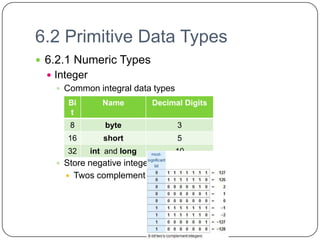

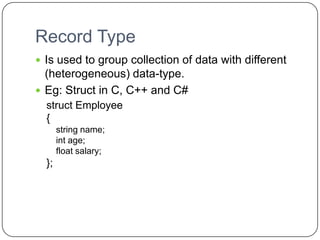

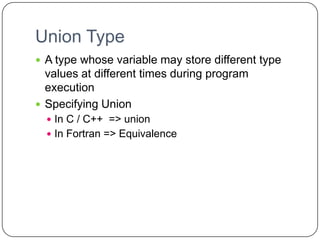

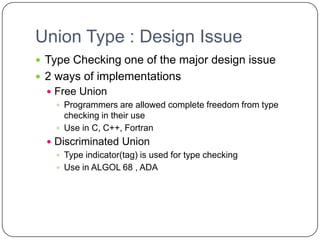

The document discusses various primitive data types including numeric, boolean, character, and string types. It describes integer types like byte, short, int that can store negative numbers using two's complement. Floating point types are represented as fractions and exponents. Boolean types are either true or false. Character types are stored as numeric codes. String types can have static, limited dynamic, or fully dynamic lengths. User-defined types like enumerations and subranges are also covered. The document also discusses array types including their initialization, operations, and implementation using row-major and column-major ordering. Associative arrays are described as unordered collections indexed by keys. Record and union types are summarized.

![Array Types

Homogeneous

Reference – aggregate name & subscript

e.g. arrayName [10]

Element type & Subscript type

Subscript range checking

Subscript lower binding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-8-320.jpg)

![Arrays and Indices

Ada :

e.g. name (10) : Array? Element?

Ordinal Type subscript : e.g. day(Monday)

Perl

Sign @ for array : e.g. @list

Sign $ for scalars : e.g.$list[1]

Negative subscript

+ve subscript 0 1 2 3 4

Array’s 0 1 2 3 4

Element

-ve subscript -5 -4 -3 -2 -1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-9-320.jpg)

![Array Initialization

Languag Example

e

Fortran Integer, Dimension(3) :: List = (/0, 5, 5/)

95

C int list [ ] = {4, 5, 6, 83};

C, C++ char name [ ] = “freddie”;

char *name [ ] = (“Bob”, “Jake”, “Darcie”); //pointer

Java String[ ] names = [“Bob”, “Jake”, Darcie”];

Ada List : array (1..5) of Integer := (1, 3, 4, 7, 8);

Bunch : array (1..5) of Integer := (1 => 17, 3 => 34, others =>

List Comprehensions of Python

0);

Syntax : [expression for iterate_var in array if condition ]

Example :[x*x for x in range (12) if x %

3 == 0 ]

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11,

12] [0, 9, 36, 81,

[0, 3, 6, 9, 144]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-11-320.jpg)

![Rectangular & Jagged Array

Rectangular Array Jagged Array

Fortran, Ada, C# C, C++, Java, C#

myArray [3, 7] myArray [3] [7]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-13-320.jpg)

![6.5.7 Slices

Python: mat 0 1 2

0 1 2 3

1 4 5 6

2 7 8 9

mat [1] -> [4, 5, 6]

mat [0] [0 : 2] -> [1 ,2]

vecto 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

r

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 17

vector [0 : 8 : 2] -> [2 ,6, 10,

14]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-14-320.jpg)

![6.5.9 Implementation of Array Types

Array : 3 4 7 Row Major Order Column Major Order

3 4 7 34 7

6 2 5 6 2 5 6 2 5

1 3 8 1 3 8 1 3 8

3, 4, 7, 6, 2, 5, 1, 3, 8 3, 6, 1, 4, 2, 3, 7, 5, 8

location(a [i, j]) = a 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

adress of a[1, 1] + (( 1

((# of rows above ith row) 2

3

* (size of row)) + 4

(# of columns left jth column))

5 X

* element size) 6

location (a [5, 6]) Adress of a[1, 1] + 4 9 + 5 ) x element

= (( x size)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-15-320.jpg)

![Associative Arrays

An unordered collection of data elements that

are indexed by an equal number of values called

keys.

Each element is a pair of entities (key , value)

Key Value

Eujinn 70

Marry 99 => Dataset[“Eujinn”] = 70;

Joanne 55 => Dataset[“Marry”] = 99;

Johnny 41 => Dataset[“Joanne”] = 55;

=> Dataset[“Johnny”] = 41;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-16-320.jpg)

![Associative Array : Operation

Assignments

$salaries{“Perry”} = 58850; //In Perl

salaries[“Perry”] = 58850; //In C++

Delete

delete $salaries{“Gary”}; //In Perl

salaries.erase(“Gary”); //In C++

Exists

If(exists $salaries{“Shelly”}) … //In Perl

If( salaries.find(“Shelly”)) //In C++](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-18-320.jpg)

![Union Type : Implementation

Implemented by using the same address for

every variant

Storage is allocated to largest variant

1110100 0000001 0000000 0000000

0 1 0 0

C[0] => 232 C[1] = 3

a => 100010 (11111010002)

*32 bits is allocated becaus

int has larger size](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/plc1-111208104143-phpapp01/85/Plc-1-24-320.jpg)