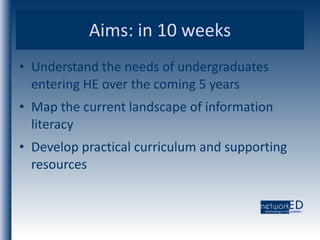

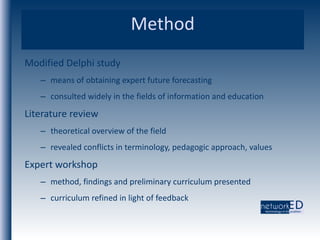

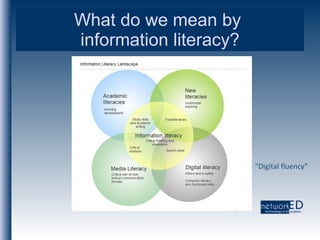

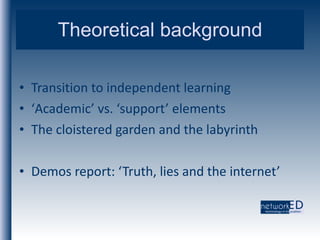

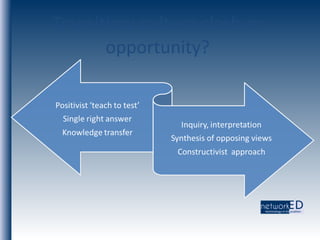

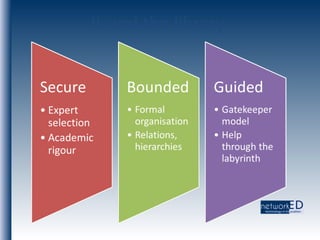

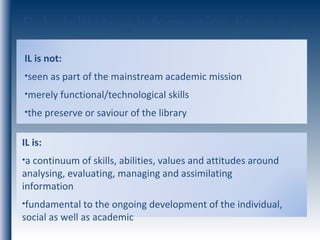

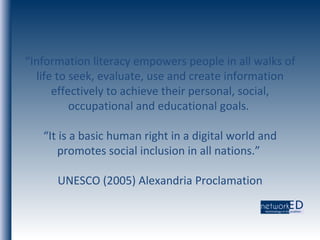

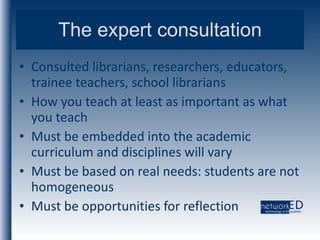

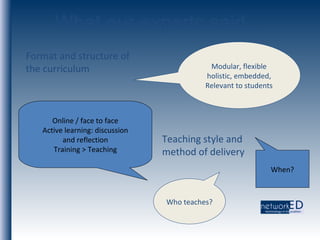

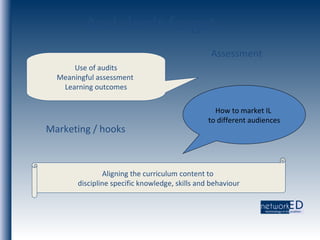

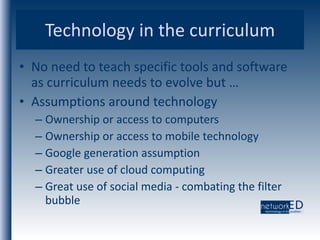

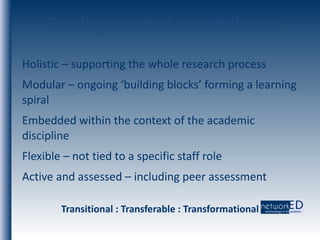

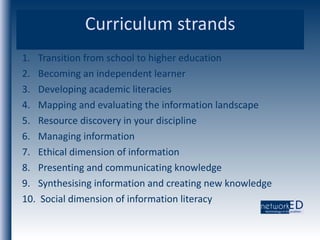

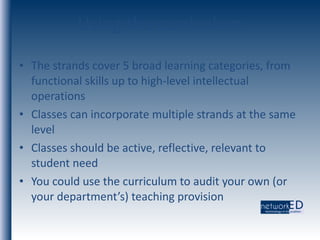

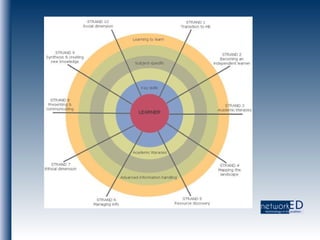

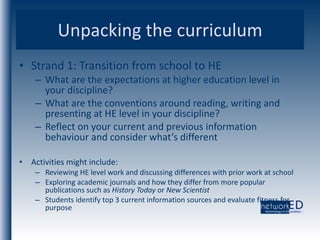

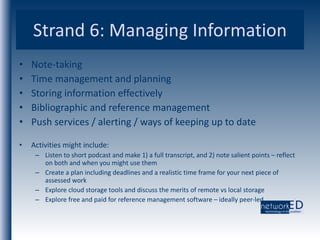

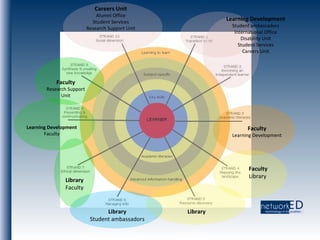

The document summarizes research conducted by Dr Jane Secker and Dr Emma Coonan to develop a new curriculum for information literacy for undergraduates entering higher education over the next 5 years. They conducted a modified Delphi study with experts in information and education fields. Based on the expert consultation, literature review, and theoretical background, they developed a modular and flexible curriculum with 6 strands covering skills from foundational to advanced. The curriculum is intended to be embedded within academic disciplines and address the real needs of students through active and assessed learning opportunities.