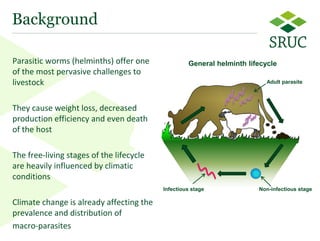

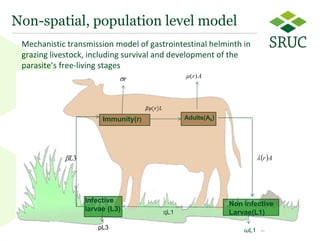

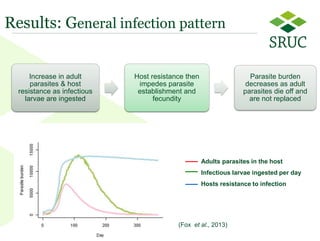

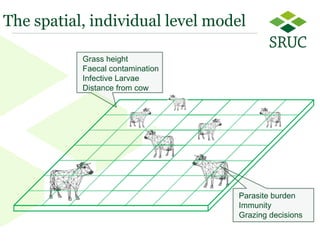

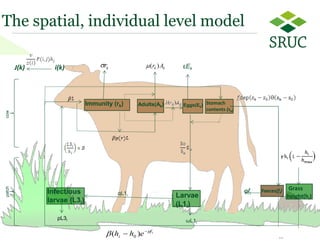

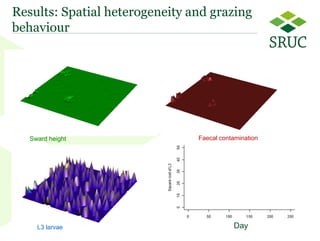

This document summarizes a model developed to understand how climate change may impact parasitic worms (helminths) that infect livestock. The model examines the lifecycle of these parasites, which have free-living stages affected by climate, and infectious stages that infect hosts. The model shows that higher temperatures can increase parasite burden by speeding larval development. Incorporating spatial heterogeneity and grazing behavior into the individual-level model indicates these farm-level processes also influence outbreak intensity under climate change scenarios. The model can be used to predict parasite risk from climate change and assess control strategies.