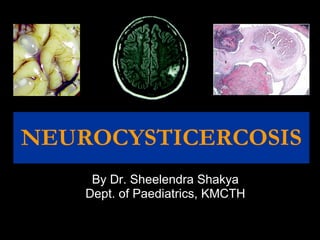

Neurocysticercosis is a disease caused by the larval form of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium infecting the brain and central nervous system in humans. There are two types of cysts - Cysticercus cellulosae and Cysticercus racemose, which can lodge in different areas and cause different symptoms. Neurocysticercosis has a variety of clinical presentations depending on the location, size, and number of cysts as well as the host's immune response. Treatment approaches for neurocysticercosis are controversial, with some evidence that antiparasitic treatment may cause more harm than benefit compared to simply managing seizures with antiepileptic drugs alone.