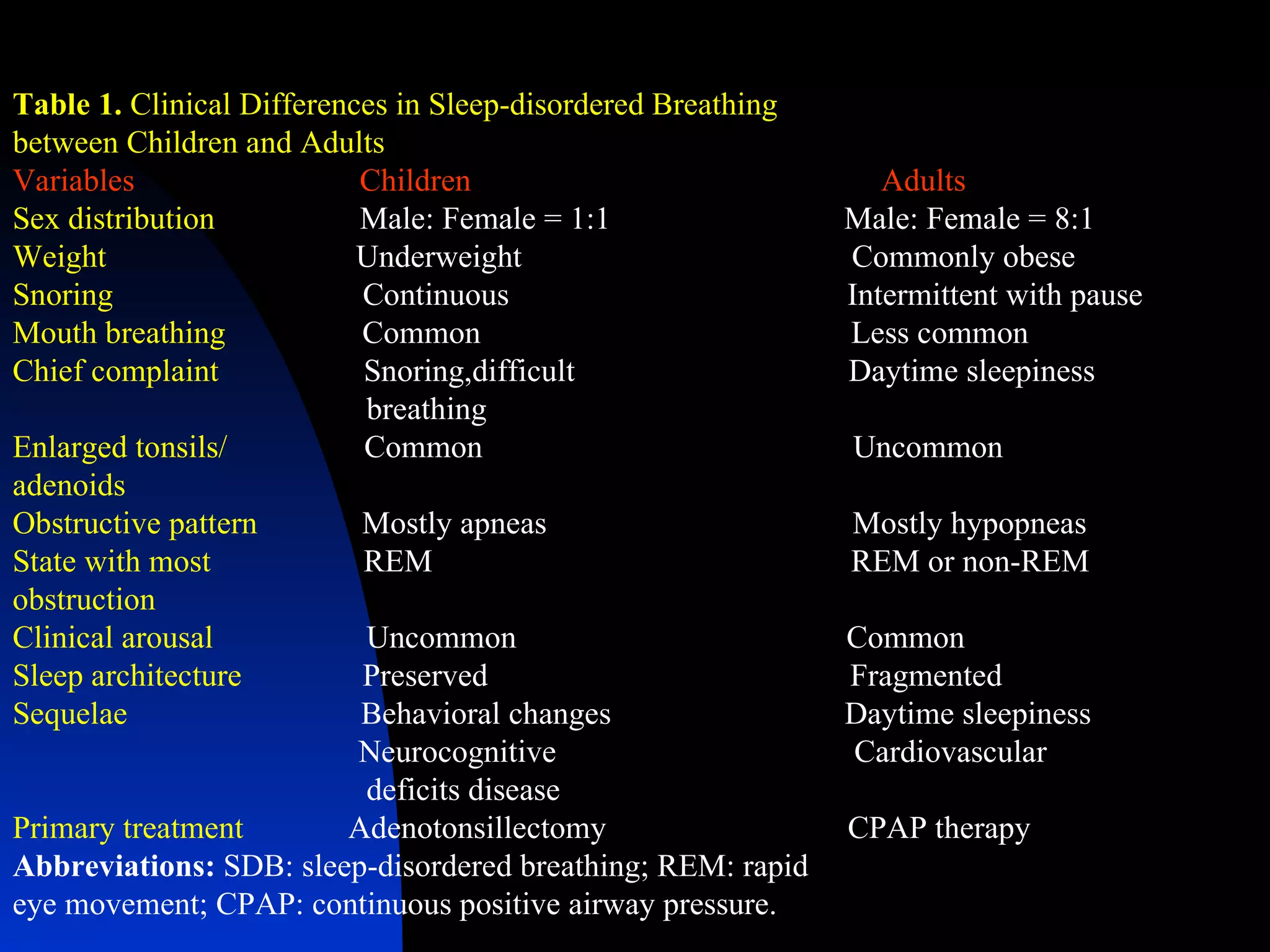

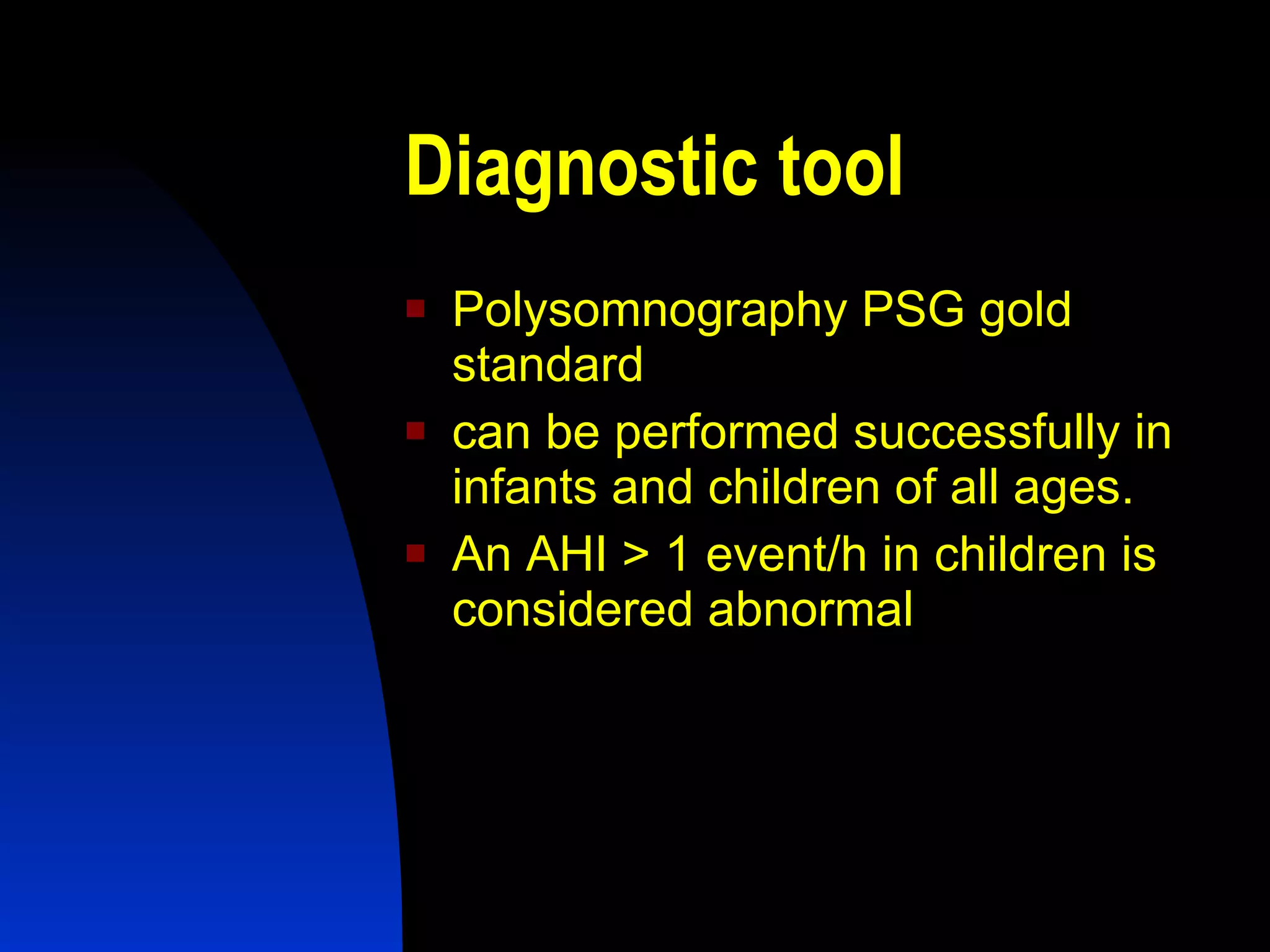

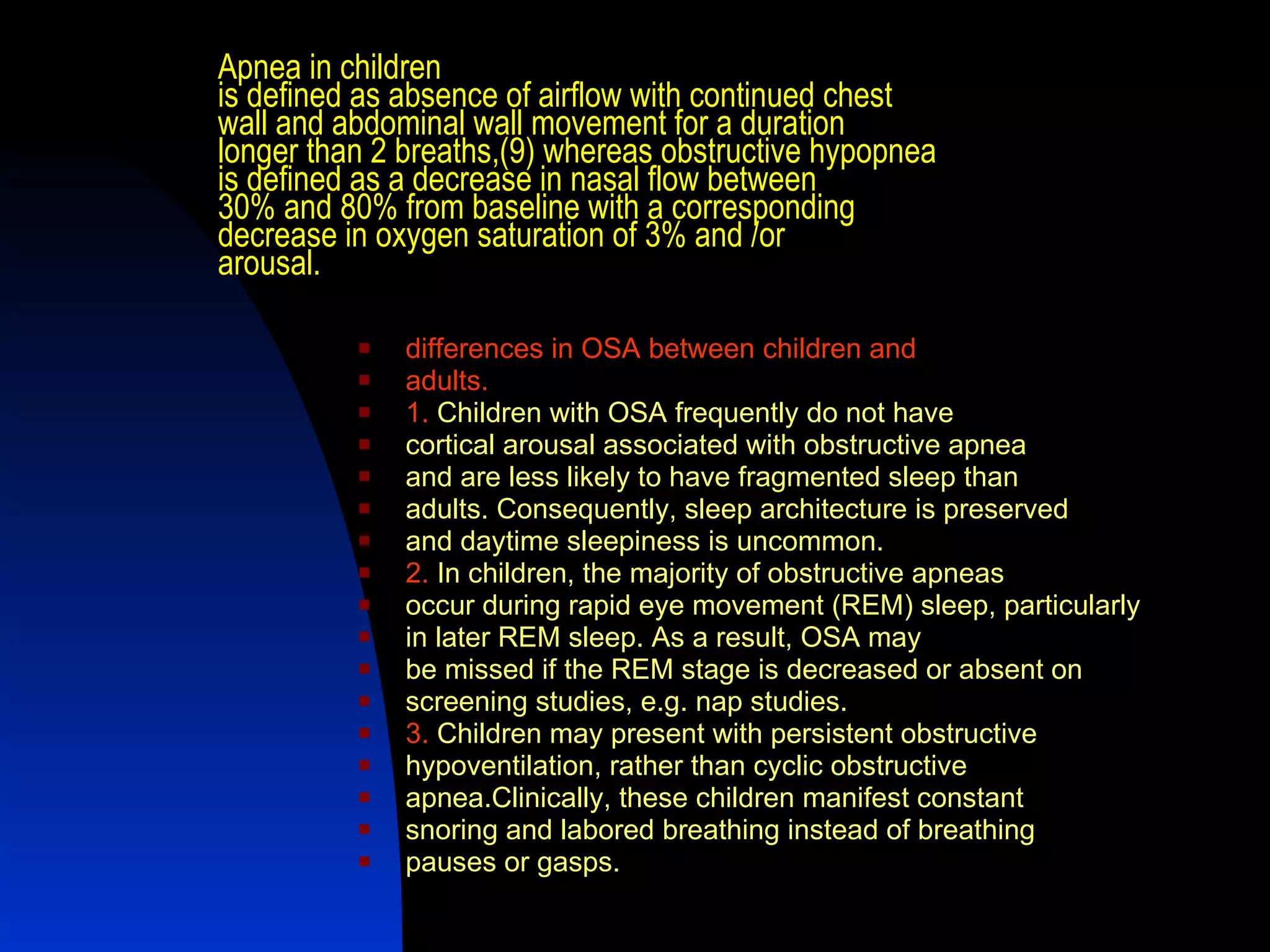

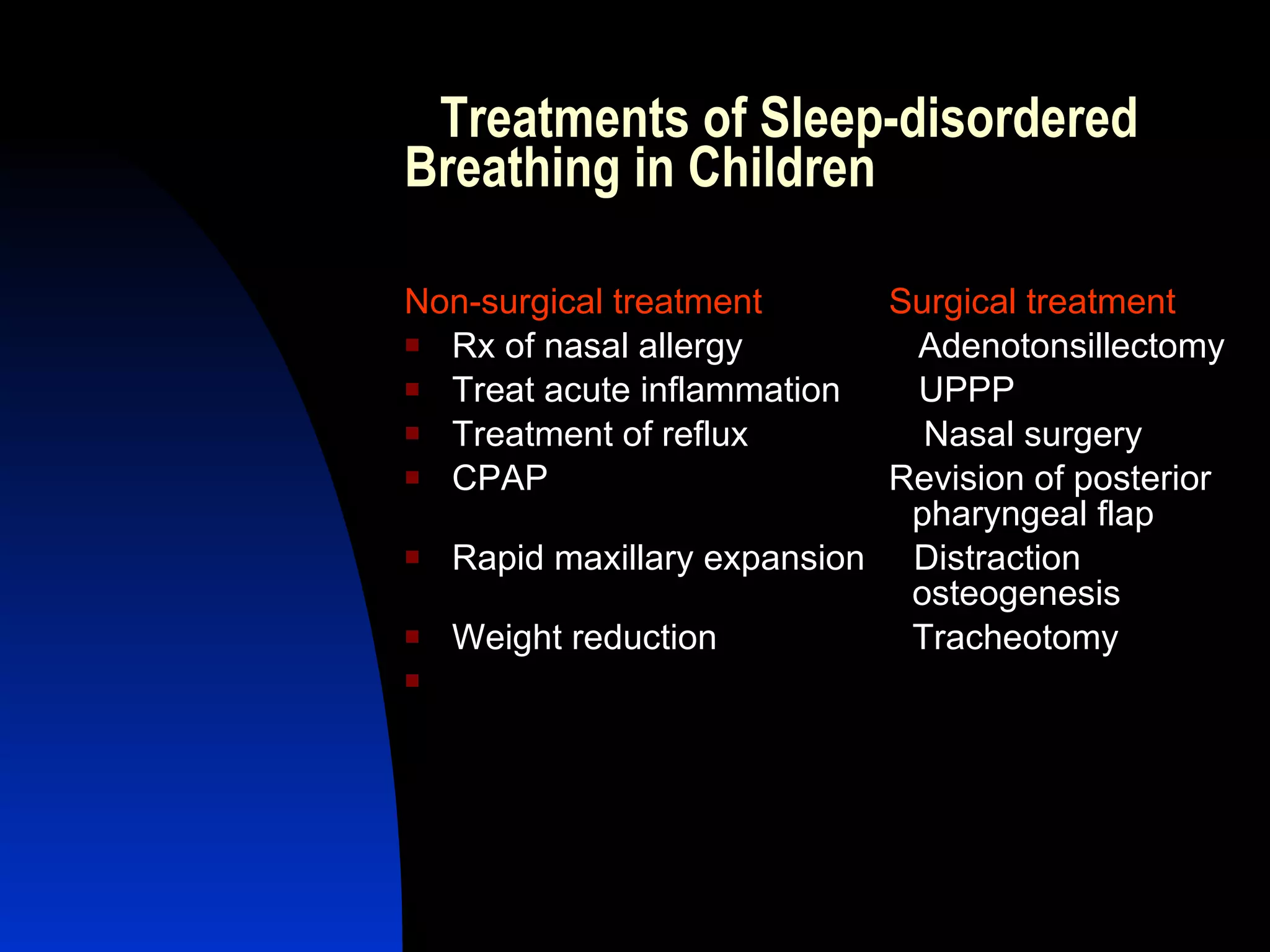

