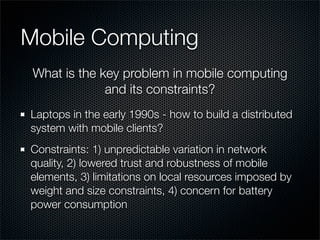

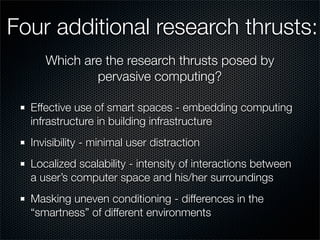

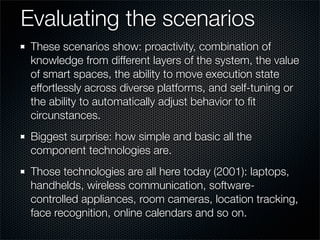

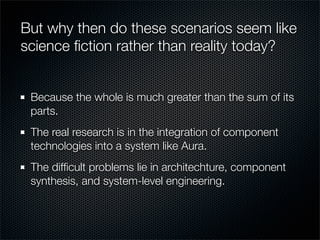

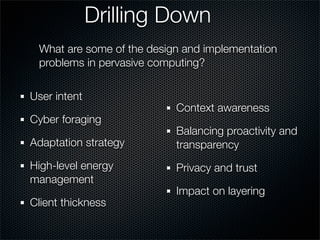

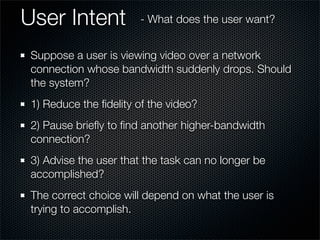

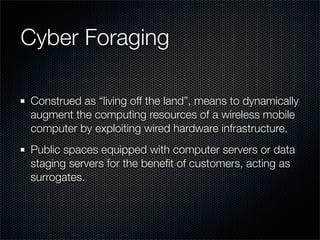

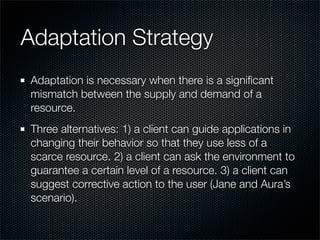

The document discusses pervasive computing, defined as an environment saturated with computing capabilities integrated seamlessly with human users. It outlines the challenges faced by previous technologies like distributed systems and mobile computing, emphasizing the need for integration of these component technologies into a cohesive system for effective functionality. Key research areas include context awareness, energy management, user intent, and privacy, highlighting the complexities and future challenges in developing such systems.