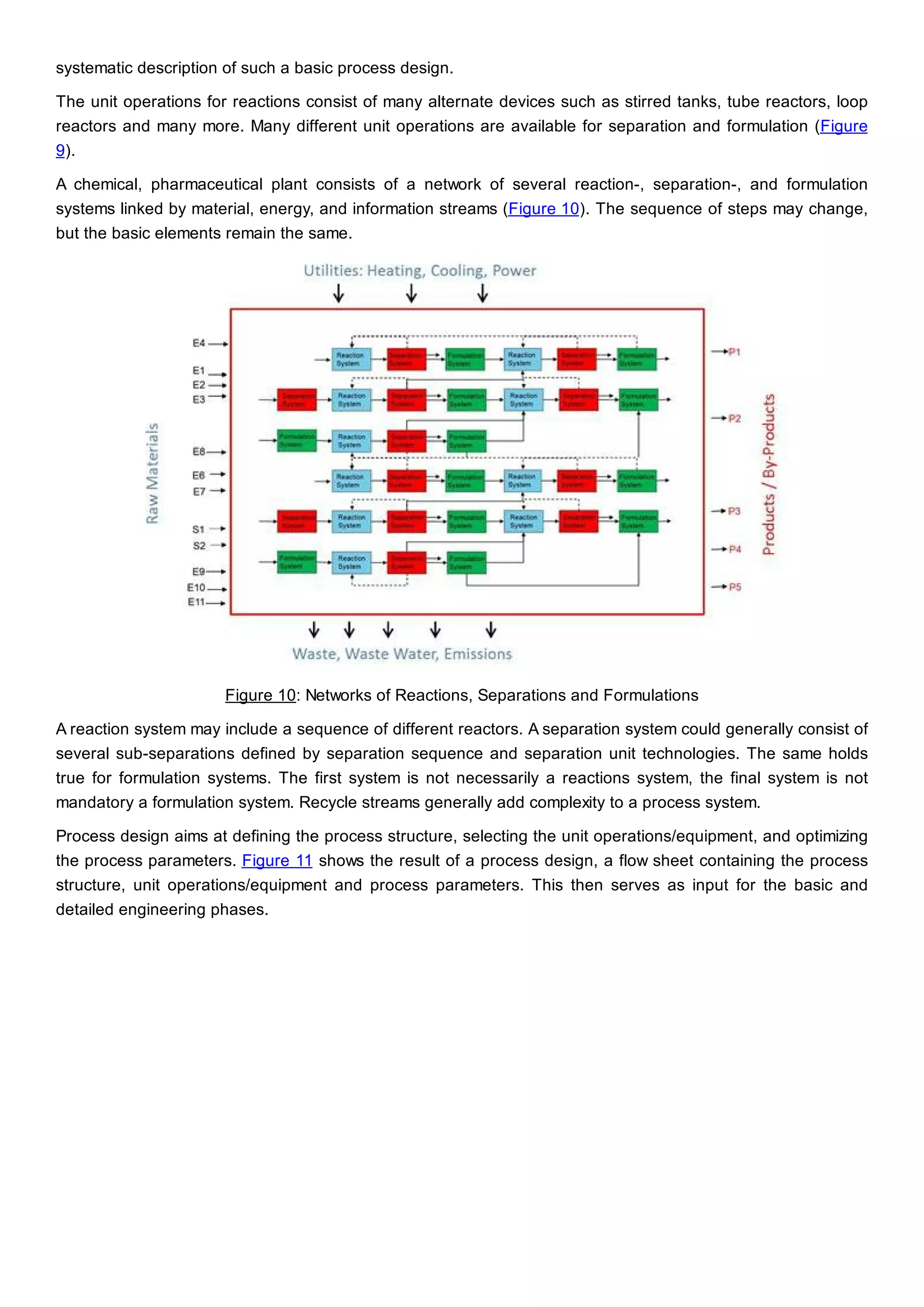

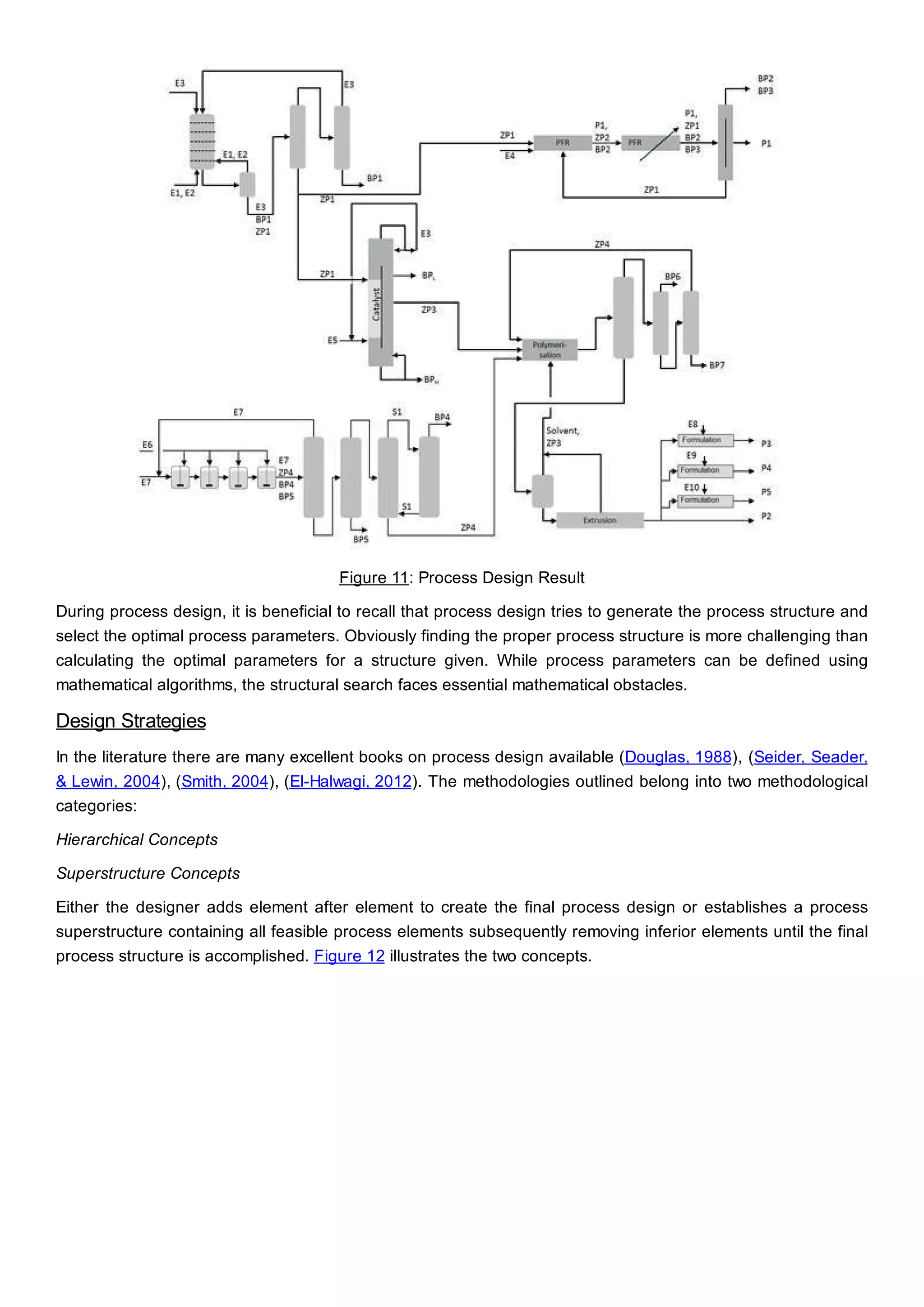

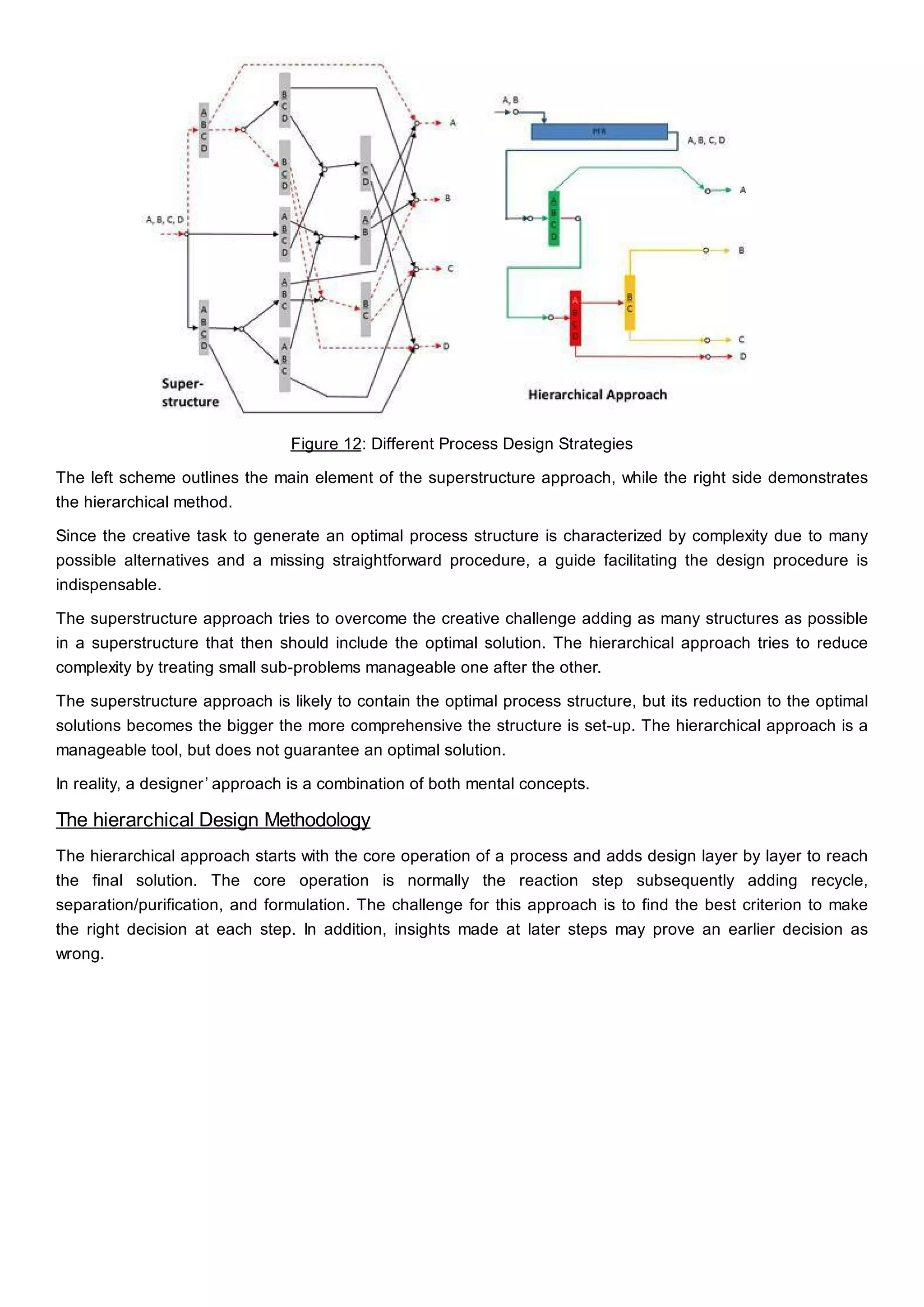

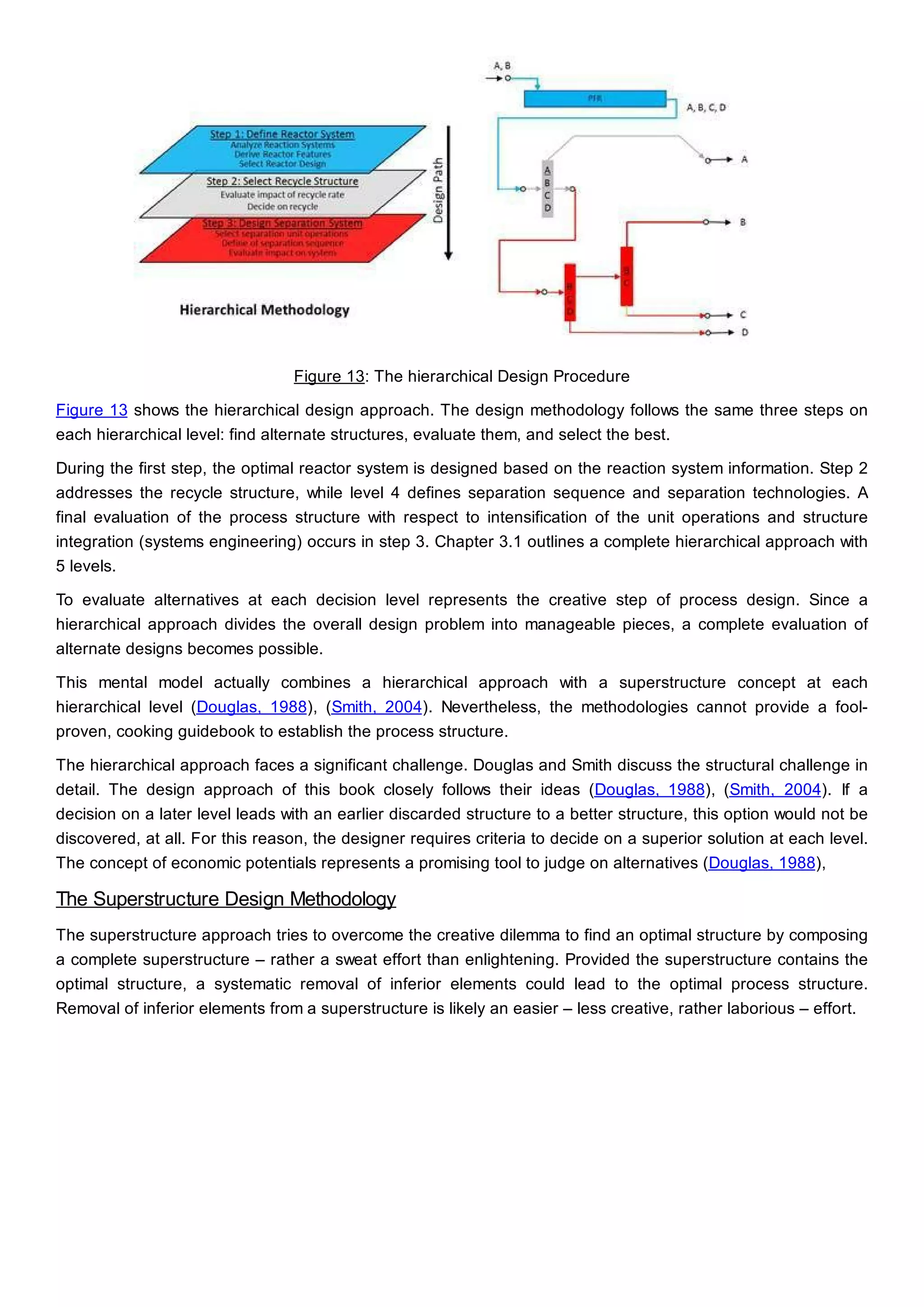

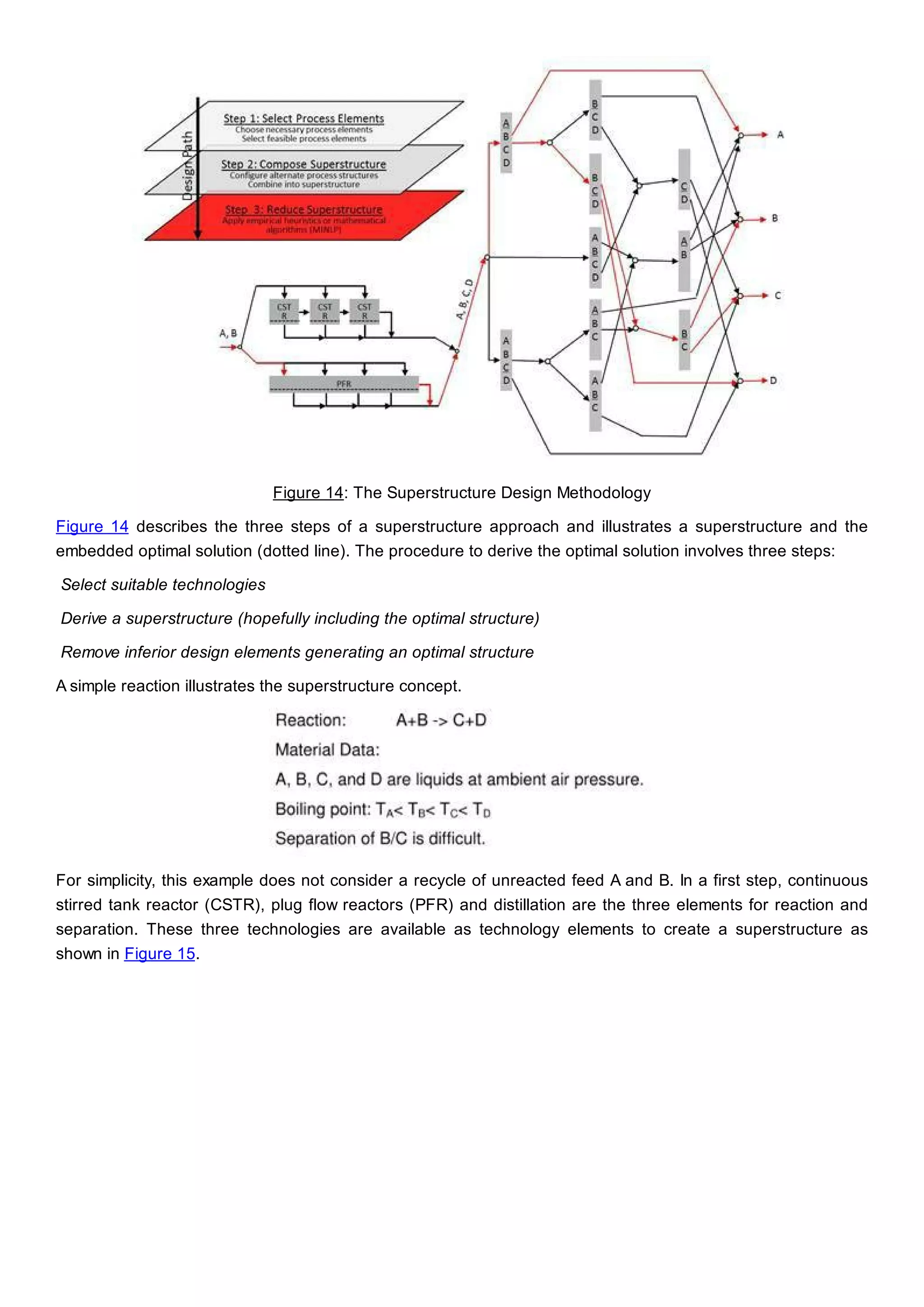

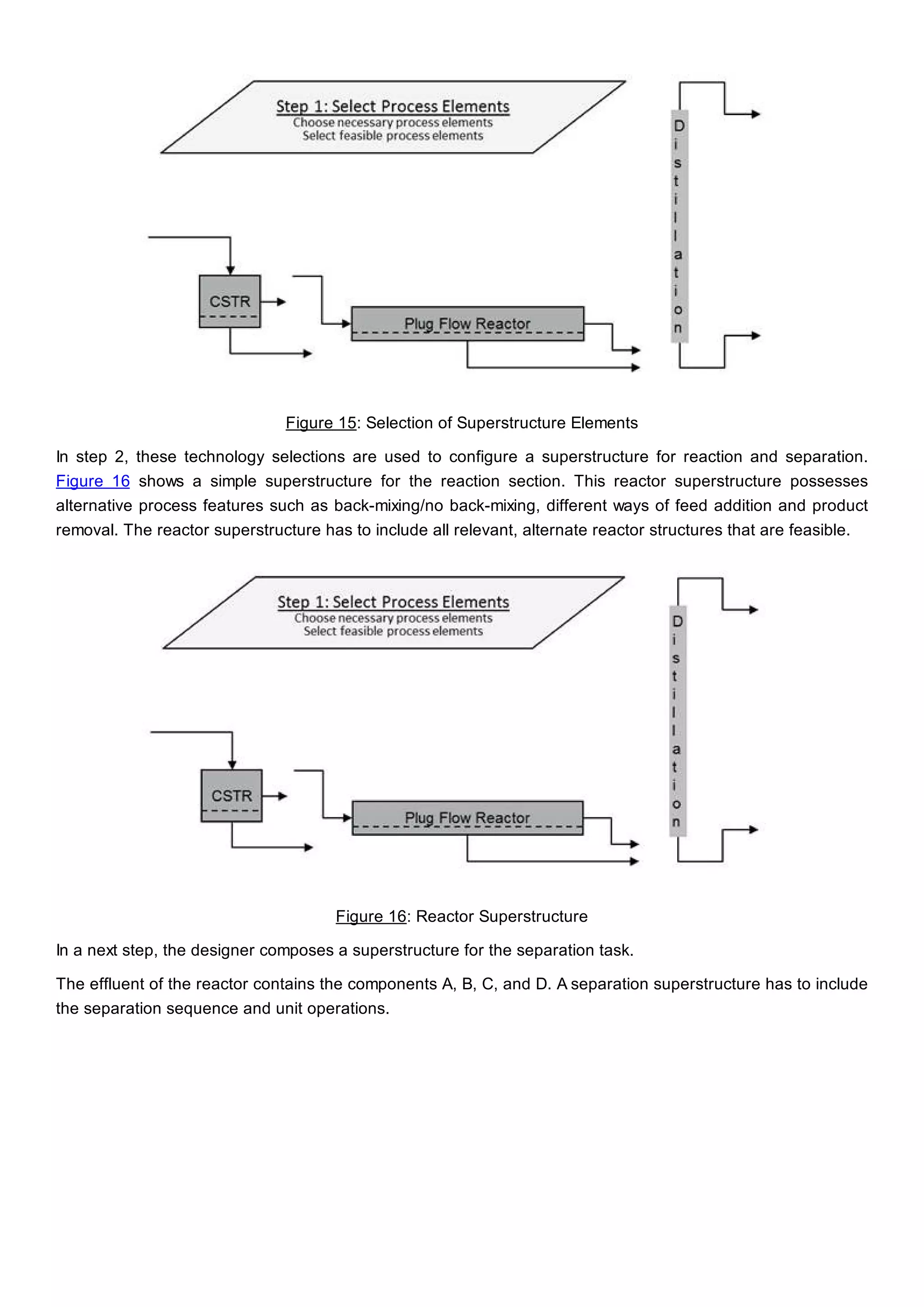

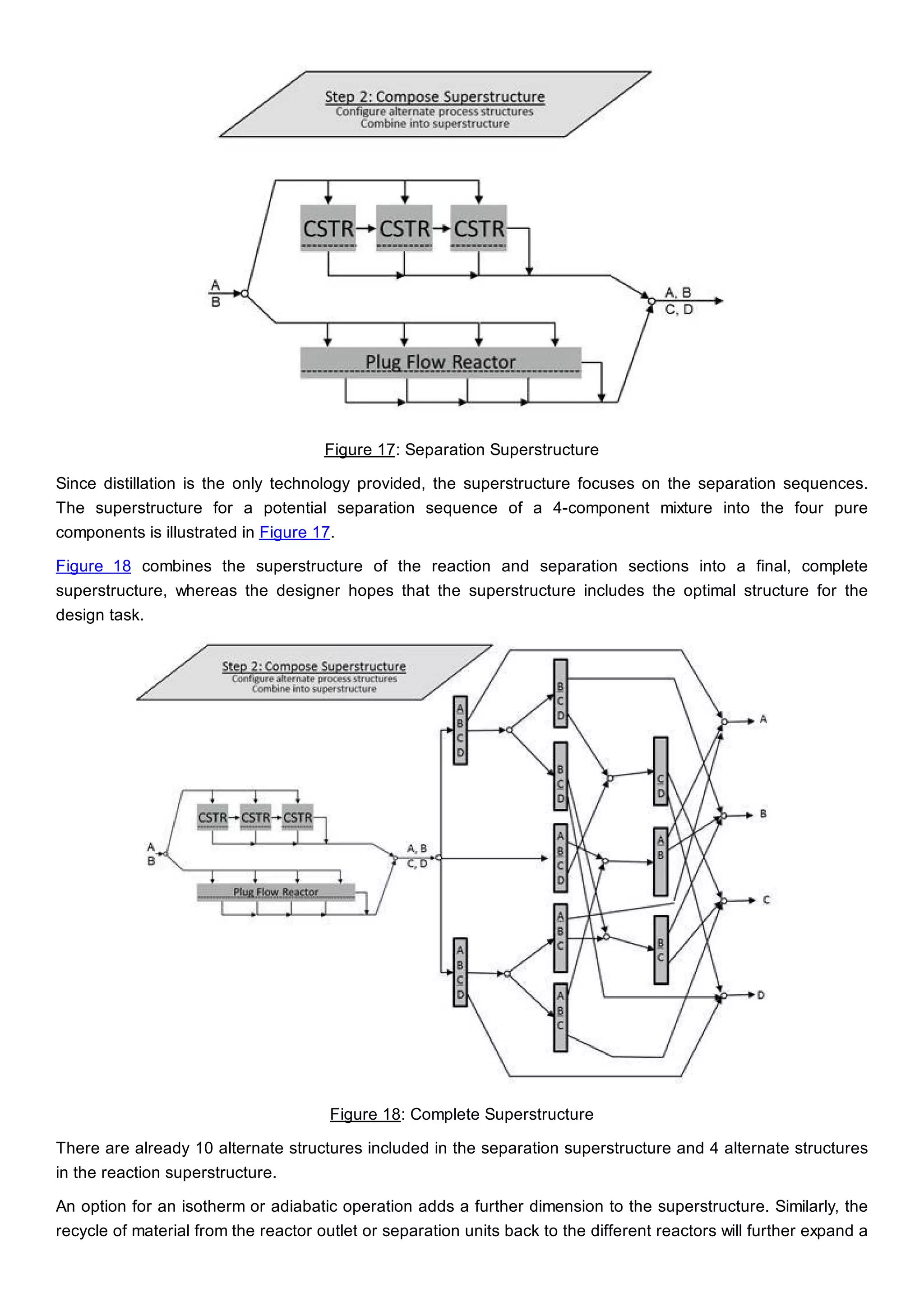

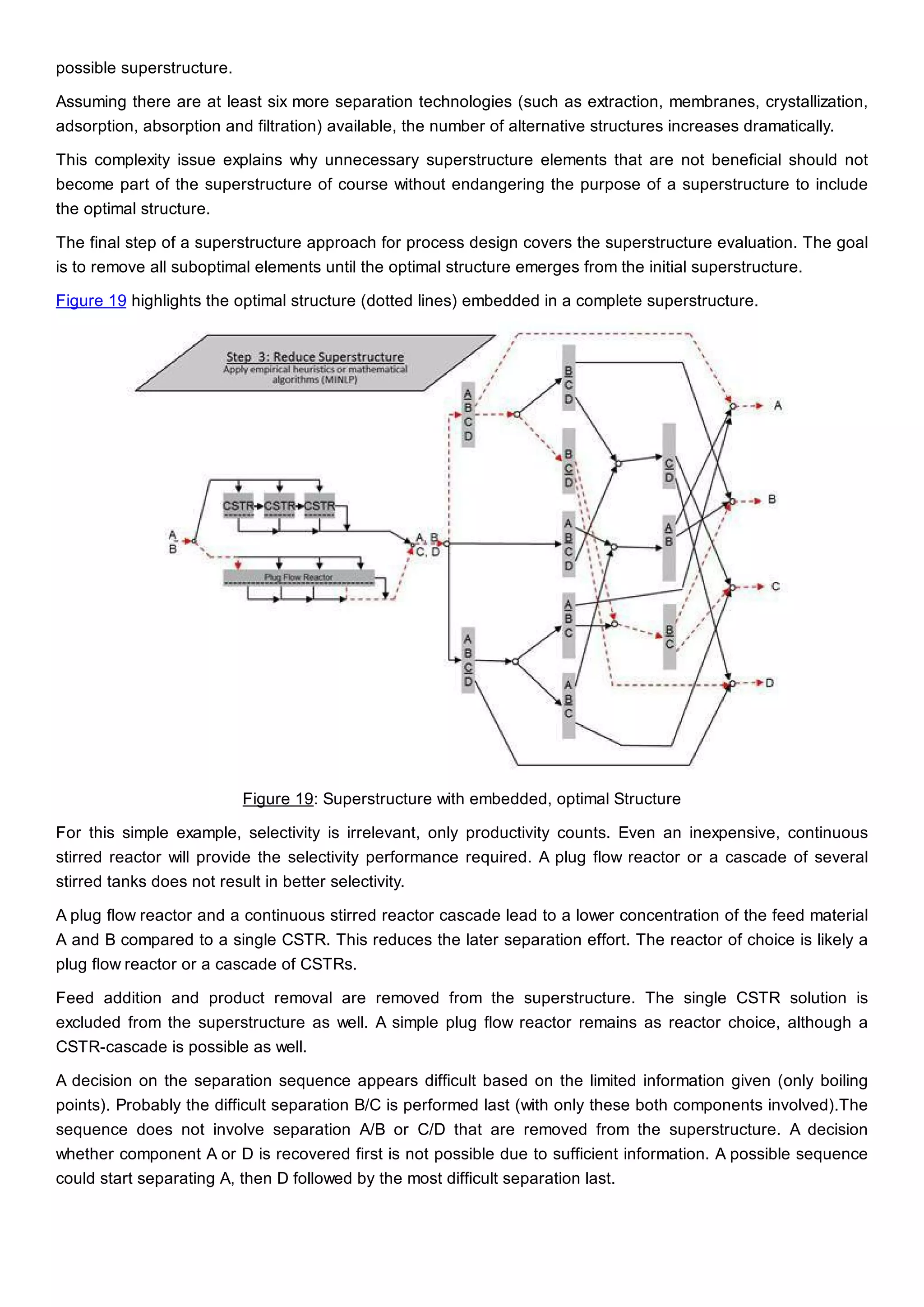

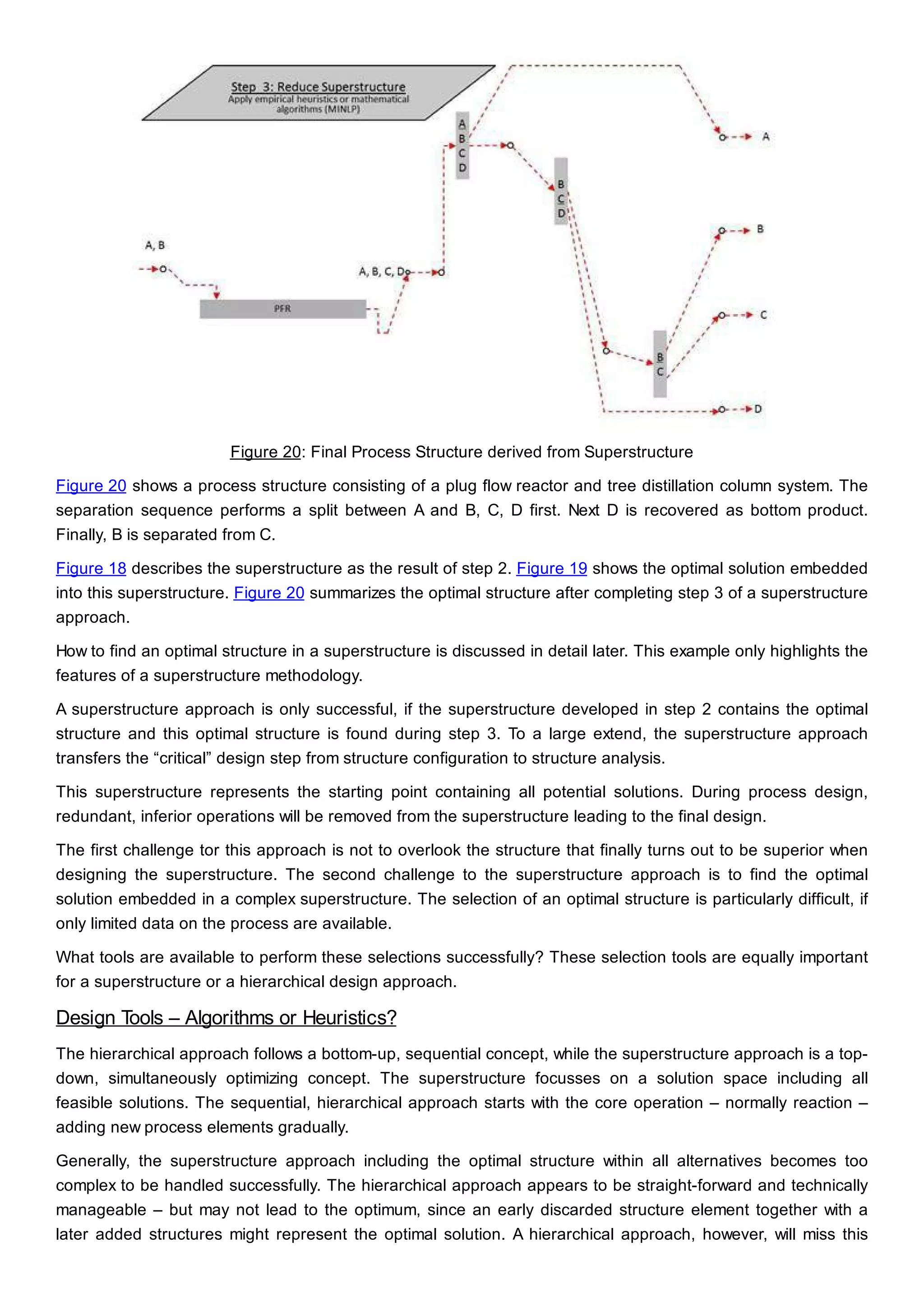

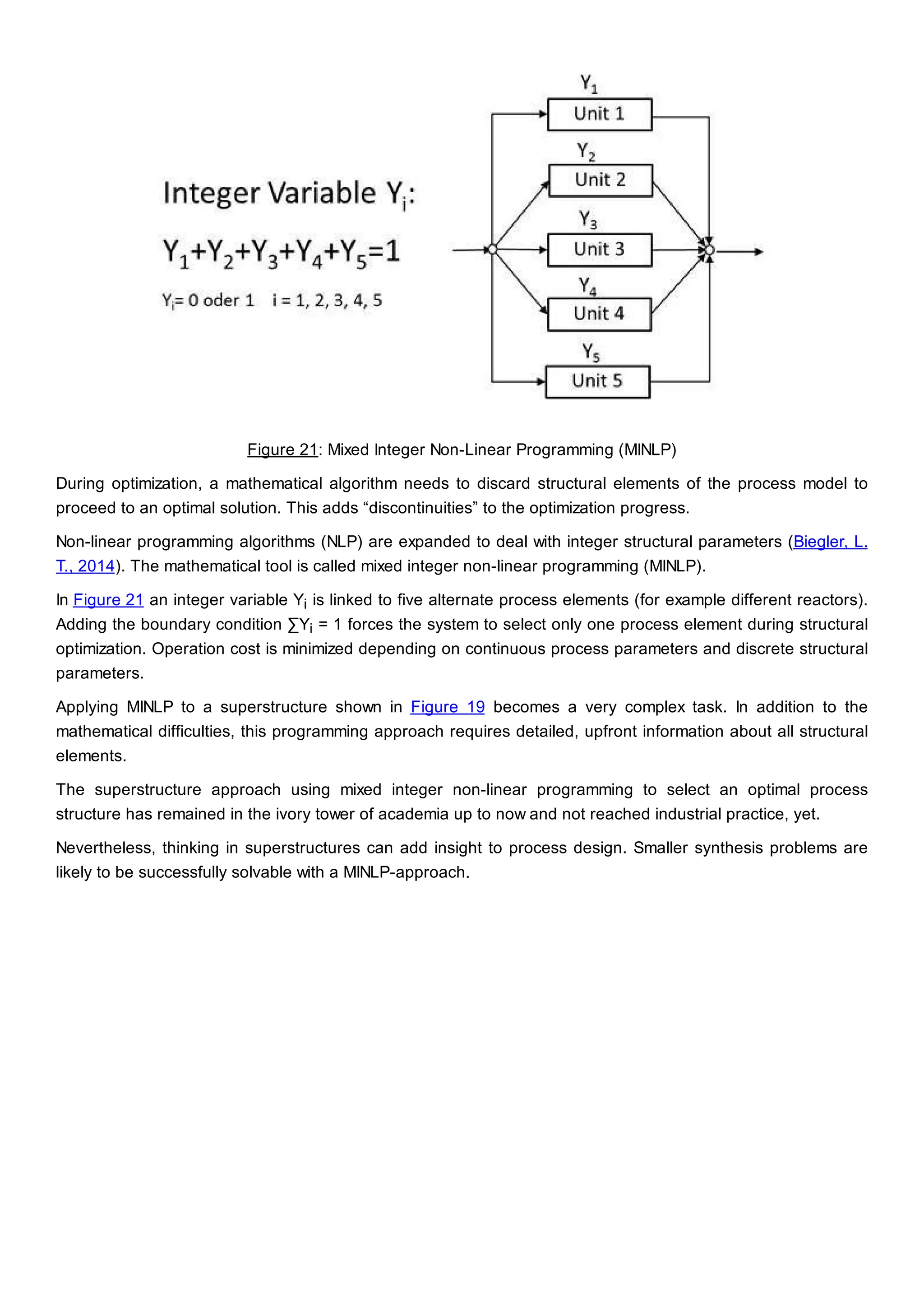

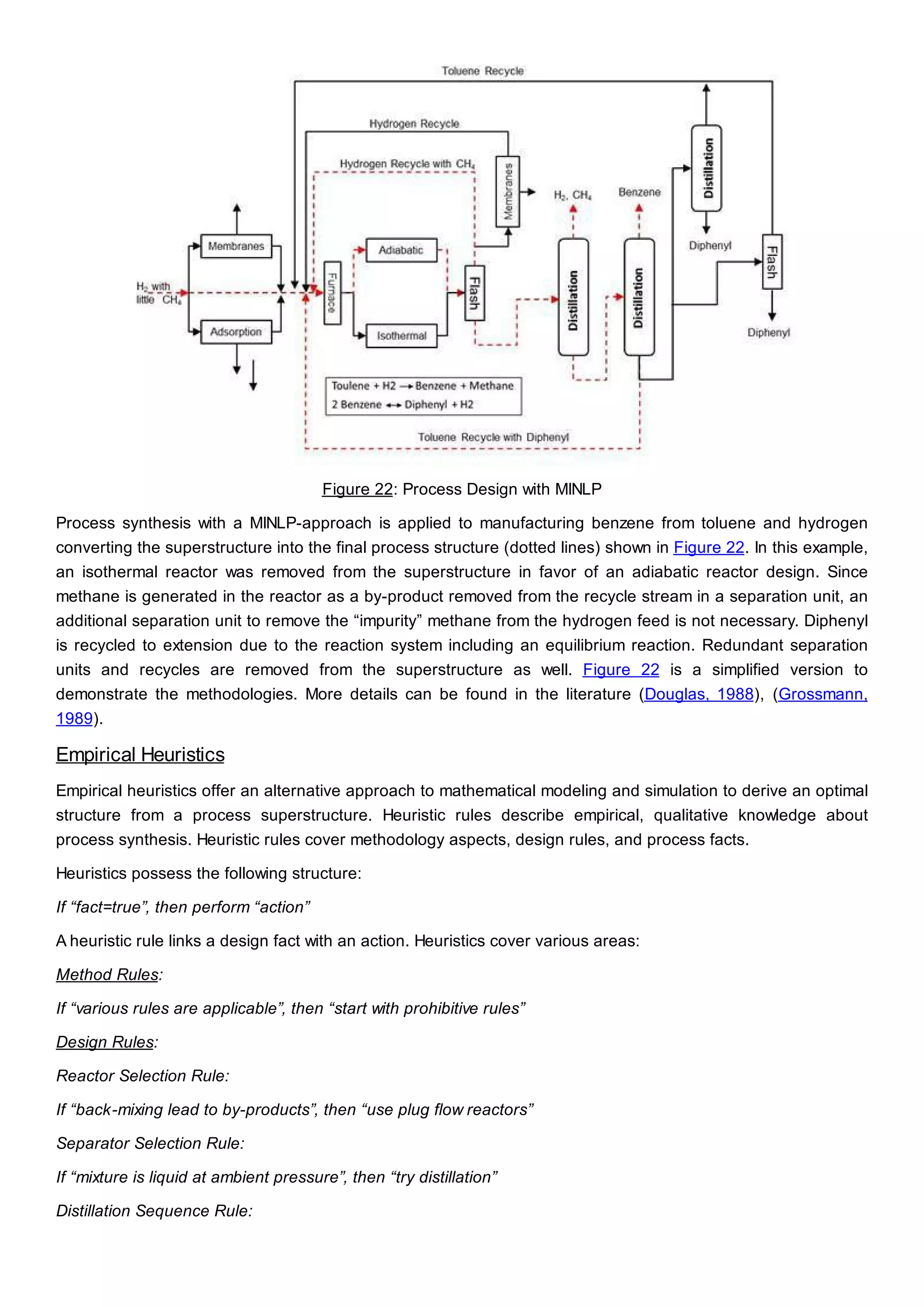

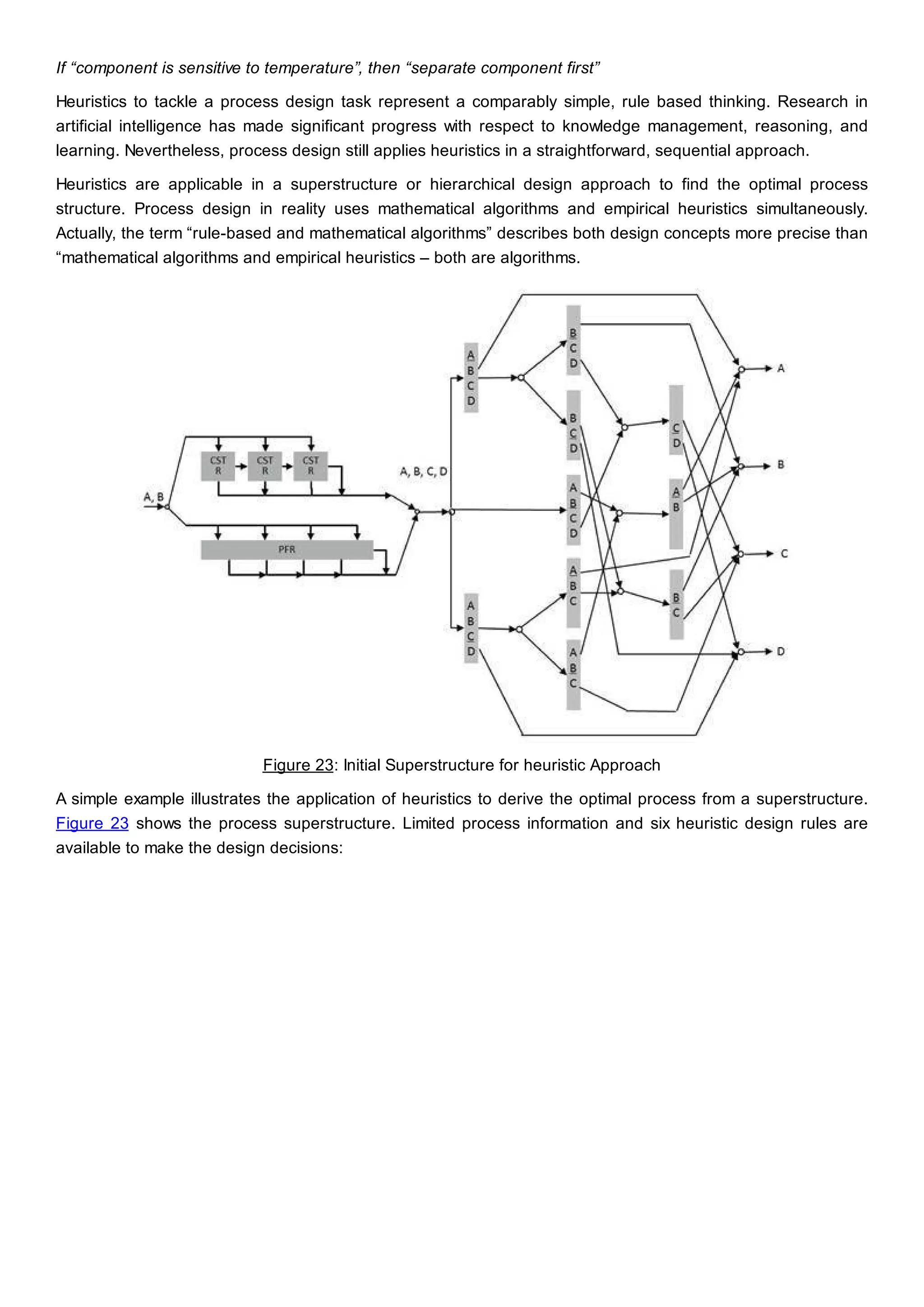