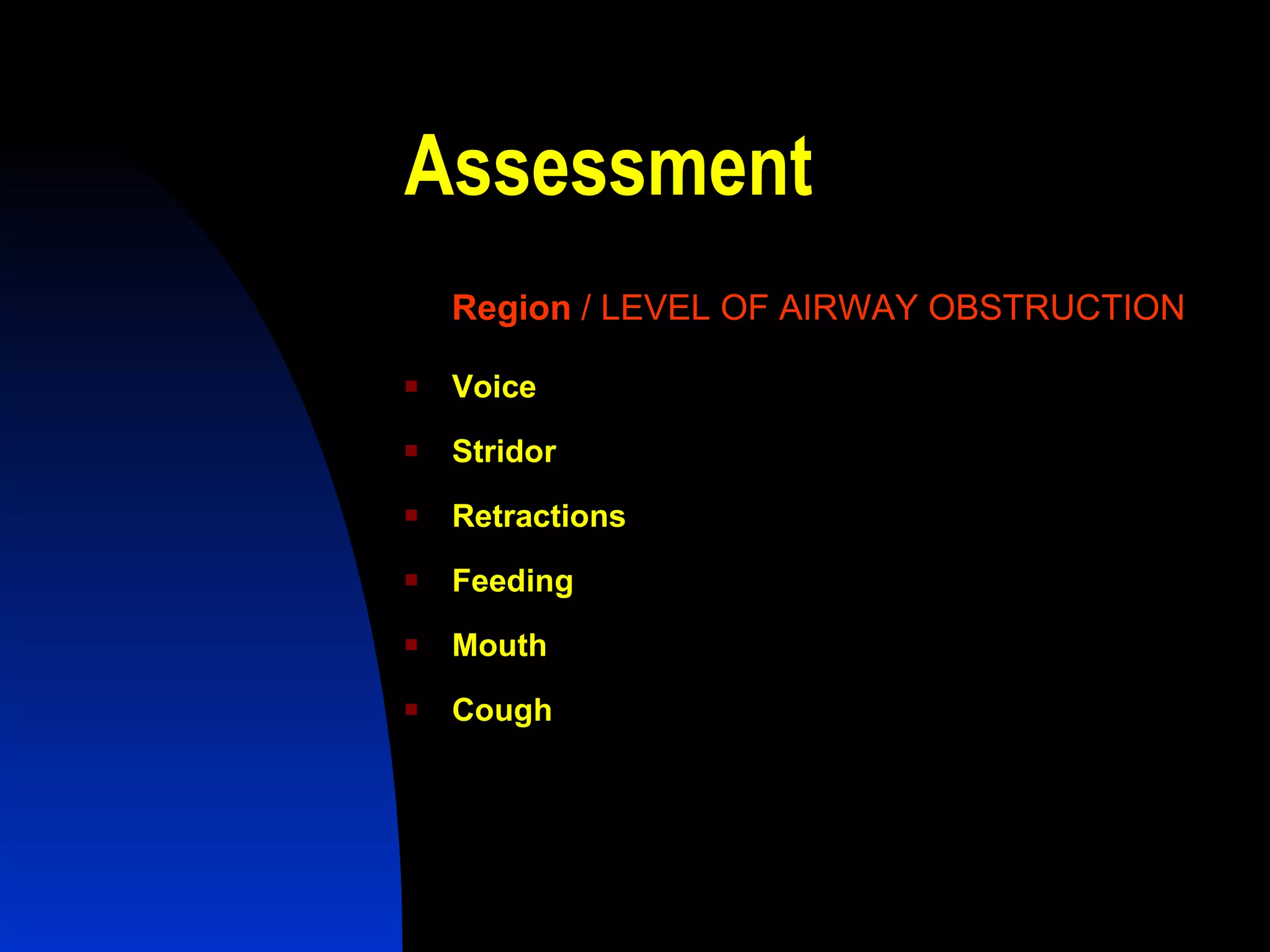

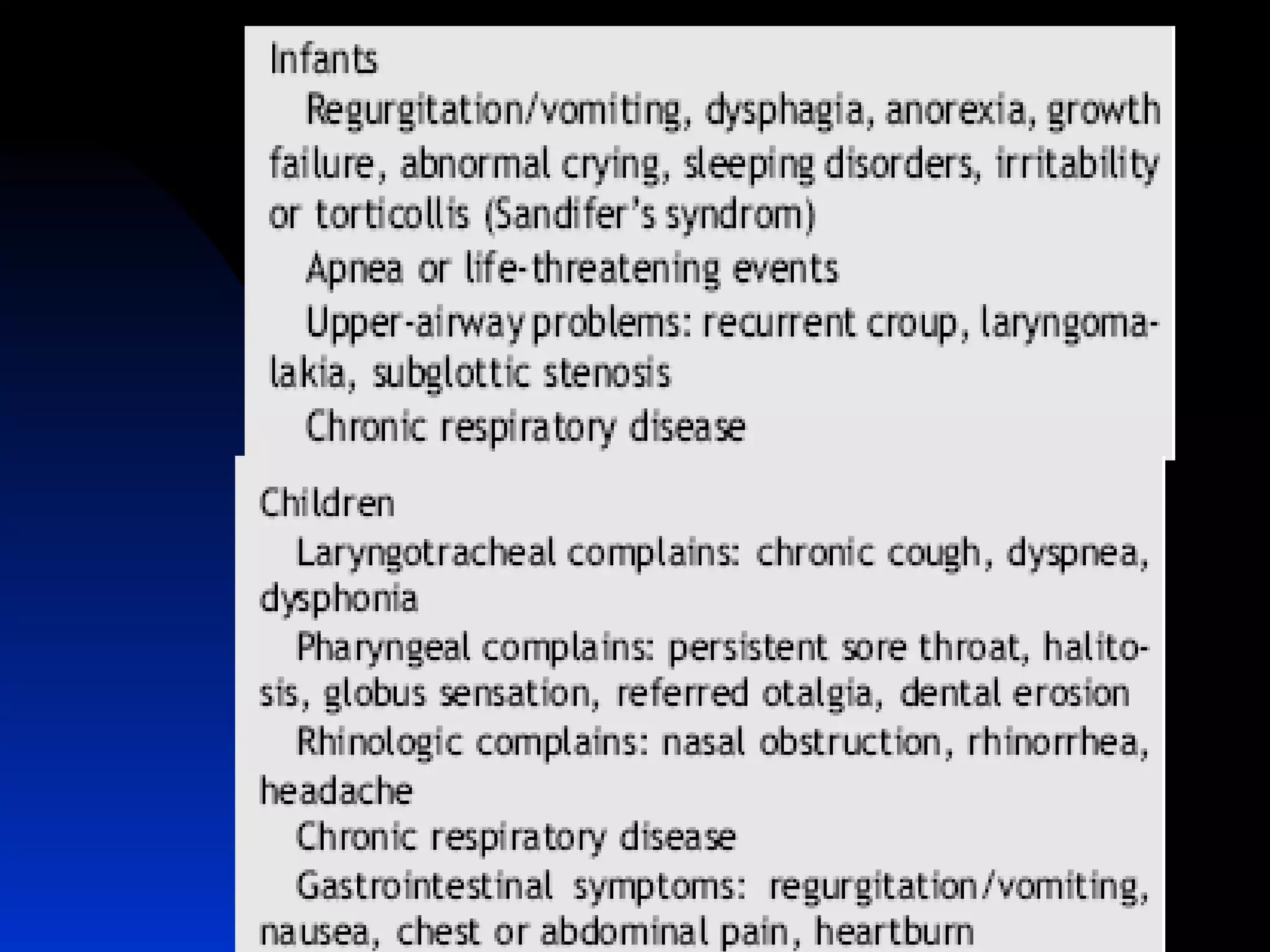

1. The document discusses office-based ENT practices for children, covering diagnostic tools, common conditions, and treatment approaches. Polysomnography is the gold standard for diagnosing sleep disorders, while adenotonsillectomy is often the primary treatment for sleep-disordered breathing.

