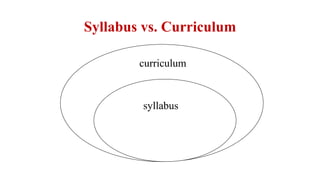

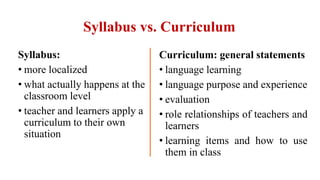

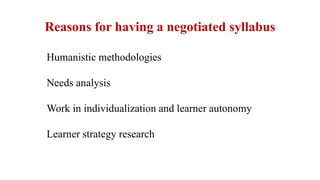

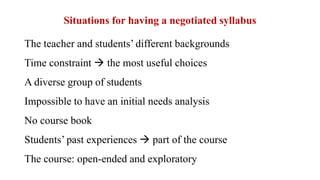

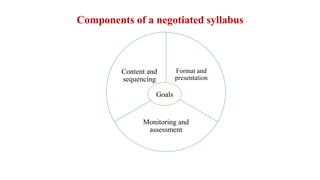

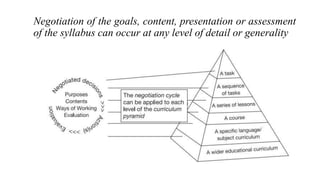

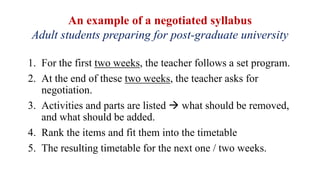

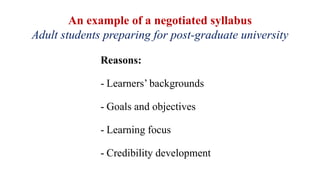

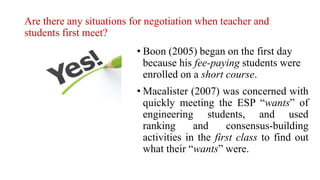

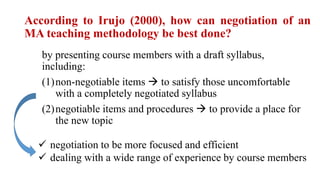

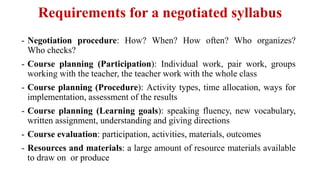

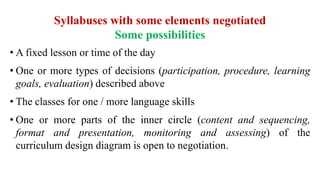

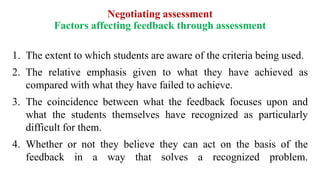

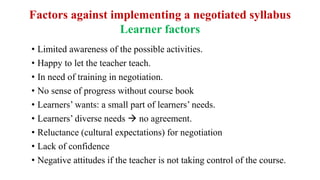

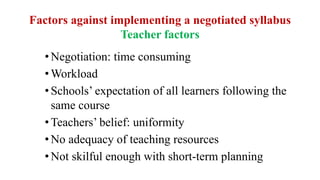

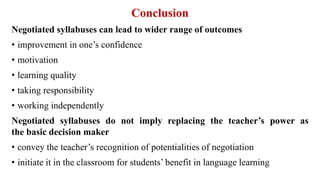

This document discusses negotiated syllabuses, which involve teachers and learners working together to make decisions about course design. It outlines the key components that can be negotiated, including goals, content, presentation, and assessment. The steps for implementing a negotiated syllabus are presented, as well as examples. Both the advantages and disadvantages are examined, such as increased learner involvement but also the time commitment required. Requirements for negotiated syllabuses include establishing procedures for negotiation and planning course elements collectively. Overall, negotiated syllabuses can improve learner outcomes but also require skilled facilitation from teachers.