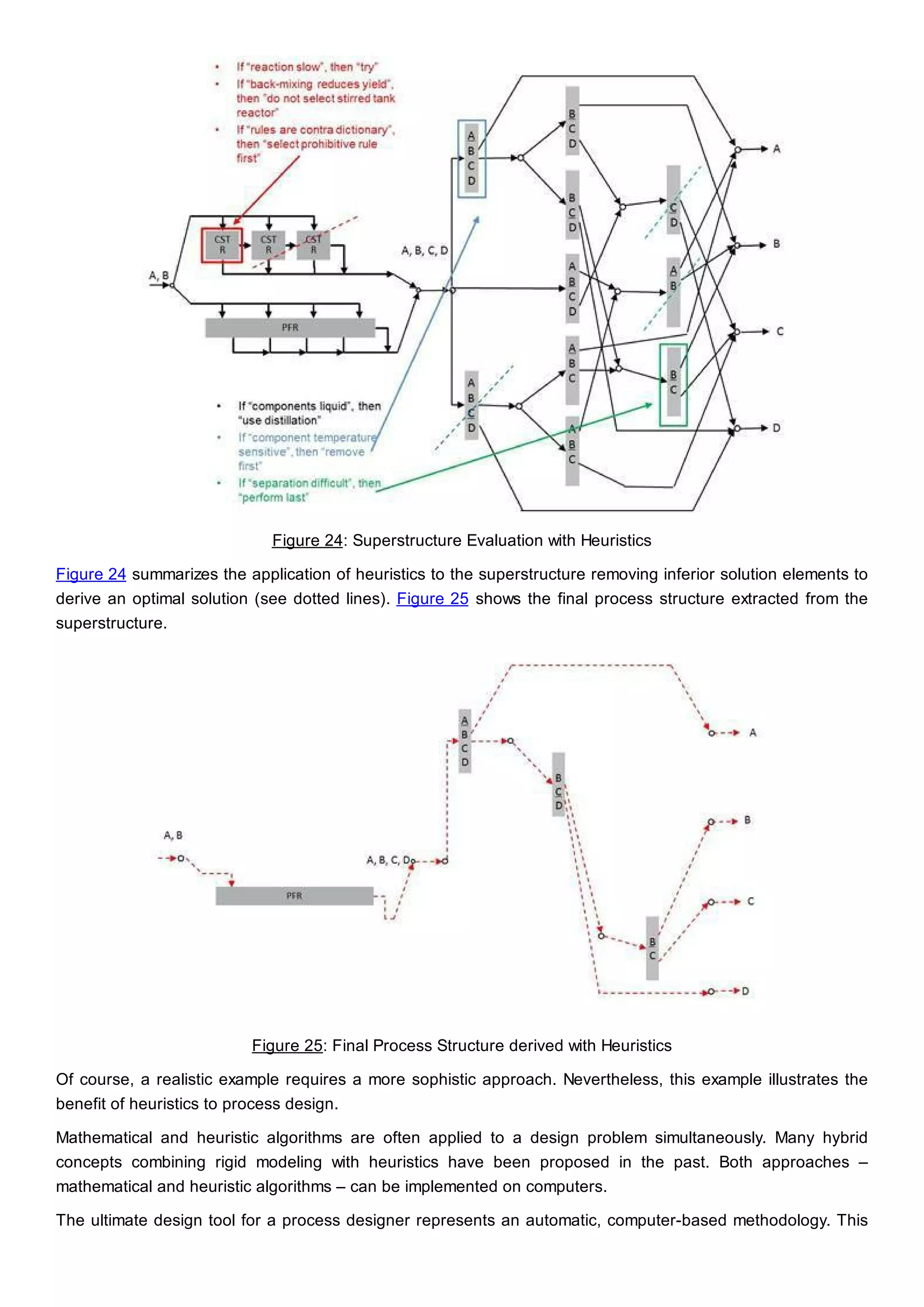

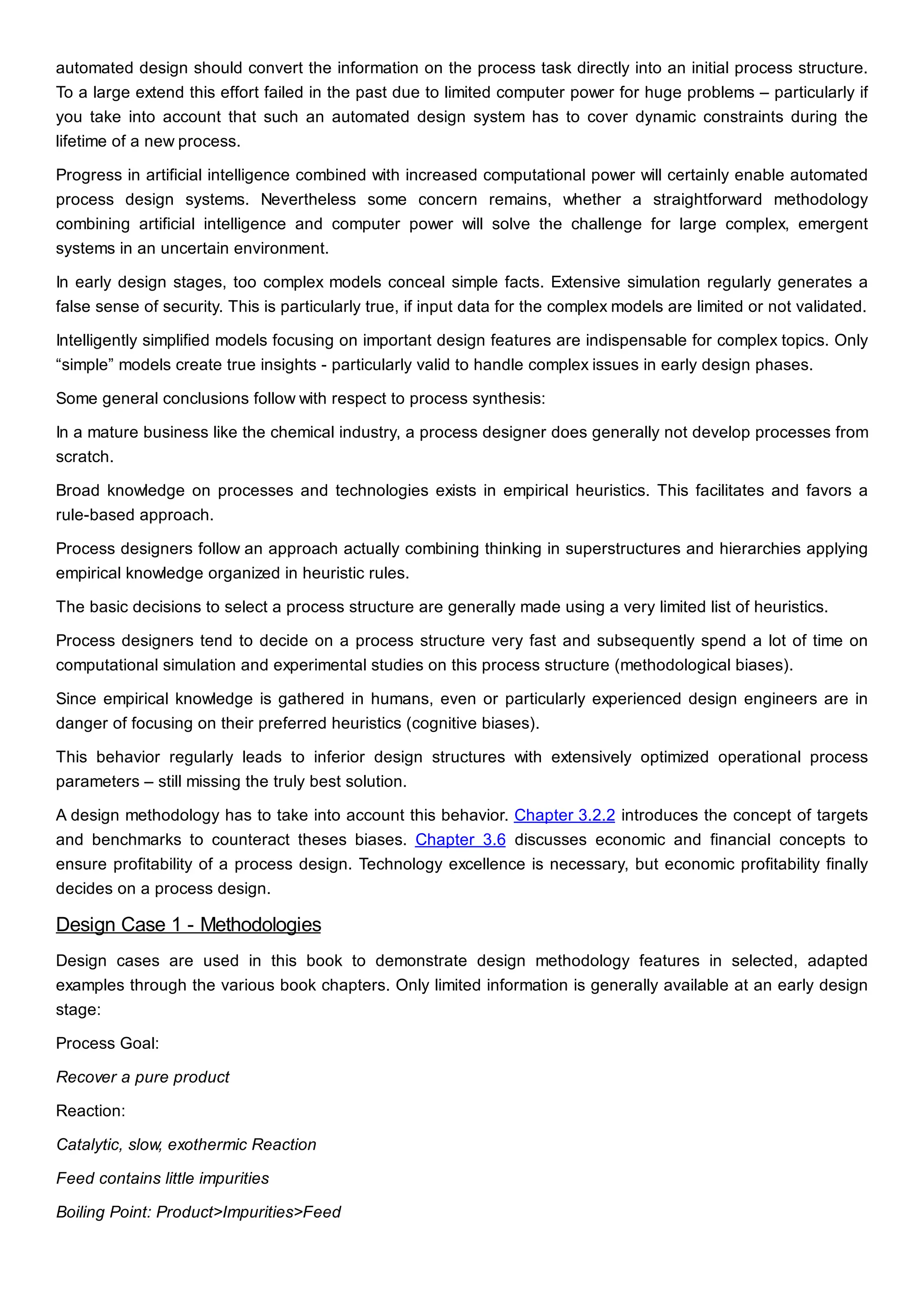

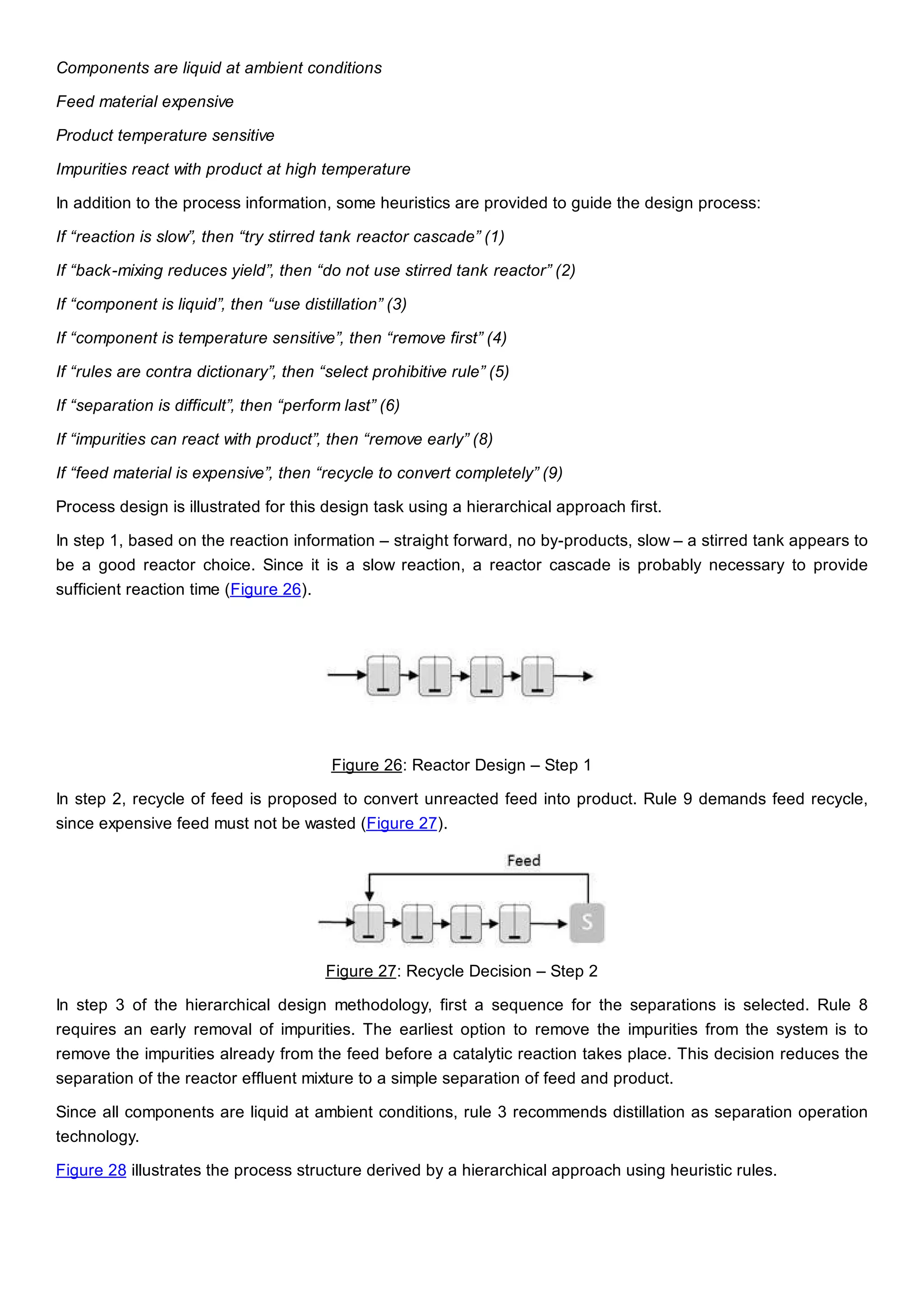

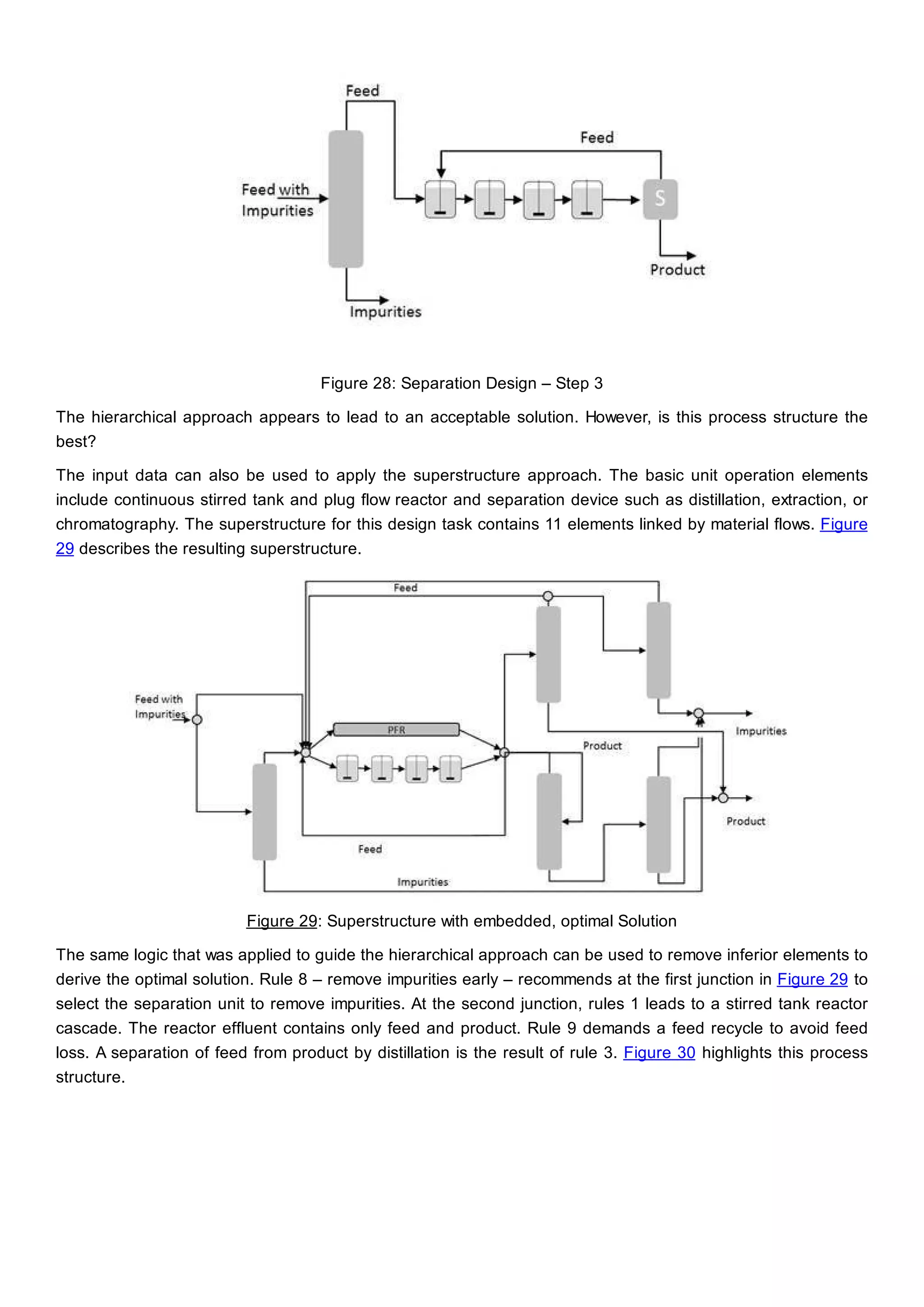

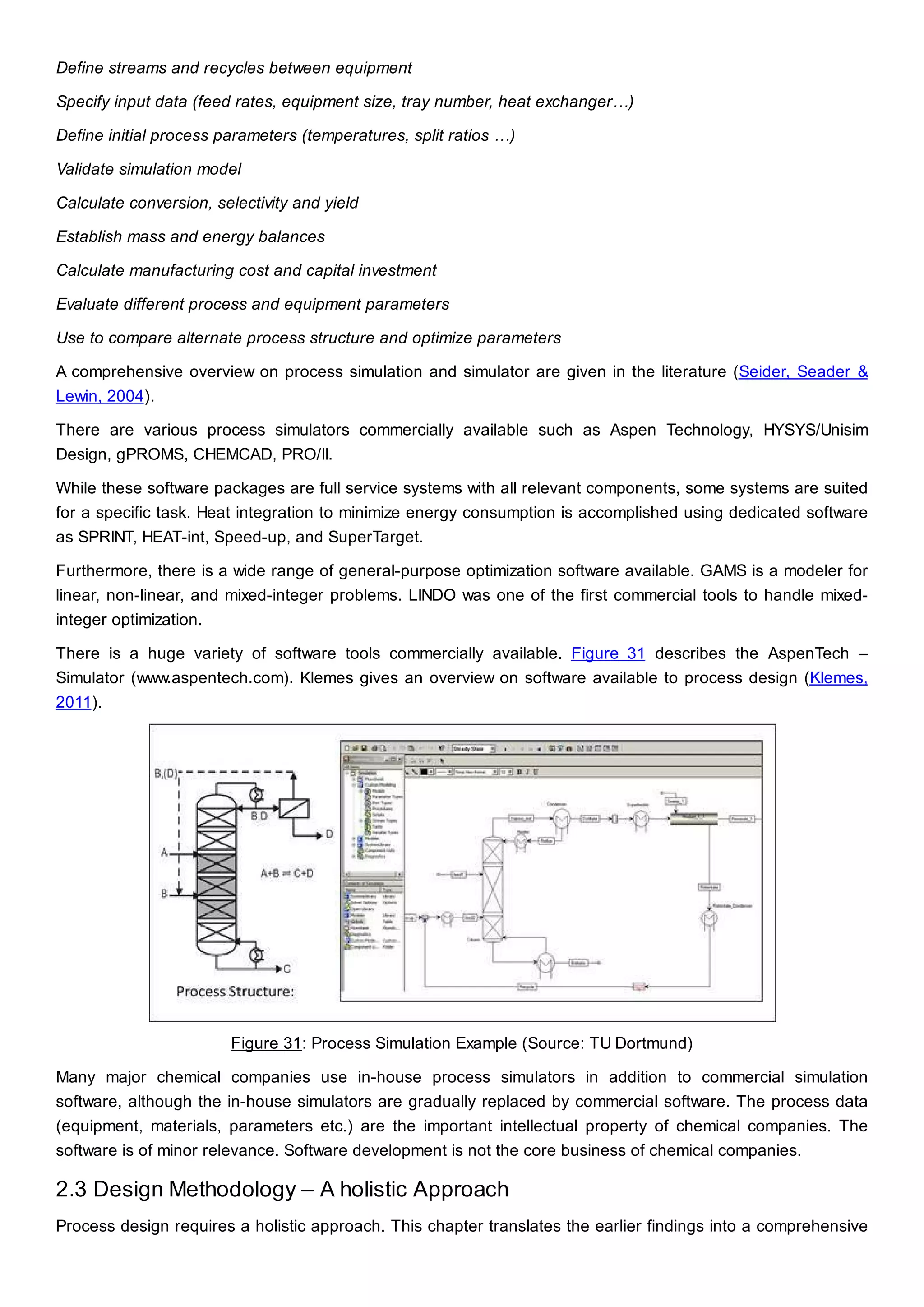

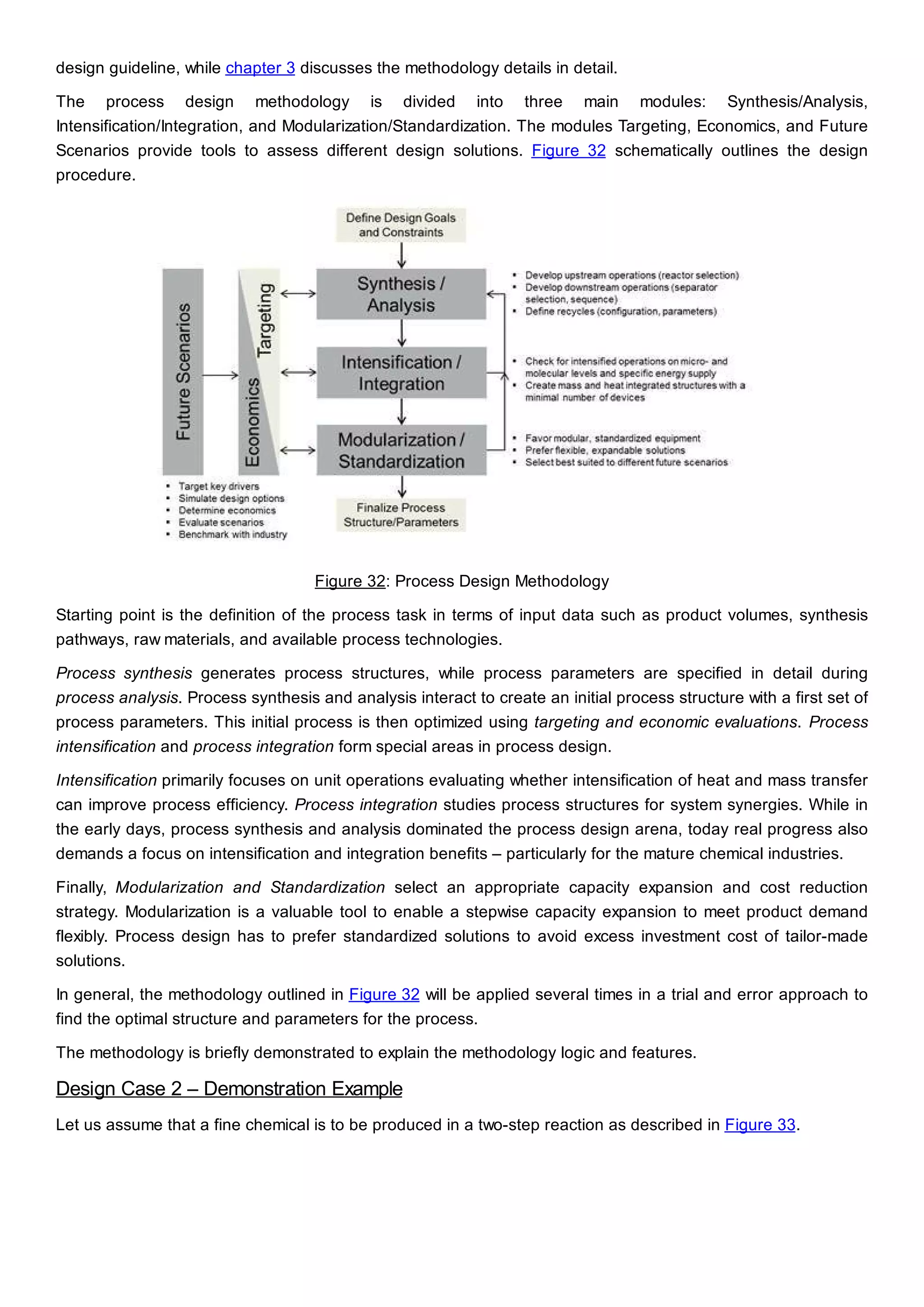

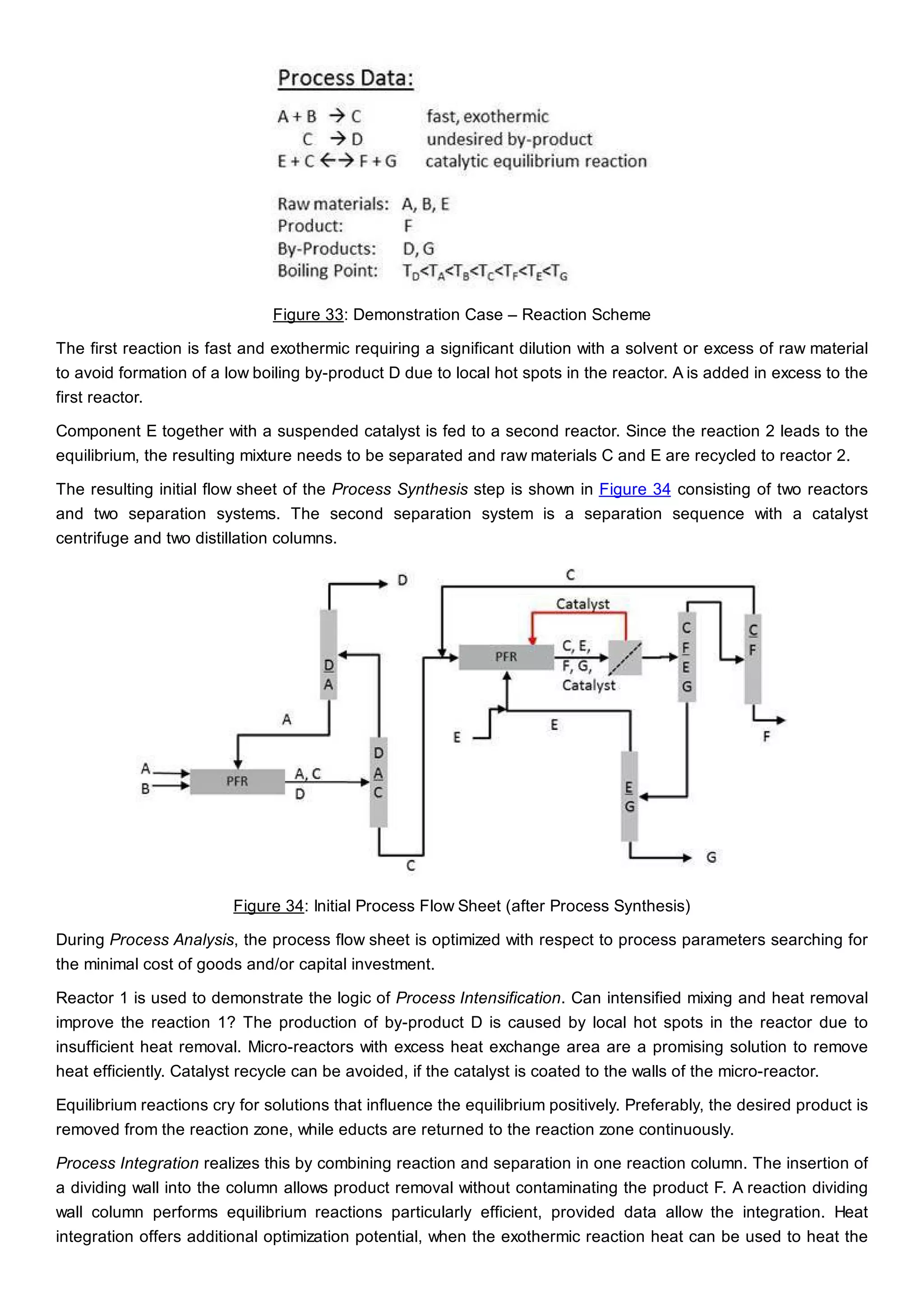

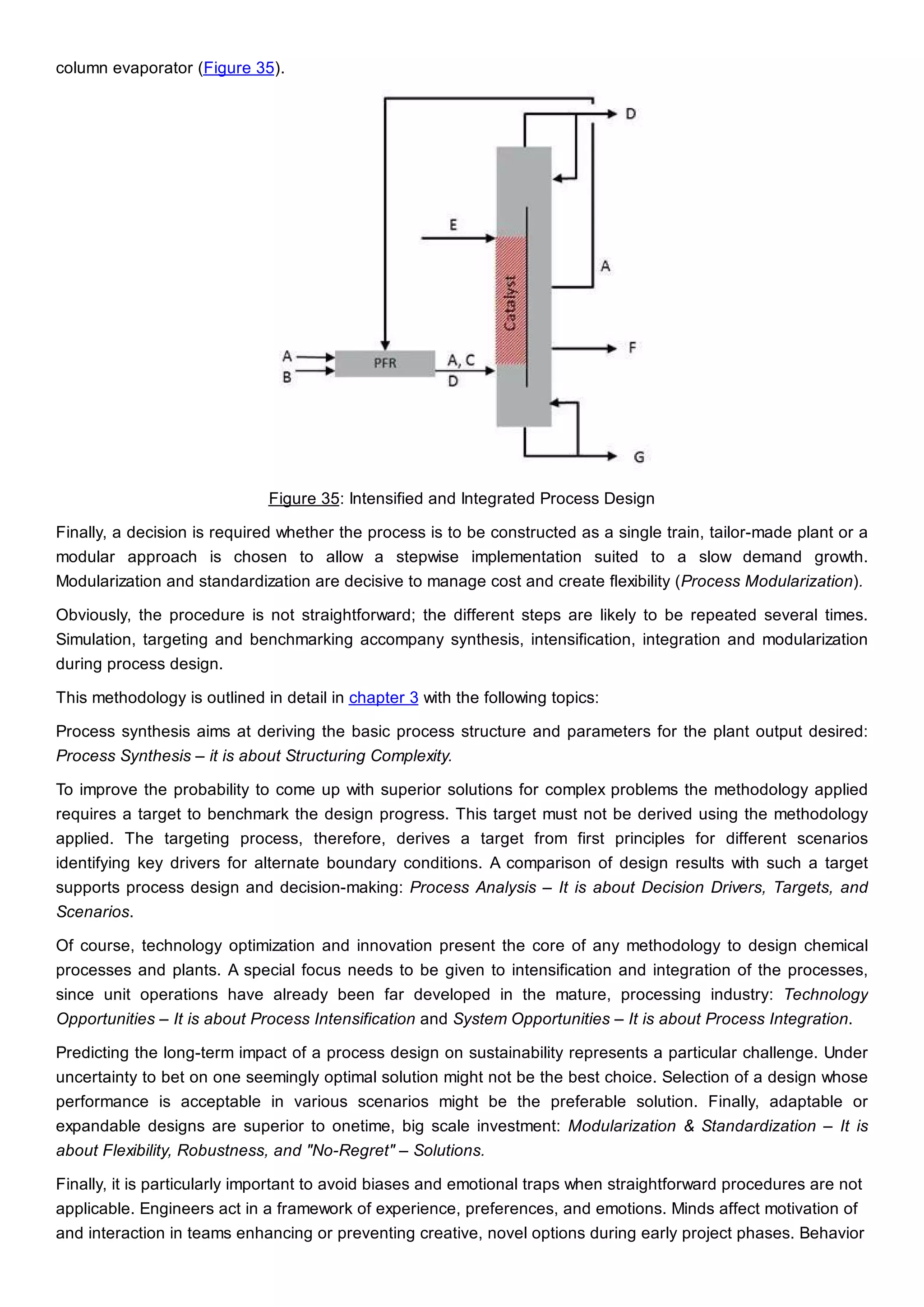

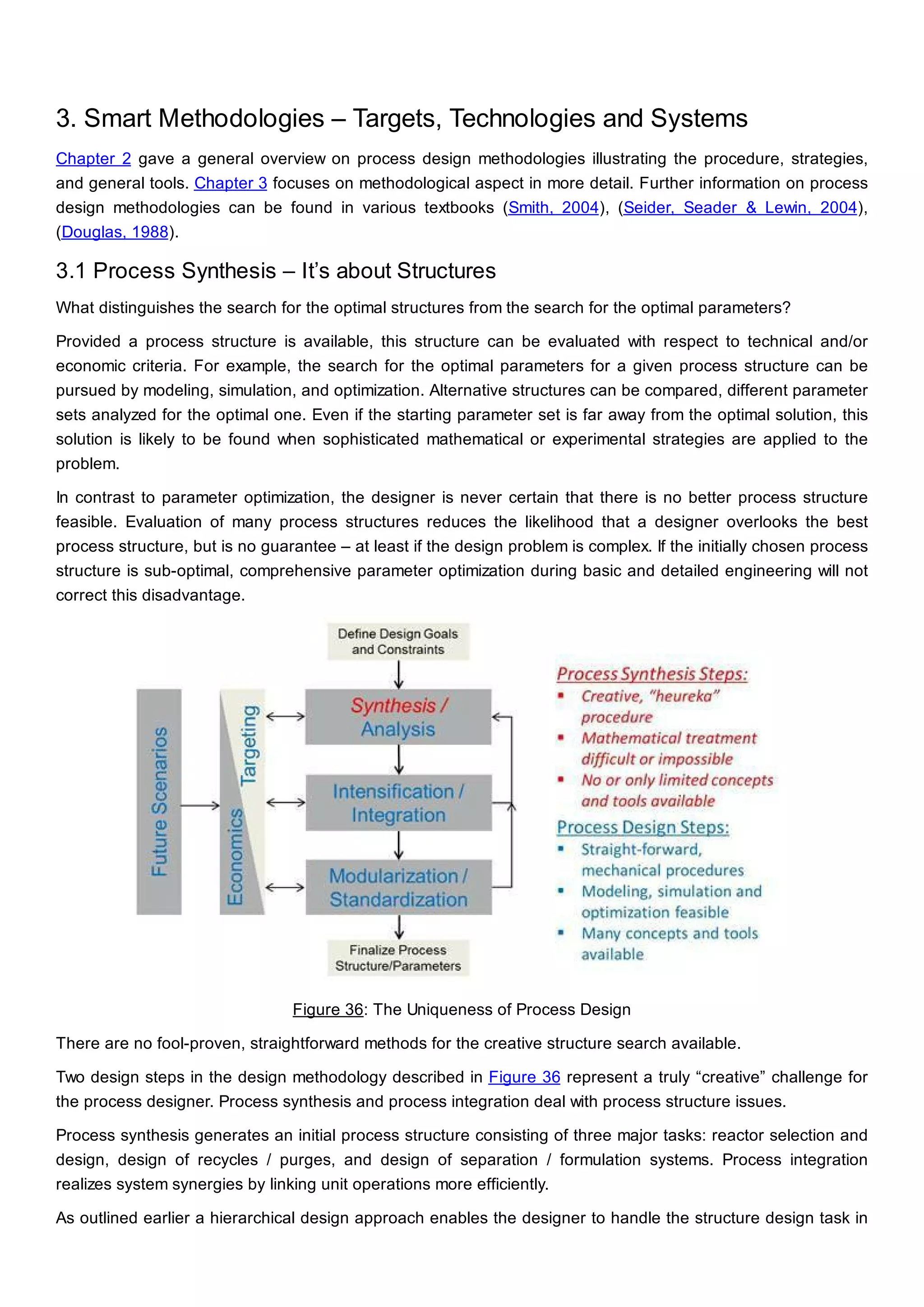

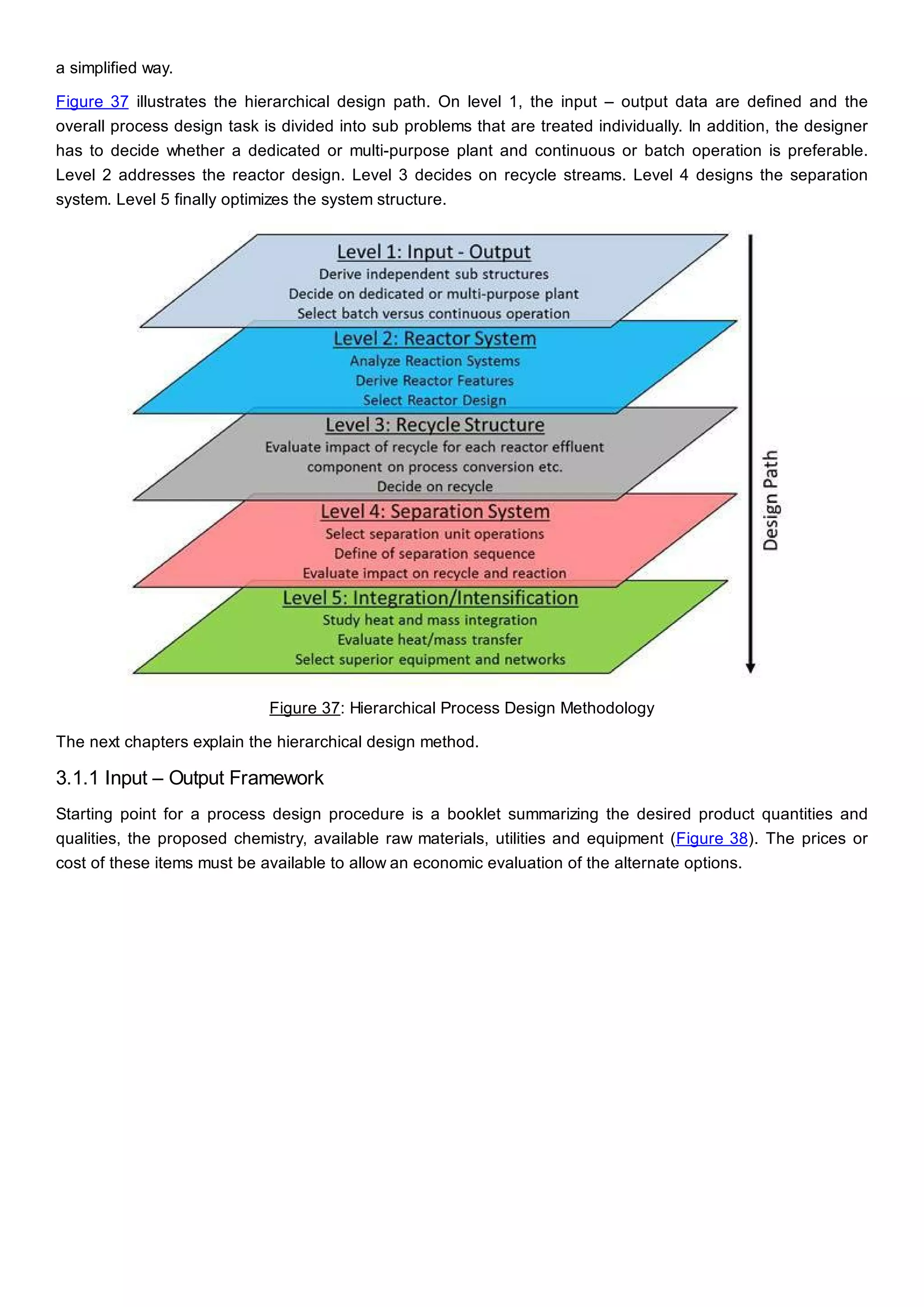

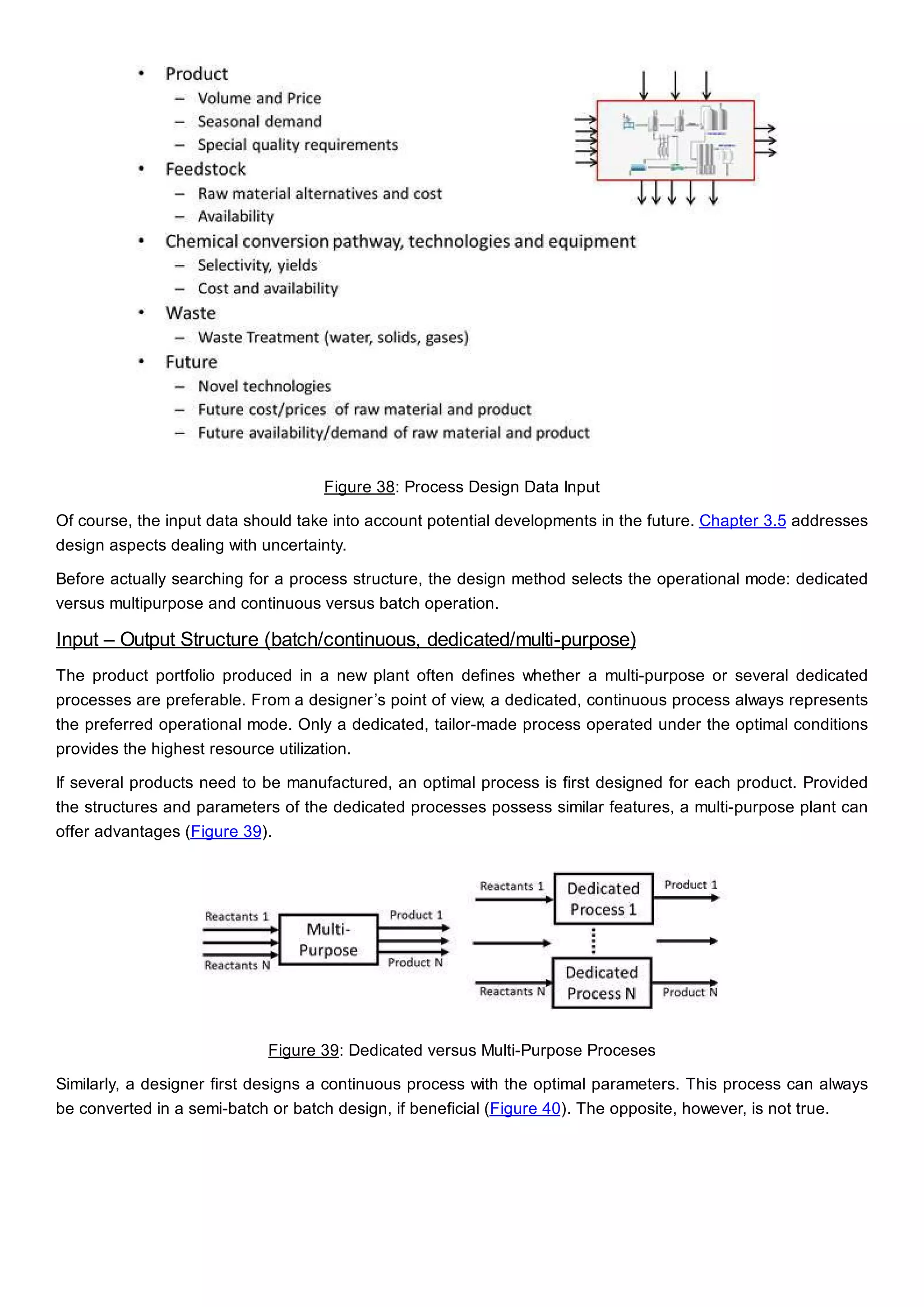

