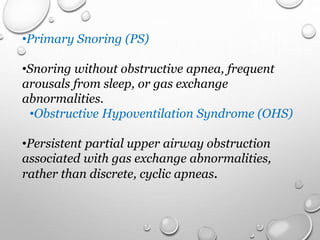

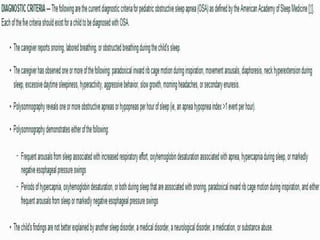

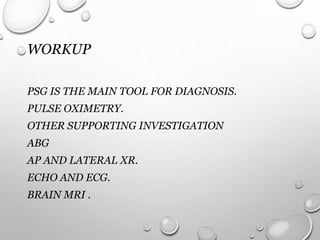

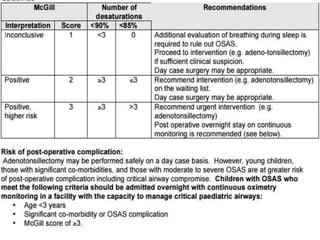

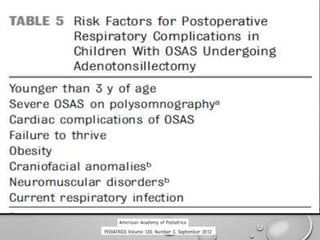

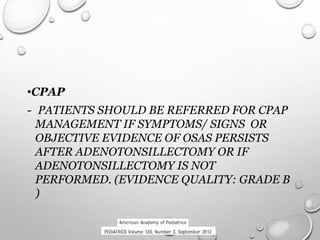

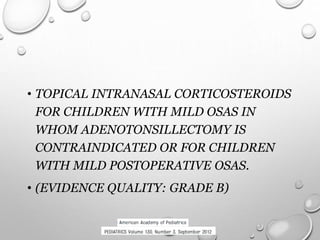

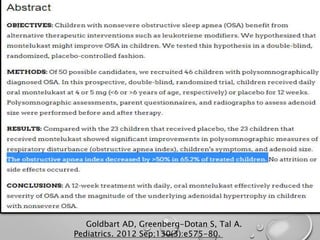

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children refers to the spectrum of repetitive complete or partial obstructions of the airway during sleep that disrupt breathing and sleep architecture. OSA is common in young children ages 2 to 8 years old, affecting approximately 2-3% of children. It is diagnosed if there is a greater than 90% drop in airflow for at least two missed breaths during sleep studies. Treatment involves weight reduction, avoiding sedatives, tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy which is usually first line treatment, and CPAP if symptoms persist after surgery or it is not performed. Children with Down syndrome are particularly at high risk for OSA due to anatomical factors. [/SUMMARY]