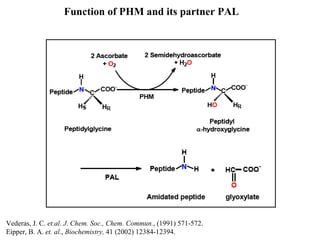

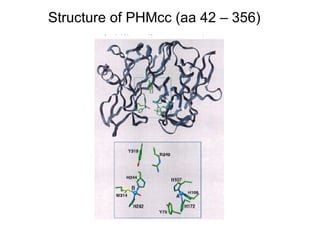

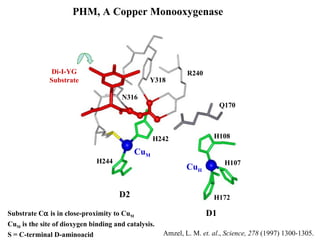

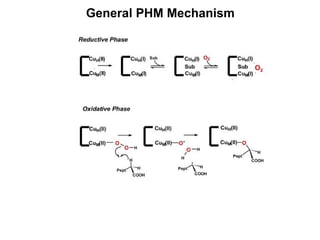

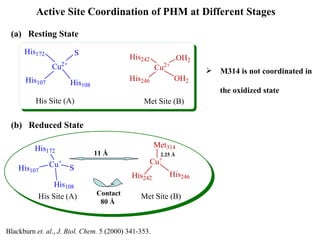

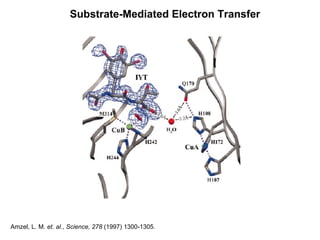

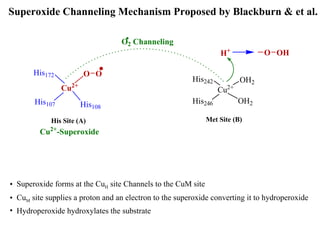

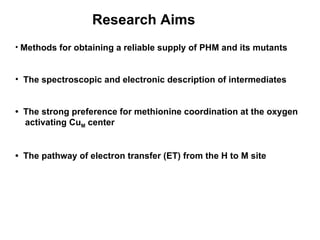

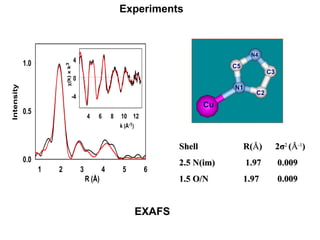

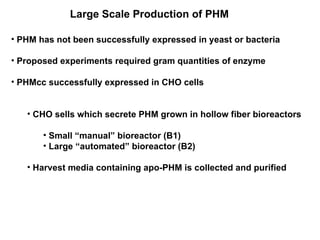

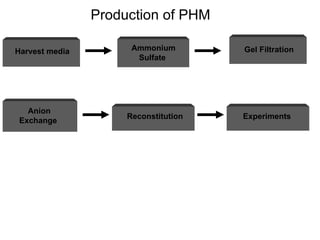

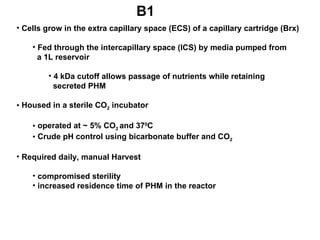

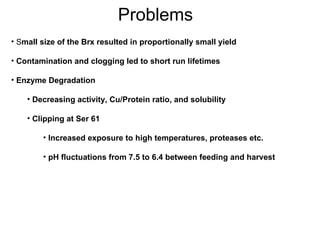

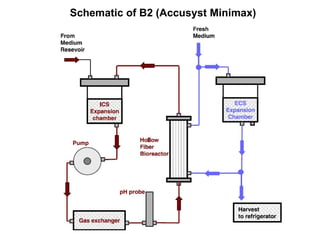

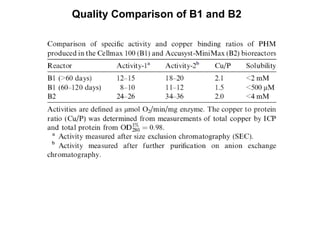

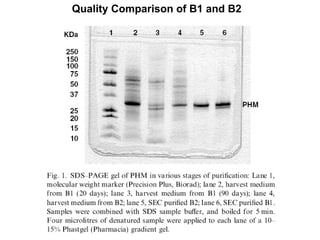

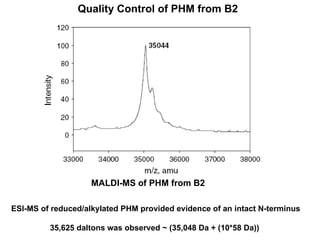

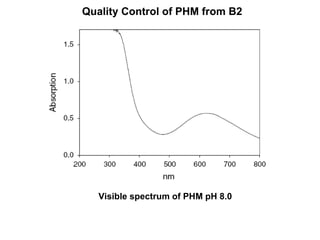

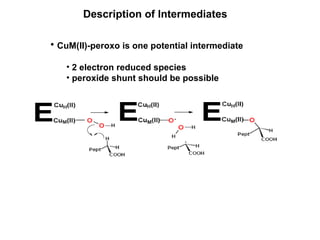

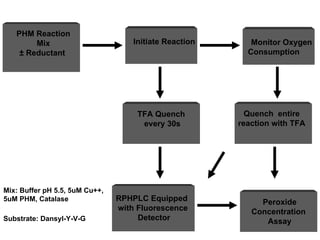

