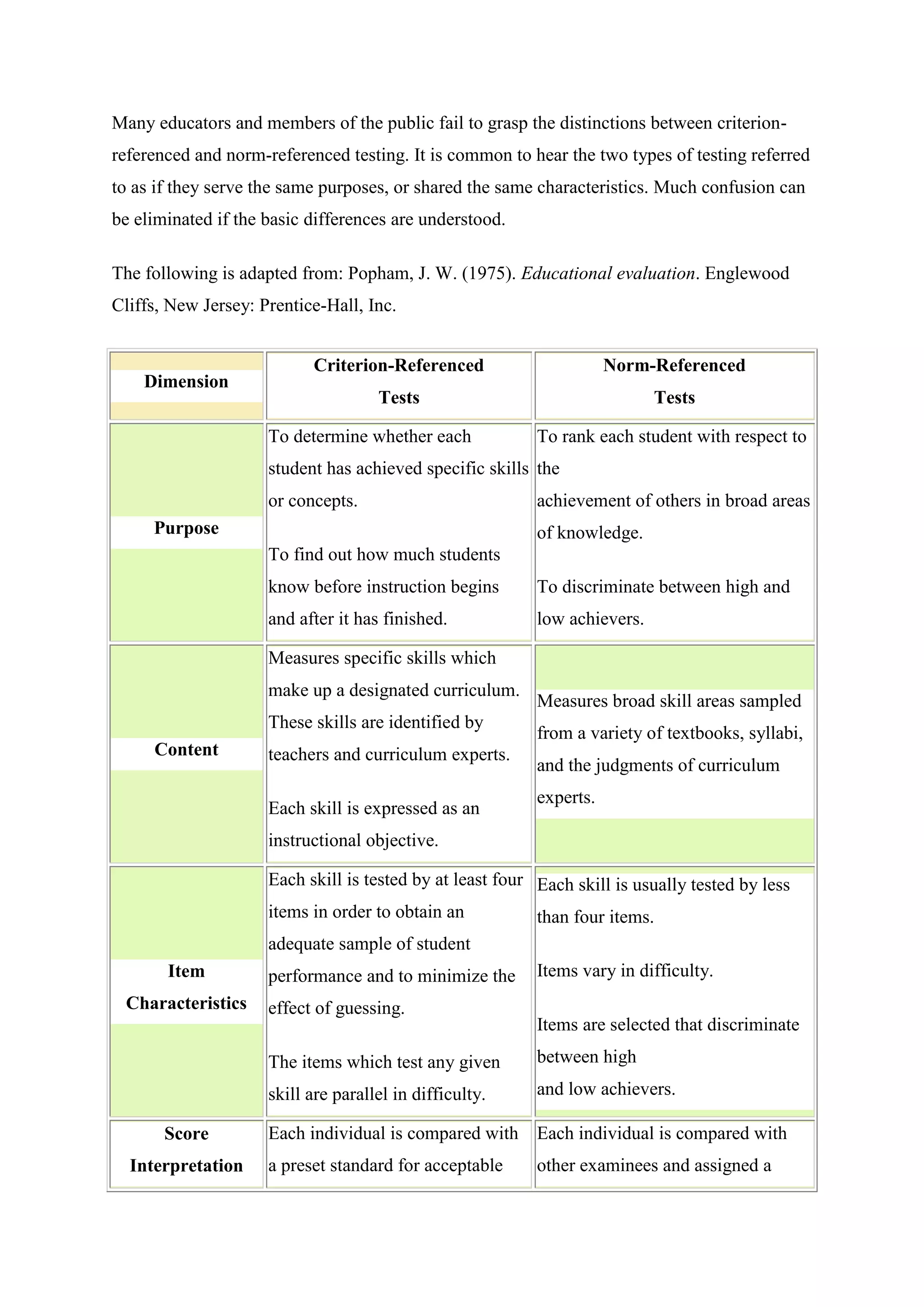

The document discusses the differences between norm-referenced and criterion-referenced testing methods for determining student grades. Norm-referencing involves ranking students and curving grades to fit a predetermined distribution, while criterion-referencing compares student performance to clear standards and outcomes. The document argues that while criterion-referencing is more educationally sound, pure implementations of either approach have limitations, and that in practice, higher education uses a balanced mix of both methods.