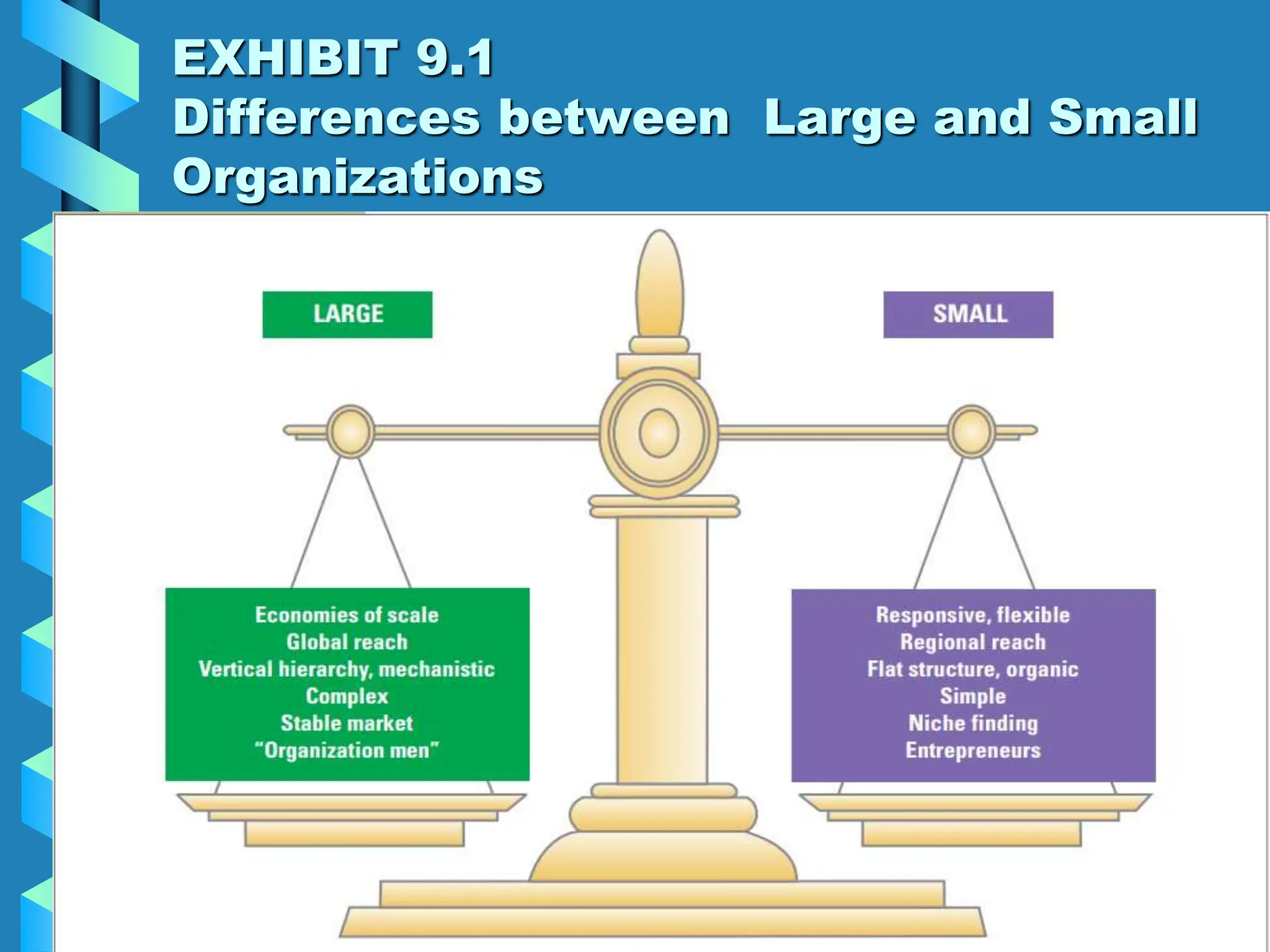

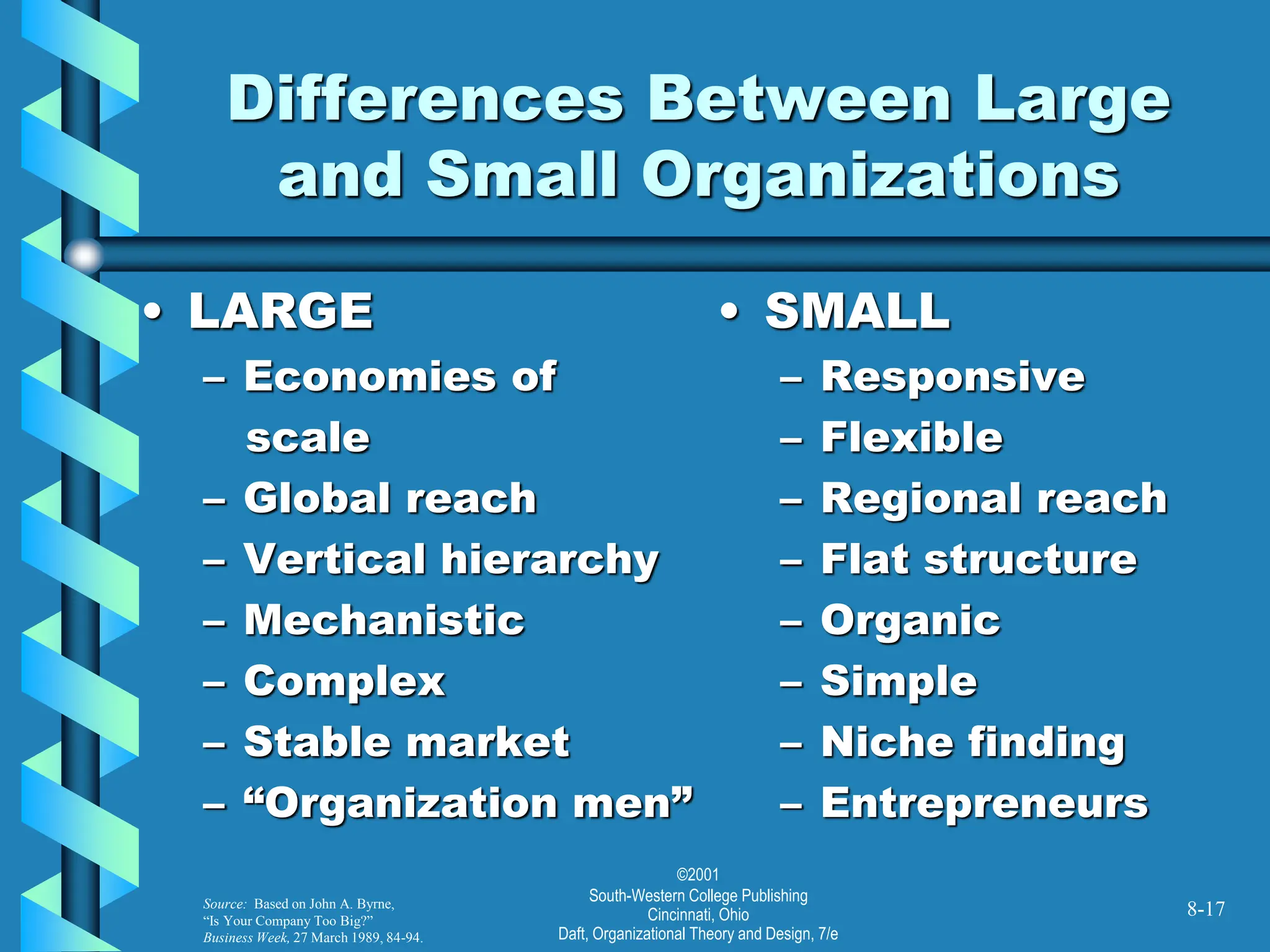

This chapter discusses the relationship between the size of organizations and their structure and control mechanisms, exploring the advantages and disadvantages of both large and small organizations. It outlines an organizational life cycle consisting of four stages: entrepreneurial, collectivity, formalization, and elaboration, each characterized by specific challenges and structural needs. Additionally, the chapter examines the historical need for bureaucracy in large organizations and the causes of organizational decline, along with strategies for managing downsizing.