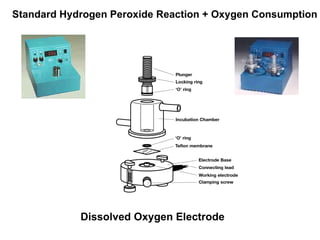

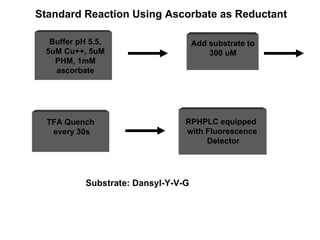

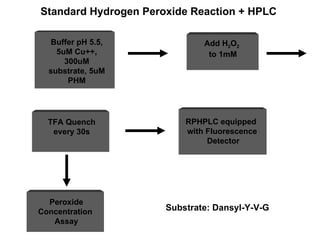

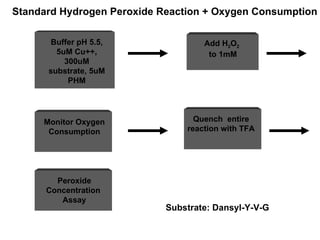

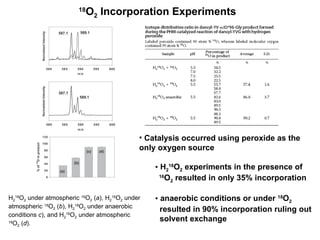

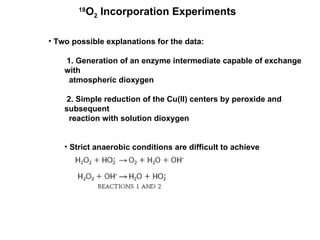

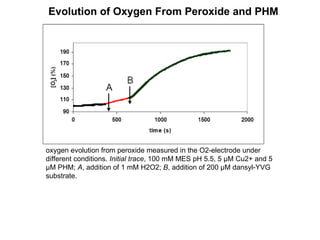

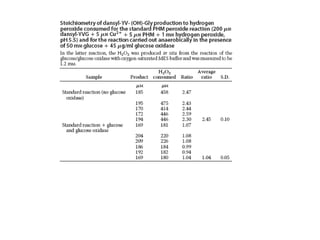

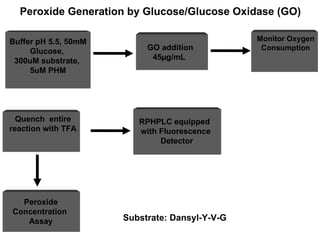

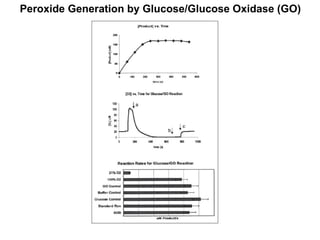

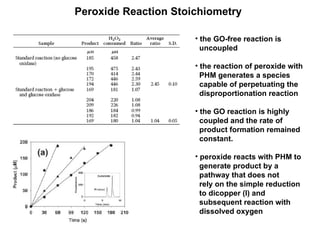

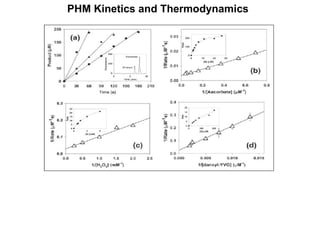

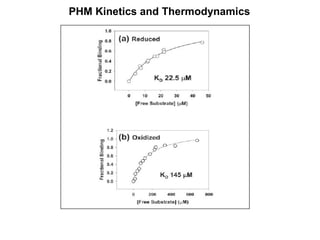

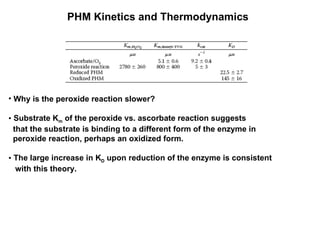

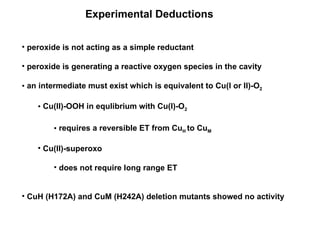

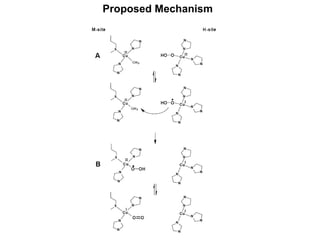

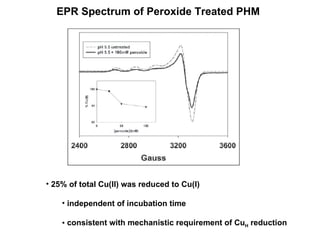

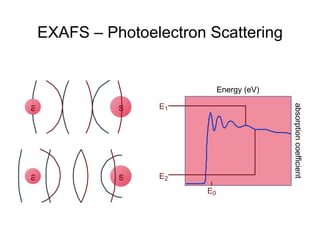

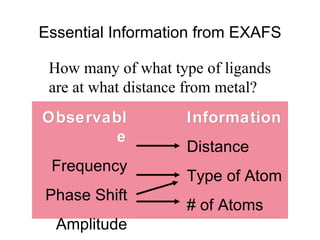

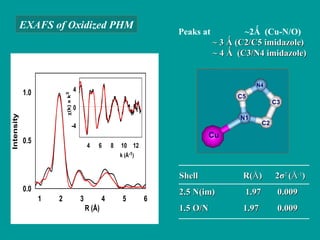

