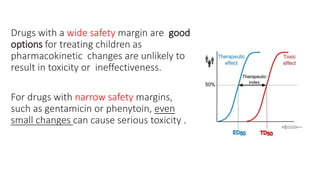

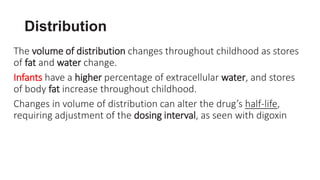

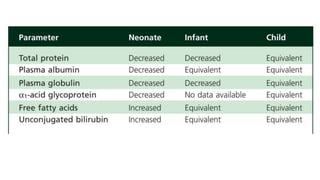

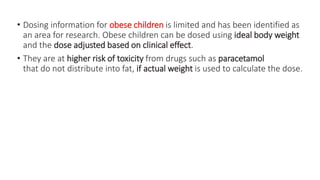

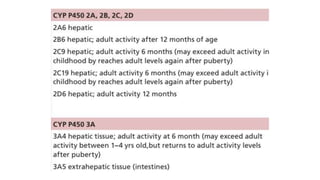

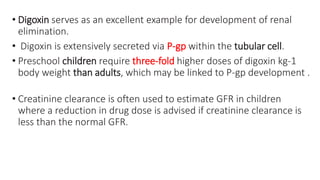

The document discusses the critical lack of pediatric clinical trials and dosing information, emphasizing that drug use in children often occurs off-label, increasing the risk of adverse effects. It highlights the complexities of dosing in children due to variable pharmacokinetics, and stresses the need for tailored dosing regimens based on individual clinical responses. The document also outlines the importance of understanding absorption, metabolism, and elimination processes as they differ significantly from adults, necessitating careful consideration when prescribing medications to children.