This document is a thesis presented by Miguel de Vega Rodrigo to obtain a doctorate in engineering sciences from the Université libre de Bruxelles in 2008. The thesis models future all-optical networks without buffering capabilities, specifically optical burst switching (OBS) and optical packet switching (OPS) networks. It covers the functional and hardware implementation of such networks, characterization of internet traffic that will enter these networks, and mathematical modeling approaches for the networks and traffic.

![Introduction

These days, optical networks can be found anywhere from the access level to the

very core of the Internet. But it is in the transmission of large amounts of infor-

mation over long distances that they provide indisputable advantages over other

transport technologies. The following dissertation focuses on such long-distance

optical networks, also referred to as backbone, long-haul or core networks [102].

Most current backbone optical networks are built on two main cornerstones.

First, they are circuit-switching networks. That is to say, user information is sent

between a pair of source-destination nodes as a continuous constant-rate bitstream

that follows the same route or path across the network. Here, a node represents a

point in the network where information can be transmitted, received or forwarded.

Second, their data plane is not all-optical. In other words, the bitstream containing

user information is sent optically through the links of the network, but is converted

to electronic signals at its nodes.

This scenario is not static or permanent. Optical networks are constantly

evolving in an attempt to meet the ever-increasing demand for bandwidth created

by the expansion of the Internet. This expansion has been one of the main catalysts

behind the unprecedented growth of optical networks in the past several years.

However, it has also created a demand for new dynamic and upgradeable optical

networks.

The need for dynamic optical networks is conrmed by many empirical studies

reporting that Internet trac is highly variable and bursty (see for instance [31,

55, 96, 42]). An ecient and natural way of coping with such variable trac is

to use packet-switching optical networks [115]. In such networks, user information](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-15-320.jpg)

![ii

is sent between a pair of source-destination nodes as a series of packets that may

follow dierent routes, where a packet is a nite sequence of bits. Thus, one of the

major trends in the design of future optical networks is to move from the current

circuit-switching to the packet-switching paradigm [138, 83].

The need for upgradeable optical networks arises from the continuously-in-

creasing demand for bandwidth prompted by the expansion of the Internet. An

ecient way of designing an upgradeable network is to make it all-optical - that

is, to use exclusively optical components for the transmission of user information

across the network. Indeed, it is relatively simple to upgrade the data rate in all-

optical networks by adding extra transmission channels [16]. Moreover, all-optical

networks have at least two additional advantages. First, they can potentially

reduce costs by saving on expensive electronics and opto-electro-optic (O/E/O)

converters, and by reducing power consumption. Second, they can eliminate the so-

called electronic bottleneck. This bottleneck is currently one of the major factors

limiting capacity in an optical network. It is a result of the low processing speed of

the electronic equipment at the nodes compared to the high transmission capacity

at the optical links. All these advantages make all-optical networking another

major trend in the design of future optical networks [136, 138, 83, 134, 121].

The two trends mentioned above give rise to the concept of a pure packet-

oriented all-optical network, called an Optical Packet Switching (OPS) network in

the literature [138, 83]. The main objective in the design of an OPS network is to

maximize its performance. Secondary objectives are the cost and feasibility of the

all-optical hardware components needed.

The term performance is somewhat ambiguous. It can refer to the eciency

with which bits are physically represented, transferred and received in a network.

Typical performance parameters in this case are the bit error rate (BER) or the

signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [4]. Performance can also refer to the eciency with

which packets are transferred through the network by the network protocols. Net-

work protocols can delay and sometimes cause the loss of packets. The main

performance parameters in this case are the average packet delay and the packet

blocking probability, which basically refers to the probability that a packet will

be lost in the network. In this dissertation, we are interested in the study of a

packet-switching all-optical network at the packet level of abstraction (i.e., at the

OSI network layer). Thus, the term performance will hereinafter be used in order

to refer to the average packet delay and the packet blocking probability.

In order to maximize the performance of an OPS network, it is customary to

include the following three requirements in its denition [136, 138, 83]. First, not

only the data plane, but also the control plane must be all-optical. That is to

say, signaling information used to manage network bandwidth must be processed

optically. This allows the control plane to prot from the above-mentioned benets](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-16-320.jpg)

![iii

of an all-optical implementation. Second, incoming electronic packets must be sent

on the y (i.e., as they arrive) through the optical domain. This minimizes packet

delay at the ingress nodes in the network. Third, buering must be available at the

optical domain, permitting the reduction of the blocking probability and thereby

increasing network throughput.

