The document defines operations research and discusses its history and applications. It originated during World War II to optimize limited military resources. Operations research uses mathematical modeling to aid decision making. It defines problems, formulates models, derives solutions, and implements recommendations. Some key applications include allocating scarce resources optimally and minimizing costs and wait times.

![Cont’d…

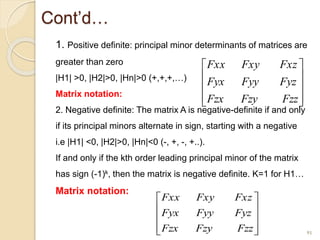

C1 = 2 is the coefficient of non-basic variable x1, and

assume that c1 is subject to change by ∆c1.

Where ∆𝐶1 = 𝐶1

′

− 𝐶1. As you remember to maintain the optimality

condition all the elements in the ∆j row should be all non-negative.

In this case:

56

∆j1 ≥ 0 ∆𝐶1 ≤ 2

𝑍1 − 𝐶1

′

≥ 0𝐶1

′

− 𝐶1 ≤ 2

𝑍1 − (𝐶1 + ∆𝐶1) ≥ 0𝐶1

′

− 2 ≤ 2

𝑍1 − 𝐶1 − ∆𝐶1 ≥ 0𝐶1

′

≤ 4

4 − 2 − ∆𝐶1 ≥ 0(−∞, 4]

−∆𝐶1 ≥ −2

∆𝐶1 ≤ 2

(−∞, 2)

Therefore, the range over which the parameter (c1) can change

without affecting the current optimal solution x1 = 0 and x2 = 6 is

−∞, 4 .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/operationsresearch-240201055047-0286290a/85/Operations-research-pptx-56-320.jpg)