This summary provides an overview of the March 2015 issue of PM Network magazine:

1) The issue features articles on topics such as nuclear reactor projects making a comeback after Fukushima, using virtual reality for journalism projects, and using project management approaches for startups and non-profits.

2) It also includes columns on cementing concrete connections in your career, facing fears as a project manager, and dealing with imposed deadline syndrome.

3) The issue provides information for project managers on earning a doctorate in project management, preparing for the PMP exam, and the evolution of project management as a mature discipline.

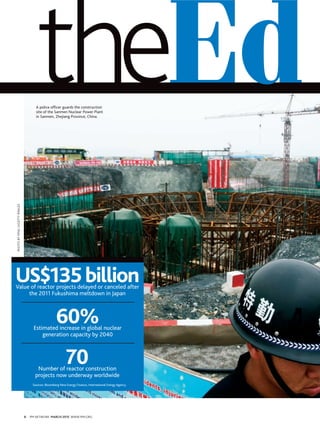

![8 PM NETWORK MARCH 2015 WWW.PMI.ORG

A Better Breed

The new wave of reactors

looks to improve upon

the old, especially when it

comes to safety.

In 2013, the U.S.

Department of Energy

launched a five-year,

US$452 million program

to create first-of-their-

kind small modular

reactors. They’ll not only

be one-third the size of

current nuclear plants

but also will aim to be

cheaper, faster to build

and safer than conven-

tional reactors.

Last year, Russia and China announced their intention to pursue a joint project that will build

six nuclear reactors floating on barges, supplying power to remote villages and oil platforms.

Placed in deep ocean waters, floating nuclear plants should be safer because they’ll be less sus-

ceptible to tsunamis or earthquakes, and in a worst-case meltdown scenario, they would be

cooled by the surrounding waters, according to Jacopo Buongiorno, PhD, a professor at the Mas-

sachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

“The biggest selling point [of floating reactors] is the enhanced safety,” Dr. Buongiorno, who is

researching and designing waterborne nuclear plants, said in a statement.

In France, an international consortium is executing the estimated US$20 billion ITER project,

which will be the world’s largest nuclear fusion reactor. It won’t generate as much long-lasting radio-

active waste as typical nuclear fission plants, and will be incapable of a meltdown. Seven state spon-

sors—China, the European Union, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the United States—are contributing

to the project, with the understanding that each member will have access to the technology needed to

theEdge

A NEWWAY

TO MAKEART

3-D printing isn’t just for

businesses. To allow its

students with disabilities

to harness their creative

instincts, the Victoria Educa-

tion Centre (VEC) in Poole,

England partially sponsored

the €1.7 million SHIVA project.

(SHIVA stands for Sculpture for

Health-care: Interaction and

Virtual Art in 3D.) In 2010, VEC

began collaborating with the

National Centre for Computer

Animation at Bournemouth

University in England to find a

way for children with limited

mobility and dexterity to cre-

ate three-dimensional objects.

The result is a new high-tech

tool that links eye-tracking and

touch-screen technologies to a

3-D printer to make students’

designs tangible.

“Children with disabilities

find it very difficult to do art in a

conventional sense,” said Mark

Moseley, assistive technologist,

VEC, and the technical lead on

the project, in a video onThe

Telegraph website. “I thought

this would be a great oppor-

tunity to develop a piece of

software that would allow them

to have these artistic experi-

ences, but in a virtual sense,

using technology that can

compensate for whatever it is

that they’re not able to do.”

The eye-tracking technol-

ogy translates a student’s gaze

into on-screen selections that

build an object from differ-

ent shapes. Users with visual

impairments can customize

display colors and sizes. User

preferences can be saved for

future use. —Brittany Nims

The Future of Nuclear

By 2030, these countries will build the most new nuclear reactors worldwide.