The downside of these three requirements is that they notably increase the

complexity associated with the implementation of an OPS network [83]. More

specically, the rst requirement implies the use of extensive signal processing ca-

pabilities at the optical domain, a technology that is not yet mature enough [19].

The second requirement implies that optical packets have the same size as incom-

ing Internet (IP) packets. This sets the operating times of the optical components

in the OPS network (e.g., the switching times) to the ns range [28], represent-

ing a considerable challenge for current technology. The third requirement also

represents a problem, because there is no optical equivalent to the random access

memory (RAM) used to build the buers in electronic packet-switching networks.

The best option available are ber delay lines (FDLs), which are more expensive

and dicult to control than RAMs [44], and increase signal degradation at the

optical domain due to physical system impairments [116].

The fact that OPS networks are so dicult to implement creates room for

alternative networking solutions, where lower performance is accepted in exchange

for a less expensive and complex hardware implementation. One such alternative

solution is Optical Burst Switching (OBS).

The denition of an OBS network strategically avoids the use of the three

requirements presented above, while still remaining faithful to the basic principles

of a packet-switching all-optical network [134, 135]. First, the control plane is

implemented electronically (although the data plane is still all-optical). Second,

incoming electronic packets are buered at the ingress nodes in the network in

order to form large groups of packets called bursts, which are then transferred

through the optical domain. This relaxes the operating time requirements from

the ns to the µs range [67]. Third, as buering is not available at the optical

domain, the use of FDLs is avoided. These characteristics will most probably

enable OBS networks to be implemented earlier and at a lower cost than OPS

networks [121].

Research on OBS networks has been quite extensive in the last decade and

focuses mainly on two questions. The rst question is whether OBS networks can

be deployed soon and in a cost-ecient manner. The second question is whether

OBS networks can provide a clear advantage in terms of performance compared

to current optical network architectures.

This thesis focuses on the second question formulated above. Our main objec-

tive is to provide the research community with a tractable and reliable analytical](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-17-320.jpg)

![iv

network model that can be used in order to assess the performance in OBS net-

works in terms of the burst blocking probability. By tractable we mean a model

from which the blocking probability can be computed within a reasonable time

using a reasonable amount of computational resources. By reliable we mean a

model that includes enough functional and structural details from the original

OBS network in order to be realistic and accurate. The use of our analytical net-

work model to actually evaluate the viability of OBS networks is out of the scope

of this dissertation.

It turns out that the model developed for OBS networks in this thesis can

also be used in order to model OPS networks without buering capabilities (i.e.,

without FDLs), also denoted as buerless OPS networks. These networks are

of great practical importance, since their study can help to decide whether it is

necessary or not to invest resources in the development and use of FDLs for OPS

networks [82, 81].

The blocking probability is the performance parameter of interest in our net-

work model, since neither OBS nor buerless OPS networks have FDLs to reduce

blocking at the core nodes. It has also been the preferred performance parameter

studied in the literature on OPS/OBS networks [167, 99, 167, 66].

The study of other performance parameters falls out of the scope of this doc-

ument. Such is the case of the results published in [40]. In that paper, we present

a new framework to study the problem of planning an OBS network from scratch.

The objective is to ensure that ows in the network meet previously given QoS

(Quality of Service) requirements in the form of maximum average packet delay

and blocking probability.

In this thesis, we develop the analytical network model of a buerless OPS/OBS

network in three steps that we call the Network step, the Trac step and the

Modeling step. In the Network step, the objective is to study the optical network

in detail and to decide which aspects of its functionality and structure should be

included in the network model. In the Trac step, the goal is to study network

trac in detail and to decide which statistical properties should be included in the

network model. In both steps, the main criterium used to select the information

to be included in the network model is an often dicult compromise between its

resulting reliability and mathematical tractability. In the Modeling step, the goal

is to produce the analytical network model based on the modeling considerations

collected in the previous steps, together with the corresponding algorithm for the

computation of the blocking probability.