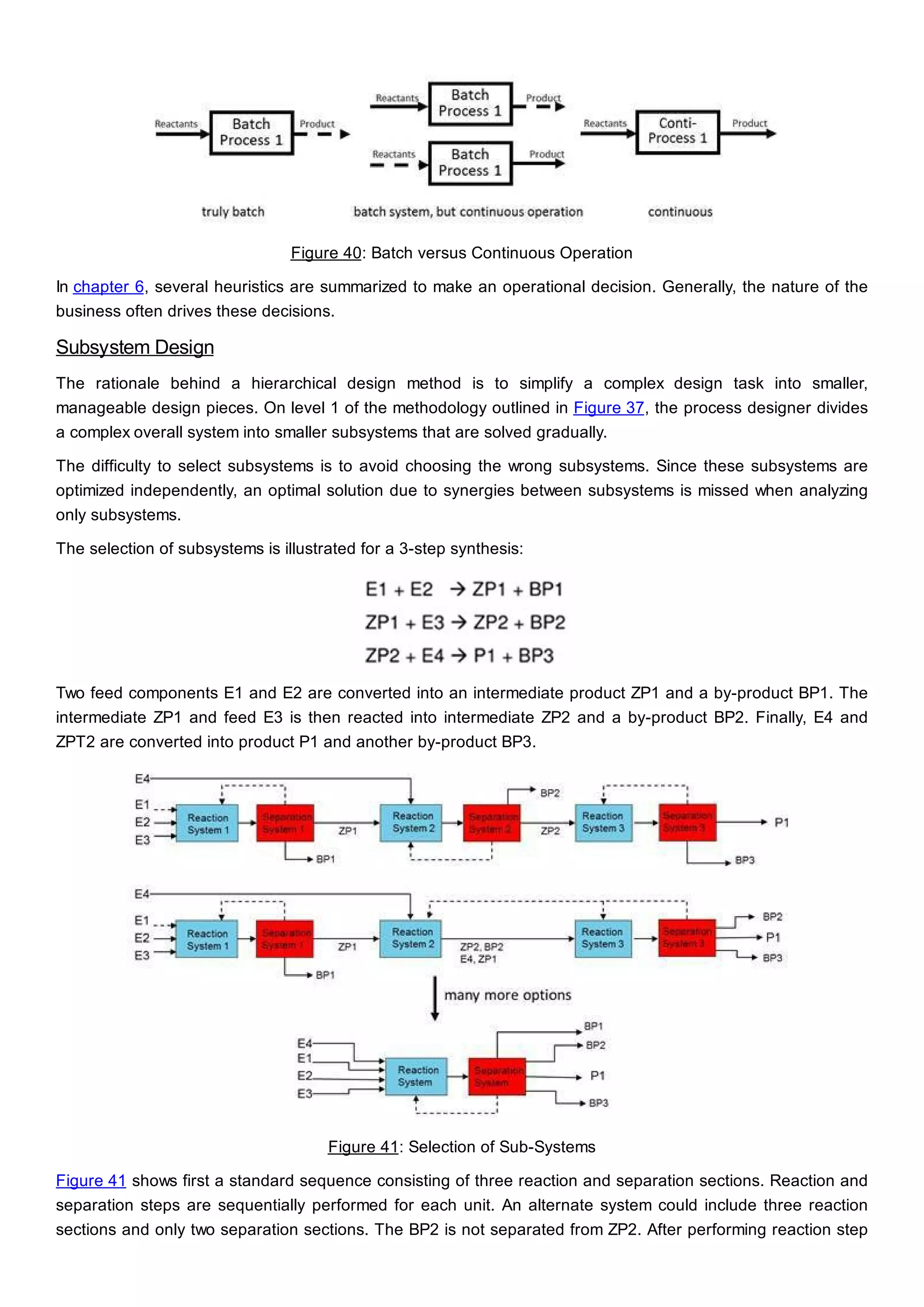

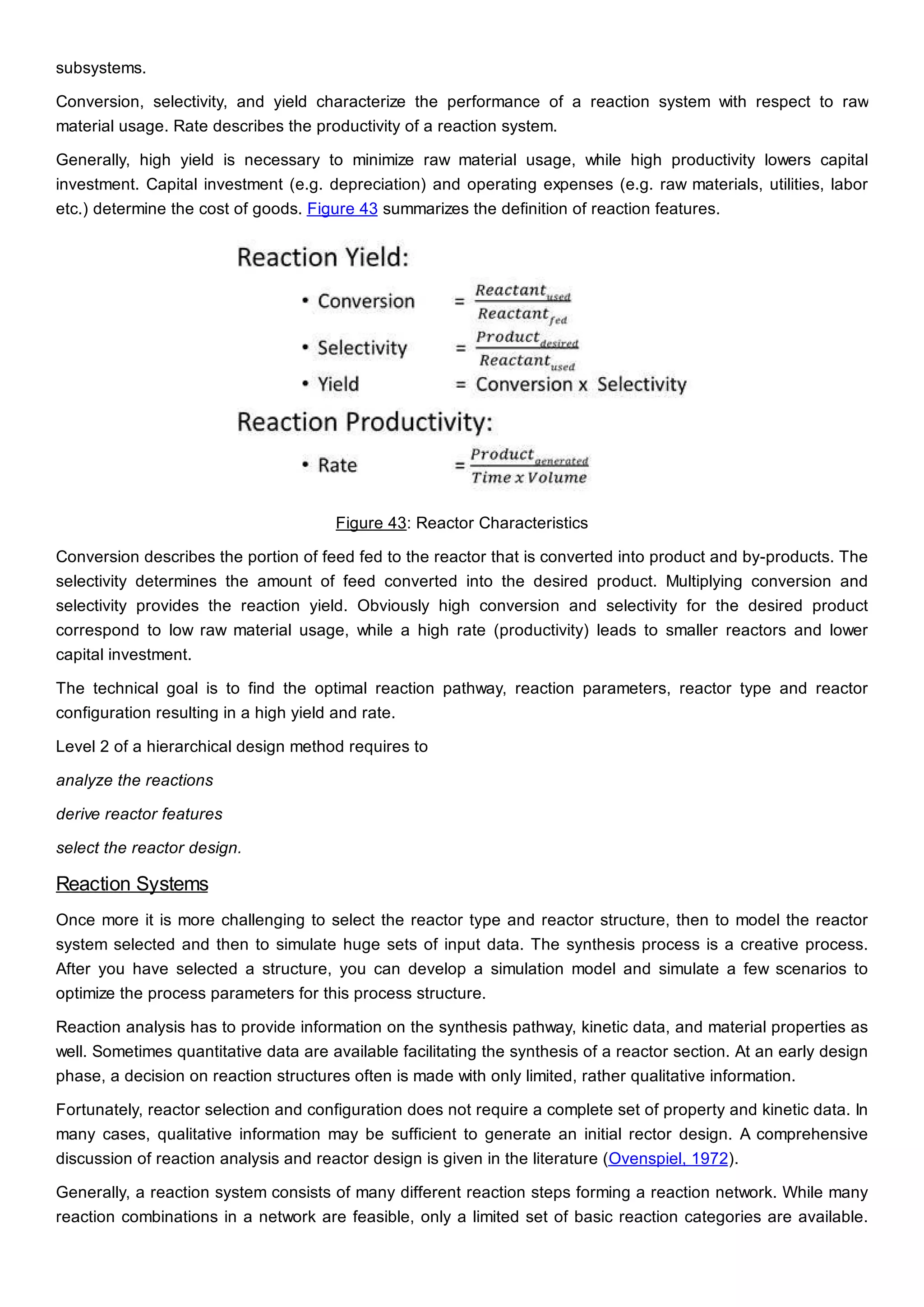

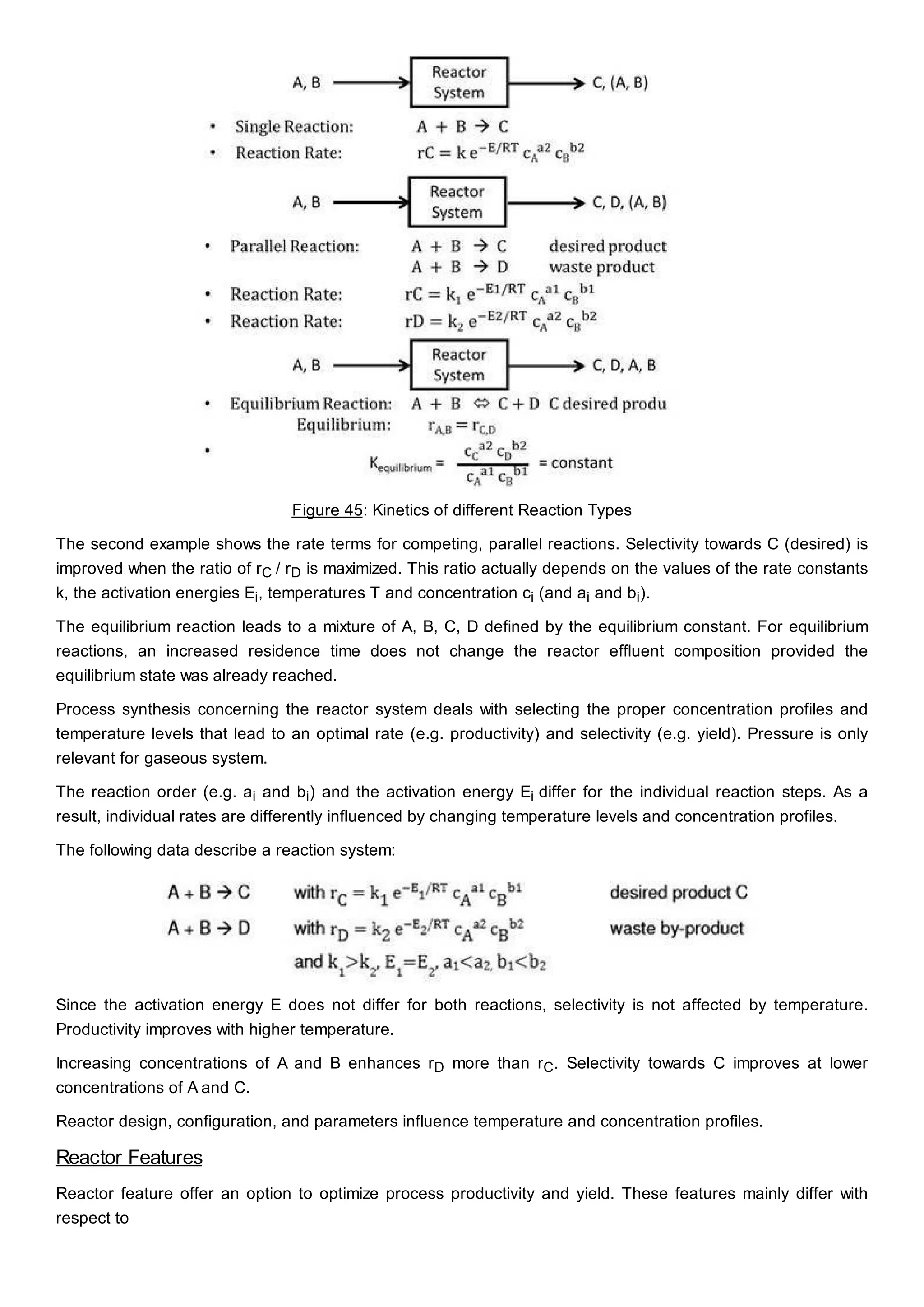

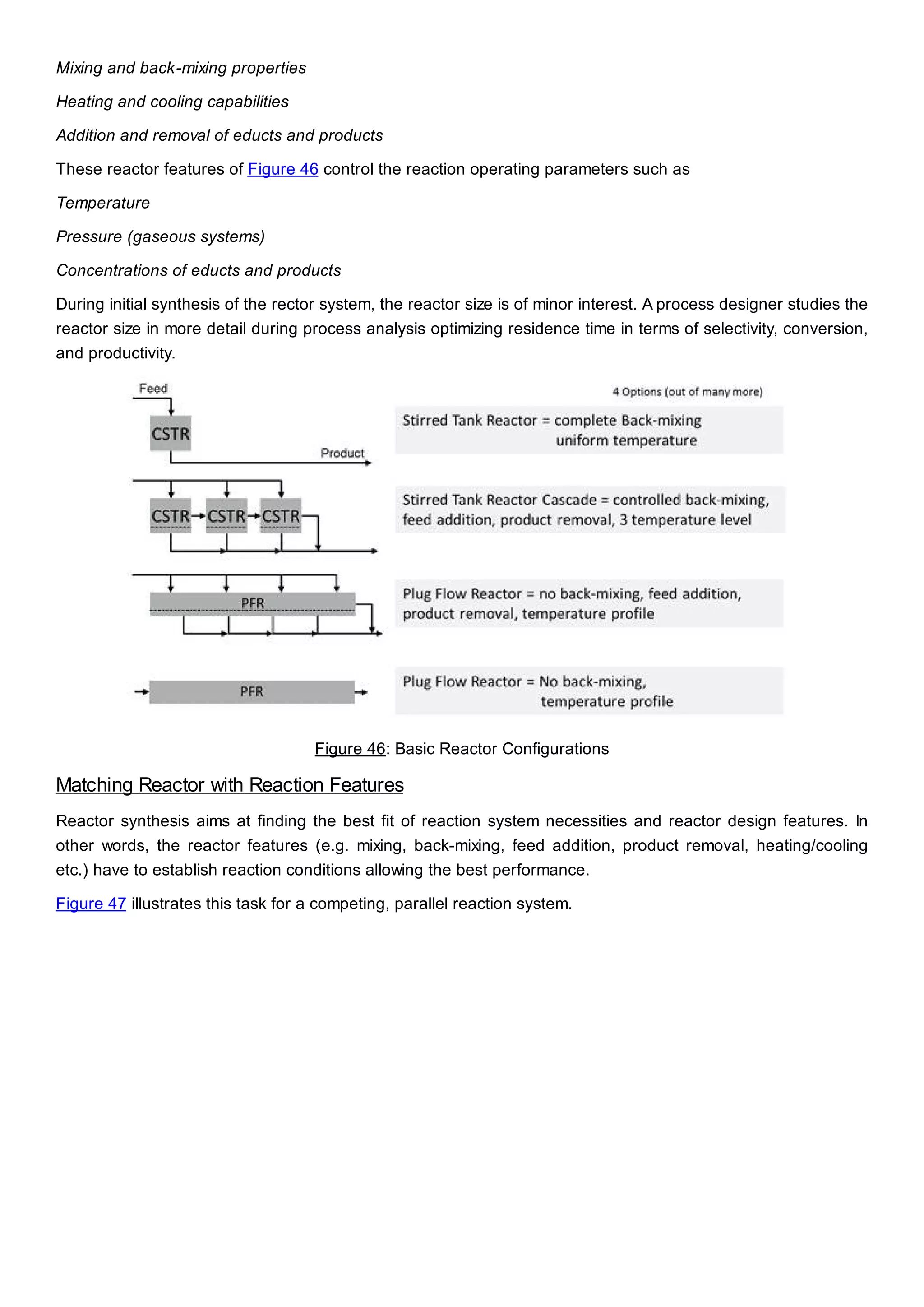

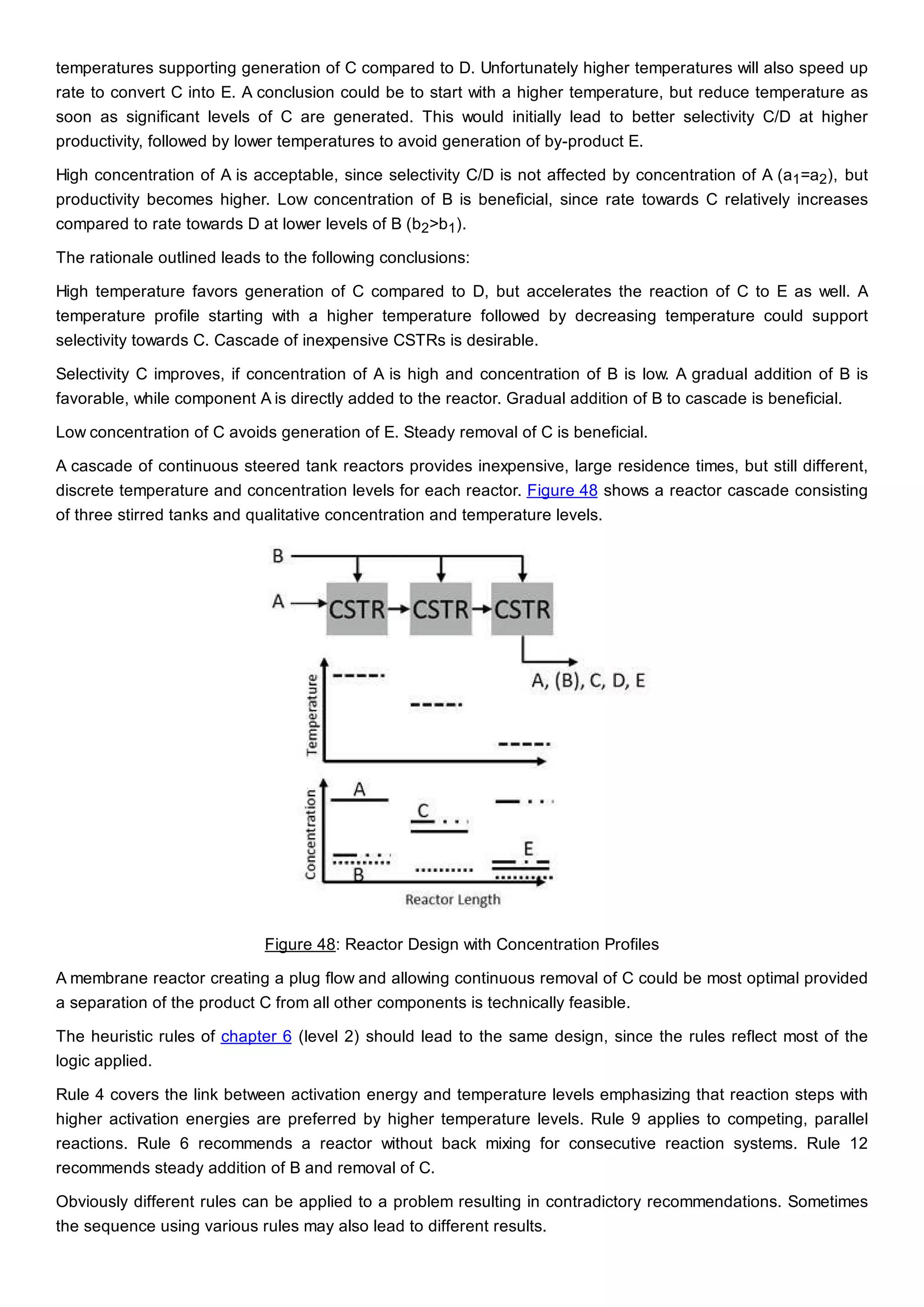

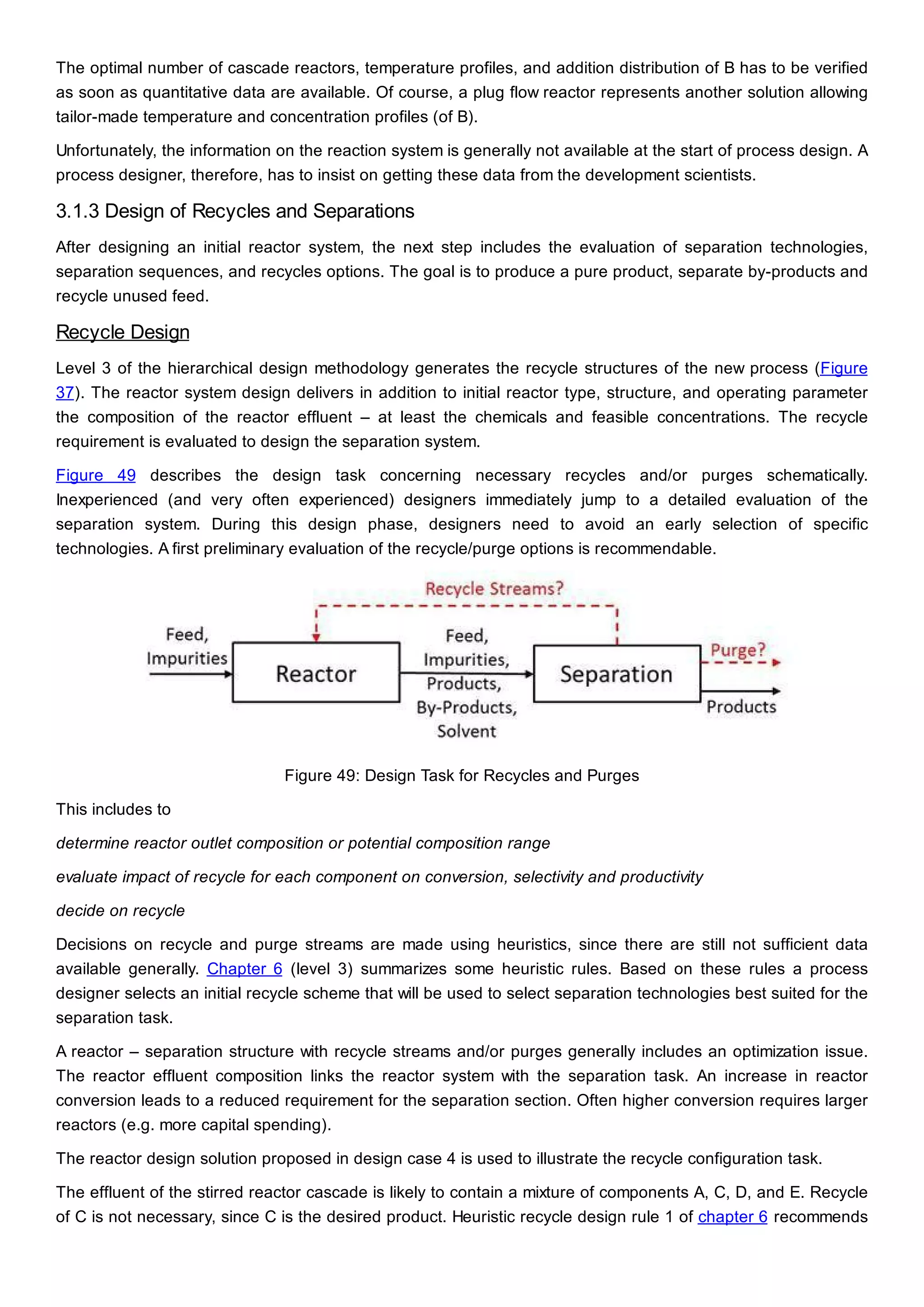

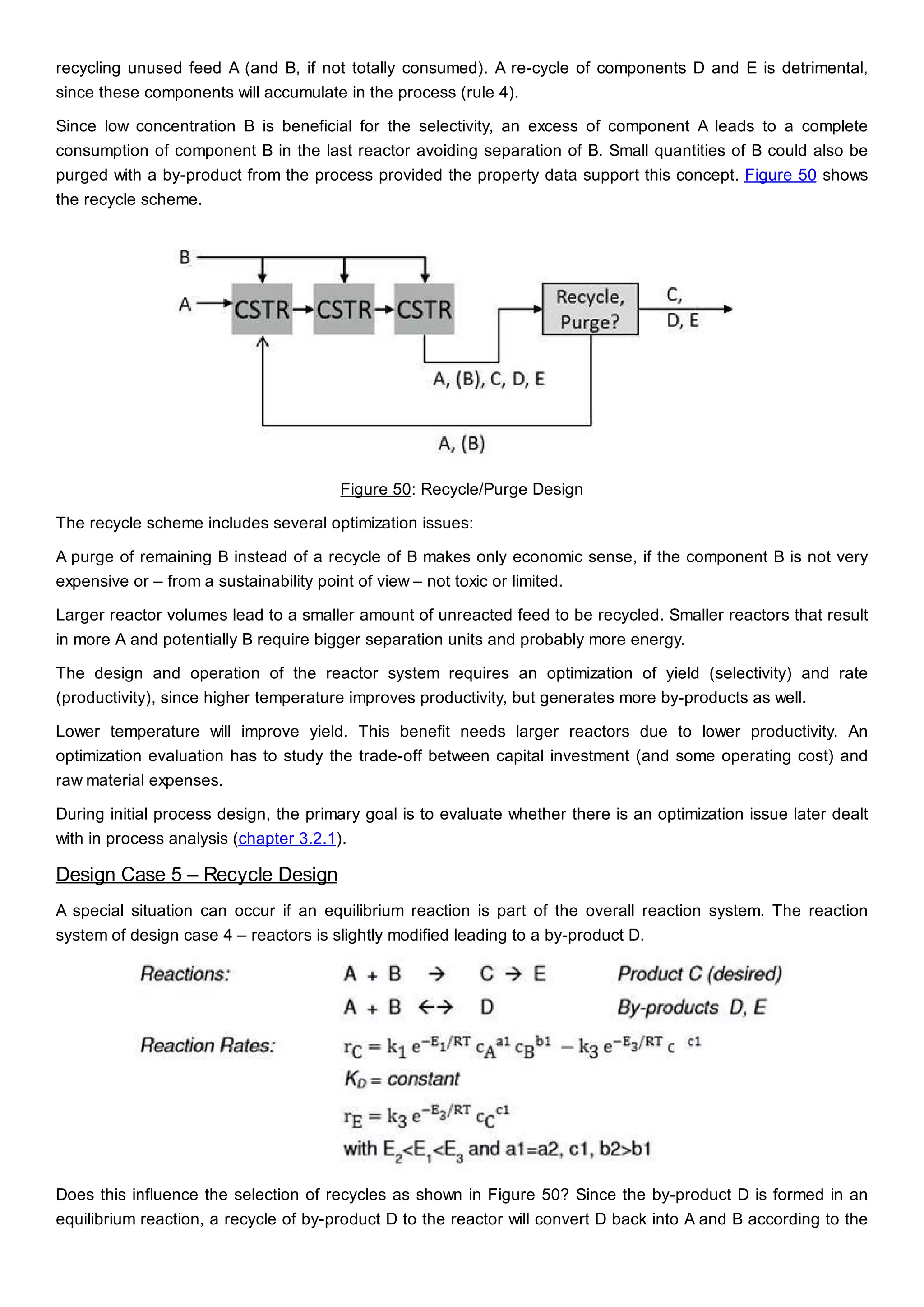

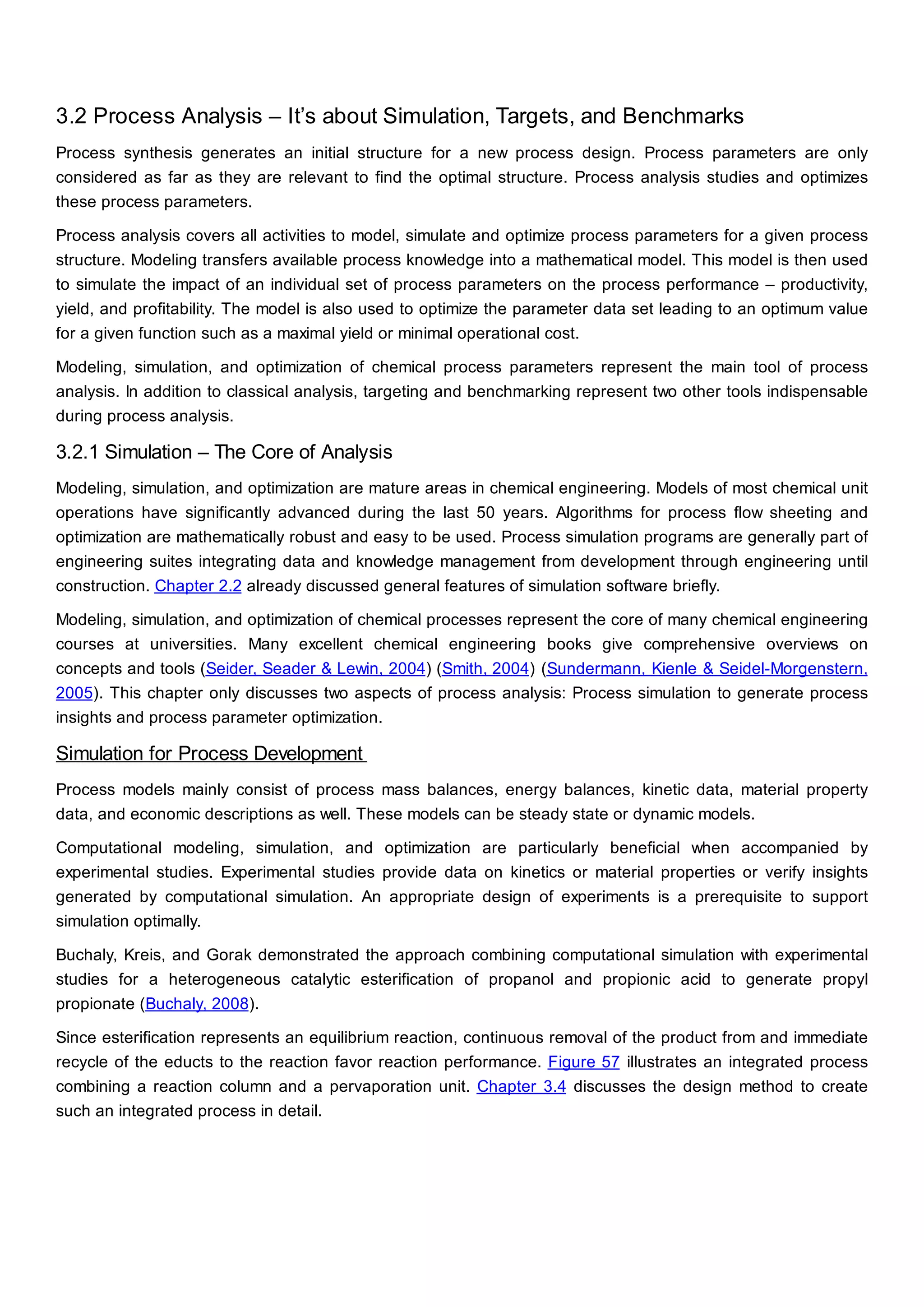

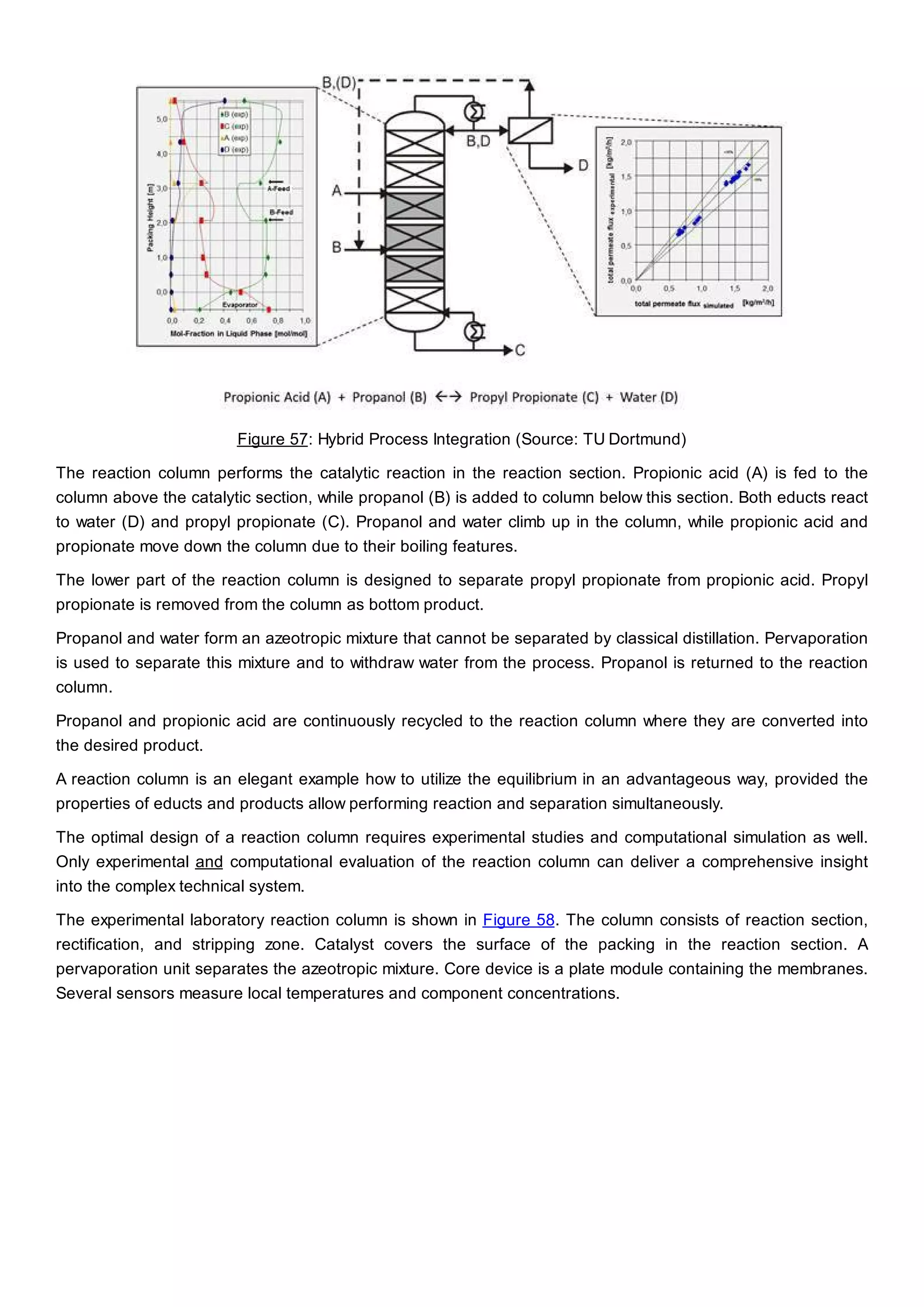

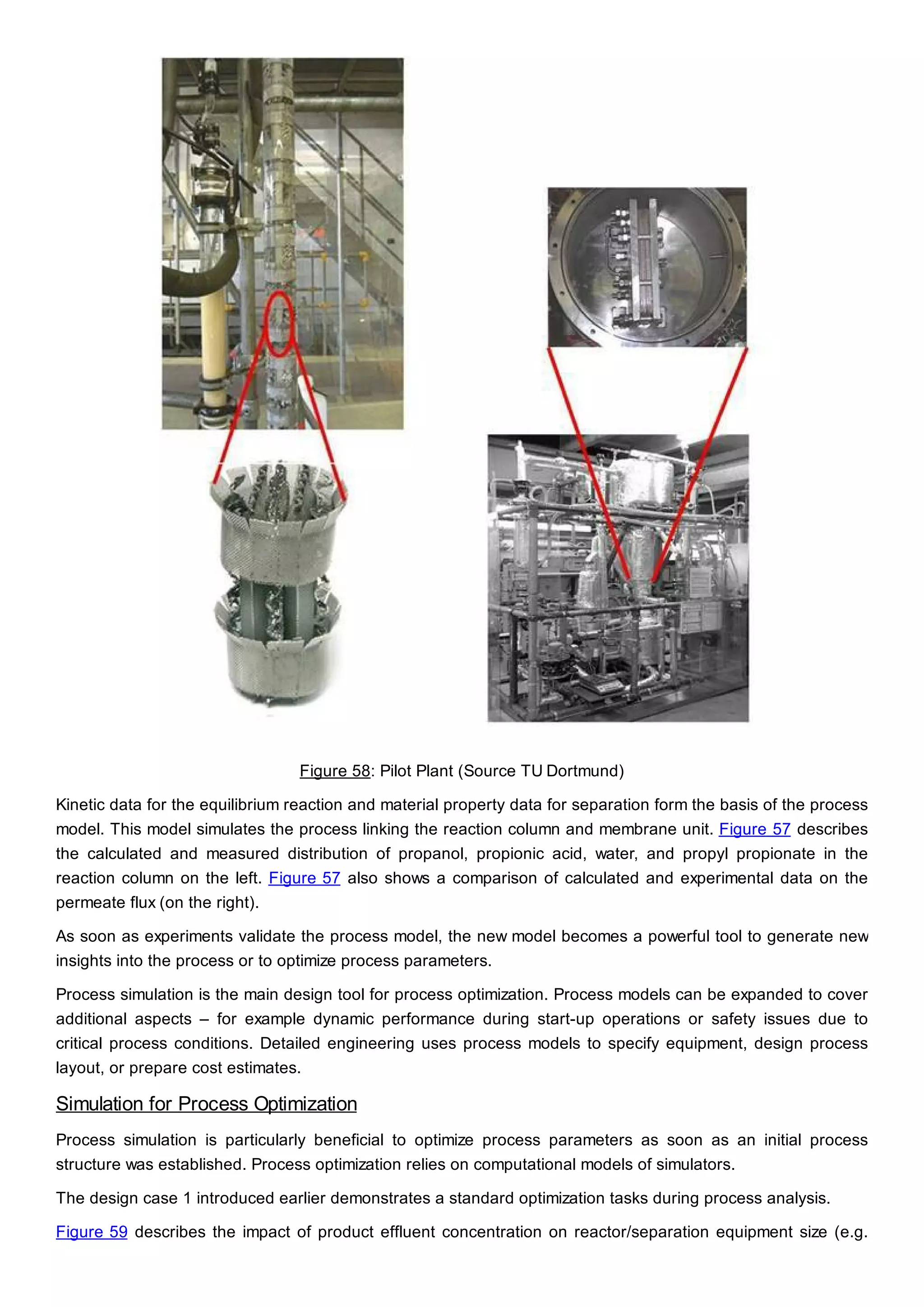

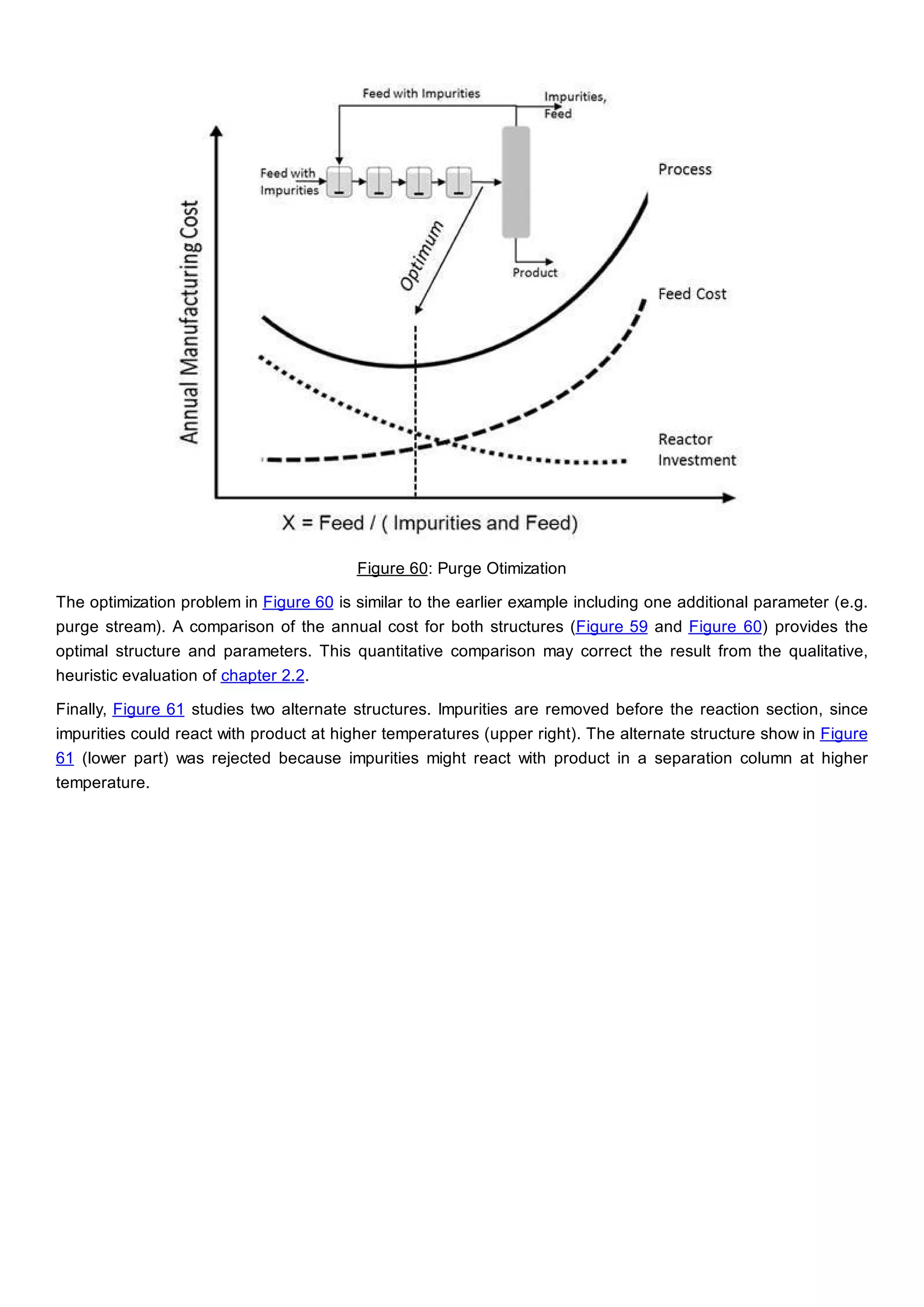

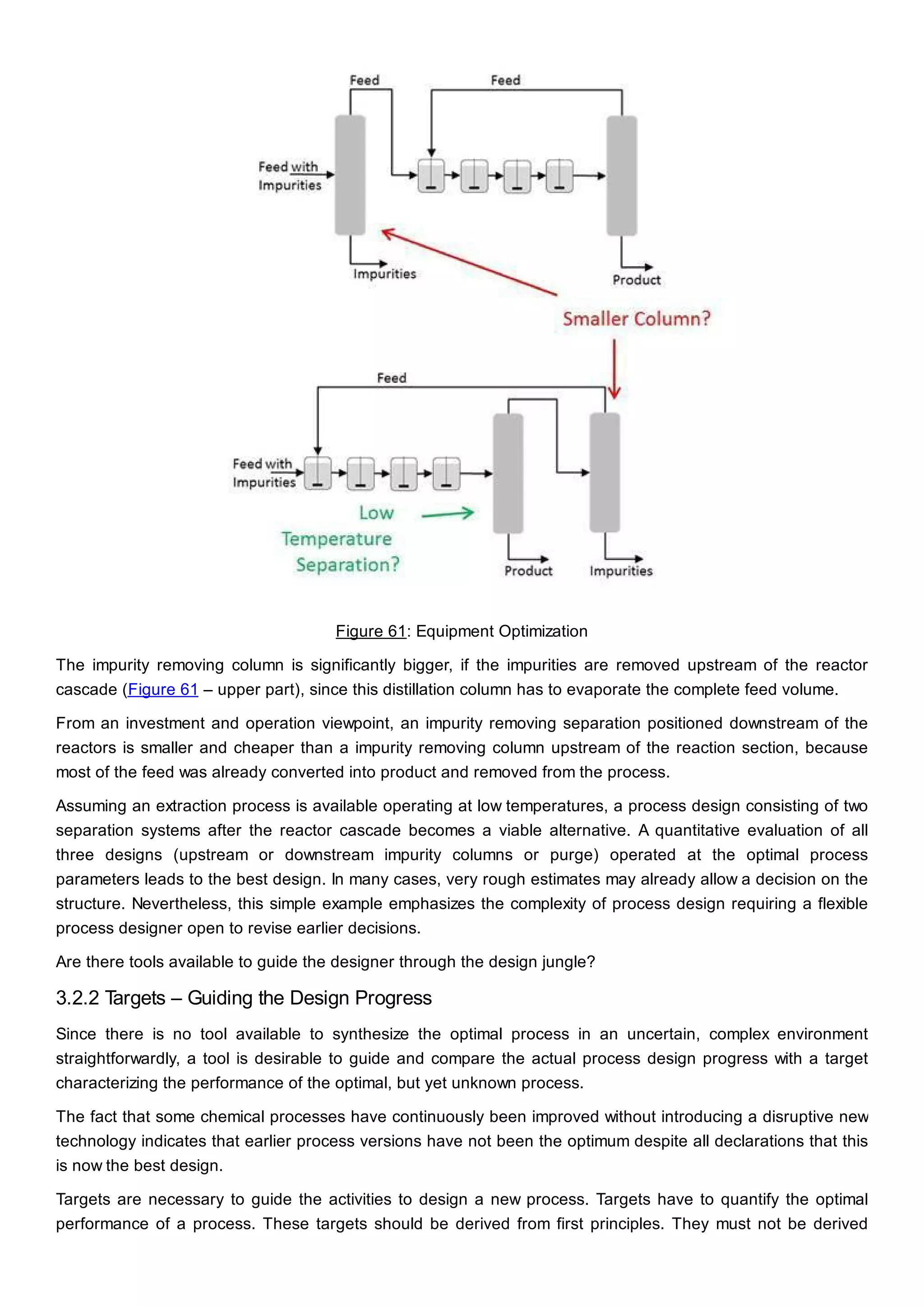