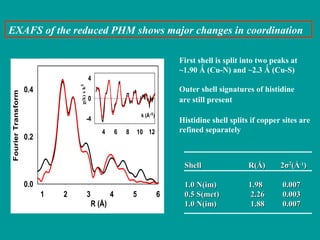

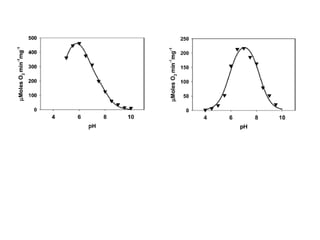

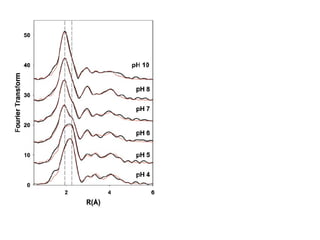

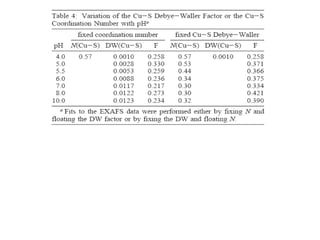

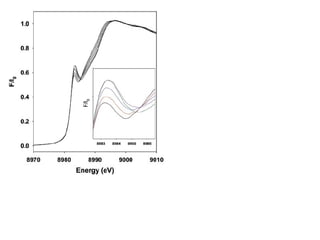

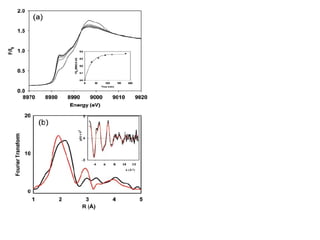

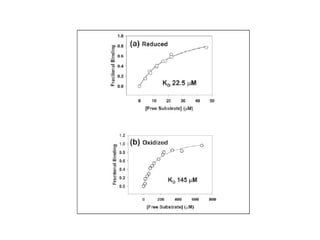

The document details the research on peptidylglycine hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM), focusing on its production, characterization, and mechanistic studies. It outlines various methods to optimize enzyme production in bioreactors, discusses the roles of copper and substrate interactions in catalysis, and presents findings related to electron transfer and reaction intermediates. Additionally, it describes experimental techniques used to investigate enzyme kinetics and the impact of pH on enzyme activity and stability.