The three steps mentioned above serve as the backbone for structuring this

work and are reected in the three parts into which this thesis is divided. We

proceed now to explain each part.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-18-320.jpg)

![v

Part I: Networks. This part presents functional and structural details con-

cerning the buerless OPS/OBS network to be modeled here. As stated before,

the main goal is to identify the most important features of a buerless OPS/OBS

network in order to take them into account in the network model developed in

Part III of this thesis. This, and the associated literature survey are the main

contributions from this part.

OPS and OBS networks constitute extremely active research elds. It is there-

fore not surprising that many variants of these networks have been presented and

studied in the literature. Designing a model for a particular variant has the dis-

advantage of reducing its use to just that variant. Designing a model for each one

of the dierent variants constitutes a lengthy task beyond the scope of any single

dissertation. In this work, we have opted for a third possibility and designed a

model for a basic or standard version of an OBS network, the origin of all other

variants. This standard version corresponds to the concept of OBS networking, as

originally introduced by Qiao and Yoo in [134, 135]. The resulting model is also

valid for a standard OPS network as presented in [108], but without FDLs at the

core nodes.

Part I focuses on the description of the above-mentioned standard versions of

a buerless OPS/OBS network. This document does not include the study of any

variants. Such studies can be found in [41] and [131], contributions from which

will be briey summarized here.

OBS core nodes use algorithms called reservation mechanisms in order to re-

serve a portion of bandwidth on a link for the transmission of a burst upon the

arrival of its associated header packet. In [41] we present a new reservation mech-

anism for OBS networks. We show analytically that it performs better than the

best state-of-the-art reservation mechanism in terms of burst blocking probability,

and that it allows for a less complex and cheaper network implementation.

Many authors predict performance problems if an OBS network uses the TCP

(Transmission Control Protocol) as a transport protocol [72, 77, 168, 24, 43].

In [131] we put these results into perspective by reporting that when the num-

ber of TCP end users is high (above 100) and a realistic version such as TCP Reno

is used, performance is not severely aected by the use of TCP in OBS networks.

Part I is divided into two chapters. Chapter 1 provides an introduction to OPS

and OBS networks as a particular type of all-optical network. The main focus is

on a functional or procedural description of their four basic elements: ingress edge

nodes, transmission links, core nodes and egress edge nodes. Essentially, we limit

ourselves to the description of what these elements do in order to transfer user

information through the network, and intentionally skip the details concerning

their structure and hardware implementation. At the end of the chapter, we](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-19-320.jpg)

![vi

identify the most relevant functional features of buerless OPS/OBS networks in

order to take them into account in the network model developed in Part III.

In Chapter 2 we study the hardware implementation of an OBS network. The

main goal is to identify the most important structural features to be considered in

the analytical model in Part III. The idea here is to describe how the basic elements

in an OBS network can be modeled, based on their particular hardware implemen-

tation. A secondary goal is to provide the reader with information concerning the

state-of-the-art techniques for implementing an OBS network.

The hardware implementation of our standard buerless OPS network from [108]

is very similar to that of our standard OBS network from [134, 135]. There are basi-

cally only two main dierences. First, hardware operating times for OPS networks

are at least three orders of magnitude below those for OBS networks [67, 28]. Sec-

ond, OPS networks require the development of new tailor-made optical hardware

for the implementation of the control plane in the optical domain. These dier-

ences play a crucial role in the commercial potential of each one of the networking

solutions. However, from the structural point of view, the hardware implementa-

tion of the data plane in these networks is the same in both cases [16]. For this

reason, structural modeling features from the data plane identied in this chapter

are assumed to be valid for buerless OPS networks as well.

Part II: Trac. This part presents a study of the trac inside a buerless

OPS/OBS network. The main goal is to identify which statistical properties of

this trac should be taken into account in the network model developed in Part

III.

Buerless OPS/OBS networks are not yet commercially available, and thus it

is not possible to directly measure the statistical properties of their trac. In

Part II we overcome this problem by means of a two-step approach. In Chapter 3

we study the statistical properties of the trac that is most likely to arrive at a

buerless OPS/OBS network. In Chapter 4 we deduce from the results of Chapter

3 the statistical properties of trac entering the optical domain in a buerless

OPS/OBS network.

