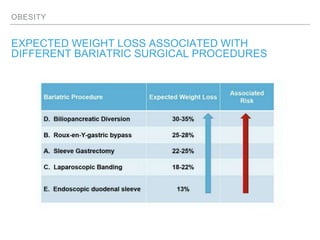

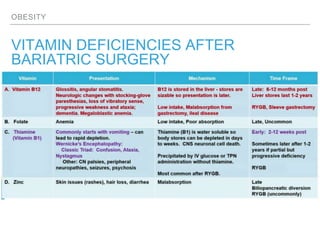

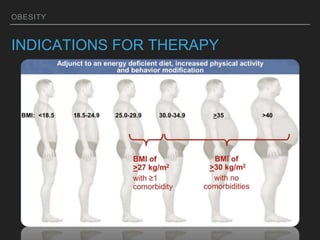

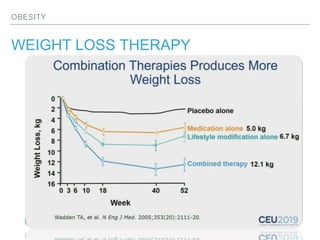

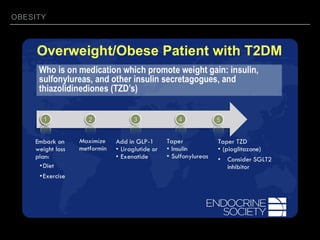

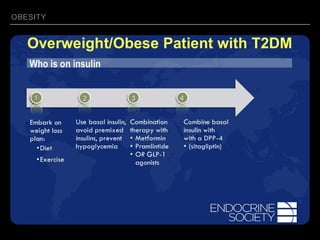

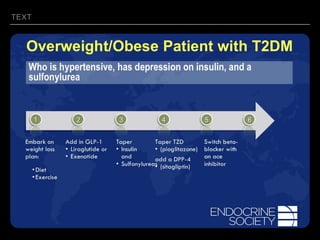

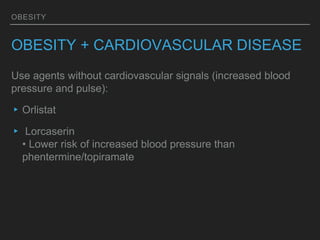

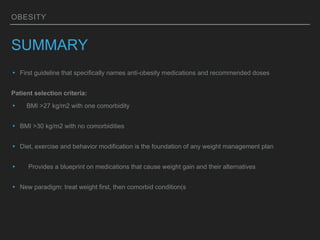

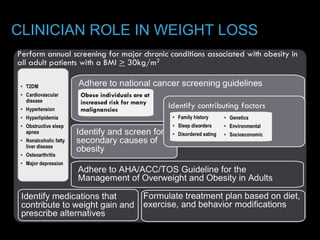

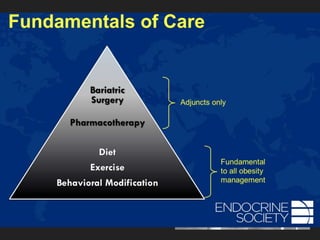

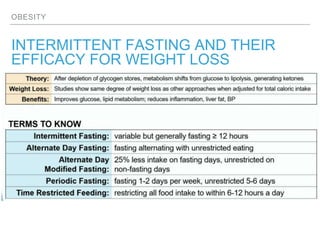

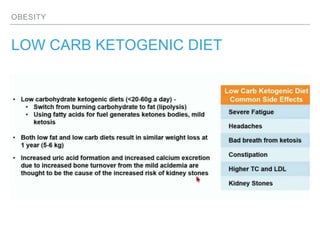

This document discusses obesity, including its definitions, classifications, prevalence, physiology, and management. It provides guidelines for clinicians on their role in weight loss, including counseling strategies to promote behavior change. New guidelines for obesity management are presented, along with selecting appropriate medications based on a patient's comorbidities. Surgical and non-surgical procedures for obesity are outlined, along with expected weight loss and vitamin deficiencies. The role of nutrition, physical activity, behavior therapy, and medical therapy in obesity treatment is also examined.

![OBESITY

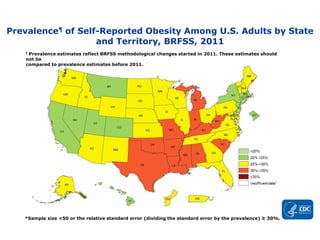

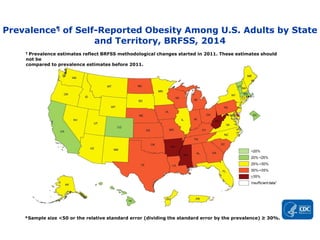

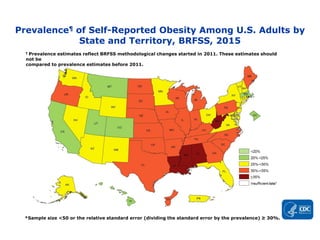

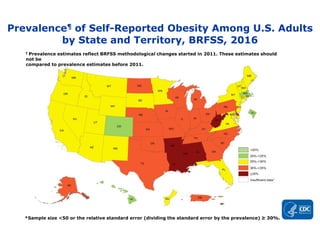

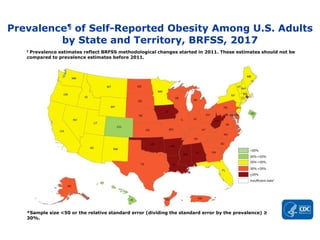

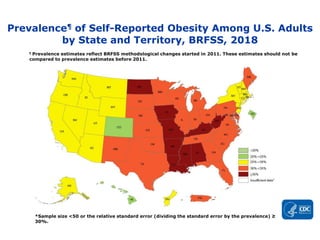

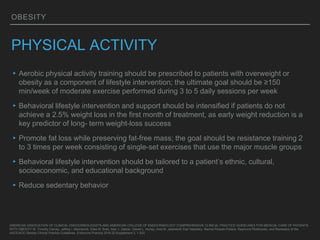

OBESITY PREVALENCE MAPS

▸Adult obesity prevalence by state and territory using self-reported information from the Behavioral

Risk Factor Surveillance System.

▸Obesity is common, serious, and costly

▸The prevalence of obesity was 39.8% and affected about 93.3 million of US adults in 2015~2016.

▸Obesity-related conditions include heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and certain types of

cancer that are some of the leading causes of preventable, premature death. [Read

guidelinesExternal

]

▸The estimated annual medical cost of obesity in the United States was $147 billion in 2008 US

dollars; the medical cost for people who have obesity was $1,429 higher than those of normal

weight

CDC National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) data briefCdc-pdf

PDF-603KB](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mansilla-obesidad-191017185601/85/Obesity-6-320.jpg)

![TEXT

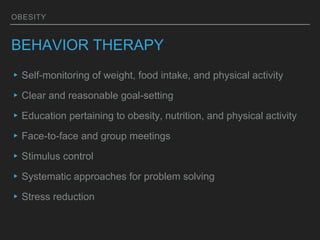

BEHAVIOR THERAPY

▸Cognitive restructuring: cognitive behavioral therapy],

motivational interviewing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mansilla-obesidad-191017185601/85/Obesity-40-320.jpg)