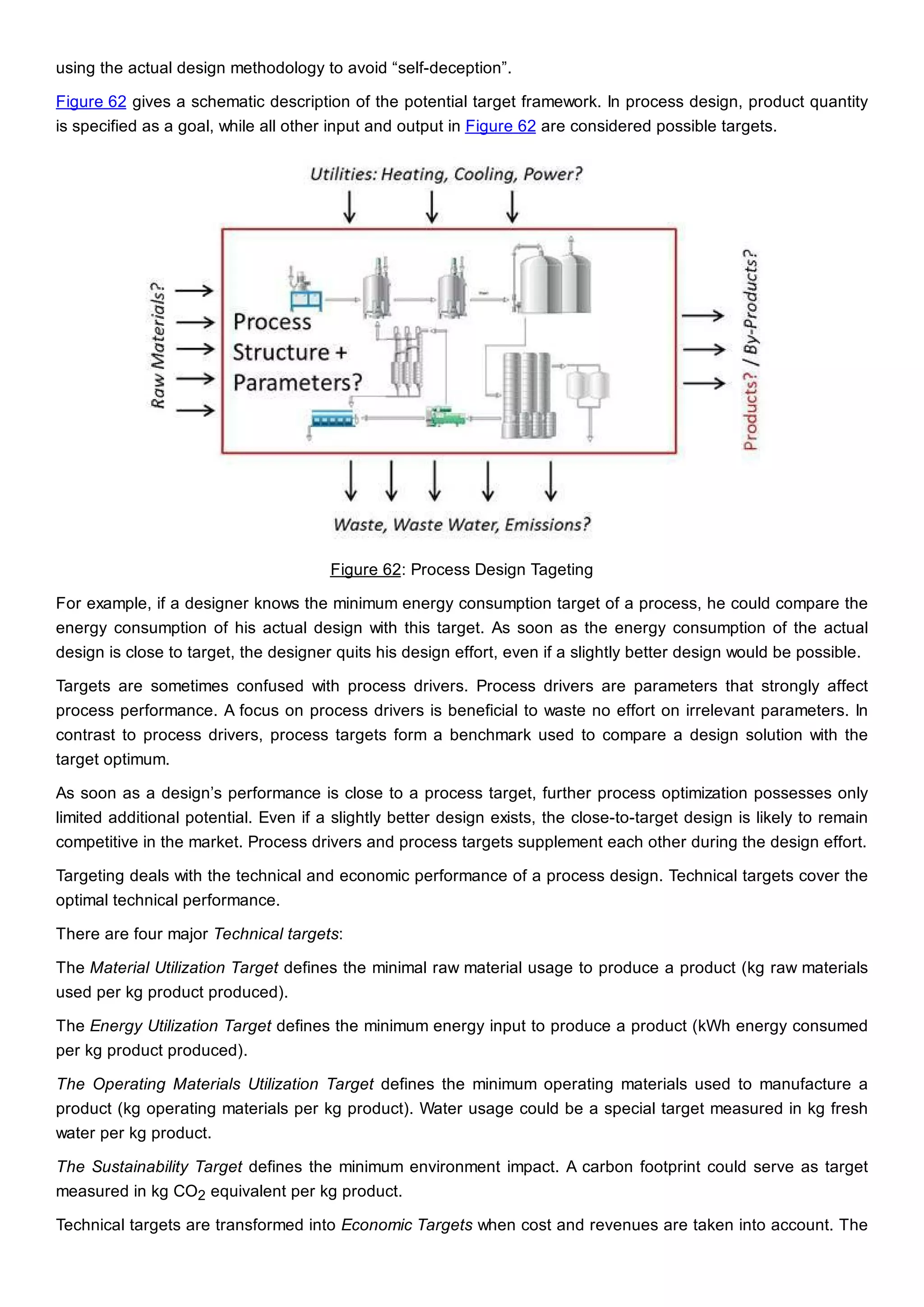

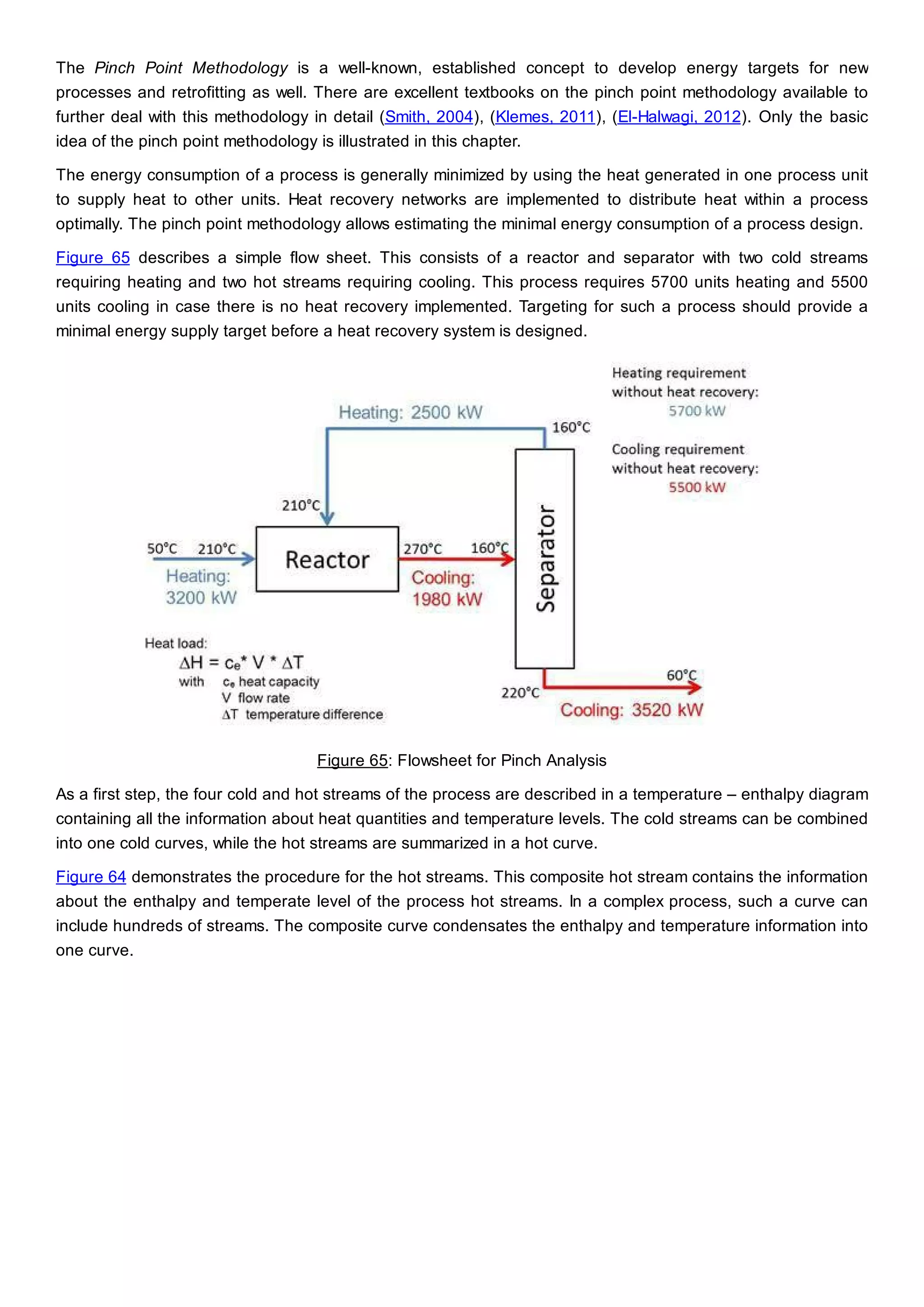

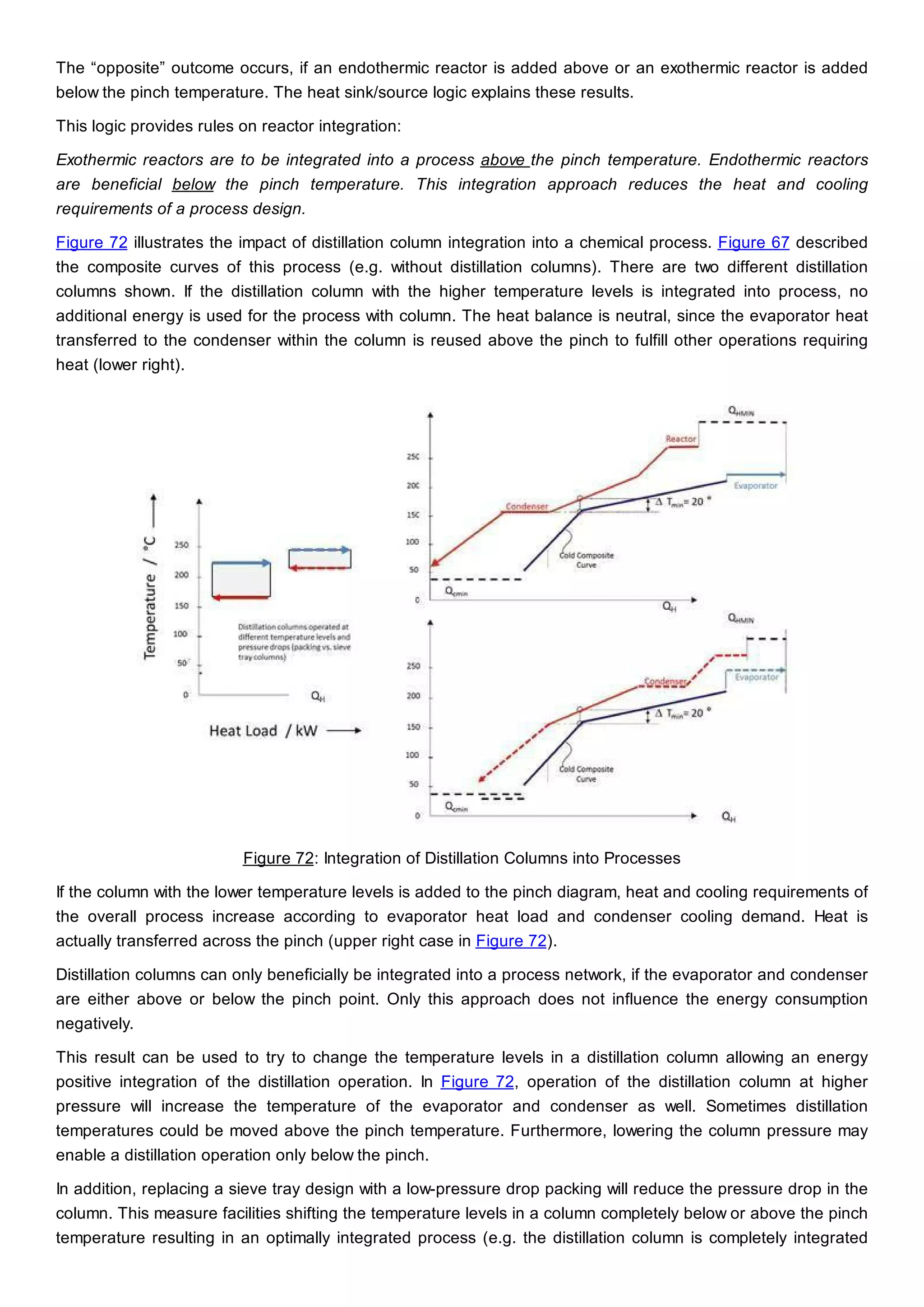

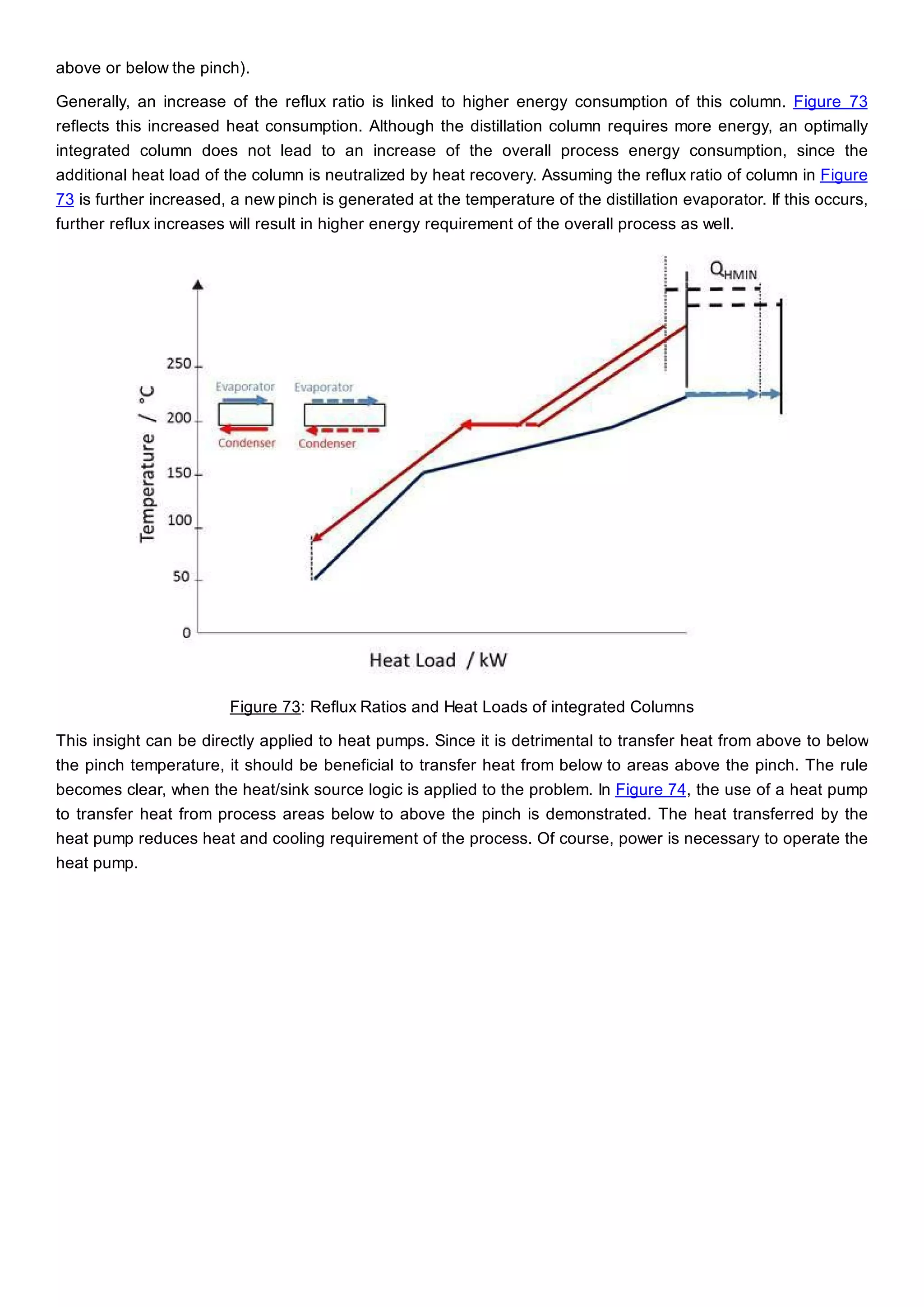

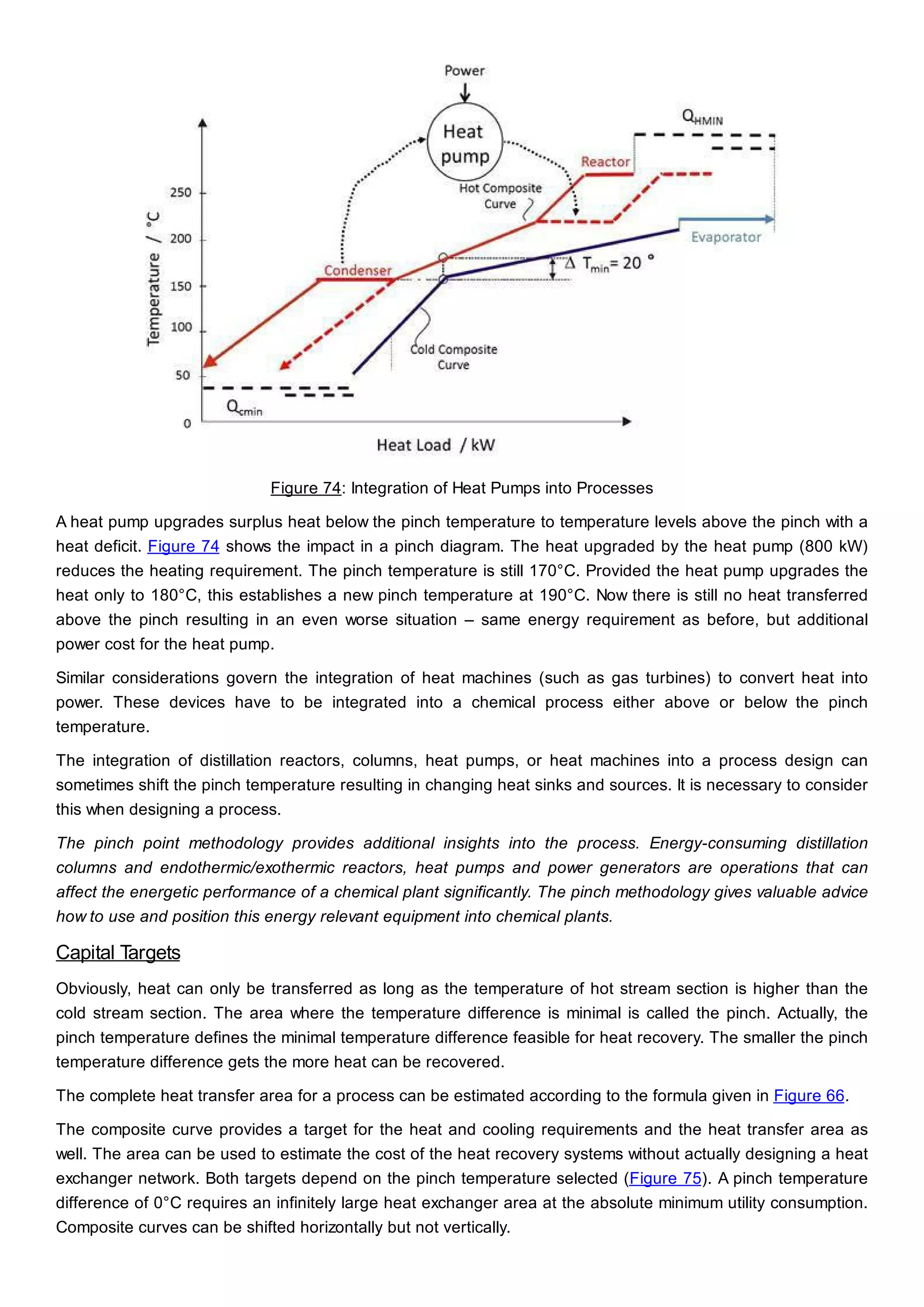

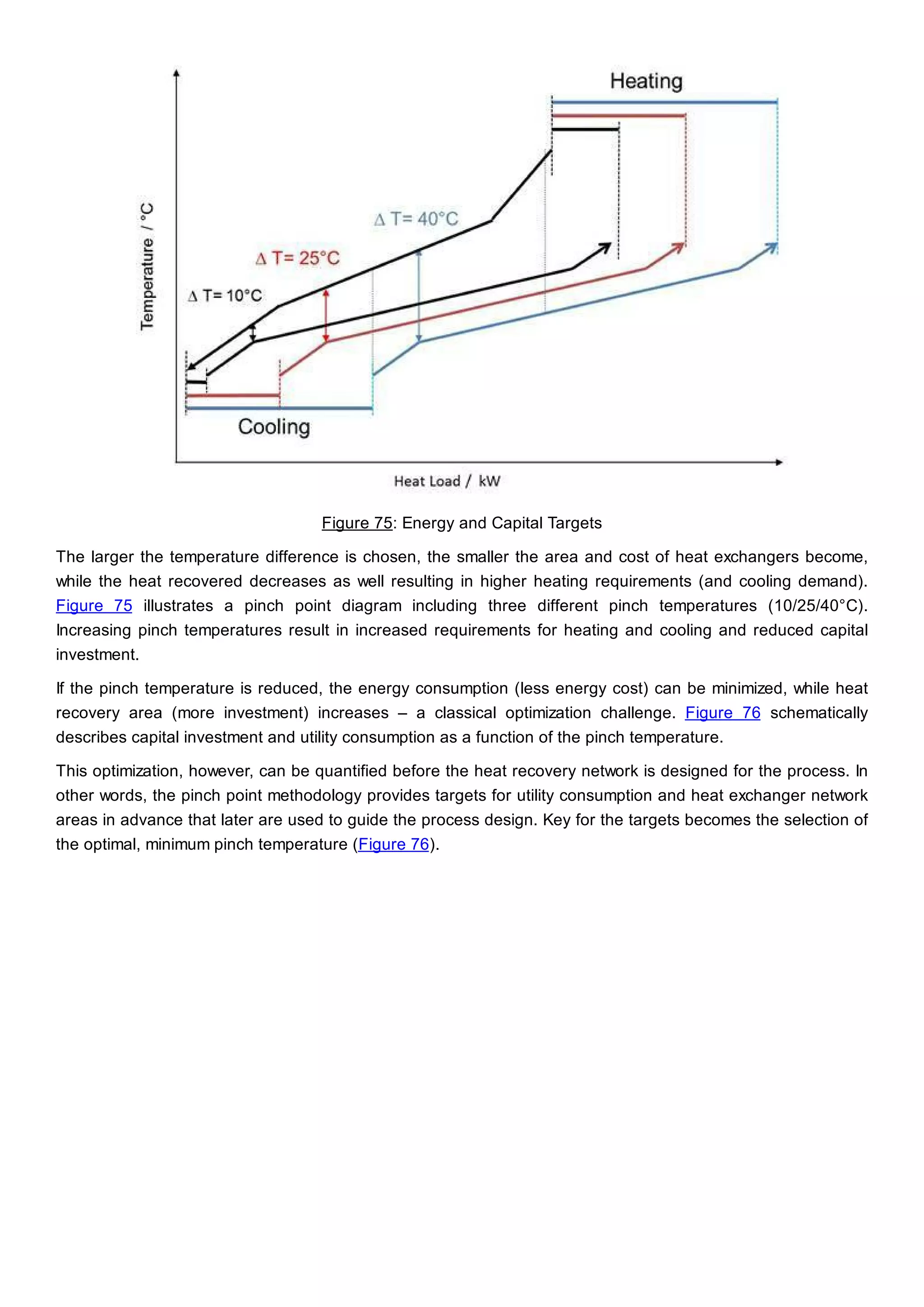

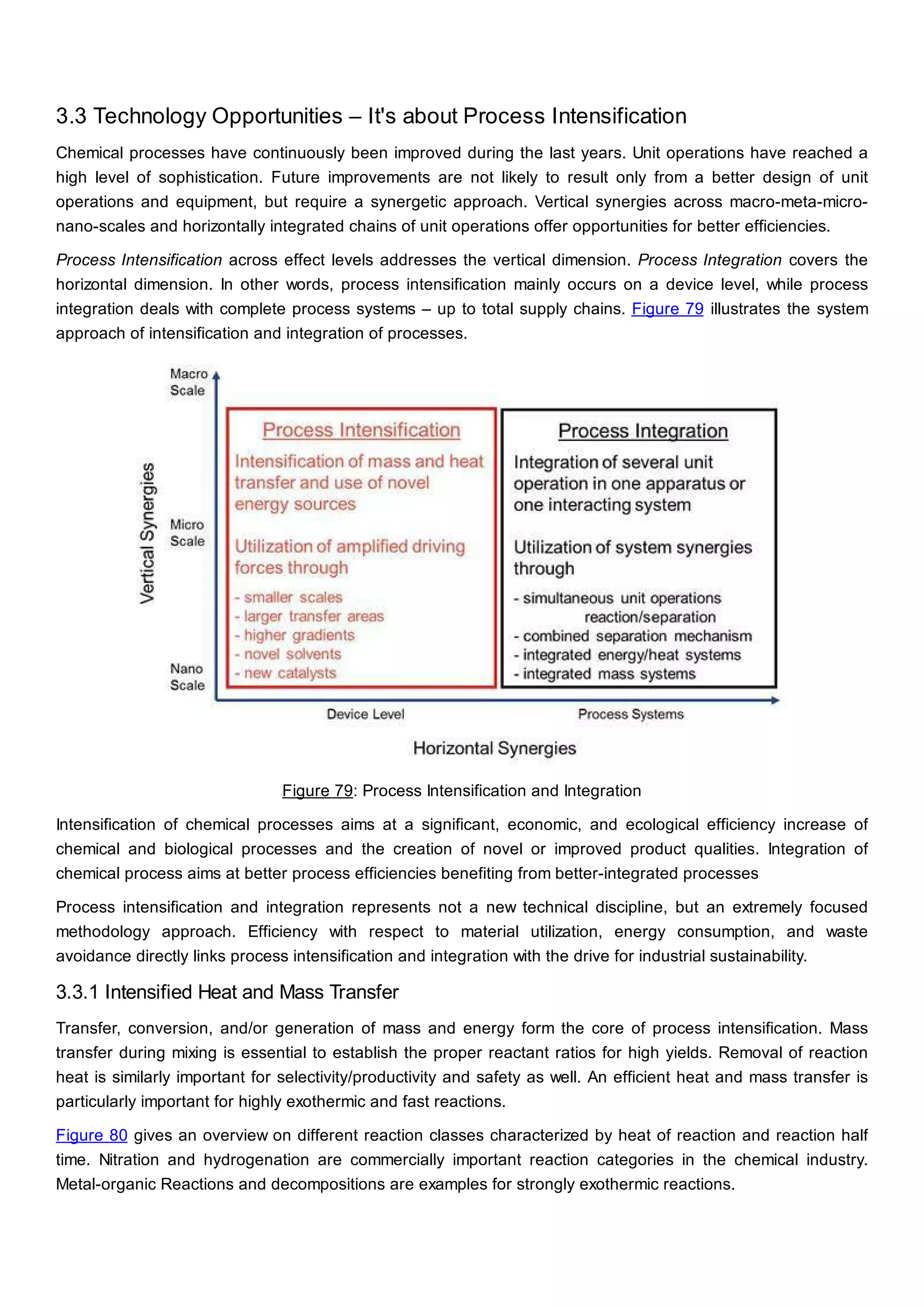

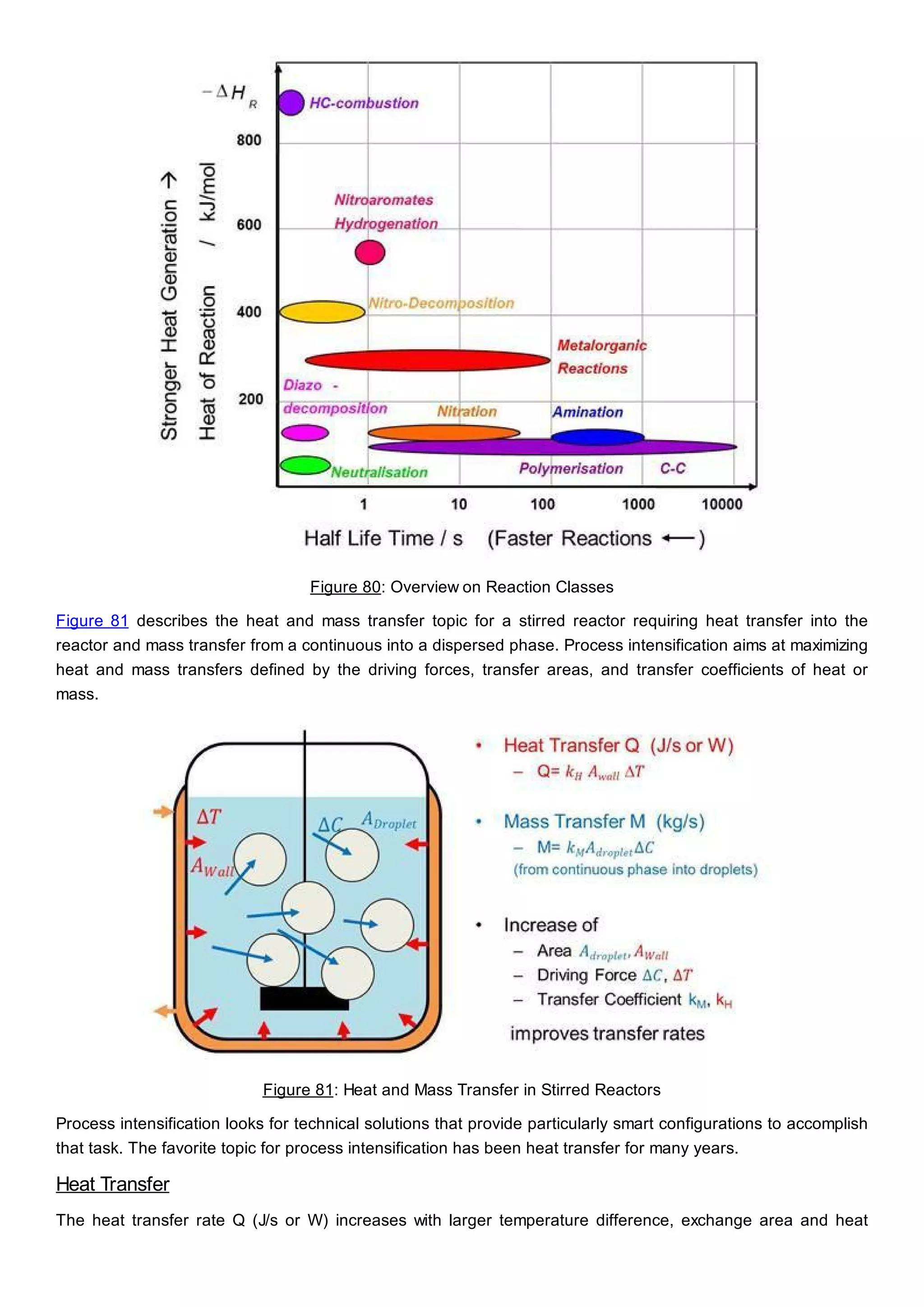

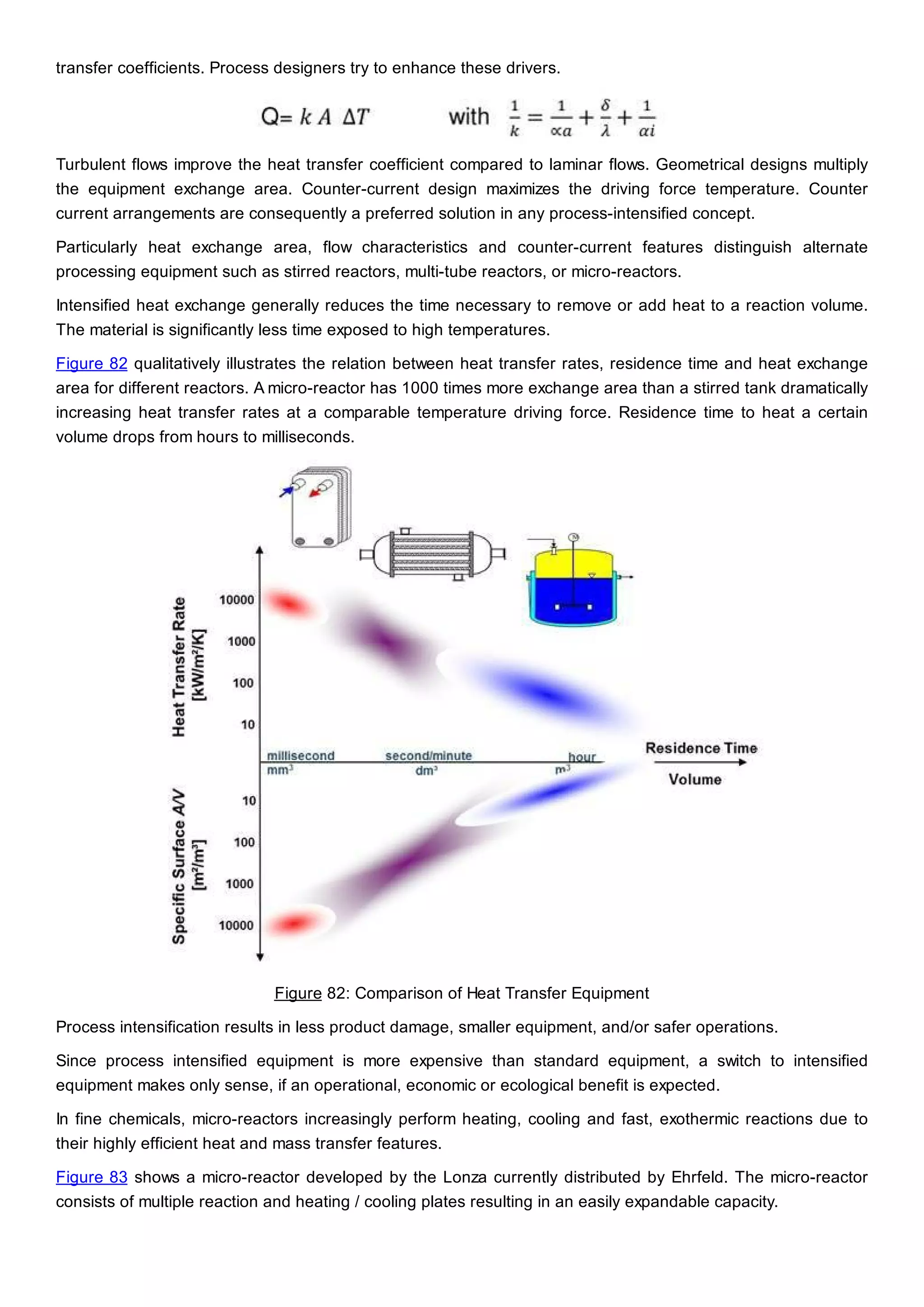

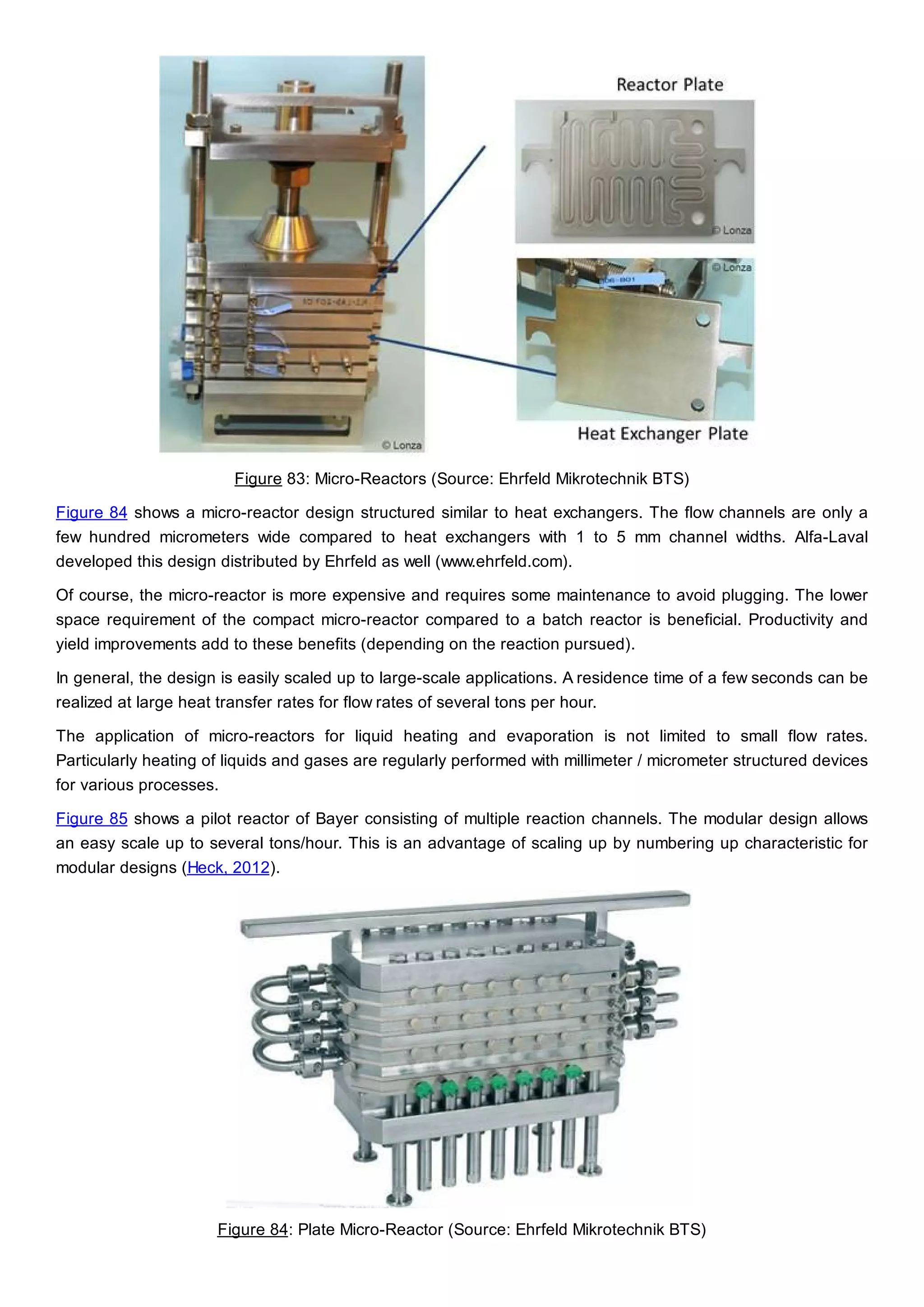

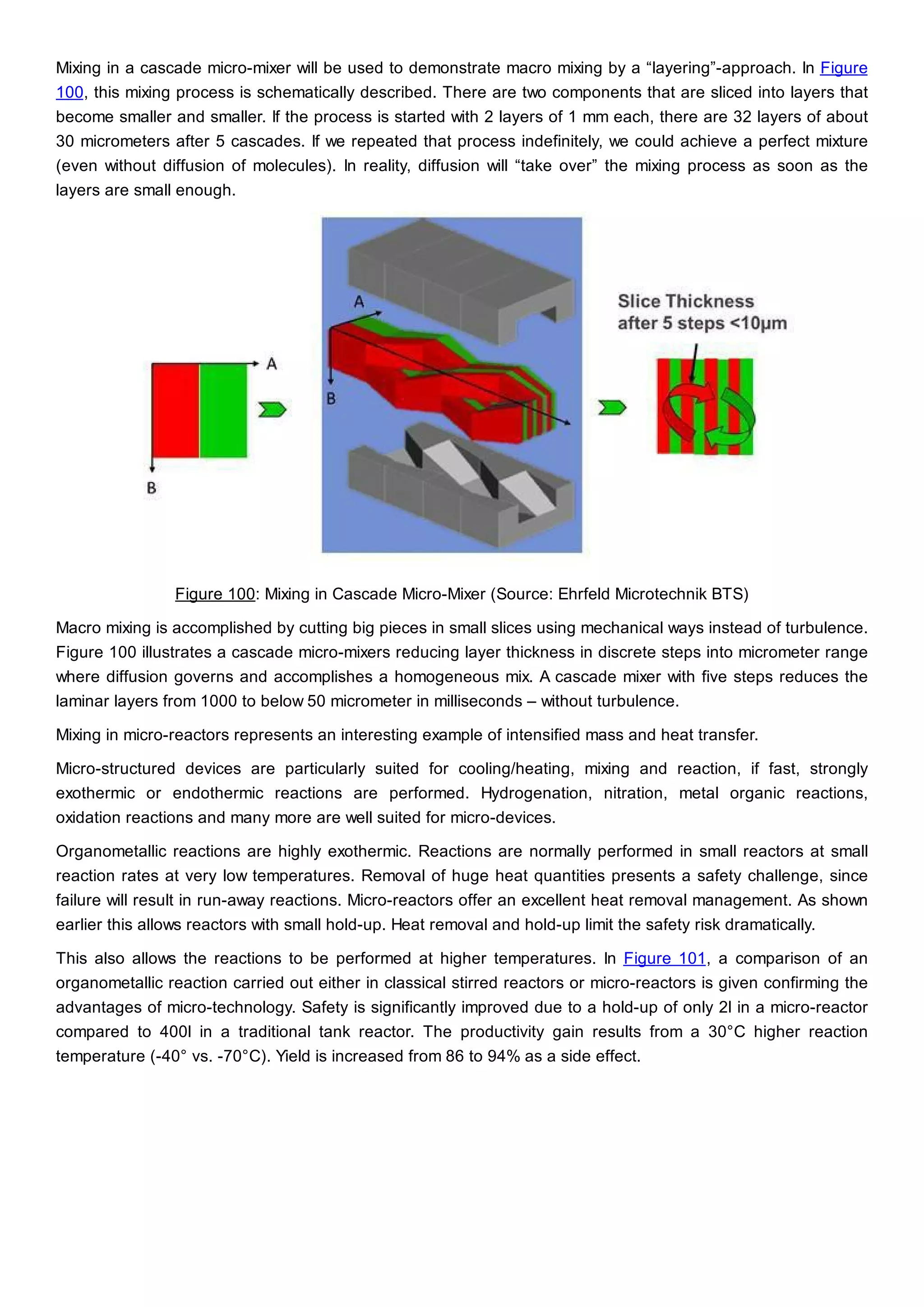