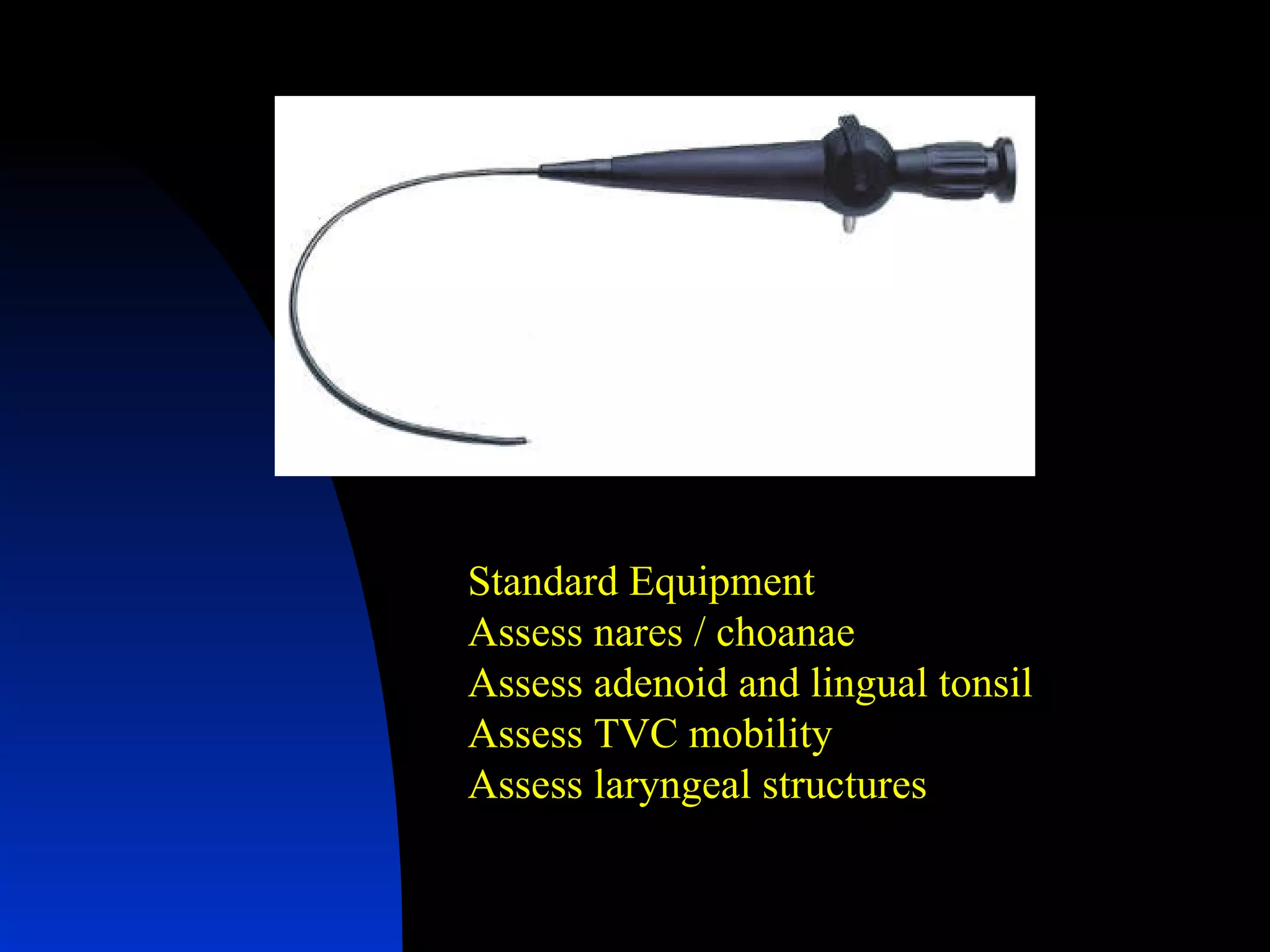

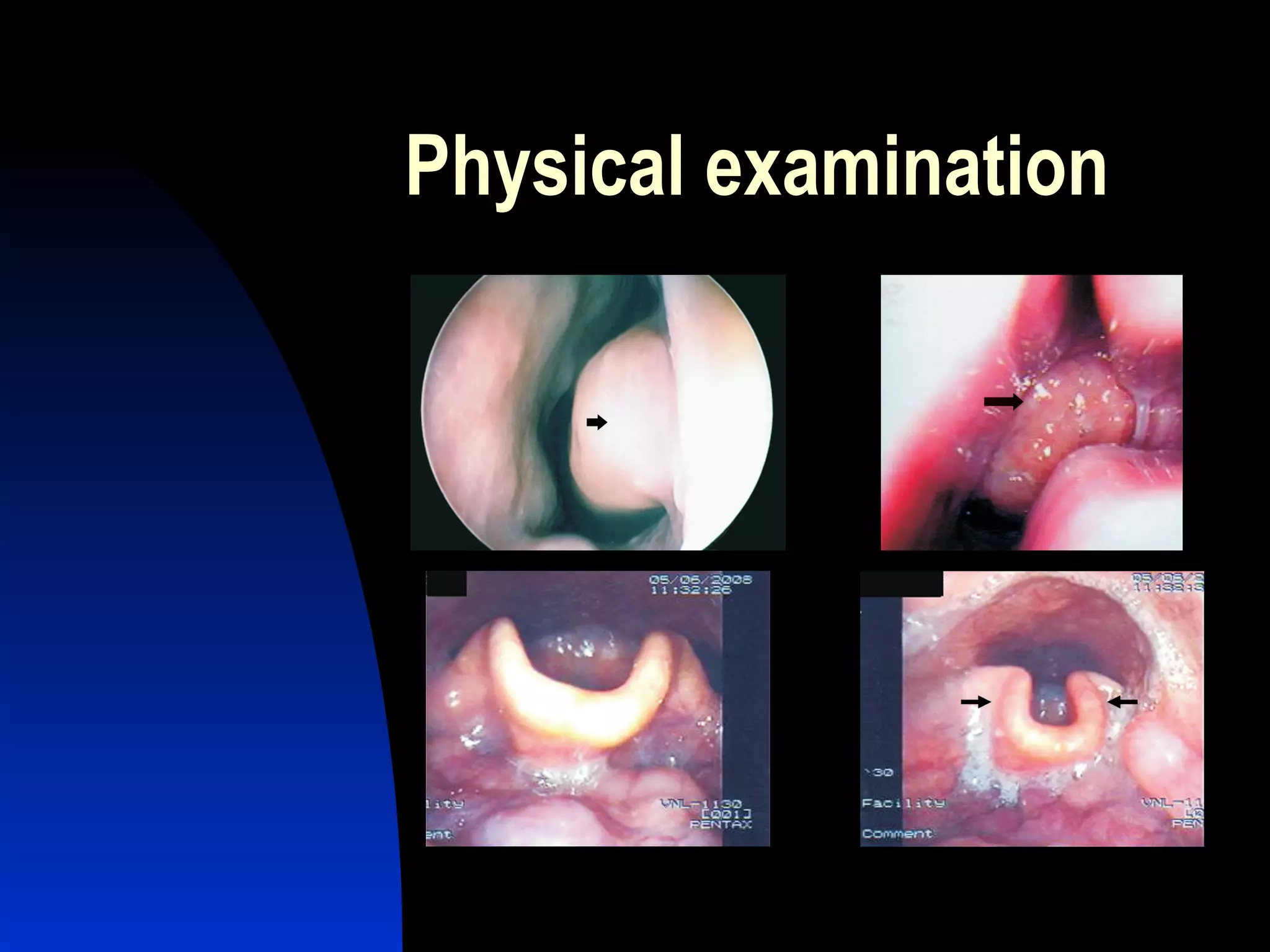

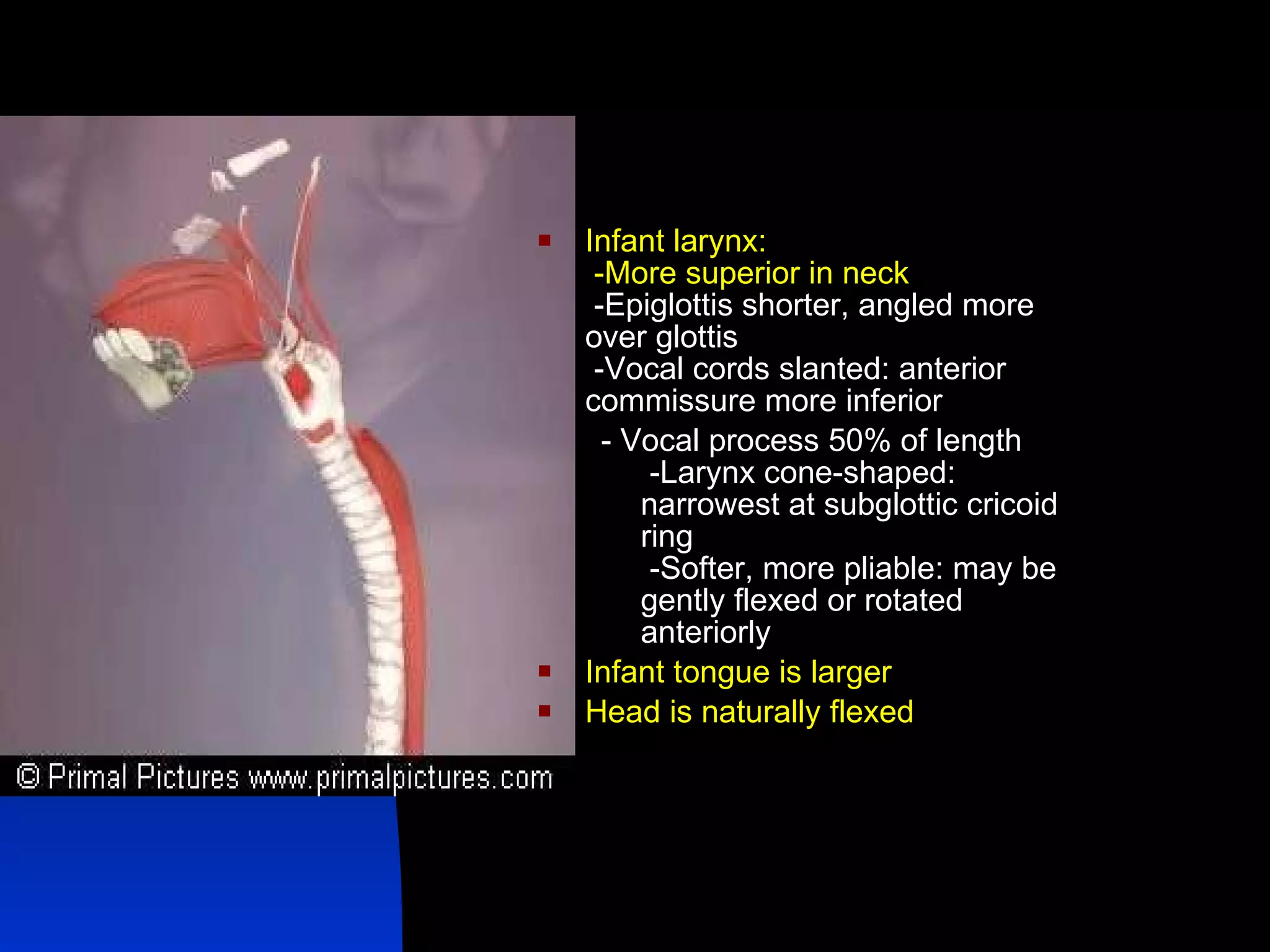

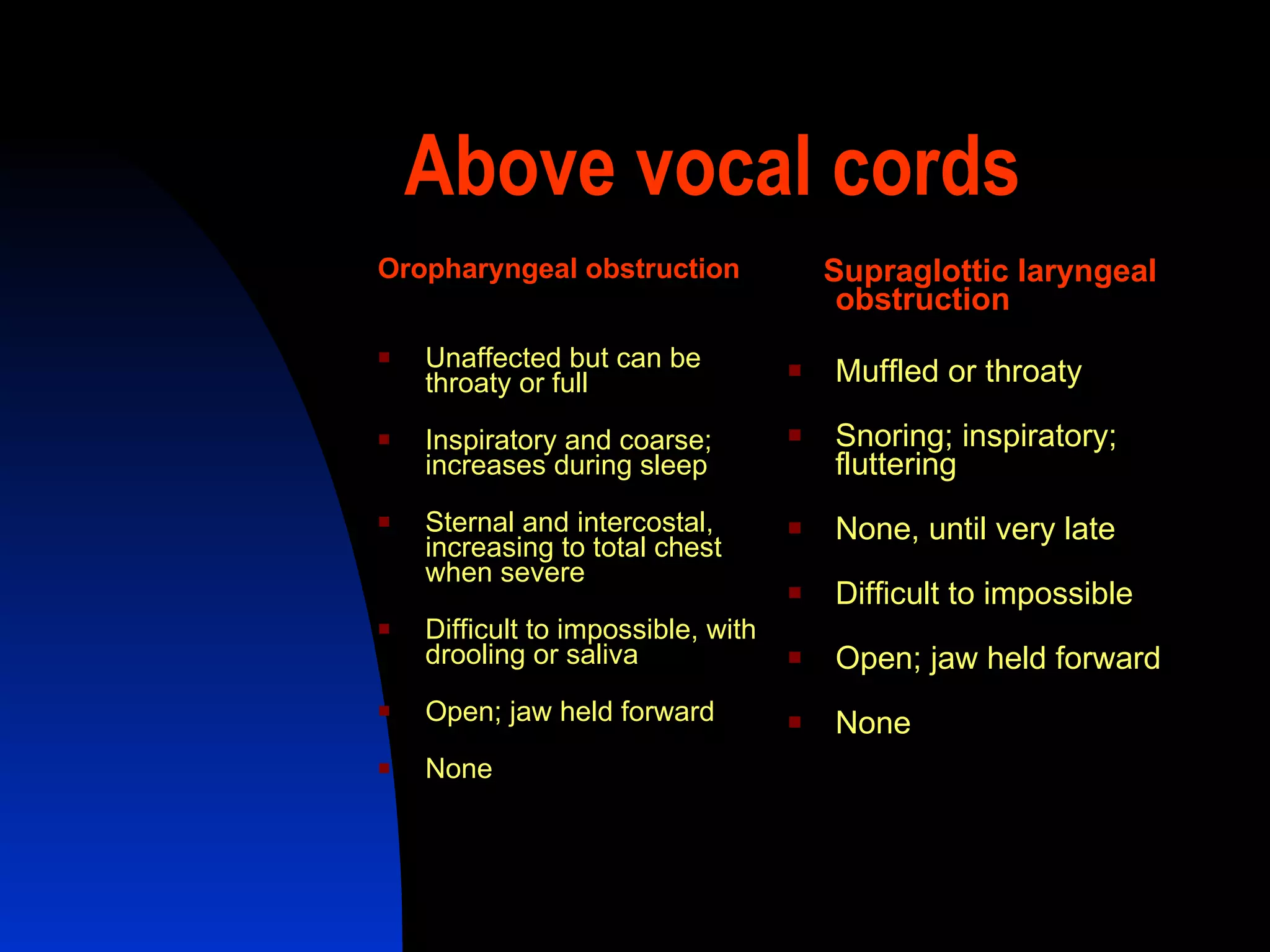

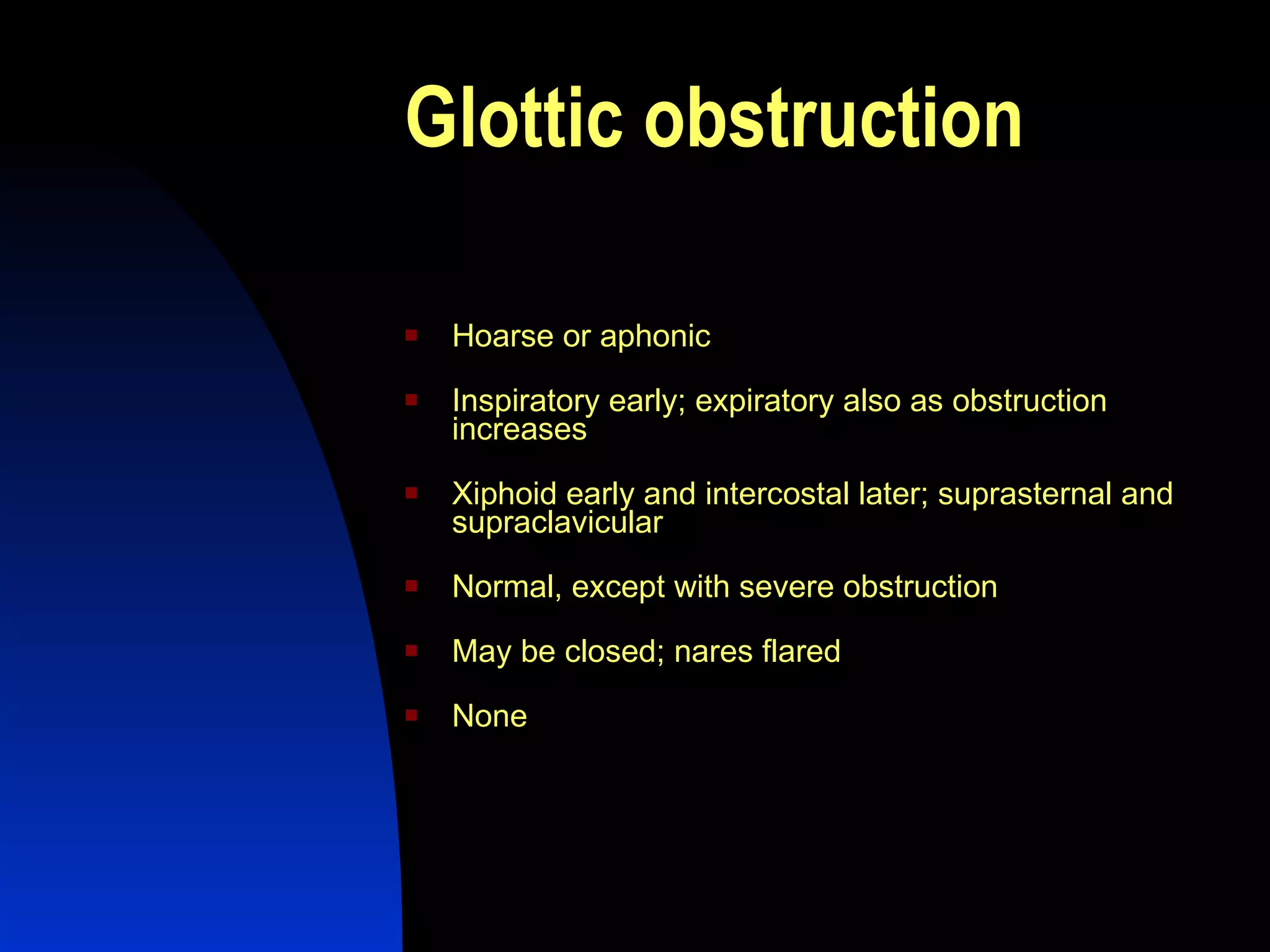

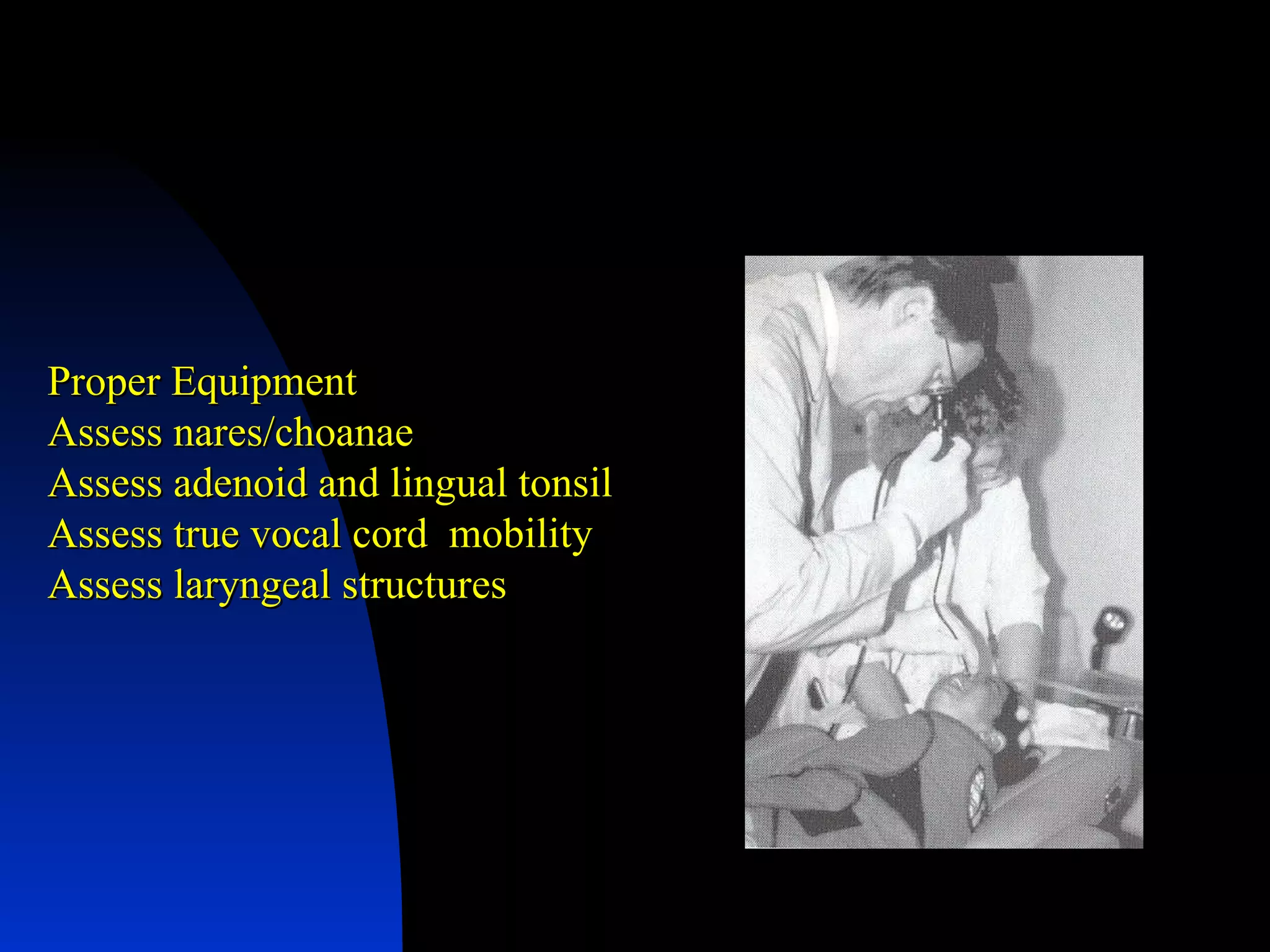

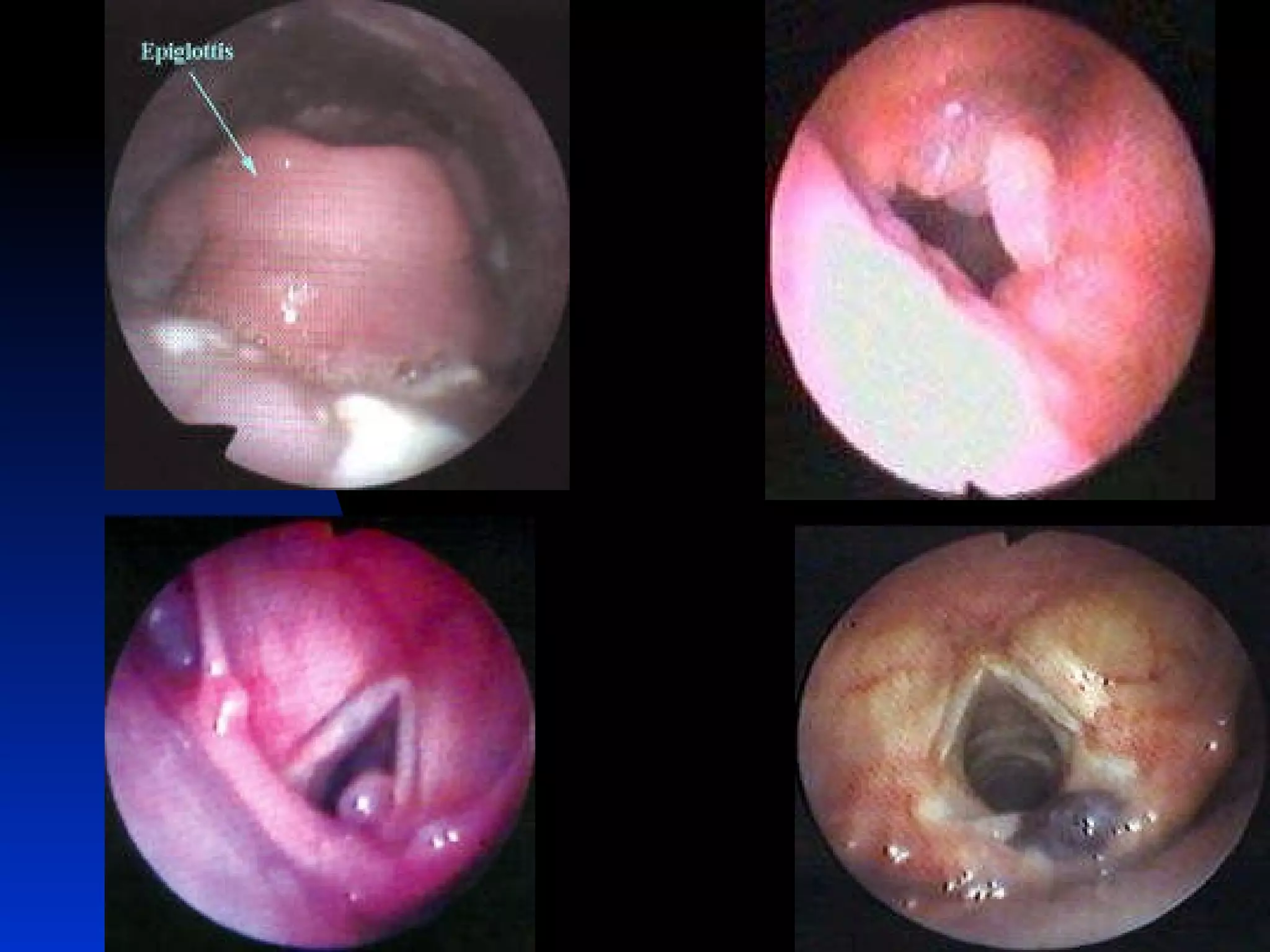