Buerless OPS/OBS networks constitute backbone network solutions and as

such are expected to receive highly-aggregated Internet (or IP) trac at their

ingress nodes [74, 138, 26, 133]. That trac exhibits a high throughput result-

ing from the aggregation of many individual IP ows. Thus, it is possible to

study current highly-aggregated trac from the Internet backbone and assume

that similar trac will arrive at future buerless OPS/OBS networks. Accordingly,

our main goal in Chapter 3 is to gain insight on the statistical nature of highly-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-20-320.jpg)

![vii

aggregated IP trac as representative of the trac entering a typical buerless

OPS/OBS network. Previous studies report contradictory results on this matter.

On the one hand, some authors have reported the existence of long-memory or

long-range dependent (LRD) properties in low-aggregated [107, 35] as well as in

highly-aggregated IP trac [126]. On the other hand, papers such as [22, 23, 96]

acknowledge the existence of LRD in low-aggregated IP trac, but report that

as the level of aggregation increases, LRD disappears and trac progressively re-

sembles a Poisson process. Perhaps inspired by this conclusion, the majority of

publications in the eld of backbone optical networks use models with Poisson

trac (see for instance [80, 46, 141]).

Theoretically, in order to settle the debate on the statistical nature of highly-

aggregated IP trac, one could simply perform a statistical analysis of network

trac in a high-capacity optical backbone link. In practice, two main diculties

arise when trying to accomplish such a task. First, due to condentiality issues, it

is dicult for the research community to access such information, owned in most

cases by private network operators. Second, the ecient measurement of trac at

Gbps speeds is a very challenging technical task. Hardware limitations often reduce

the precision of the packet time-stamps to µs, as in [96]. Software limitations have

an impact on the amount of data that can be analyzed and therefore often reduce

the signicance of the results obtained.

Our contribution to this debate is a detailed statistical analysis of a set of two

trac traces provided by the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) within

the framework of the European-funded research projects NOBEL I and NOBEL

II [132]. These traces contain an unprecedent amount of accurate data taken

from a highly-aggregated transmission link. More specically, each trace contains

approximately 800 million packet arrival time and packet size measurements from

a 2-Gbps link, where packet arrival times are measured with ns-precision.

Our main result is a rejection of the Poisson hypothesis and strong evidence

suggesting the presence of LRD in all the traces analyzed. This result is important,

since it is widely known that LRD has a signicant negative impact on network

performance, measured in terms of such parameters as the buer dynamics and

blocking probability [126, 63].

We conducted additional studies in order to determine scaling properties in the

trac beyond LRD. In particular, in [42, 21] we studied the multifractal proper-

ties of trac (see [55]) by means of the Multiscale Diagram presented in [2, 164].

However, we do not include these results in the dissertation for two reasons. First,

in [164] the authors express their reservations about the eectiveness of the Multi-

scale Diagram and other standard tests for detecting the presence of multifractal

behavior. Second, even if it could be eectively detected, it is not clear that

multifractal trac has a substantial impact on network performance [9].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-21-320.jpg)

![viii

In Chapter 4, we assume the existence of LRD IP trac arriving at the ingress

edge nodes in an OPS/OBS network (in line with the evidence reported in Chapter

3) and study if and how LRD is transferred to the departure trac from these

nodes. That is, we study whether LRD is injected into the optical domain in

OPS/OBS networks. As mentioned before, this question is relevant because of the

impact that LRD trac has on network performance.

In OPS networks, the answer to this question is immediately evident. In these

networks, incoming IP packets are sent directly through the optical domain as

they arrive at the ingress edge nodes. An immediate implication of this is that

the statistical properties of incoming IP trac are not modied by the ingress

edge nodes in the OPS network. Thus, we conclude that LRD should be taken

into account in the network model of Part III of this thesis, whenever it is used to

model a buerless OPS network.

In the case of OBS networks the situation is more complex. Indeed, the char-

acteristics of trac entering the optical domain in an OBS network are generally

dierent from those of the incoming electronic trac, due to the fact that incom-

ing IP packets are buered at the ingress nodes to form bursts. In OBS networks,

buering is controlled by an algorithm called the aggregation strategy (AS). The

AS basically decides how many incoming packets should be buered in order to

create a burst. Thus, the question of whether the burst trac entering the OBS

network inherits the LRD from the electronic input trac is dependent on the

choice of the AS.

There are four main ASs presented in the literature: the Timeout, Buer Limit,

Packet Count and Mixed ASs [179, 69, 39, 172].