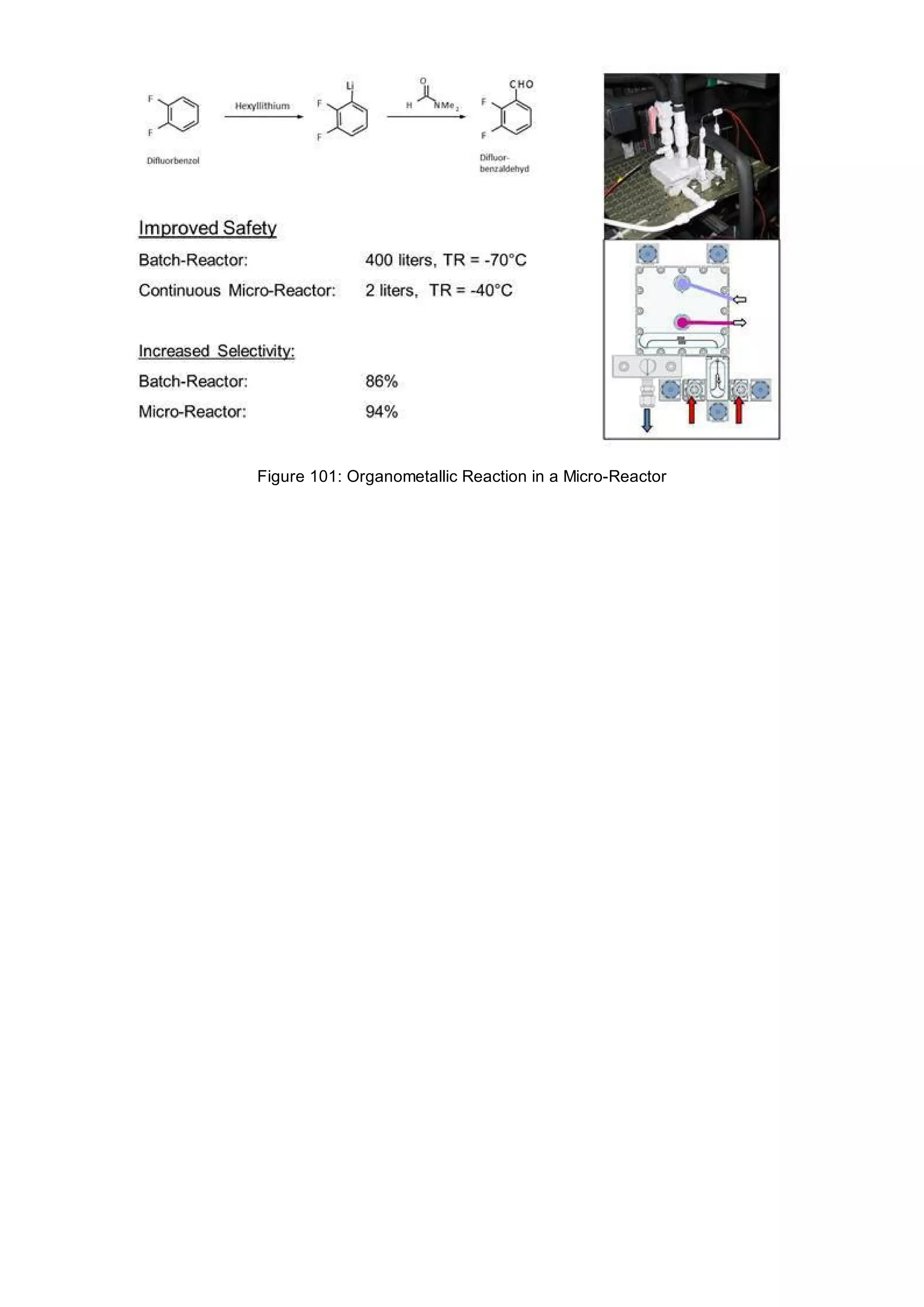

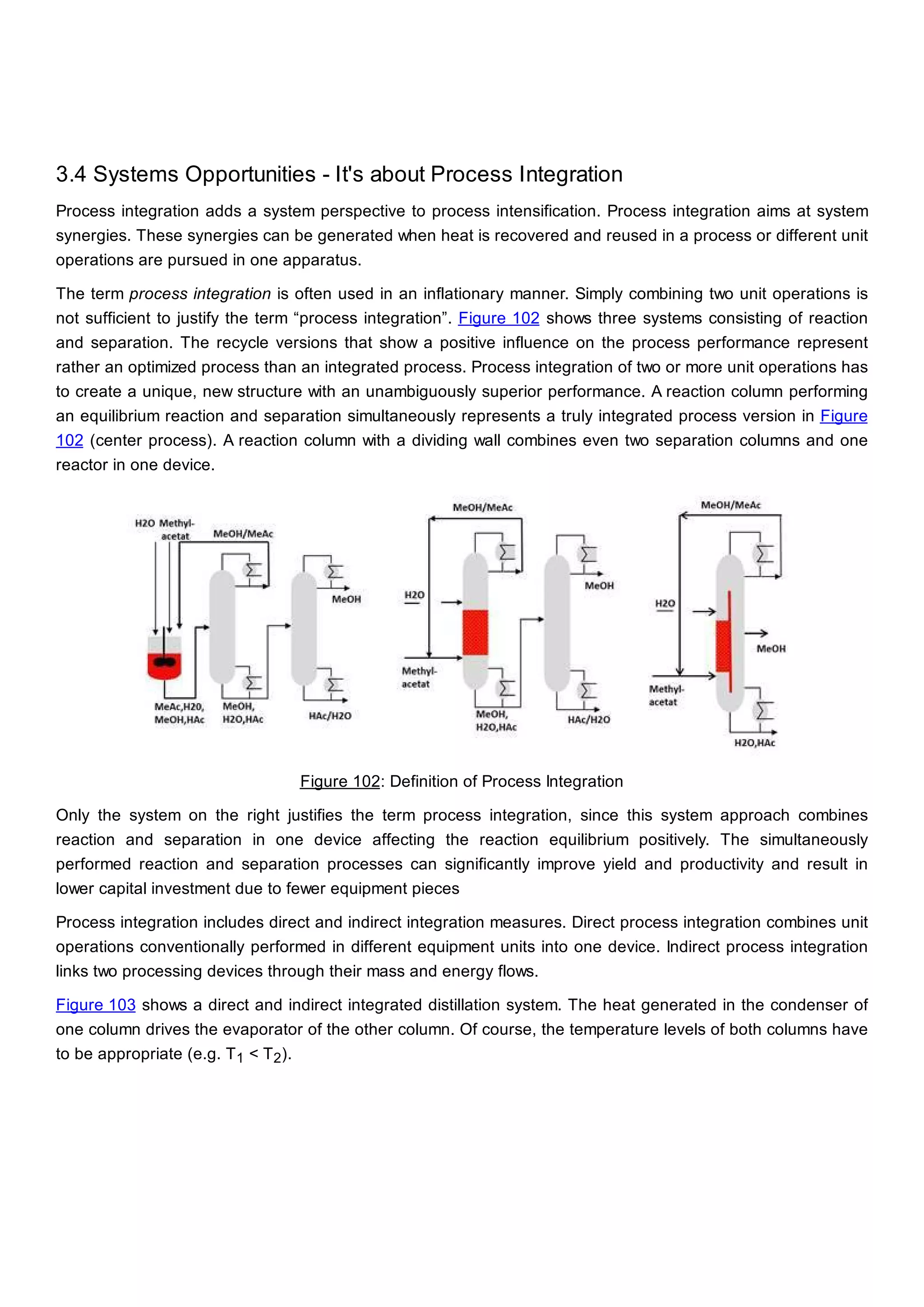

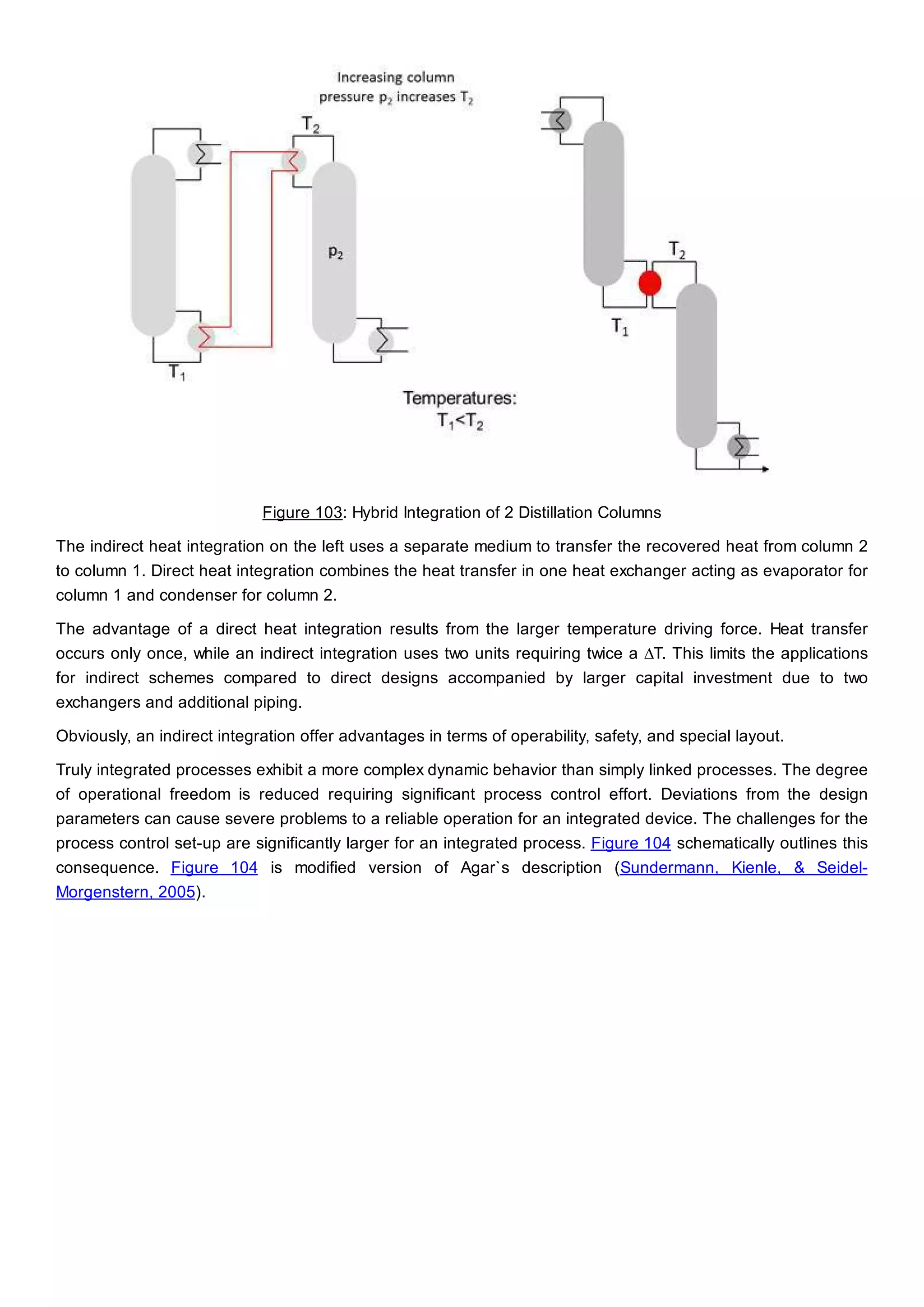

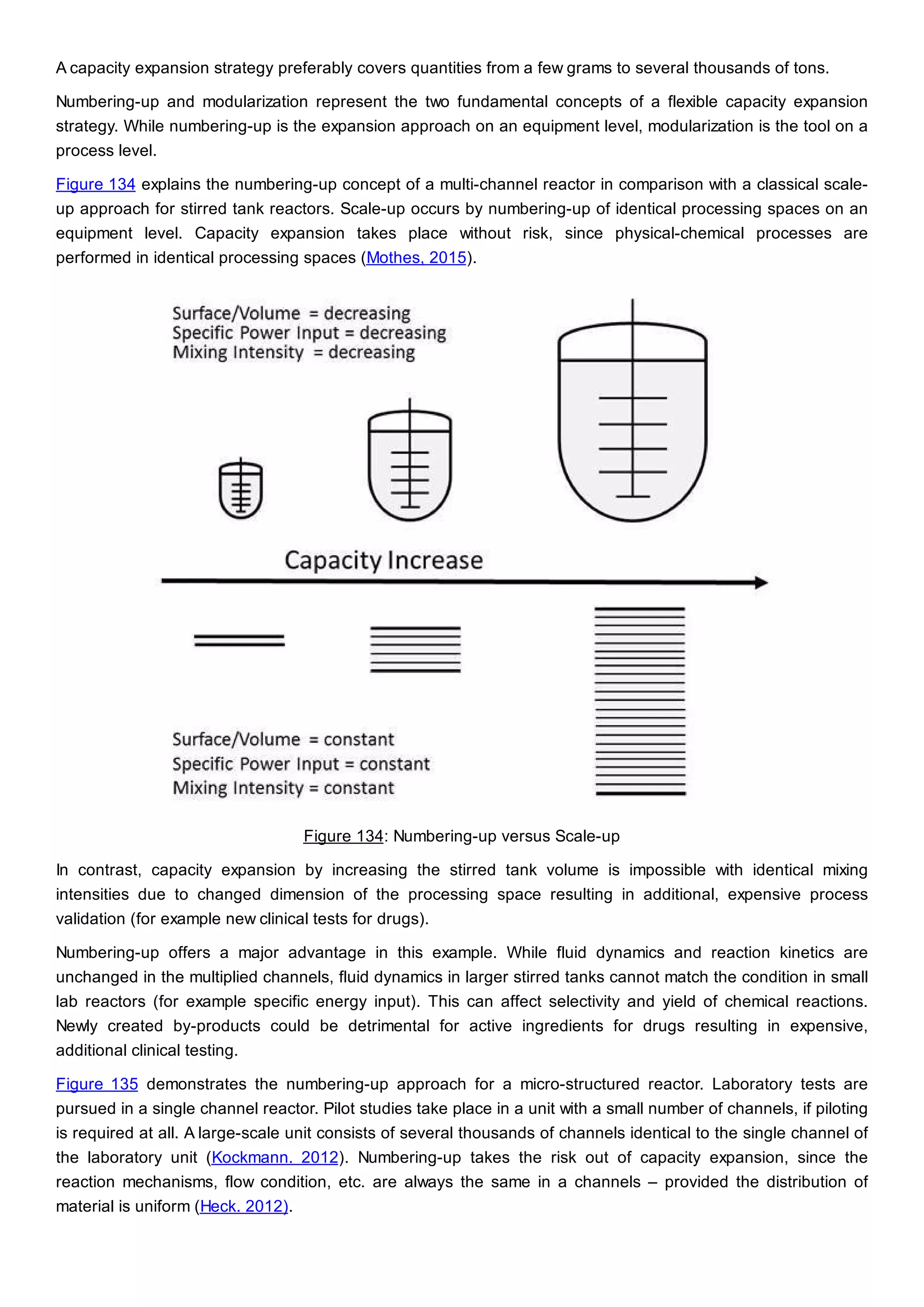

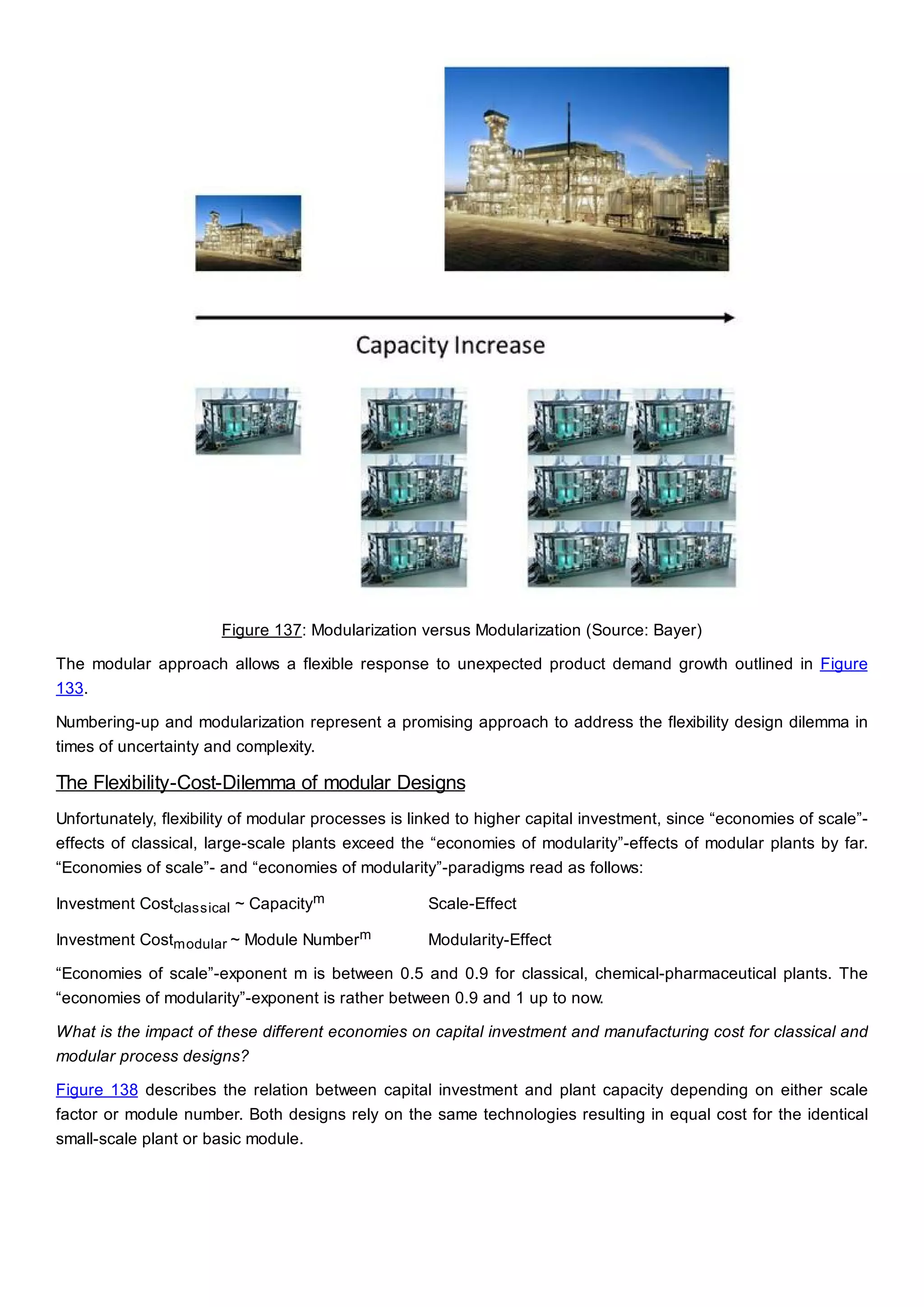

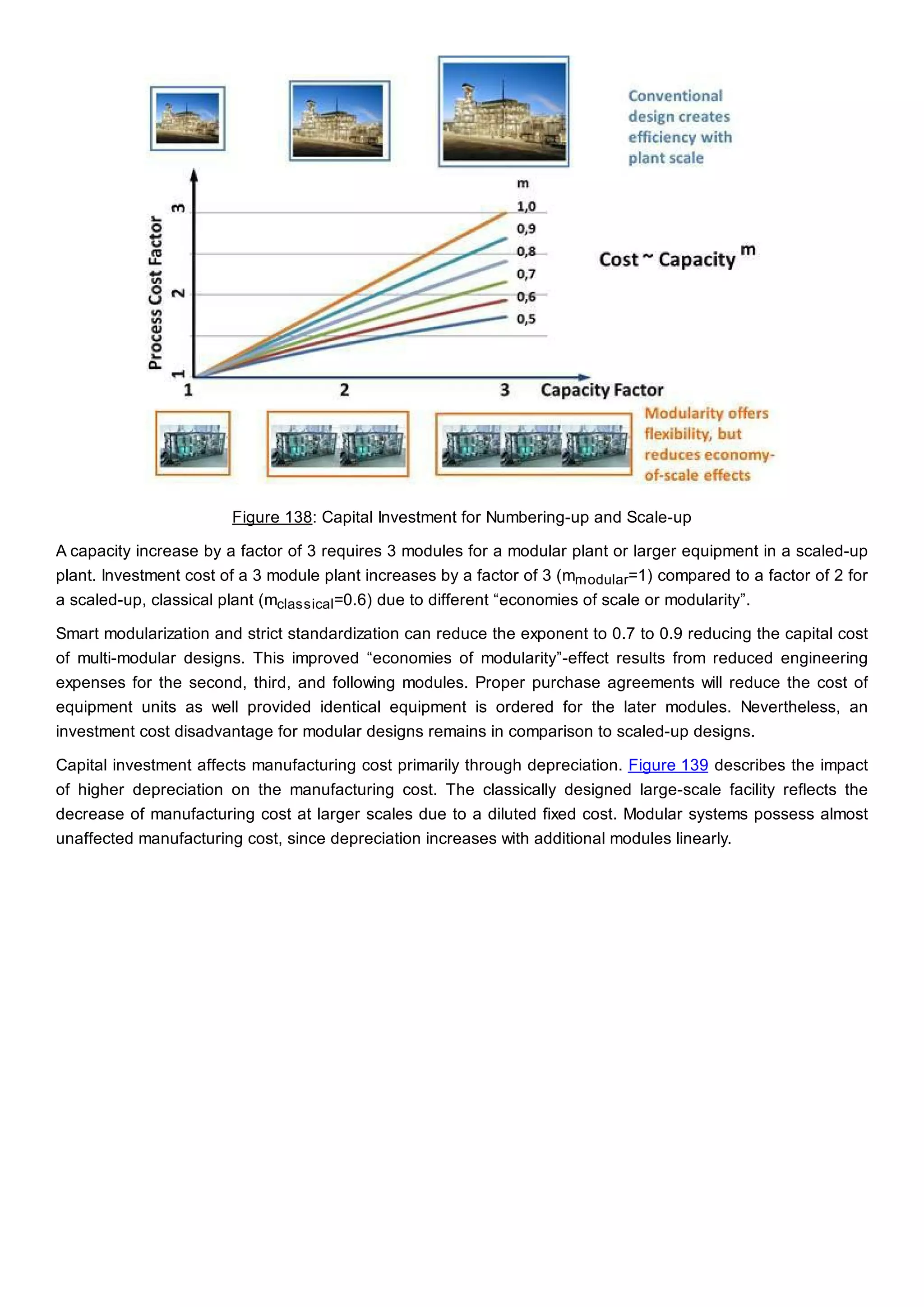

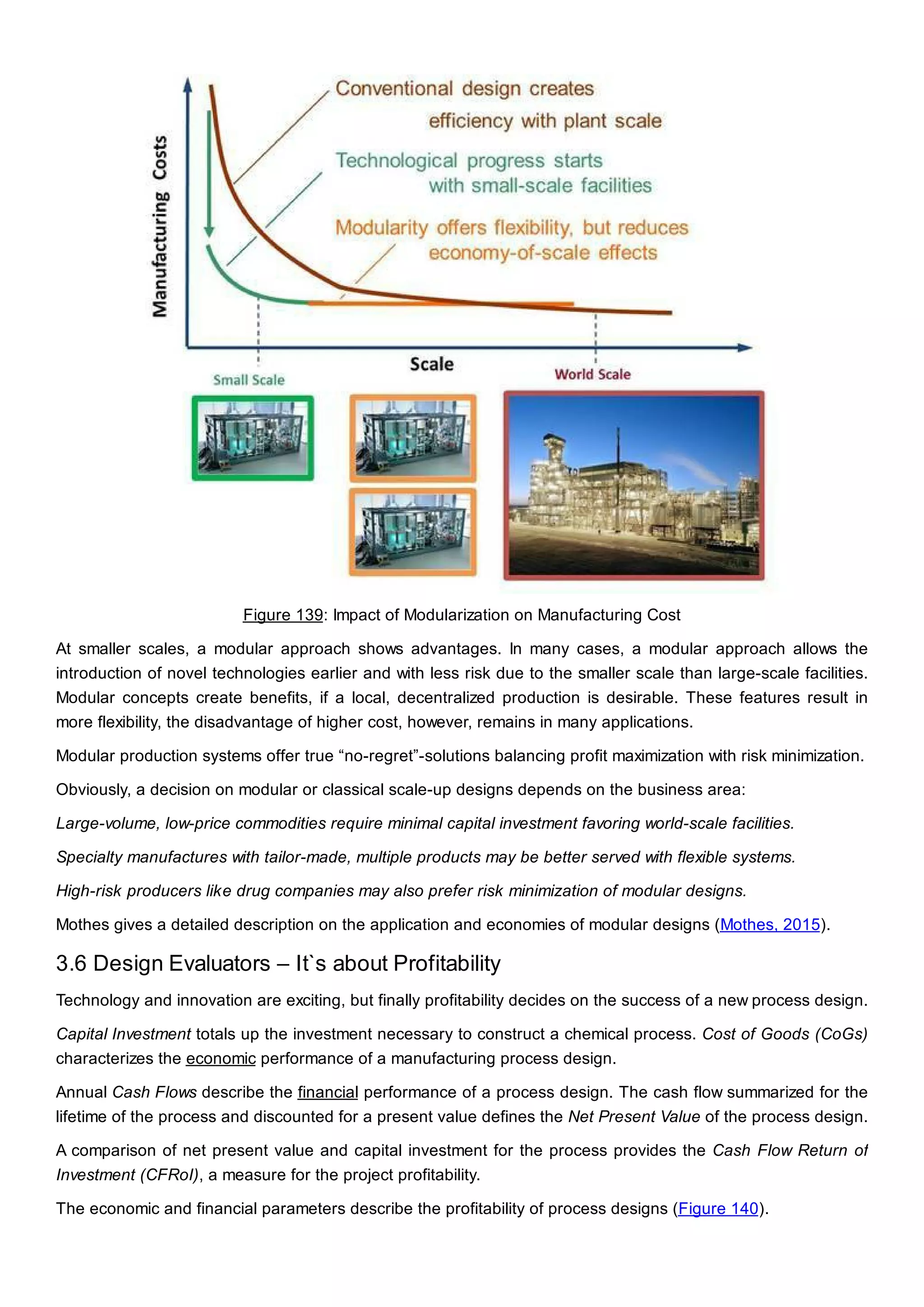

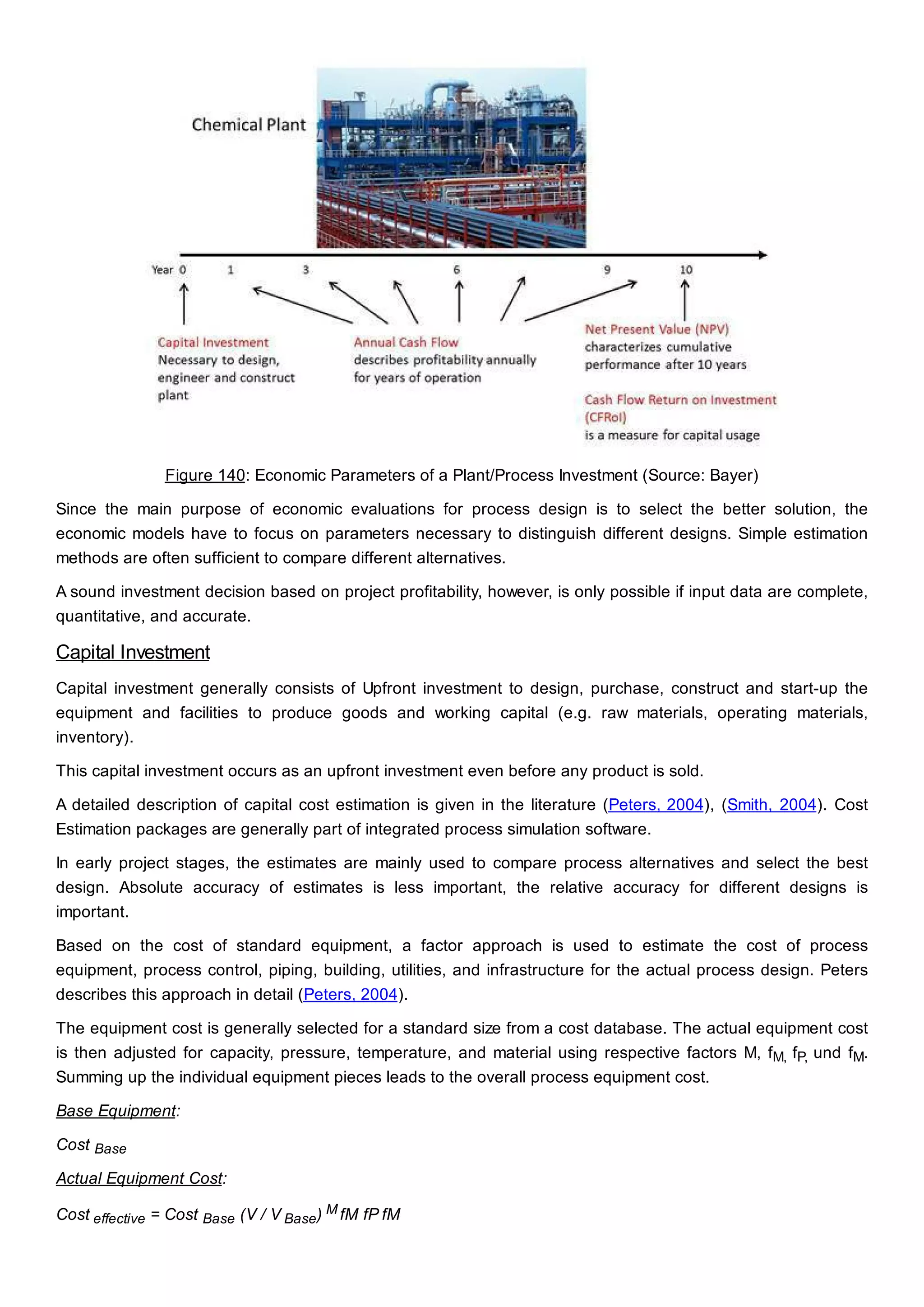

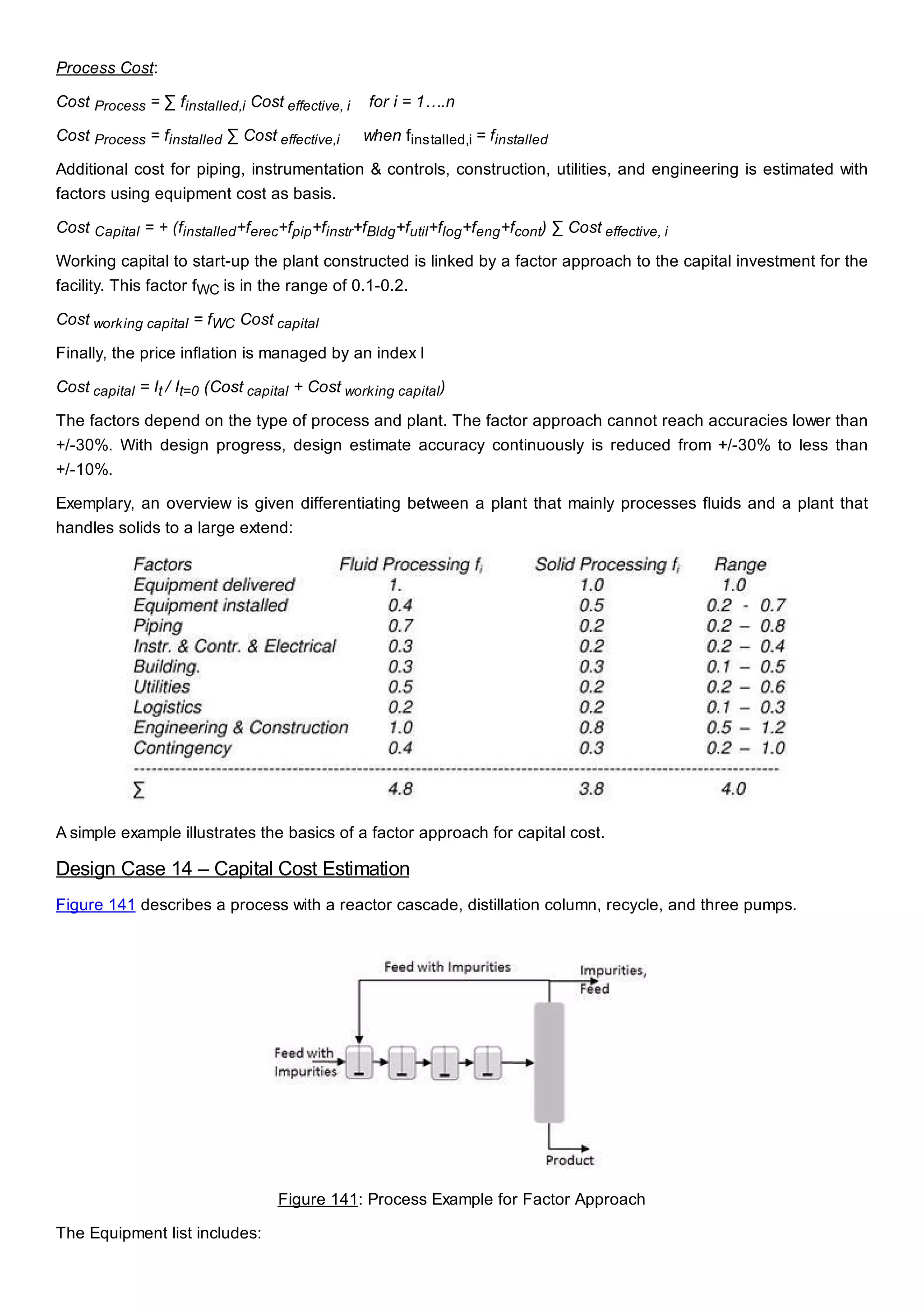

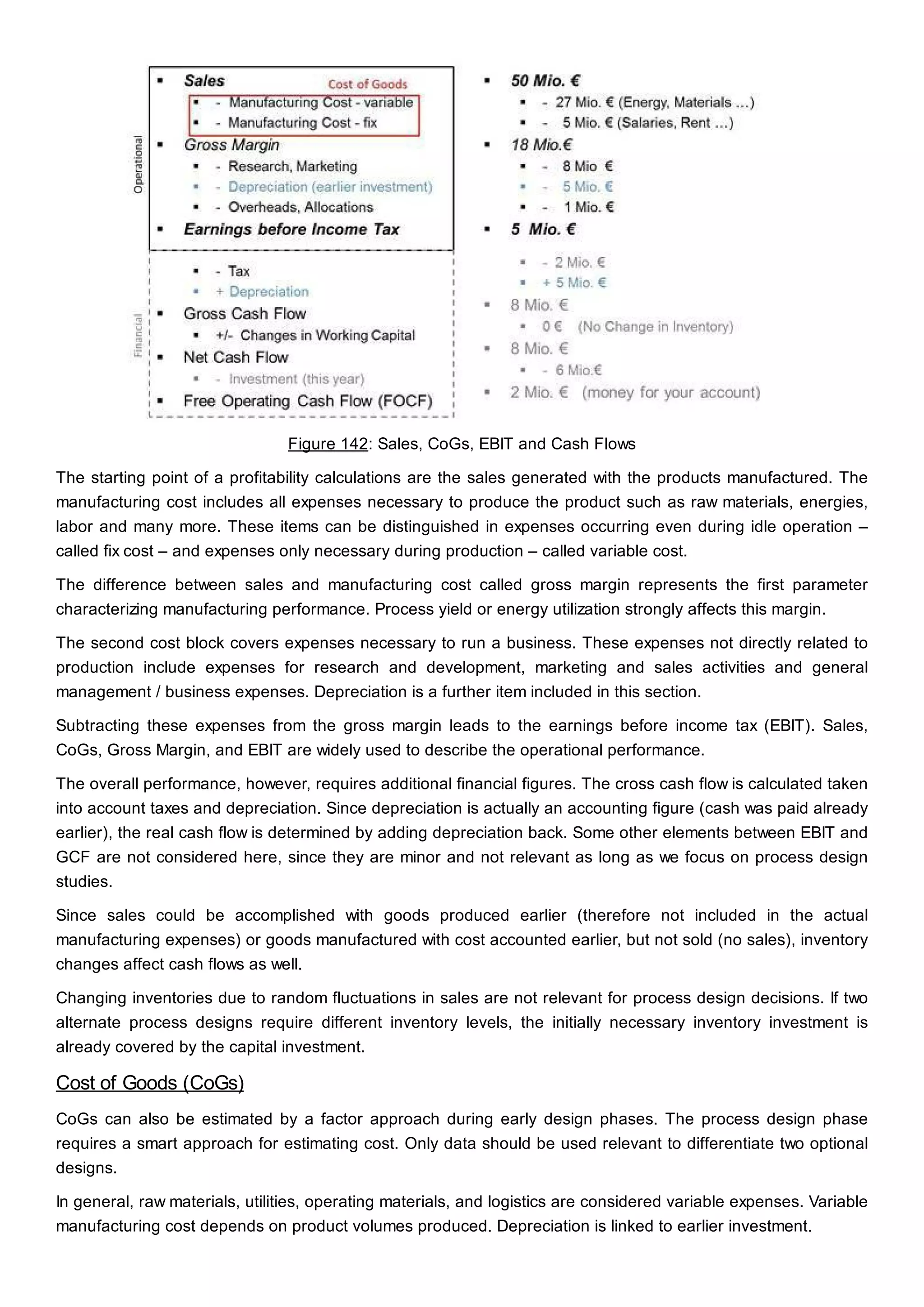

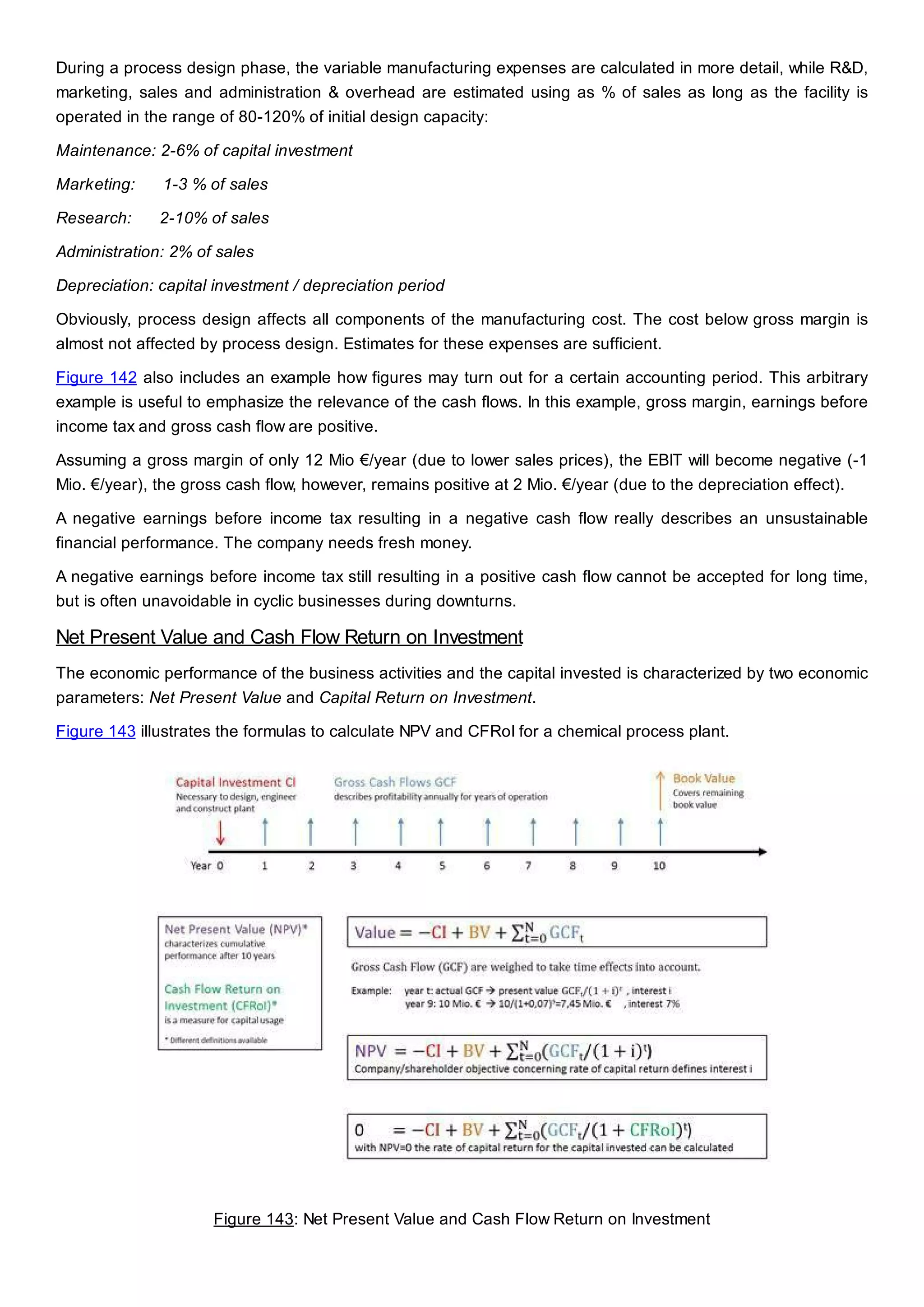

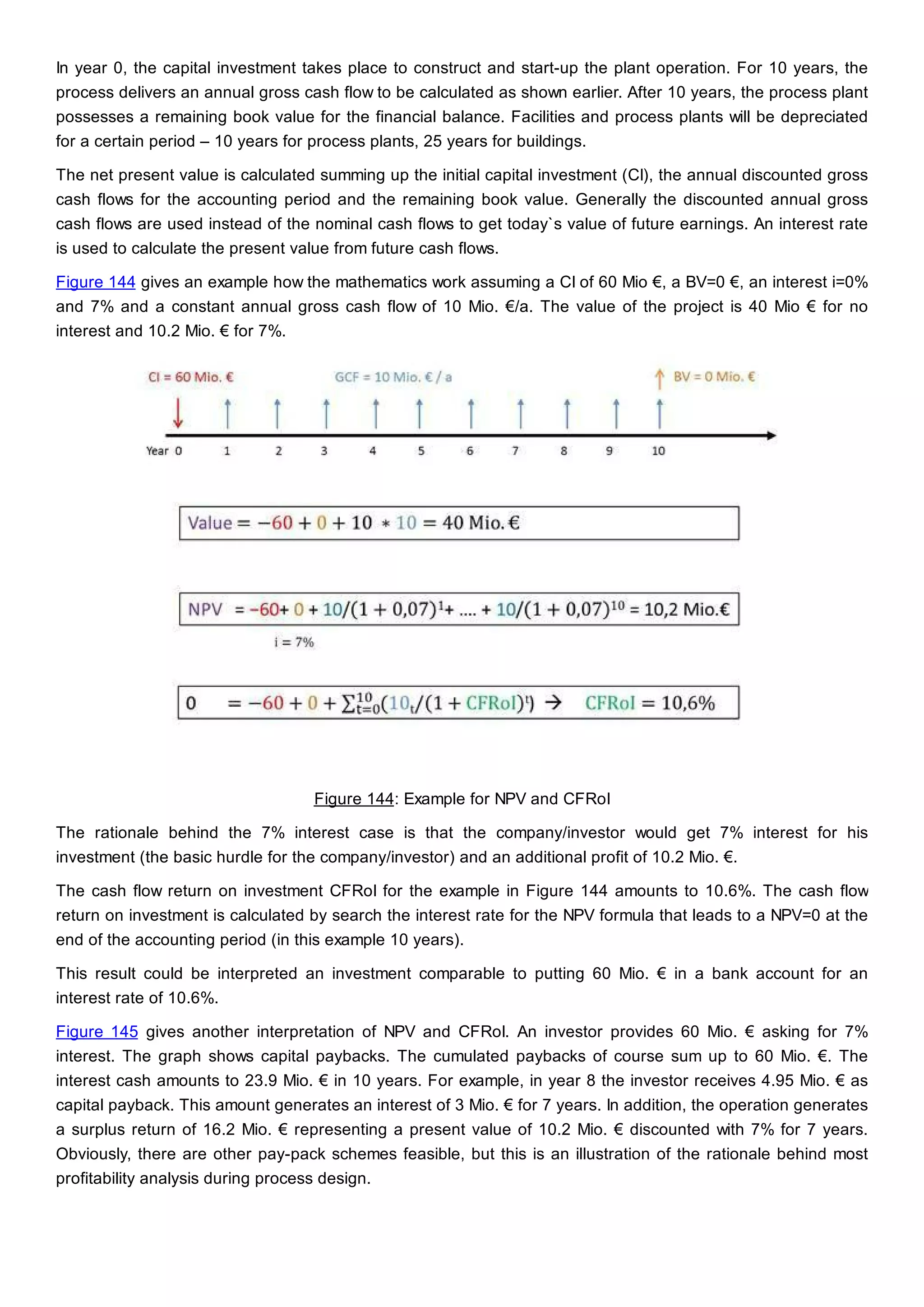