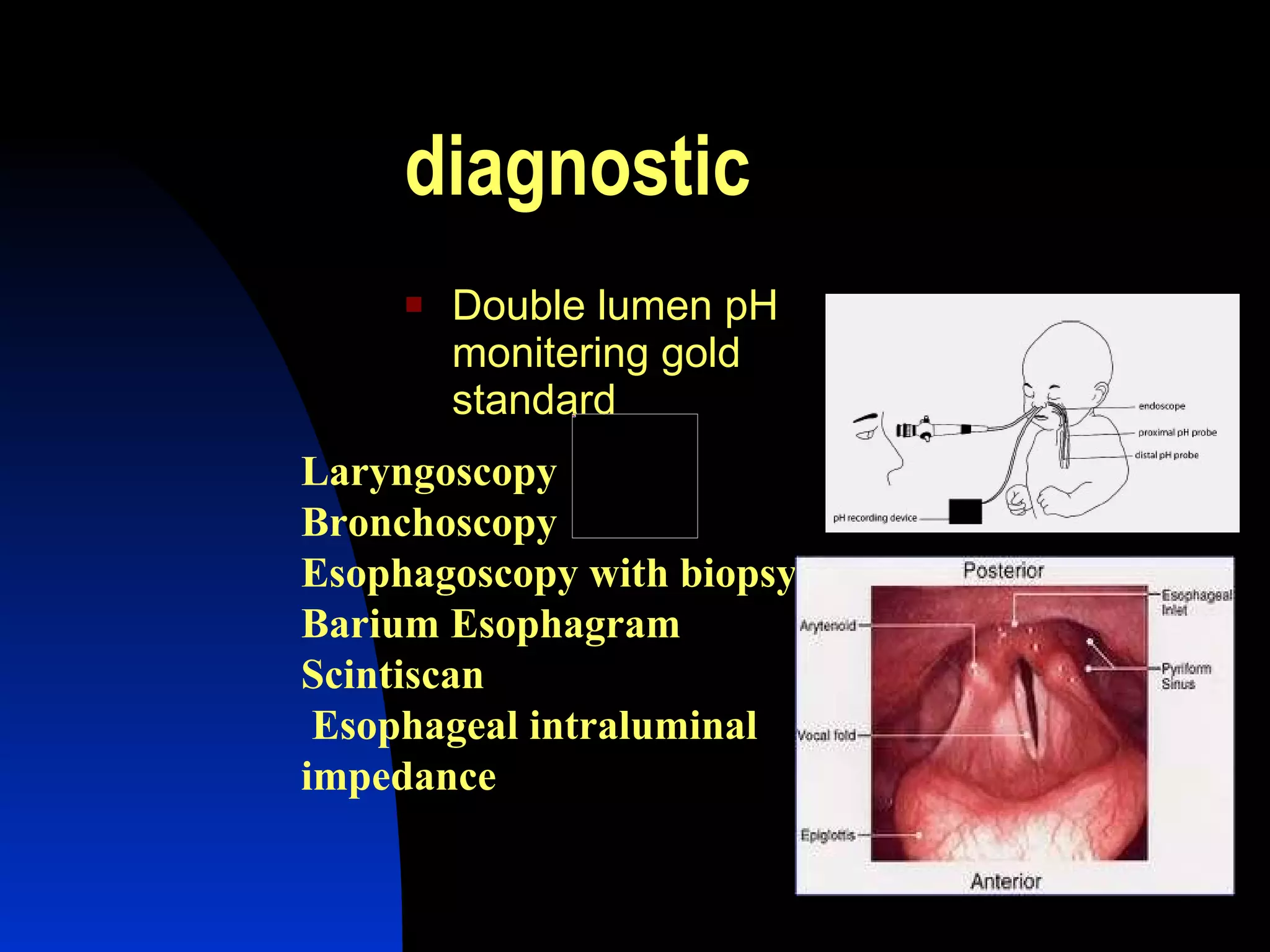

2. Flexible laryngoscopy and other scoping procedures are important for evaluating the airway and detecting issues like laryngomalacia. Swallowing disorders are common in children with neurological conditions and may require videofluoroscopy.