The impact of the Timeout AS on the degree of LRD of the burst trac entering

an OBS network has been studied in [69, 86, 179, 8, 78, 153]. The methodology

followed in [69, 8, 78, 153] is the use of simulation techniques together with dierent

Hurst parameter estimators to measure the degree of LRD. In [86, 179], several

analytical approximations and asymptotic bounds are obtained. Except for some

discrepancies (see [179, 78]), the general conclusion is that LRD does not seem to

be substantially reduced by the buering that takes place at ingress OBS nodes

using the Timeout AS.

There do not appear to be any equivalent studies in the literature for the other

three ASs, and thus the state-of-the-art picture of trac entering an OBS network

is incomplete. In Chapter 4, we complete this picture by extending the study to

the Packet Count, Buer Limit and Mixed ASs. Our methodology includes both

analytical and simulation studies. From the theoretical point of view, our main

contribution is a new analytical approach based on the discrete wavelet transform

(DWT) to study the presence of LRD in the burst trac entering an OBS network.

In the case of the Packet Count AS, our approach provides exact results, which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-22-320.jpg)

![ix

contrasts with the fact that until now only approximate results had been obtained

for the Timeout AS in [86, 179]. In the case of the Buer Limit AS, our approach

provides approximate results.

The analytical and simulative results from this chapter all suggest that LRD

is neither eliminated nor modied (i.e., the Hurst parameter does not change)

by the main four ASs in an OBS network. Therefore, our main conclusion from

Part II is that LRD should be taken into account when modeling burst trac

entering a buerless OPS/OBS network. This conclusion questions the common

practice of using the Poisson trac assumption in models of backbone optical

networks [80, 46, 141].

Part III: Modeling. This part presents the main results of this dissertation:

a new model of a buerless OPS/OBS network together with an algorithm for

the computation of the blocking probability at any point in the network. As was

explained earlier in this introduction, our goal is to obtain a model that is both

reliable and tractable. In order for the model to be reliable, it should incorporate

the most important features from Part I concerning the functionality and structure

of a typical buerless OPS/OBS network, as well as those from Part II concerning

the statistical properties of its trac. In order for the model to be tractable,

the algorithm for computing the blocking probability should converge within a

reasonable time using a reasonable amount of computational resources.

Chapter 5 presents a preliminary model of a buerless OPS/OBS network and

shows how to compute the blocking probability at any point in it. The preliminary

model includes all the modeling features from Part I, but does not take into account

the result from Part II concerning the LRD nature of burst trac entering a

buerless OPS/OBS network. Instead, the main assumption in this chapter is

that packets/bursts enter the optical domain (i.e., leave the ingress edge nodes)

according to a Poisson process.

Although the assumption above goes against our ndings in Part II the resulting

model is by no means immediately evident, due to the fact that buerless packet-

switching networks exhibit complex behavior. In such networks, packets from a

source interact on each link with packets from other sources routed through that

link. The physical origin of this interaction is the loss of packets (i.e., blocking)

caused by the fact that packets from dierent sources must share a nite number

of transmission channels on each link. As a result of packet loss, the characteristics

of a trac source change whenever it is routed on a link together with other trac.

Therefore, a complete description of the trac on each link in the network requires

full knowledge of the changes accumulated as packets from each source share links

along their path with packets from other sources.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-23-320.jpg)

![x

Previous models of buerless packet-switching networks, such as [46, 45, 173,

5, 141, 167, 163, 159], do not provide a complete description (in the sense given

above) of the trac on each link in the network for two reasons. First, in these

models, packets are assumed to arrive at each node in the network according to the

same type of process (e.g., a Poisson process). That is to say, the packet arrival

process is re-sampled at each node in the network. Second, in these models, packet

transmission times (and therefore packet sizes) are assumed to be re-sampled at

each node in the network (e.g., from an exponential distribution). Re-sampling

of these two stochastic processes (sometimes referred to as link blocking indepen-

dence [163]) inevitably implies the loss of information concerning the blocking

events of packets along the routes in the network, which makes the description of

trac incomplete.

The most outstanding feature of our model is the fact that, to our knowledge,

it incorporates for the rst time a complete description (in the sense given above)

of the trac on each link in the network.