COUNTRY REACTORS UNDER CONSTRUCTION REACTORS PLANNED

China 26 60

Russia 10 31

India 6 22

South Korea 5 8

Japan 3 9

United States 5 5

World 70 179

Source: World Nuclear Association, 2014

The ITER fusion reactor project

site in April 2014, in Saint-Paul-

lès-Durance, France](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1e4baf98-8227-4c8a-bab9-8130db23fe48-161101131419/85/pmnetwork201503-dl-10-320.jpg)

![MARCH 2015 PM NETWORK 11

big,’” Ms. Nash says. “We had to focus more on proportion and measuring the way that

the virtual world looked.”

After incorporating the family’s feedback, the project team finalized its digital rep-

lica of the farm. The project allows users to virtually walk around the farm through

360-degree video segments, archival photos and text. “It has a museum-like quality

where you can go around and explore,” Ms. Nash says.

The project’s success also could be measured through its online presence: It resulted

in 430,000 page views. “That’s a very high number for us in engagement,” says Ms.

Nash, whose publication has a combined print and online readership of 420,000.

“I think we’ll be seeing more of these projects in newsrooms,” Ms. Nash says. “It’s

very exciting to see different ways to tell stories and what that might look like in the

future.” —Rebecca Little

China’s New

Stimulus Program

Housing has been both China’s boon and its bane. While the housing sector helped

the world’s second largest economy recover quickly from the global financial crisis, in

the past year it has helped drag down economic growth to its slowest pace since 2009.

“The linchpin of China’s economy is the housing market,” Alaistair Chan, an econo-

mist at Moody’s Analytics, told The Wall Street Journal.

The government’s recession-era stimulus measures helped the housing sector grow

mightily—and unsustainably. Due to an oversupply of overpriced houses, housing sales,

prices and construction have all dropped sharply. Cities such as Handan, where prop-

erty prices shot up 24 percent in the past four years, have become home to abandoned

real-estate projects. That’s having a major impact on the rest of the economy—20 per-

cent of which is tied to real estate.

The government is responding: The infrastructure and energy sectors are seeing a

surge in projects—and in the need for greater project management maturity.

A brief history of virtual-reality projects:

1957: Morton Heilig

invents the Sensora-

ma, a machine that

played 3-D images

and stereo sounds as

well as emitted smells.

1961: Philco Corp.

develops the Head-

sight, the first head-

mounted display—a

technology later used

in military training.

DEFENSE

GIANT

DIVERSIFIES

With U.S. defense spending in

decline, at least as a percentage of

GDP, the world’s largest defense

company is pursuing projects with

civilian applications in an effort to

shore up its future. More than 60

percent of Lockheed Martin Corp.’s

US$45 billion in 2013 sales came

through Pentagon contracts.

Several of Lockheed’s current

research projects, like the patented

Perforene membrane, could gener-

ate commercial interest around the

world. It’s a one-atom thick sheet of

graphene that can be used to desali-

nate seawater. The product could

interest Persian Gulf nations, who

might also order some of the orga-

nization’s weapons systems. More

surprisingly, Lockheed Martin has

partnered with Kampachi Farms LLC

and the Illinois Soybean Association

to develop fish farm pens that will

drift on open-ocean currents and be

tracked by satellites.

Lockheed Martin is also develop-

ing a compact nuclear fusion reactor

that might initially power naval

ships but could be expanded for

commercial use by cities. “Should

the [technology] develop, that can

result in a very large commercial

market,” Ray Johnson, Lockheed

Martin’s chief technology officer,

told TheWall Street Journal.

This isn’t the first time Lockheed

Martin has tried to diversify its

project portfolio to hedge against

military cuts. In the 1990s, the orga-

nization stepped into the telecom-

munications market by buying three

satellite operators. It sold them at

a steep loss in 2001. The company

says its focus on global issues like

energy, food and water this time

around will act as a safeguard.

—Brittany Nims

THE REALITY OF VIRTUAL

1991: Virtuality Group

adds virtual reality to

video arcade games.

1997: Georgia Tech

researchers use virtual

reality to design war-zone

scenarios for use as

therapy for veterans.

2014: Facebook acquires

Oculus VR, the company

that makes the Rift, for

US$2 billion.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1e4baf98-8227-4c8a-bab9-8130db23fe48-161101131419/85/pmnetwork201503-dl-13-320.jpg)

![MARCH 2015 PM NETWORK 19

“[Project management

standards] ensure that

we’re following all

the different systems

engineering processes to

determine what looks

promising to continue to

mature and test.”

