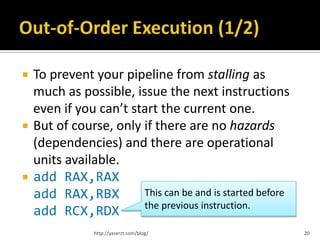

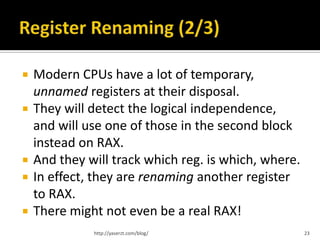

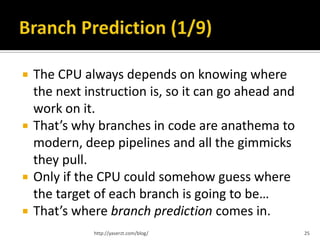

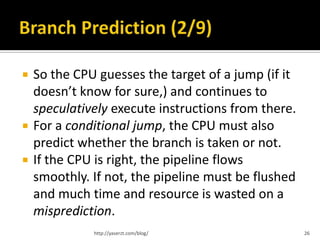

This document summarizes key concepts related to CPU architecture and performance, covering topics such as memory handling, instruction execution, and the evolution of CPUs from the 8086 model to modern multi-core designs. It discusses various techniques used to enhance performance, including pipelining, superscalar architectures, and branch prediction, while also addressing the complexities and limitations of these advancements. The information is intended for those with a foundational understanding of computer architecture, presented with generalizations and simplified explanations.

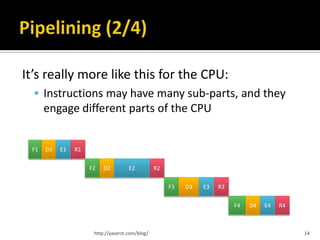

![But it has its own share of problems

Hazards, stalls, flushing, etc.

Execution of i2 depends on the result of i1

After i2, we jump and the i3, i4,… are flushed out

F1 D1 E1 R1 add EAX,120

F2 D2 E2 R2 jmp [EAX]

F3 D3 E3 R3 mov [4*EBX+42],EDX

F4 D4 E4 R4 add ECX,[EAX]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-16-320.jpg)

![ Instructions are broken up into simple,

orthogonal µ-ops

mov EAX,EDX might generate only one µ-op

mov EAX,[EDX] might generate two:

1. µld tmp0,[EDX]

2. µmov EAX,tmp0

add [EAX],EDX probably generates three:

1. µld tmp0,[EAX]

2. µadd tmp0,EDX

3. µst [EAX],tmp0

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-17-320.jpg)

![ This obviously also applies at the µ-op level:

mov RAX,[mem0] Fetching mem1 is started long

mul RAX,42 before the result of the

multiply becomes available.

add RAX,[mem1]

push RAX

Pushing RAX is sub RSP,8 and then

call Func mov [RSP],RAX. Since call

instruction needs RSP too, it will only

wait for the subtraction and not the

store to finish to start.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-21-320.jpg)

![ Consider this:

mov RAX,[mem0]

mul RAX,42

mov [mem1],RAX

mov RAX,[mem2]

add RAX,7

mov [mem3],RAX

Logically, the two parts are totally separate.

However, the use of RAX will stall the pipeline.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-22-320.jpg)

![ This is, for once, simpler than it might seem!

Every time a register is assigned to, a new

temporary register is used in its stead.

Consider this:

Rename happens

mov RAX,[cached]

mov RBX,[uncached]

Renaming on mul means

add RBX,RAX that it won’t clobber RAX

mul RAX,42 (which we need for the

add, that is waiting on the

mov [mem0],RAX load of [uncached]) and we

mov [mem1],RBX can do the multiply and

reach the first store much

sooner.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-24-320.jpg)

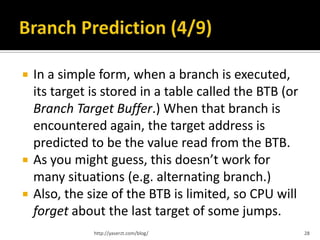

![ In this code:

cmp RAX,0

jne [RBX]

both the target and whether the jump happens

or not must be predicted.

The above can effectively jump anywhere!

But usually branches are closer to this:

cmp RAX,0

jne somewhere_specific

Which can only have two possible targets.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-27-320.jpg)

![mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16

cmp RAX,0

je IsNull

mov [RBX-16],RCX

mov RCX,[RDX+0]

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-34-320.jpg)

![Clock 0 – Instruction 0

mov RAX,[RBX+16] Load RAX from memory

add RBX,16 Assume cache miss – 300

cmp RAX,0 cycles to load

Instruction starts and

je IsNull

dispatch continues...

mov [RBX-16],RCX

mov RCX,[RDX+0]

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-35-320.jpg)

![Clock 0 – Instruction 1

mov RAX,[RBX+16] This instruction writes RBX,

add RBX,16 which conflicts with the

cmp RAX,0 read in instruction 0.