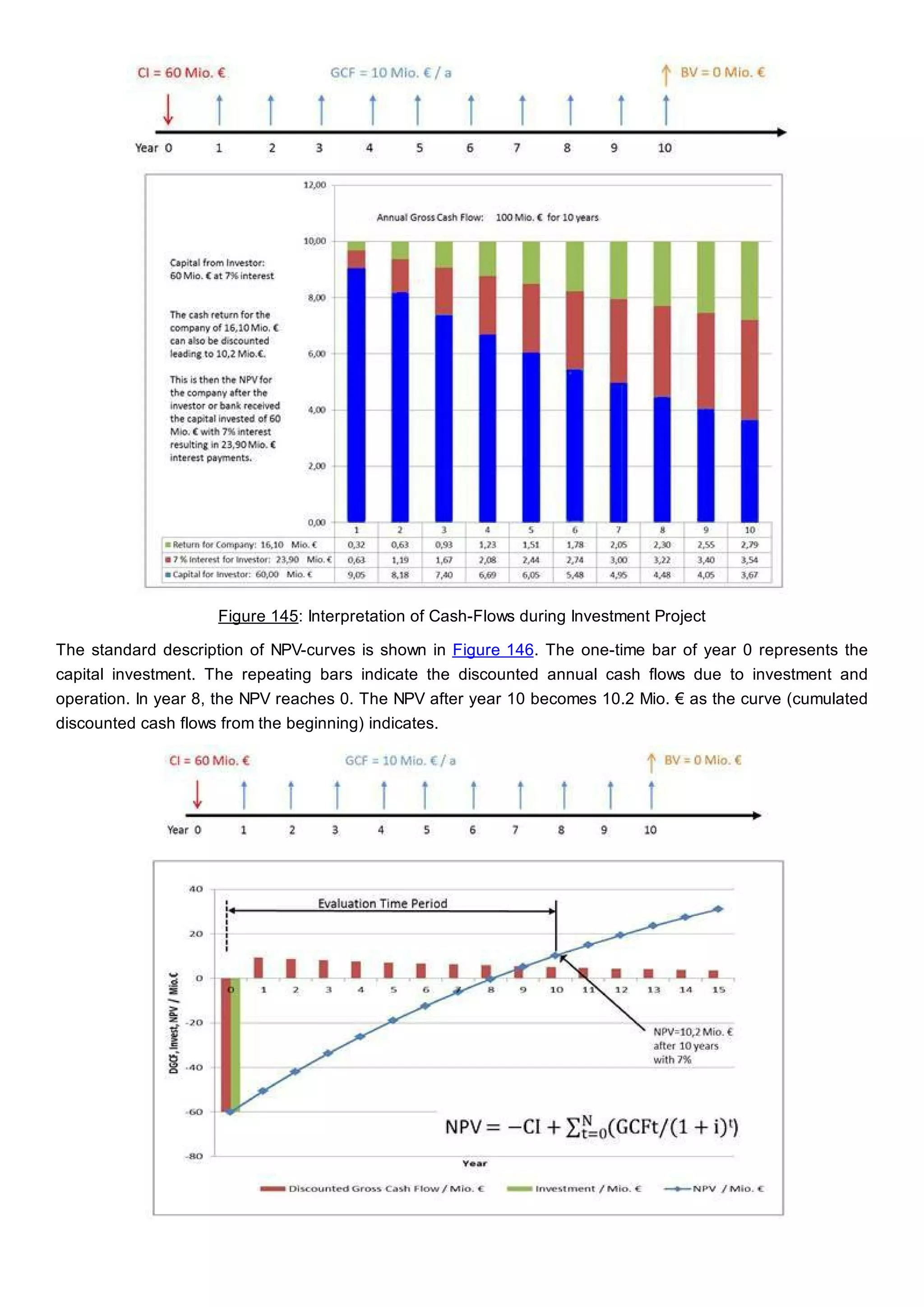

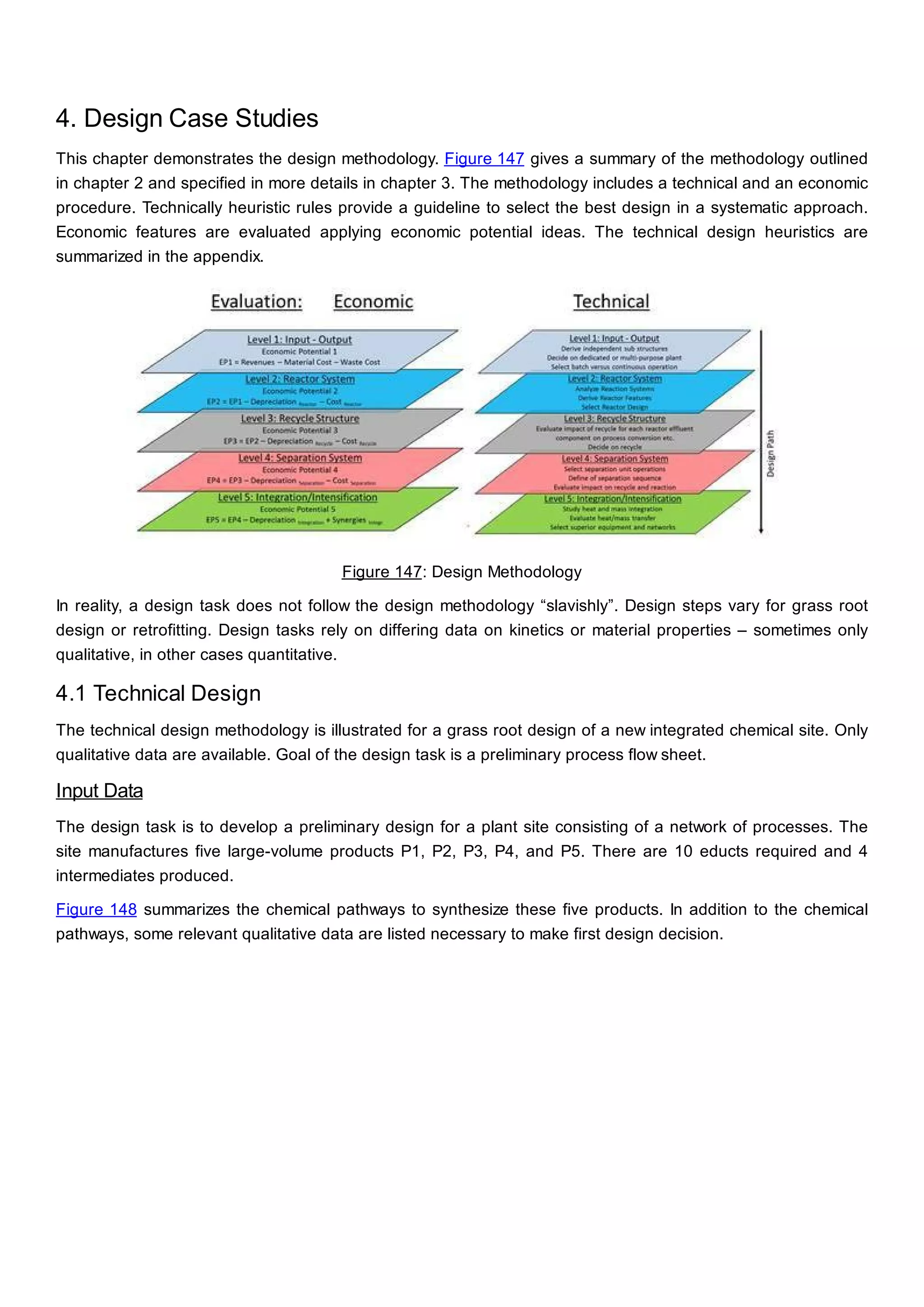

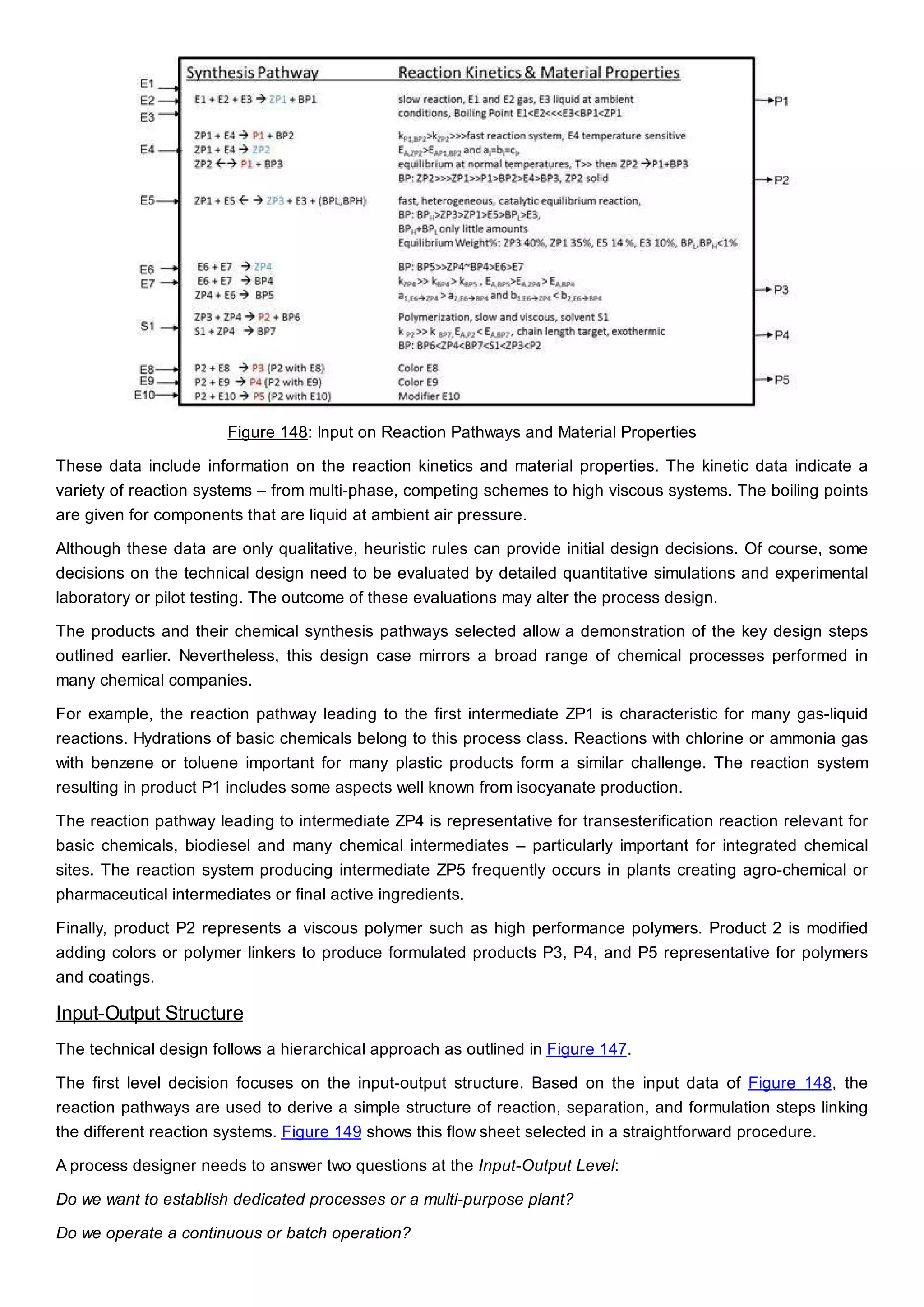

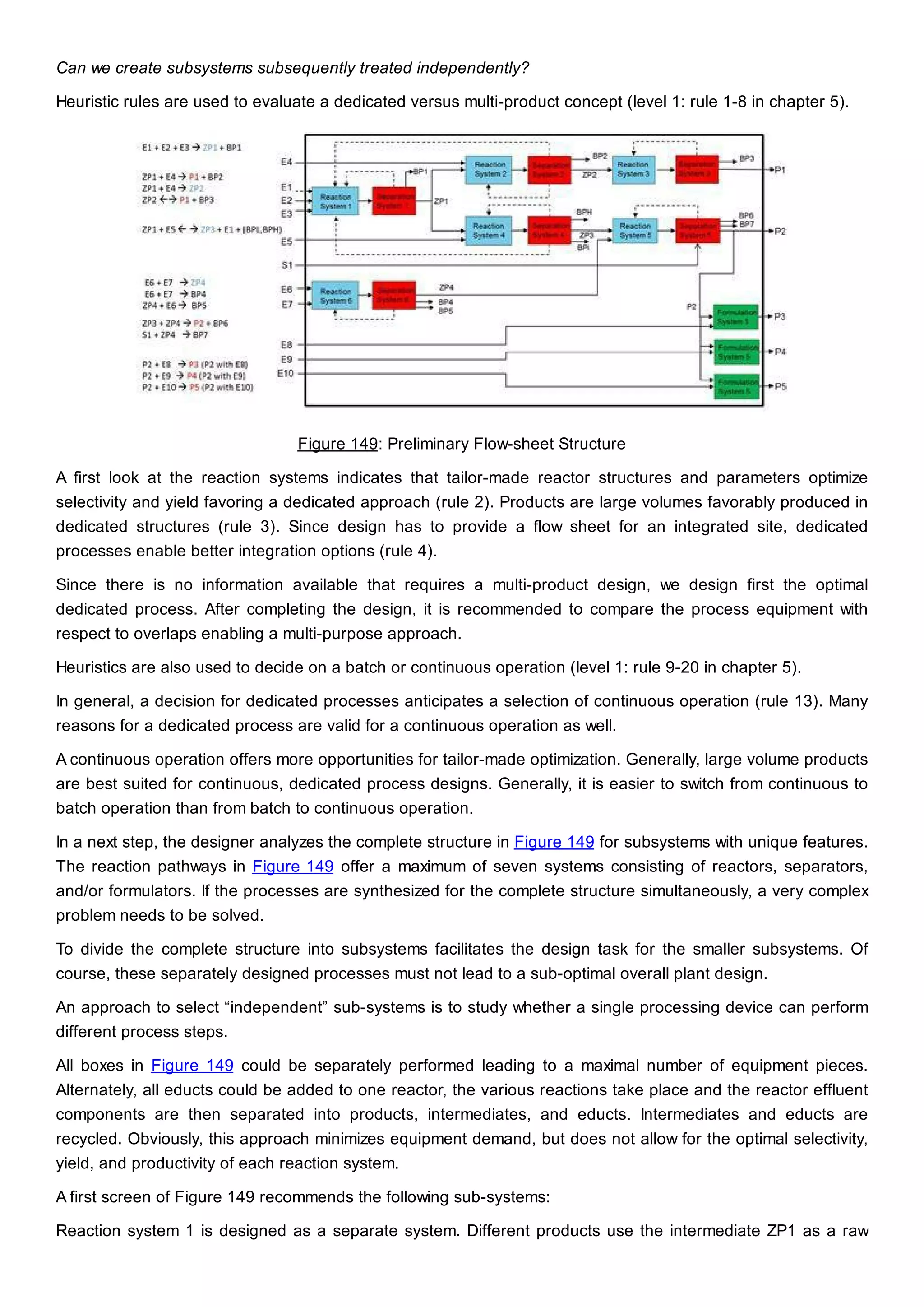

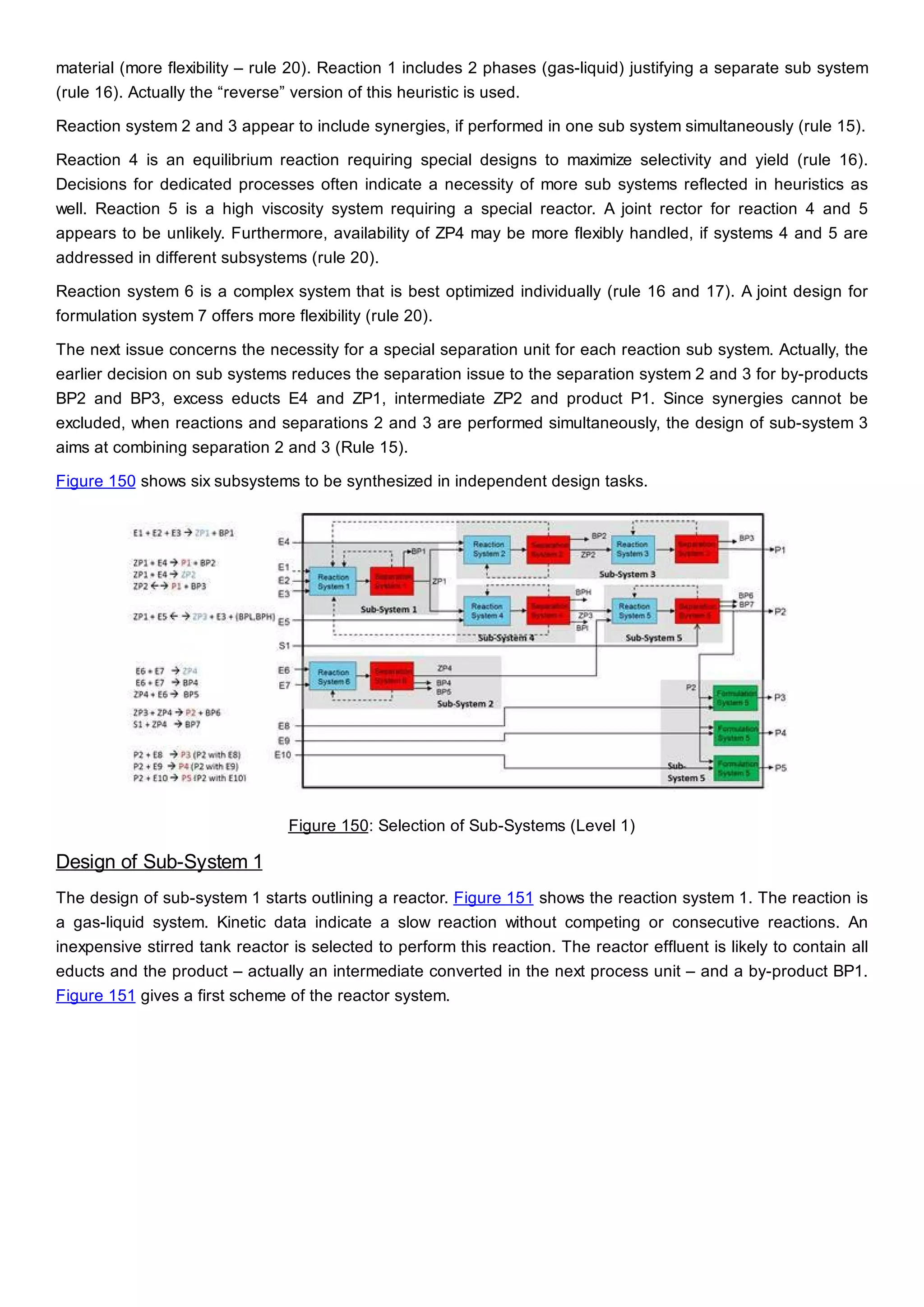

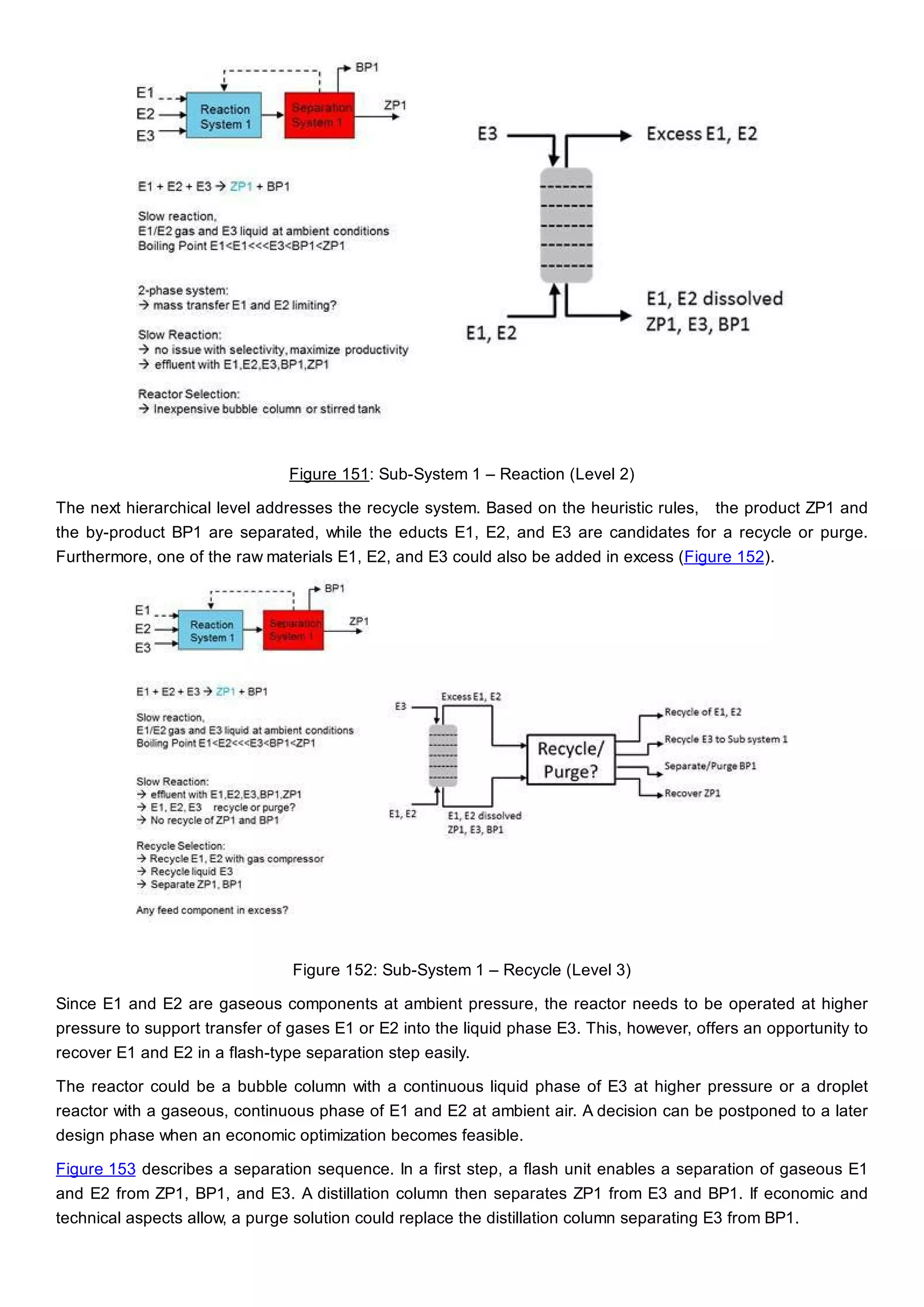

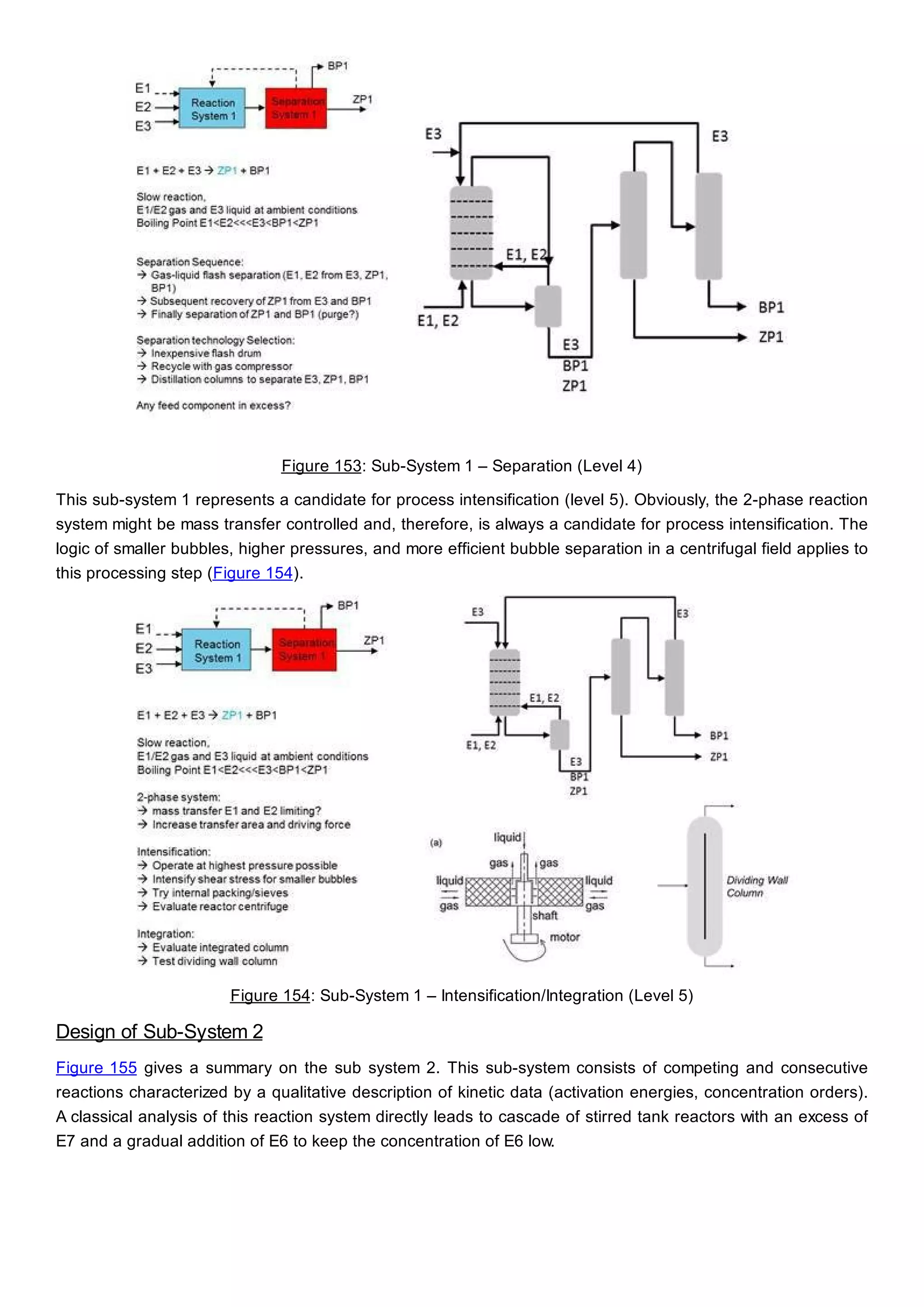

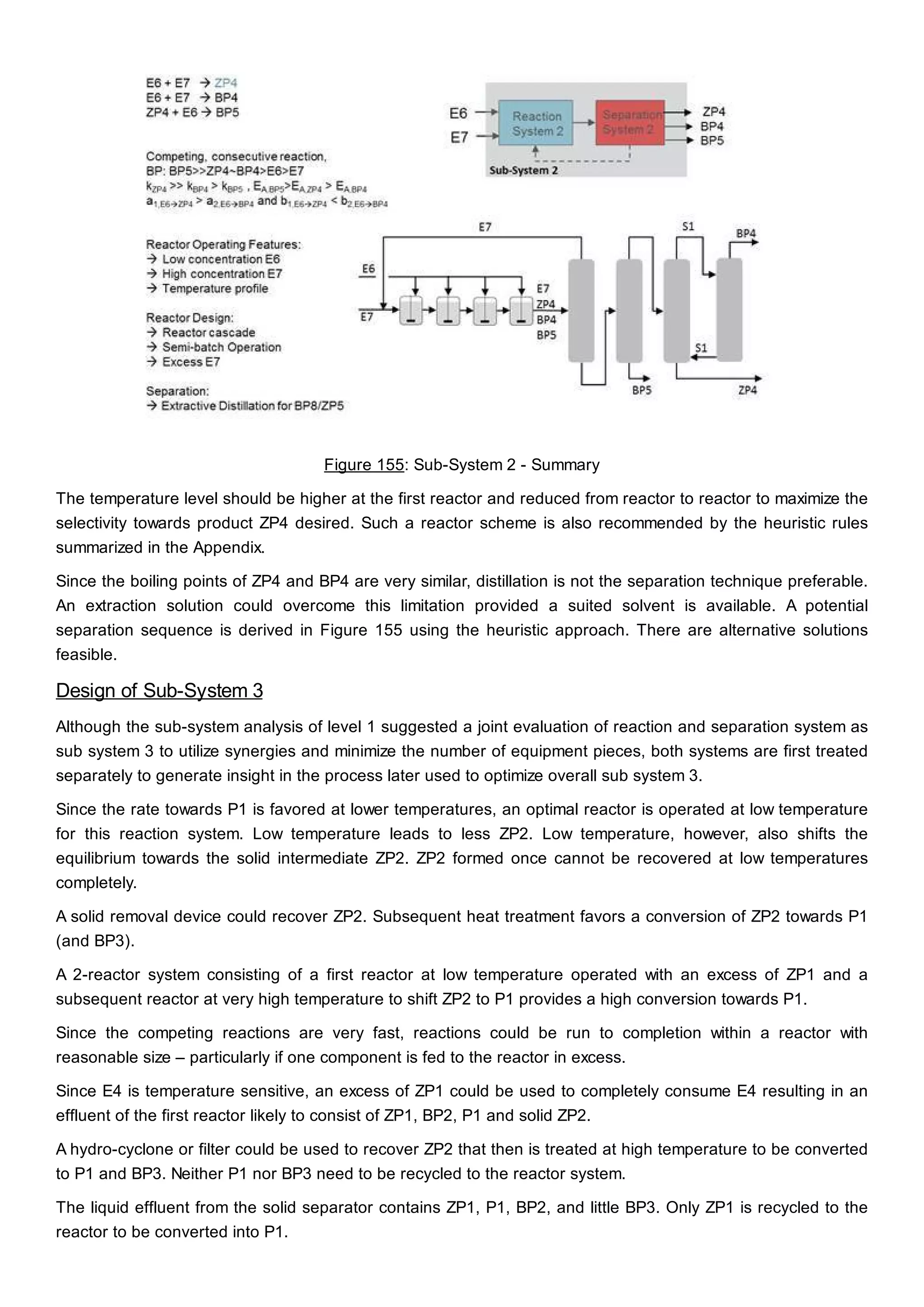

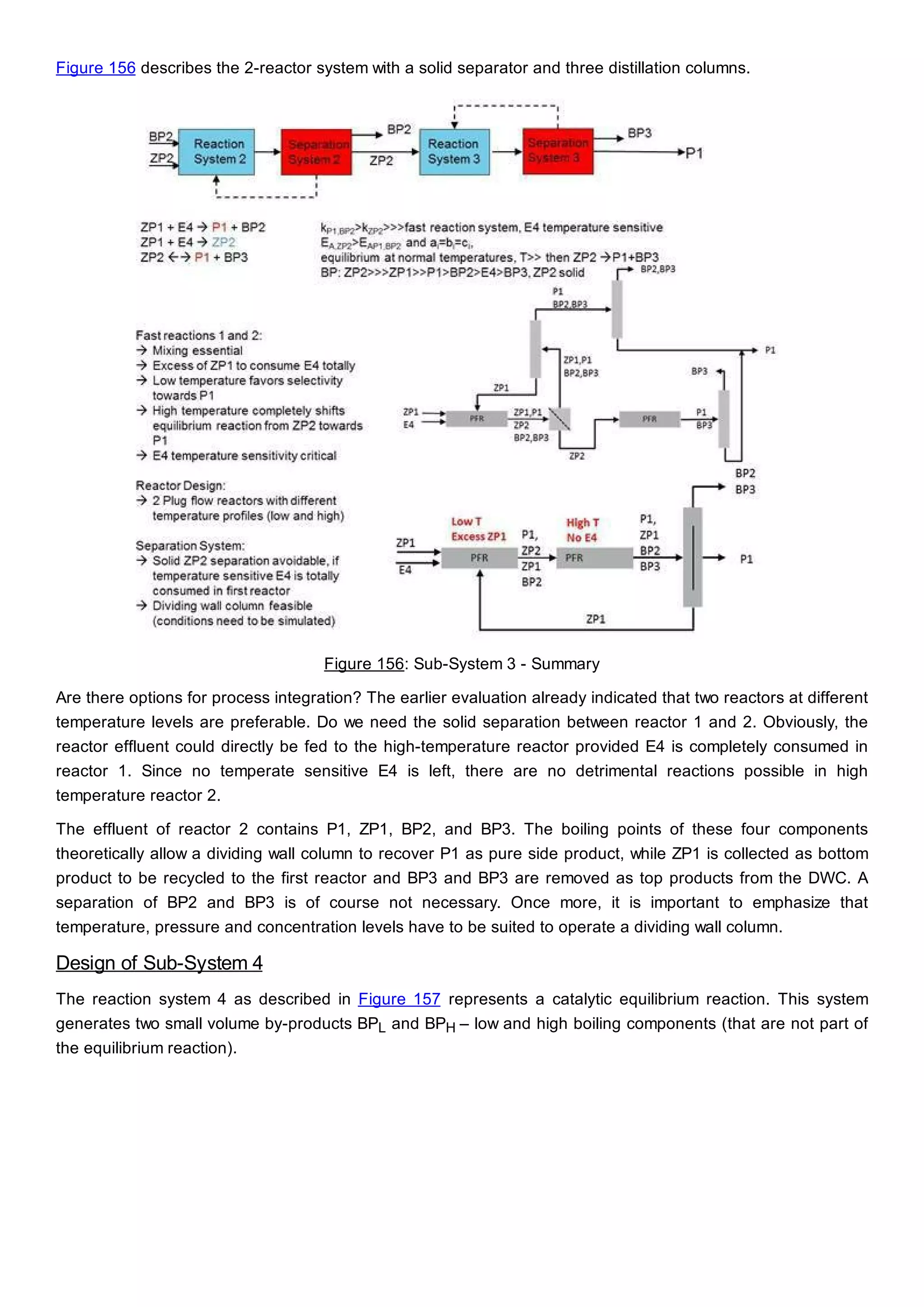

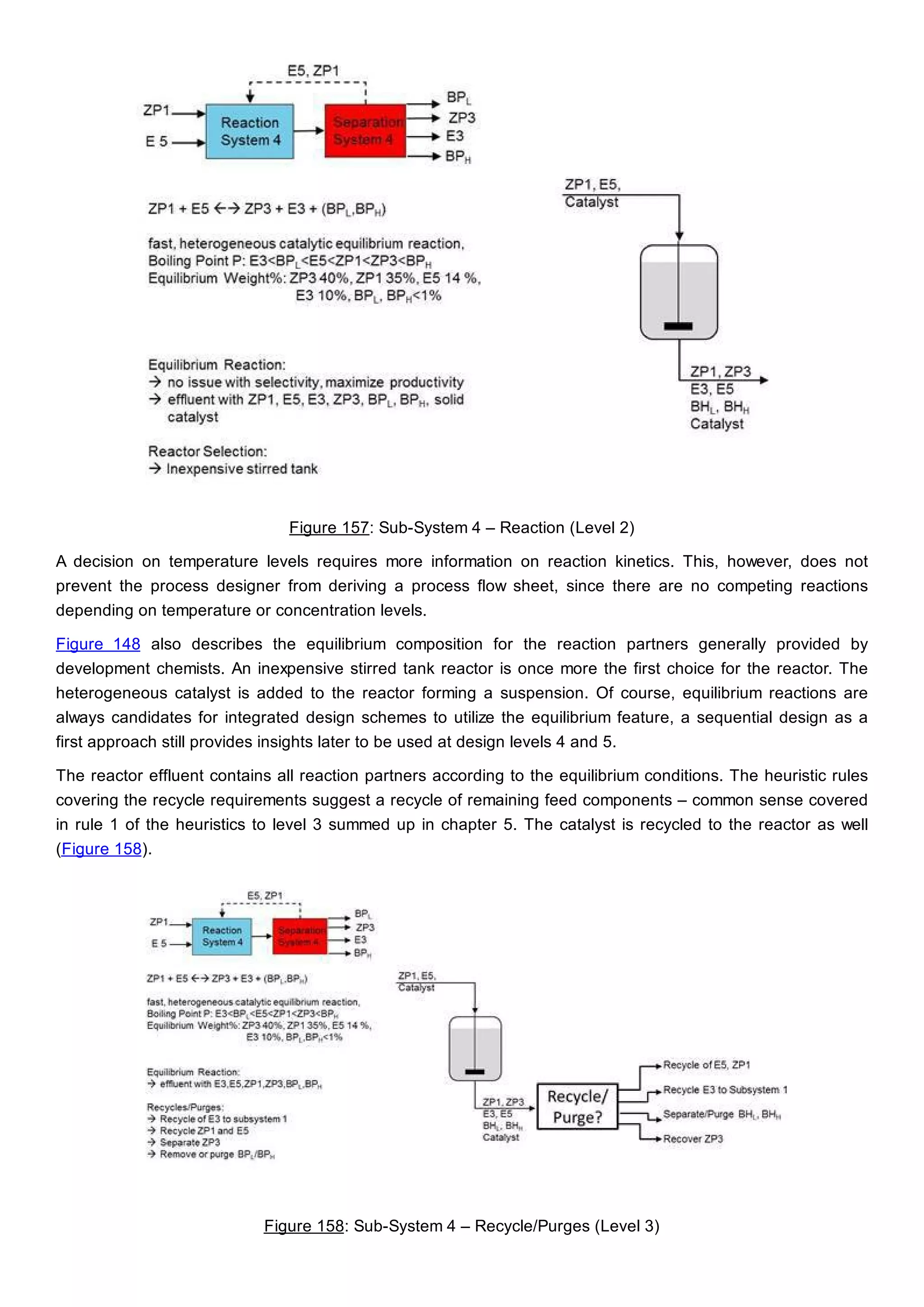

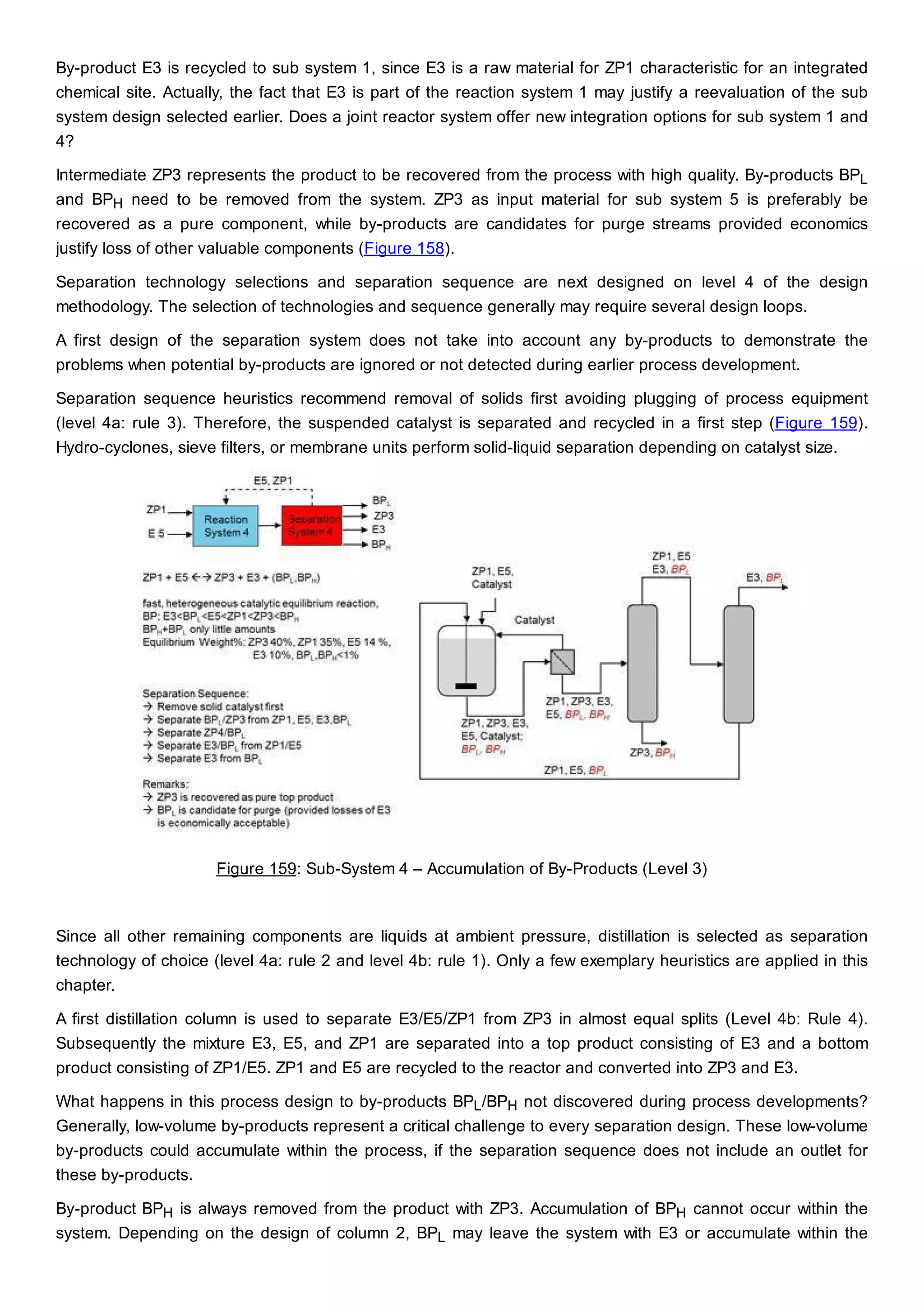