Small Talk

Best professional

advice you’ve ever

received?

Maintain your bal-

ance. You need to be

balanced in life, be-

cause work can really

consume your time.

The one skill every

project manager

should have?

The ability to build a

team with a shared

vision.

Favorite thing to do

in your spare time?

Running. I try hard to

stay at 40 miles [64

kilometers] a week.

My kids both run

cross-country, so I run

with them.

urgency to increase homeland defense—that’s the

origin of the Sea-Based X-band radar. It can see a

baseball from 2,500 miles [4,023 kilometers] away.

The third radar system is the AN/TPY-2 [the

Army Navy/Transportable Radar Surveillance]

radar. We’re contracted to build 12 of those. Ten

have been delivered, and two are still in production.

What do these radars do?

They search airspace to find and track ballistic mis-

siles. But the other important thing they do—and

the thing that X-bands are particularly well suited

for—is discrimination. When there’s a launch of

a missile, lots of things end up in flight with it.

The job of the Missile Defense Agency is to find

and intercept the lethal warhead. But you’ll have

the tank, the boosters and debris, and there can

be intentional countermeasures as well. This can

make it really hard to find and intercept the lethal

object with our missiles to protect our homeland

and our assets in theater. Intercepting something

traveling in space hundreds to thousands of miles

away is very challenging.

What projects does your office execute to

overcome that challenge?

Every year or two there’s a new software build

related to discrimination in particular. One of the

roles I have is overseeing development of a long-

range discrimination radar, which is going to start

this year—a new Alaska-based radar for discrimi-

nation. We’re developing the requirements and

capabilities of that system. We also have other TPY

radars in production.

So there’s a big focus on increasing our ability to

distinguish the lethal object.

Why has discrimination become a more

urgent concern?

Threats continue to grow in number and capabil-

ity. Whereas in the past we were dealing with

relatively simple threats, at least from the smaller

rogue states, those countries’ capabilities have

continued to increase. If we look out another five

to 10 years—and it takes us that long to develop

new capabilities, too—it looks like they’re going

to have the capability to add countermeasures to

make it harder for us to determine what the lethal

object is.

How does your office use project

management standards when developing

software capabilities?

Project management standards help ensure program

success, and they do that by giving us best practices

and a structure that helps ensure rigor. They ensure

that we’re following all the different systems engi-

neering processes to determine what looks promis-

ing to continue to mature and test, and to ensure it

has independent verification. The Missile Defense

Agency has a robust test program to make sure

these things really work before we field them.

What does the testing phase look like?

We build a little, test a little. We’re building incredi-

bly complex, challenging capabilities. Intercontinen-

tal ballistic missile intercepts approach 10,000 miles

[16,093 kilometers] per hour—exo-atmospheric,

so way up in space. We have very small margins

of error. So we build a bit of capability, test it and

make sure we don’t get unintended consequences—

that’s been a big risk—before we keep building and

continue to add the next capabilities.

It takes longer, but because we’re shooting down

missiles and launching missiles, we don’t want

anything to go wrong. So it is very much a con-

tinual build process.

How has the U.S. budget “sequestration”

of 2013, which lowered defense spending,

affected your office?

It’s made for a challenging environment, espe-

cially given uncertainty around future funding.

But so far we’ve mitigated that. Some things have

been delayed a bit, but discrimination has been

a very high priority and that’s actually received

additional funding. PM](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1e4baf98-8227-4c8a-bab9-8130db23fe48-161101131419/85/pmnetwork201503-dl-21-320.jpg)

![20 PM NETWORK MARCH 2015 WWW.PMI.ORG

VOICES ProjectToolkit

From looming deadlines to scope

changes to overbearing clients, projects

can be stressful. But the stress

doesn’t have to be overwhelming.

We asked practitioners:

When the pressure is on,

how do you relieve your

team’s stress?

Under

Pressure

Sweat It Out

Trying to deliver excellent quality under

tight deadlines carries a strong risk of

stress which, in my experience, reduces

team members’ productivity and efficiency.

