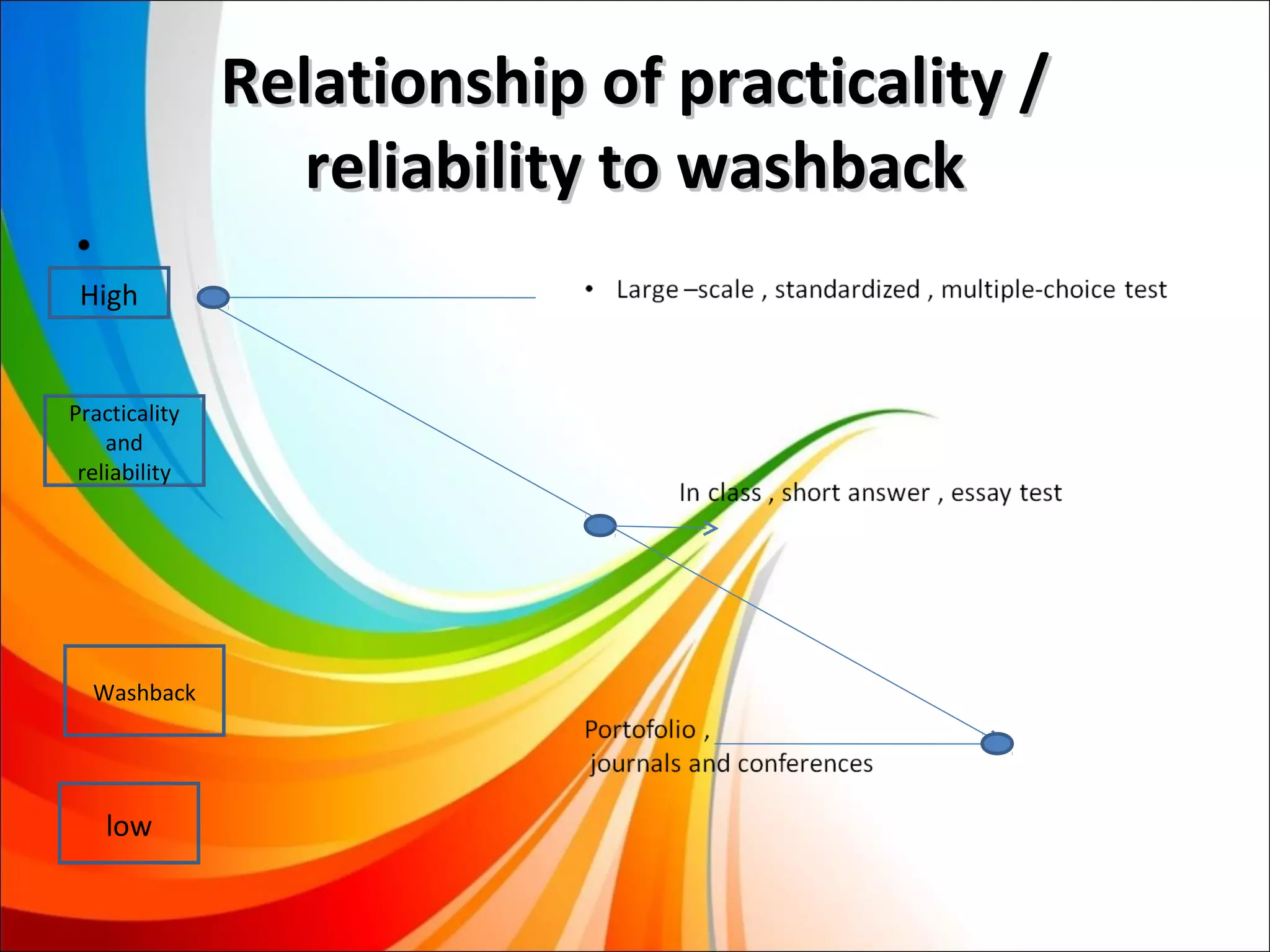

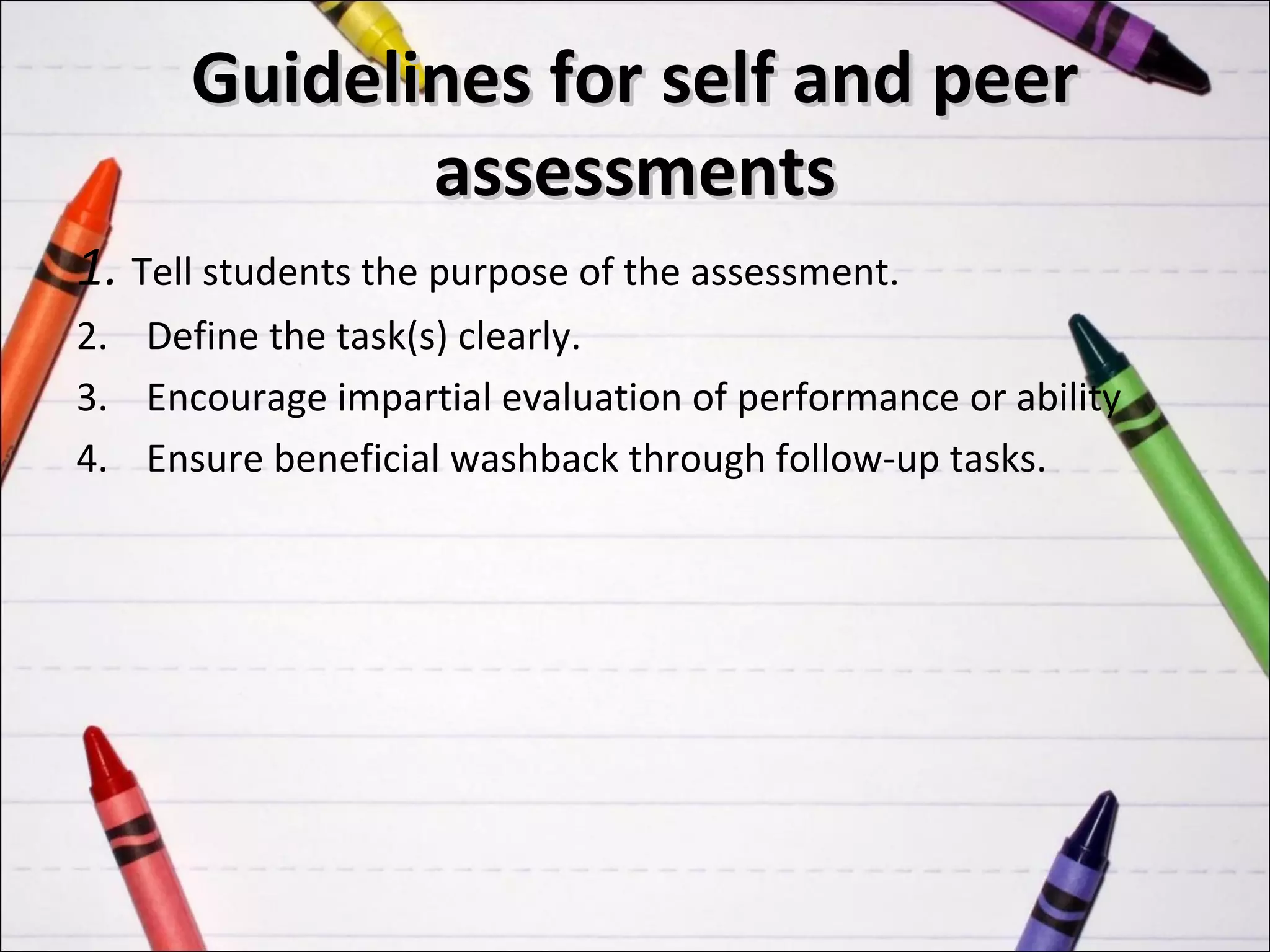

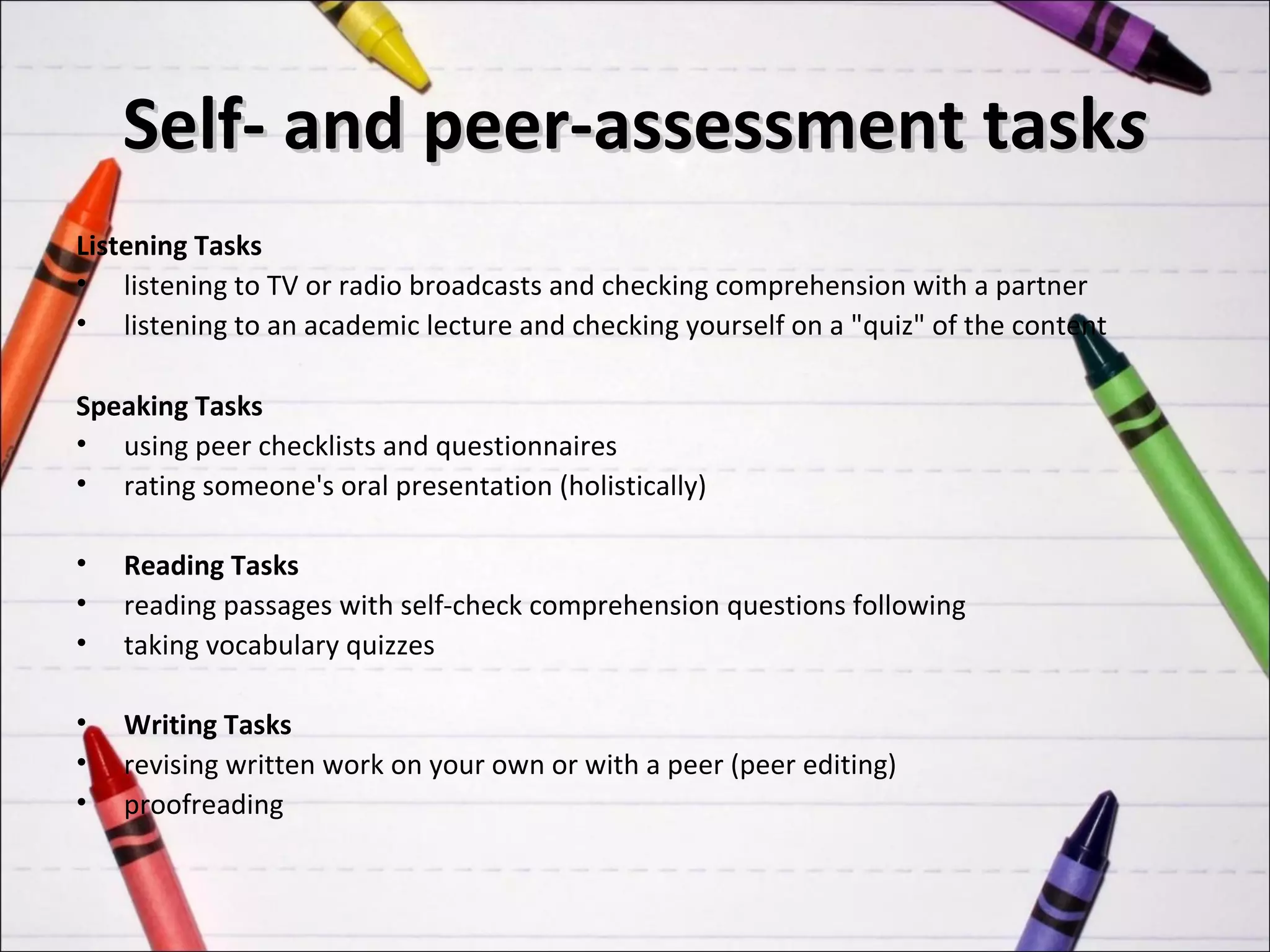

This document discusses alternatives to standardized testing for student assessment, including performance-based assessments, portfolios, journals, conferences, interviews, and observations. It provides characteristics and guidelines for implementing each alternative form of assessment in the classroom. The alternatives allow for a more holistic evaluation of students and more authentic demonstrations of their skills.