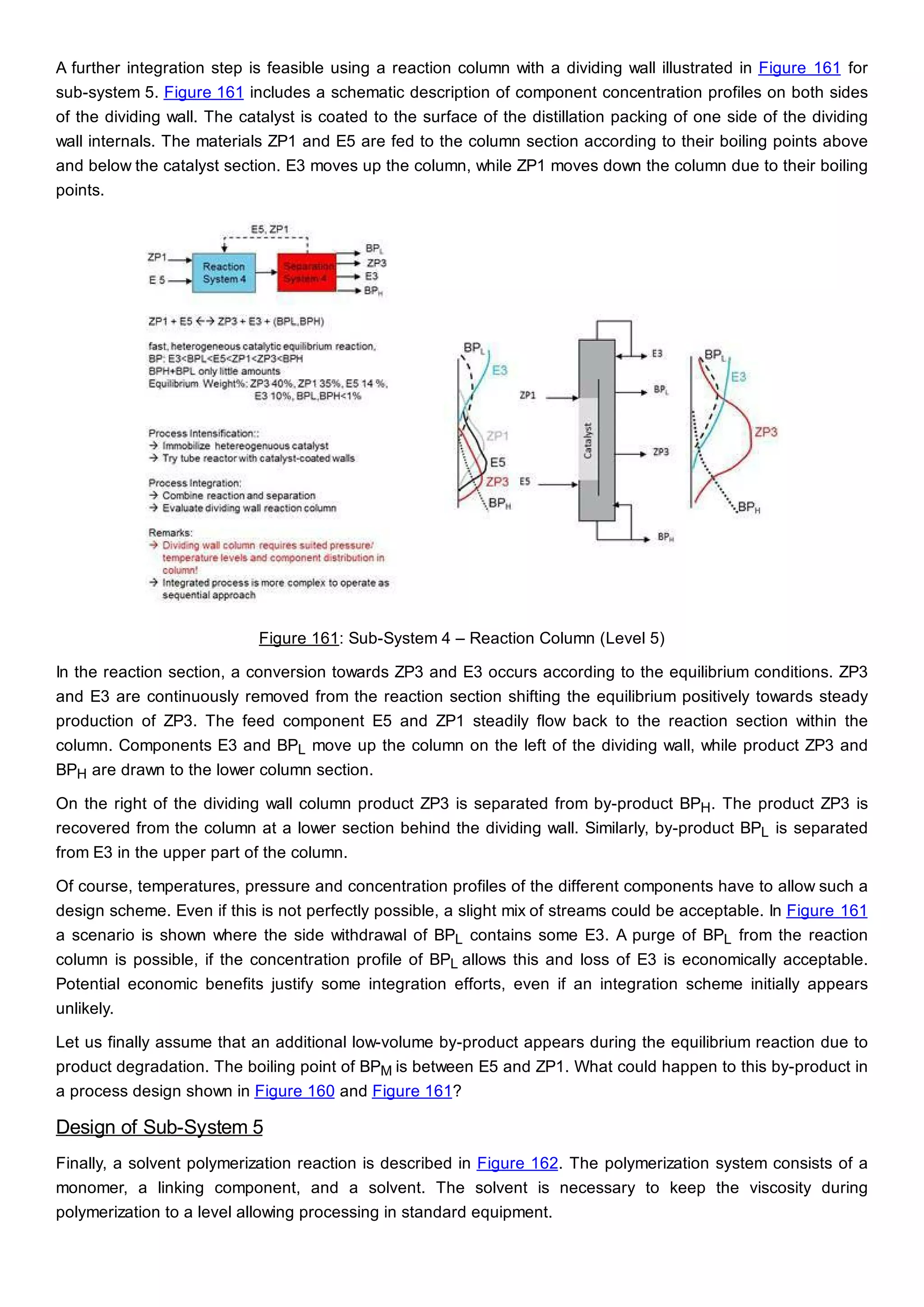

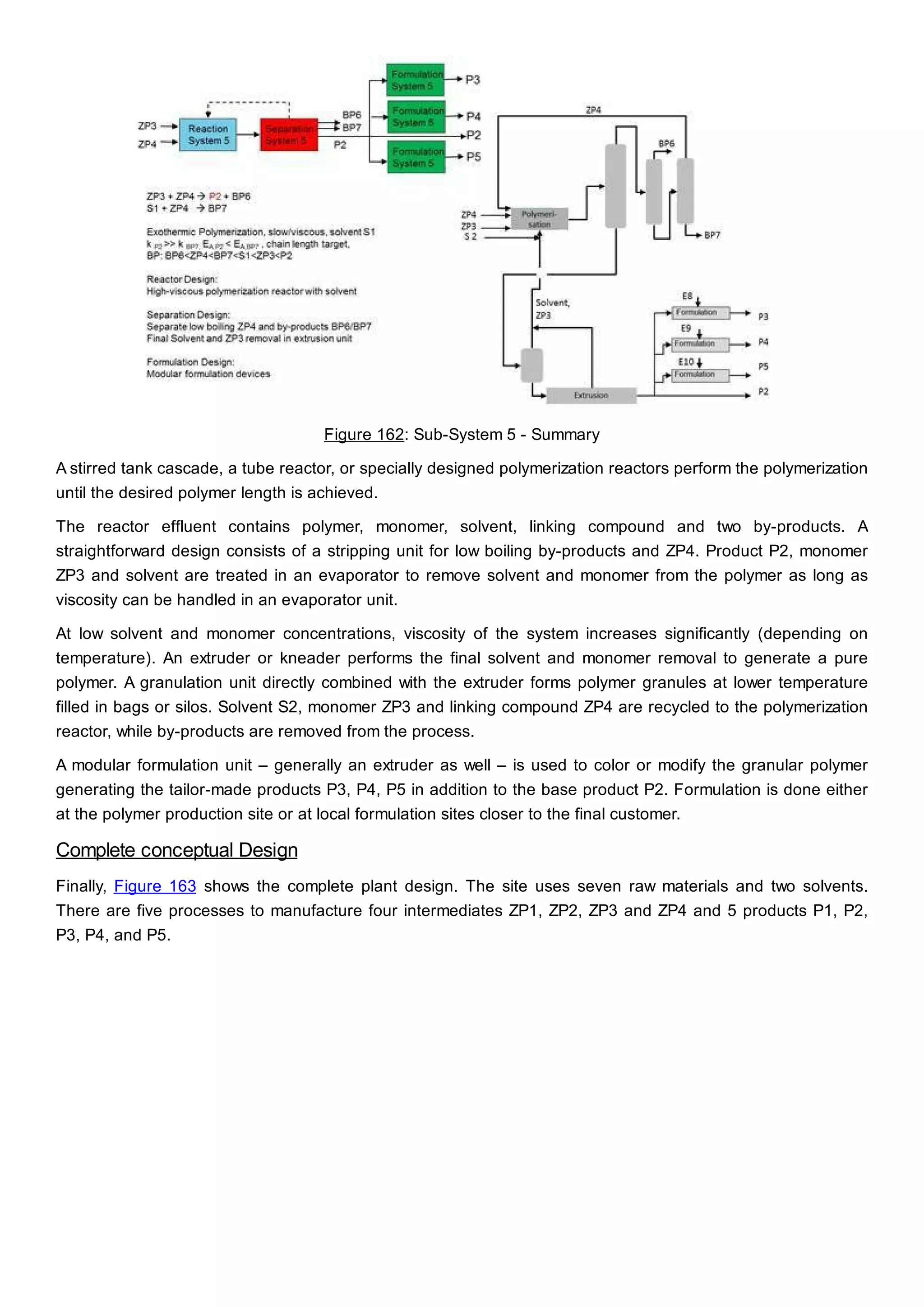

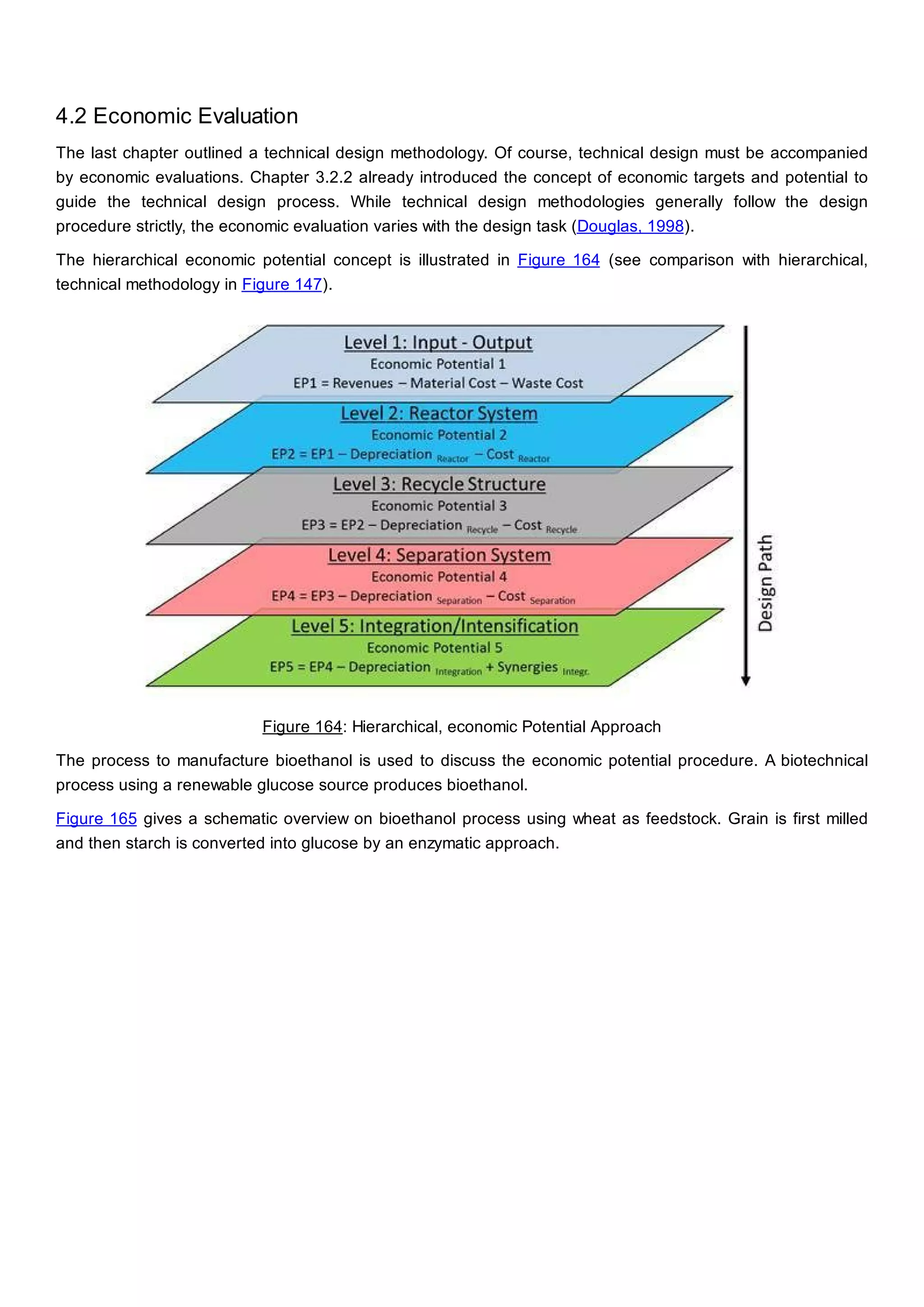

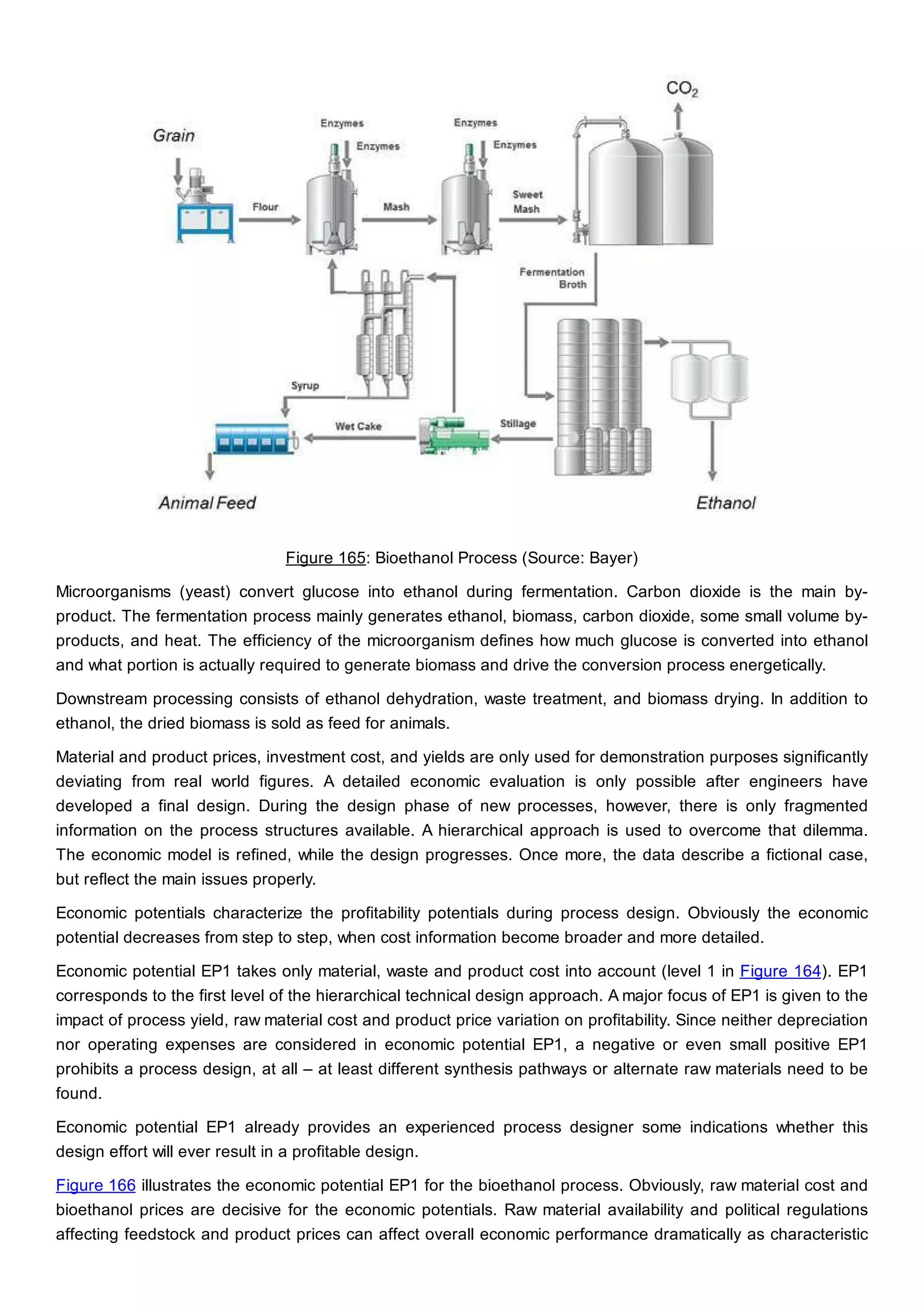

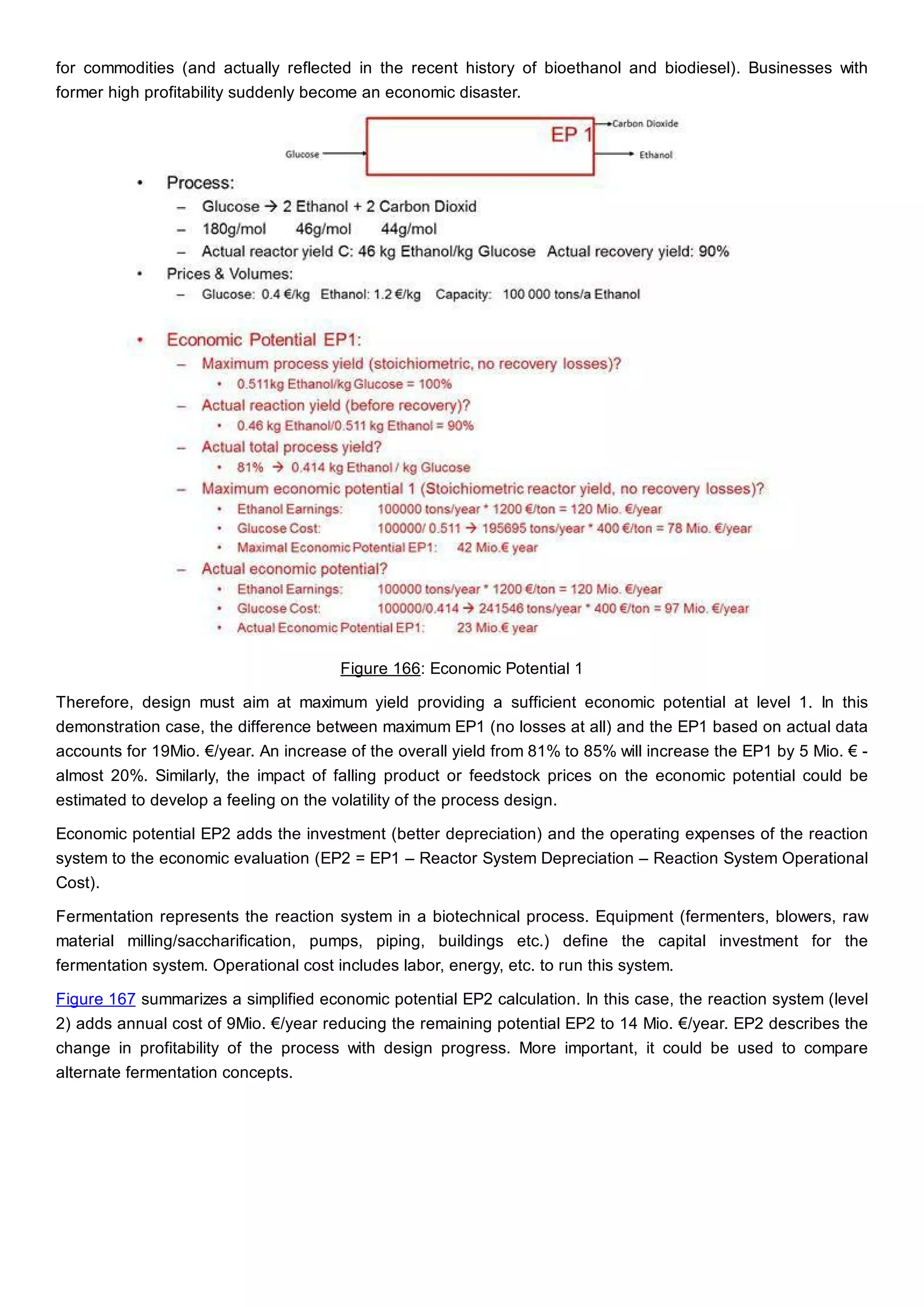

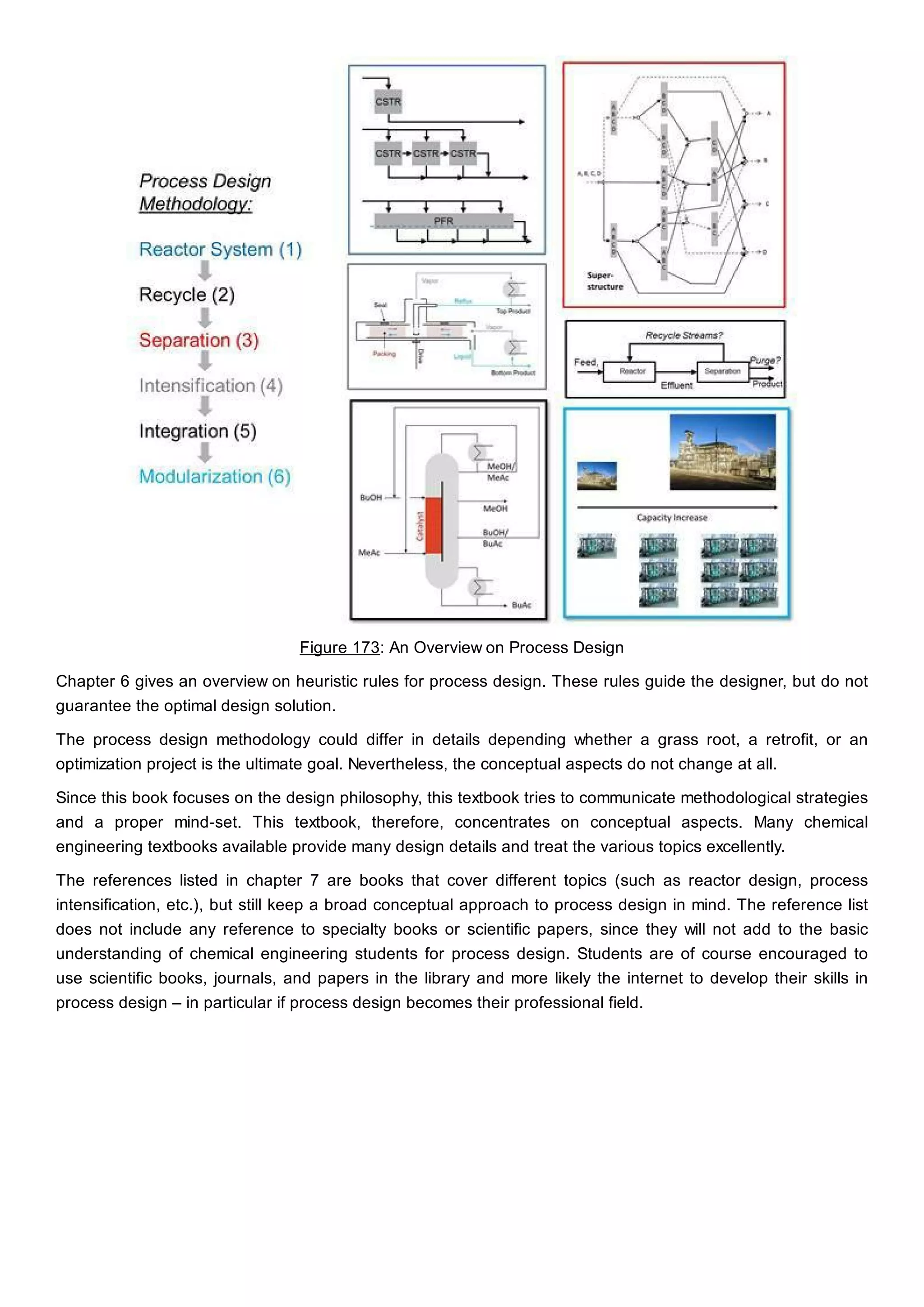

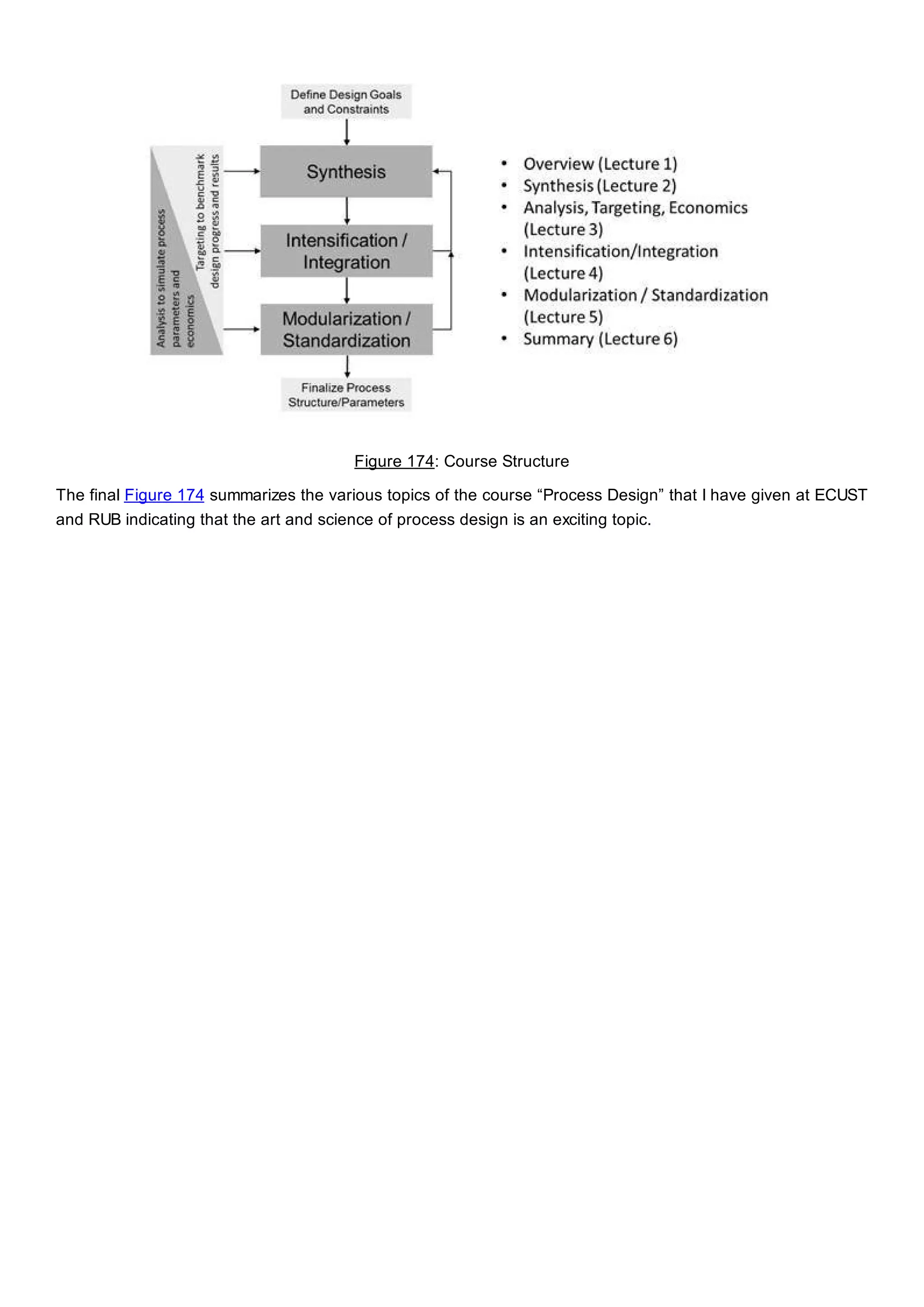

This document discusses process design methodology for chemical processes. It introduces concepts of complexity and uncertainty in process design due to changing business environments. A holistic process design methodology is needed to efficiently handle uncertainty and complexity. The goal of process design is to create a blueprint that converts raw materials to products. Process design defines the process structure and parameters based on input of product quantity and quality goals. The document outlines the overall process from idea to plant, noting that process design plays a key role in selecting the best process technologies and structure to optimize profitability.