Rename this instance of

je IsNull

RBX and continue…

mov [RBX-16],RCX

mov RCX,[RDX+0]

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-36-320.jpg)

![Clock 0 – Instruction 2

mov RAX,[RBX+16] Value of RAX not available

add RBX,16 yet; cannot calculate value

cmp RAX,0 of Flags reg.

Queue up behind

je IsNull

instruction 0…

mov [RBX-16],RCX

mov RCX,[RDX+0]

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-37-320.jpg)

![Clock 0 – Instruction 3

mov RAX,[RBX+16] Flags reg. still not available.

add RBX,16 Predict that this branch is

cmp RAX,0 not taken.

Assuming 4-wide dispatch,

je IsNull

instruction issue limit is

mov [RBX-16],RCX reached.

mov RCX,[RDX+0]

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-38-320.jpg)

![Clock 1 – Instruction 4

mov RAX,[RBX+16] Store is speculative. Result

add RBX,16 kept in Store Buffer. Also,

cmp RAX,0 RBX might not be available

yet (from instruction 1.)

je IsNull

Load/Store Unit is tied up

mov [RBX-16],RCX from now on; can’t issue

mov RCX,[RDX+0] any more memory ops in

mov RAX,[RAX+8] this cycle.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-39-320.jpg)

![Clock 2 – Instruction 5

mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16

cmp RAX,0 Had to wait for L/S Unit.

je IsNull Assume this is another (and

unrelated) cache miss. We

mov [RBX-16],RCX

have 2 overlapping cache

mov RCX,[RDX+0] misses now.

mov RAX,[RAX+8] L/S Unit is busy again.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-40-320.jpg)

![Clock 3 – Instruction 6

mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16

cmp RAX,0

je IsNull

RAX is not ready yet (300-

mov [RBX-16],RCX

cycle latency, remember?!)

mov RCX,[RDX+0] This load cannot even start

mov RAX,[RAX+8] until instruction 0 is done.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-41-320.jpg)

![Clock 301 – Instruction 2

mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16 At clock 300 (or 301,) RAX is

cmp RAX,0 finally ready.

je IsNull Do the comparison and

update Flags register.

mov [RBX-16],RCX

mov RCX,[RDX+0]

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-42-320.jpg)

![Clock 301 – Instruction 6

mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16

cmp RAX,0

je IsNull Issue this load too. Assume

mov [RBX-16],RCX a cache hit (finally!) Result

mov RCX,[RDX+0] will be available in clock

mov RAX,[RAX+8] 304.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-43-320.jpg)

![Clock 302 – Instruction 3

mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16 Now the Flags reg. is ready.

cmp RAX,0 Check the prediction.

je IsNull Assume prediction was

correct.

mov [RBX-16],RCX

mov RCX,[RDX+0]

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 44](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-44-320.jpg)

![Clock 302 – Instruction 4

mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16

cmp RAX,0

je IsNull This speculative store can

actually be committed to

mov [RBX-16],RCX memory (or cache,

mov RCX,[RDX+0] actually.)

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-45-320.jpg)

![Clock 302 – Instruction 5

mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16

cmp RAX,0

je IsNull

mov [RBX-16],RCX At clock 302, the result of

mov RCX,[RDX+0] this load arrives.

mov RAX,[RAX+8]

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-46-320.jpg)

![Clock 305 – Instruction 6

mov RAX,[RBX+16]

add RBX,16

cmp RAX,0

je IsNull

mov [RBX-16],RCX

mov RCX,[RDX+0] Result arrived at clock 304;

mov RAX,[RAX+8] instruction retired at 305.

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-47-320.jpg)

![To summarize,

mov RAX,[RBX+16] • In 4 clocks, started 7 ops

add RBX,16 and 2 cache misses

cmp RAX,0 • Retired 7 ops in 306 cycles.

• Cache misses totally

je IsNull

dominate performance.

mov [RBX-16],RCX • The only real benefit came

mov RCX,[RDX+0] from being able to have 2

mov RAX,[RAX+8] overlapping cache misses!

http://yaserzt.com/blog/ 48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/igdiworkshop02-yzt-moderncpuandmemory-r02-130105002319-phpapp01/85/Modern-CPUs-and-Caches-A-Starting-Point-for-Programmers-48-320.jpg)