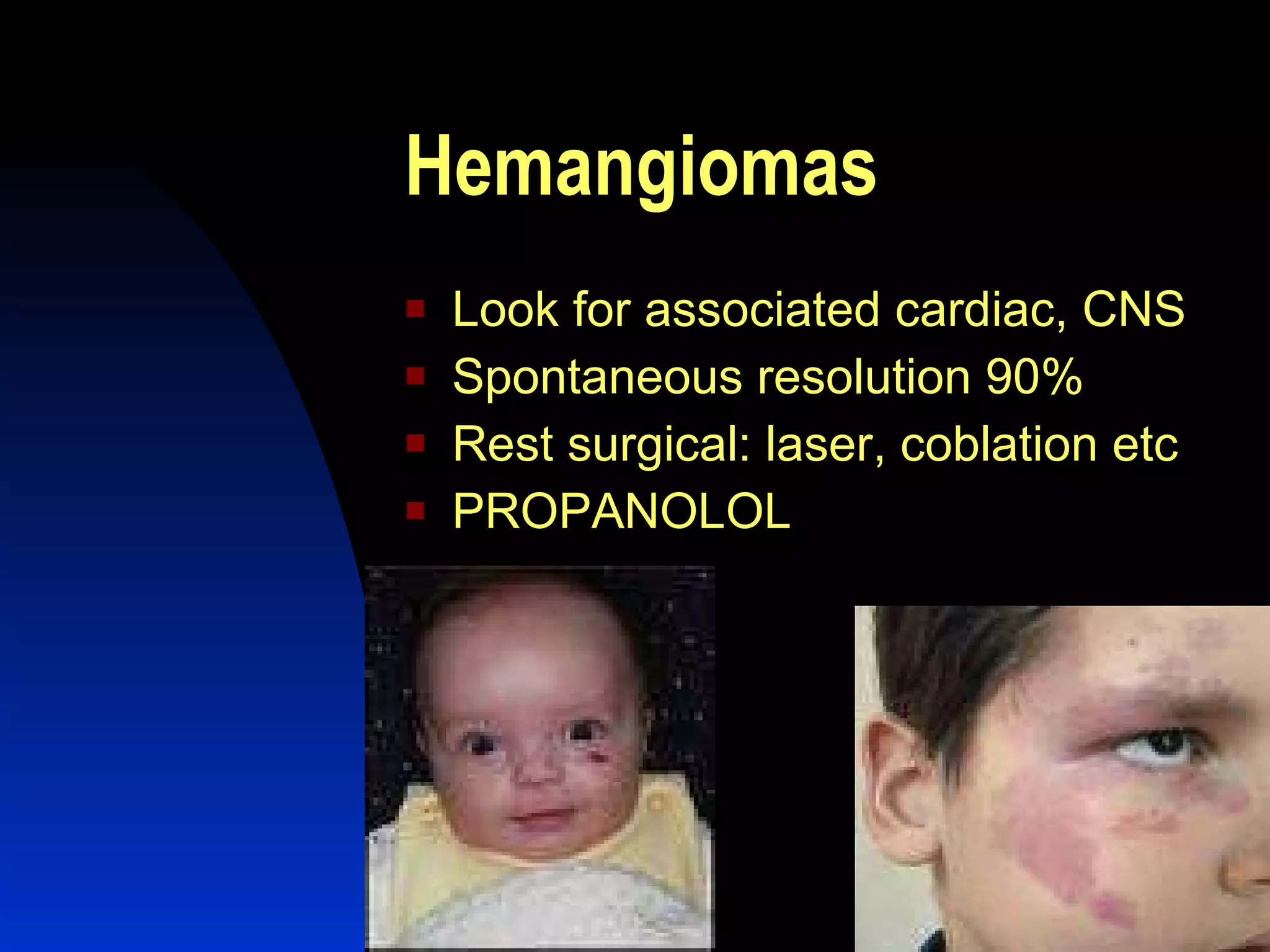

3. Hemangiomas are a frequent congenital issue but often resolve spontaneously. Propranolol is now used to treat hemangiomas in addition to older surgical approaches.

![Evaluation -ABC every pediatric casualty should have flexible scopes Choanal atresias Laryngomalacia Vocal cord & glottic anamolies[?clefts] RRP Subglottic anamolies](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/officebasedentpractiseinchildren2-111119015241-phpapp01/75/Office-based-ent-practise-in-2-30-2048.jpg)

![We Can Only Refine Our Therapeutics When We Refine Our Diagnostic Abilities THANK YOU SHEELU SRINIVAS [email_address] 9900176770](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/officebasedentpractiseinchildren2-111119015241-phpapp01/75/Office-based-ent-practise-in-2-48-2048.jpg)