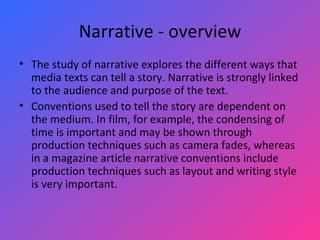

This document discusses several narrative theories, including:

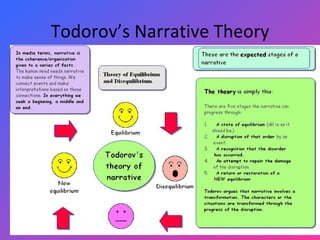

- Todorov's theory that narratives follow an equilibrium-disruption-restoration structure

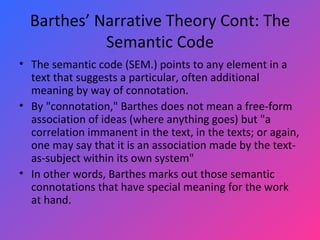

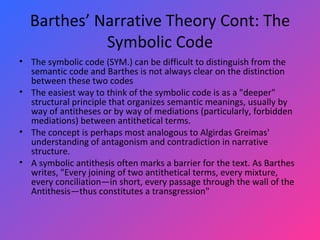

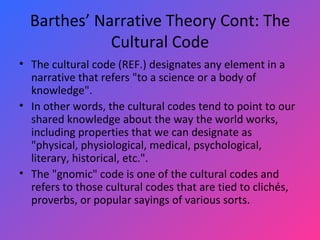

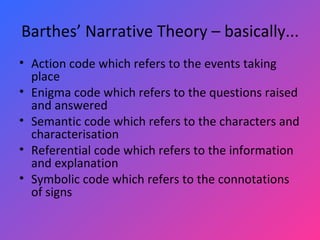

- Barthes' theory that narratives employ codes like hermeneutic (raising questions), proairetic (anticipating actions), semantic, symbolic, and cultural

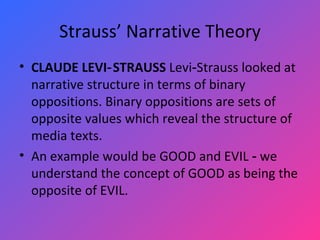

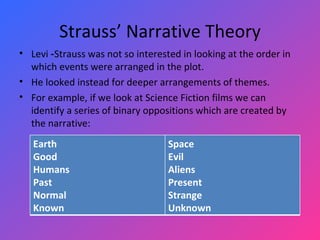

- Levi-Strauss' theory that narratives use binary oppositions like good vs evil

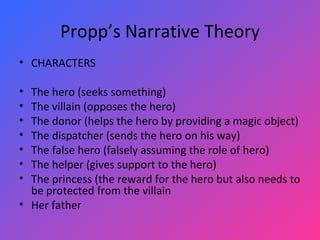

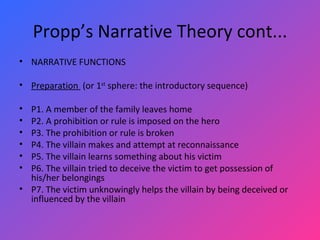

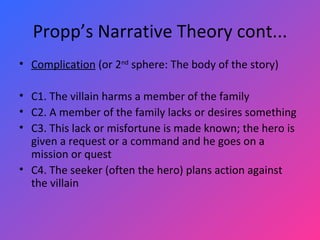

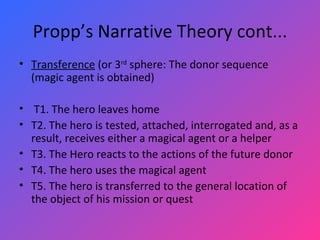

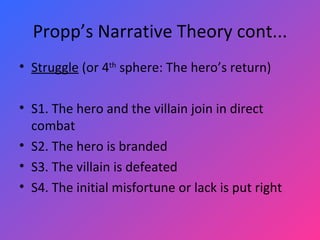

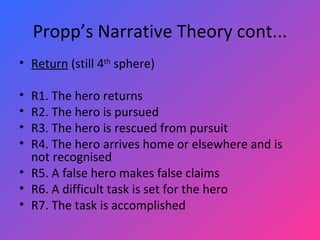

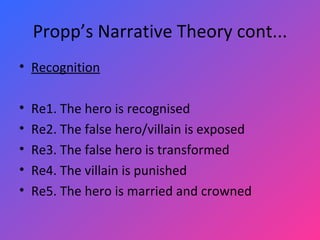

- Propp's analysis identifying character types like hero and villain, and narrative functions like lack, mediation, struggle, and return in folk tales

![Barthes’ Narrative Theory Cont. These first two codes tend to be aligned with temporal order and thus require, for full effect, that you read a book or view a film temporally from beginning to end. A traditional, "readerly" text tends to be especially "dependent on [these] two sequential codes: the revelation of truth and the coordination of the actions represented The next three codes tend to work "outside the constraints of time" and are, therefore, more properly reversible, which is to say that there is no necessary reason to read the instances of these codes in chronological order to make sense of them in the narrative.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/narrativetheory2-111125054703-phpapp01/85/Narrative-theory-2-11-320.jpg)