We’ve adopted a practice that may seem less im-

portant than, say, risk management, but is actually just

as useful: 20 minutes of daily exercise. A professional

trainer visits the office and leads us through stretches,

relaxation and strengthening exercises, along with

games that reinforce the team dynamic. The sessions

aren’t mandatory, but most team members partici-

pate. Not only does exercising prevent strain injuries

(like the ones you might get from sitting in front of the

computer for several hours and having bad posture),

but the sessions improve the team’s mental health and

contribute to better performance and productivity.”

—Andrea Paparello, PMP, project manager, LDS-LABS,

Fortaleza, Brazil

Take a Laugh Break

I’ve found the best way to handle stress is

humor and team camaraderie, especially

when we’re trying to problem-solve. I

encourage the team to brainstorm together by asking

them to share a relevant experience (“tell us about the

last time you dealt with a similar issue”) and the lessons

learned from it. Then I’ll attempt to find some humor in

the event. But humor doesn’t have to be about work—it

can be a silly chat for a few minutes about what hap-

pened at lunch. If all else fails, I’ll share a Dilbert comic

strip [known for its satirical office humor].

Once, on a very challenging project with an extremely

tight deadline, our developers were having trouble com-

ing up with a solution to a problem at a meeting. So they

took a break to banter. Even though they were joking, I

could tell it was a productive conversation, so I didn’t stop

the flow of energy. We all laughed for a few minutes and

gave our brains a break from the stress. By the time the

meeting ended, the team had come up with a solution.”

—RaeLynn DeParsqual, PMP, project manager, Insight

Global, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA

Inclusive Planning,

Constant Communication

Avoiding surprises—both from team

members and issues that may arise with

the project itself—is a good way to

keep team stress to a minimum.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1e4baf98-8227-4c8a-bab9-8130db23fe48-161101131419/85/pmnetwork201503-dl-22-320.jpg)

![34 PM NETWORK MARCH 2015 WWW.PMI.ORG

Lavasa aims to take advantage of its proximity to

Pune, a booming software hub 40 miles (64 kilome-

ters) away. Konza Techno City, Kenya, a US$14.5

billion development, will be 37 miles (60 kilometers)

from the capital of Nairobi.

China has offered a counterpoint lesson. As many

cities have sprung up in remote areas, the country

has seen an epidemic of ghost towns—newly con-

structed urban centers that did not attract busi-

nesses and residents and now sit largely empty.

“These Chinese cities were built mainly as specula-

tive housing projects, not necessarily corresponding

to where people want to live,” Dr. Ben-Joseph says.

It may seem counterintuitive to build a new city

near another, more established one, but such urban

clusters carry distinct advantages. “You can ben-

efit from and complement the social and economic

dynamics of the metropolis. This makes the new city

much more attractive for companies and the types

of tenants they envision hosting,” says Luis Carvalho,

PhD, senior researcher, European Institute for Com-

parative Urban Research, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

To help future residents and businesses appreciate

the allure of their city over others, project sponsors

must coordinate with nearby cities to make sure

they’re complementing others’ appeal, not duplicat-

ing it. “Many new cities are designed to provide heavy

incentives to lure companies, but those are often

insufficient to match the social advantages of other

places, let alone the fact that they can hardly be kept

over time,” Dr. Carvalho says. “This would call for the

integration and coordination between the new city

and other nearby locations, to avoid negative-sum

competition for companies and tenants.”

Source: United Nations

“[New] Chinese cities

were built mainly as

speculative housing

projects, not necessarily

corresponding to where

people want to live.”

—Eran Ben-Joseph

The Urban FutureThe world will see not only more cities, but bigger ones too.

City Dwellers

Percentages and populations of

the world living in urban areas

Big

Medium-sized cities, each with 1 million

to 5 million inhabitants

1950

100%

10%

50%

2014 2050

30% 54% 66%

746

million

people

3.9

billion

people

6.4

billion

people

417827 million people

43300 million people

8 percent of the global

urban population

2816 in Asia, 4 in Latin America,

3 in Africa, 3 in Europe,

2 in North America

453 million people

12 percent of the global

urban population

63400 million people

9 percent of the global

urban population

41Top two:

Tokyo, Japan, 37 million;

Delhi, India, 36 million

5581.1 billion people

Bigger

Large cities, each with 5 million to 10

million inhabitants

Biggest

Megacities, each with more

than 10 million inhabitants

2014 2030

2014 2030

2014 2030

medium-

sized cities

large cities large cities

medium-

sized cities

Top two: Tokyo, Japan, 38 million;

Delhi, India, 25 million

megacities megacities](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1e4baf98-8227-4c8a-bab9-8130db23fe48-161101131419/85/pmnetwork201503-dl-36-320.jpg)

![40 PM NETWORK MARCH 2015 WWW.PMI.ORG

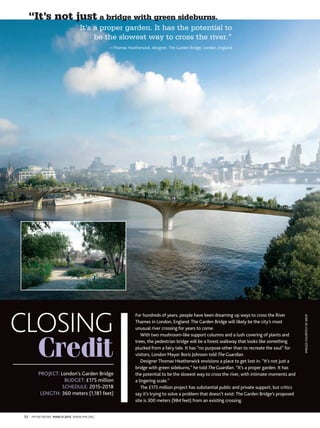

Way says. Again, the team had to combine the cli-

ent’s general goal with its own expertise as well as

its research on other new Chinese hospitals. In the

end, the team successfully planned and designed a

modern, 2,000-bed facility.

GIVE AND TAKE

The government of Guangzhou, the

third biggest city in China, has under-

taken a US$7.5 billion effort to revital-

ize large swaths of the city, dubbed the

north axis and south axis.

“Our objective was to create a sustain-

able and livable area for about 500,000

people in Guangzhou, without creating

a negative impact on the surroundings,”

says David Masenten, senior associate,

Heller Manus Architects, the San Fran-

cisco, California, USA-based firm that

won the redesign bids.

In 2009, the team began the first

phase: the north axis. “This comprehen-

sive urban core master plan of 2.4 square

miles [6.2 square kilometers] redesigned

the central business district,” Mr. Masenten says.

The project comprises commercial and residential

buildings, a sports facility, a railway and bus trans-

portation hub and extensive open spaces. With

a completion date of 2025, the south axis has

fewer original features than its counterpart but

more space: 15.5 square miles (40.1 square kilo-

meters) of the southern city center.

Dealing with existing city structures pre-

sented both opportunities and challenges. “By

choosing not to demol-

ish buildings of suf-

ficient quality, we were

taking a very sustainable

approach of saving the

energy that would be

lost in demolishing and

recycling materials,” Mr.

Masenten says. “How-

ever, most of the existing

buildings on site were not

built to any larger master

plan, thus creating a con-

flict with planning goals

and design.”

He credits precise planning for the

mitigation of potential risks. “We care-

fully phased the plan to leave some exist-

ing buildings for the short term, while

slating them for eventual removal,” Mr.

Masenten says. “This gives the city time

to re-evaluate the structure and the loca-

tion in the future when the quality and

needs of the building may change.”

While typical Chinese grid systems

cater to cars, not to pedestrians, Mr.

Masenten says, this project had sustain-

able mobility as one of its core objec-

tives—so Heller Manus had to convince

local stakeholders to think differently. “By

using examples of walkable cities, we were

able to convince local planners to adopt a

much smaller block network—200 to 300

meters [656 to 984 feet] as opposed to 400

to 600 meters [1,312 to 1,969 feet] in block

length—which greatly enhances walkabil-

ity,” he says.

“Our objective

was to create

a sustainable

and livable

area for about

500,000 people in

Guangzhou, without

creating a negative

impact on the

surroundings.”

—David Masenten, Heller Manus

Architects, San Francisco, California, USA

A rendering of

Guangzhou’s north axis

IMAGECOURTESYOFHELLERMANUSARCHITECTSIMAGESCOURTESYOFSHOPARCHITECTS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1e4baf98-8227-4c8a-bab9-8130db23fe48-161101131419/85/pmnetwork201503-dl-42-320.jpg)