Our model belongs to the class of reversible Markov process models described

in [144], and it is related to well-known stochastic network models used in circuit-

switching networking scenarios, such as [129, 29, 104, 103]. The main dierence

is that in these circuit-switching models there is just one so-called multivariate

birth-death (BD) process to describe trac in the whole network, while in our

case we have a dierent one to describe the trac on each link in the network.

Regarding the computation of the blocking probability in our model, we show

in this chapter that it all comes down to the computation of the well-known par-

tition function [144, 129, 29, 104, 103]. This function has been studied over the

last two decades within the framework of many models of circuit-switching net-

works. In [109] it was demonstrated that its exact computation constitutes a P-

complete problem, where the class P-complete is a subset of the NP-complete

problems. According to current notions in complexity theory, it is widely believed

that no polynomial-time algorithm exists to solve any problem that belongs to the

NP-complete class [64]. This suggests serious scalability problems aecting the

computation of the blocking probability in our model as the size of the network

grows. In the case of the circuit-switching models presented above, such scalability

problems have been solved with the use of Monte Carlo simulation techniques [62].

These techniques provide an estimation of the value of the partition function and

thus of the blocking probability. Since their complexity does not depend on the

size of the network, they do not present any scalability issues. In Chapter 5 we use

a numerical example to demonstrate that the use of Monte Carlo simulation tech-

niques from [104, 103] leads to an accurate estimation of the blocking probability

at dierent points in our network. This allows us to conclude that our model is

tractable, since the blocking probability can be accurately estimated, even in large](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-24-320.jpg)

![xi

OPS/OBS scenarios.

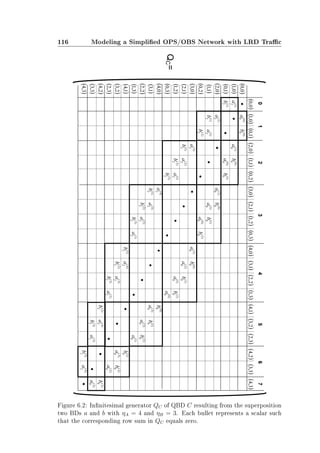

In Chapter 6, we present an intermediate step towards the goal of computing the

blocking probability at any point in a preliminary network model from Chapter

5, upgraded with LRD trac. More specically, we do consider the model from

Chapter 5 upgraded with LRD trac, but we do not seek to compute the block-

ing probability at arbitrary points in the network. Instead, we address the less

ambitious problem of computing the blocking probability at a specic point in the

network. This point is chosen so that the problem is equivalent to the computation

of the blocking probability in a queueing system with a single multi-server node

receiving packets from a LRD trac source and with no buering capabilities.

LRD is a complex phenomenon that involves the presence of specic properties

in network trac over an innite span of timescales. Thus, it comes as no surprise

that the exact computation of performance measures in queuing systems that use

pure LRD packet arrival processes such as fractional Gaussian noise (fGn), remains

analytically untractable for the time being [70, 122, 123].

In order to overcome this problem, it is customary to use what one might call

a pseudo-LRD process (pLRD in short). A pLRD process emulates or mimics to a

certain extent the scale invariance structure typical of a true LRD process. In spite

of this simplication, the exact computation of performance measures in queuing

systems using pLRD packet arrival processes is in some cases also not tractable

using current techniques. This is the case of the B-MWM process introduced

in [140, 63], for instance.

Markov-modulated Poisson processes (MMPPs) constitute a particular class

of Markovian point processes [105]. They are adequate for analytical studies like

ours, since they usually lead to closed-form expressions for the exact computation

of performance measures of interest in a large variety of queuing systems. In the

literature, several pLRD processes based on MMPPs have been presented. Many

of them consist of the superposition of a nite number of independent MMPPs

modeling the behavior at dierent timescales typical of a LRD process. An example

of this can be found in [7, 176, 70, 120]. These processes provide a conceptually

simple, elegant and accurate way of mimicking LRD. For these reasons, we use

them to model LRD in the remainder of this dissertation, and refer to them using

the term Markovian pLRD processes.

Accordingly, the problem addressed in Chapter 6 is equivalent to the compu-

tation of the blocking probability in a MMPP/PH/W/W queuing system (see

Kendalls notation in [101]), where MMPP stands for the Markovian pLRD pro-

cess, PH stands for phase-type distributed service times [105], and W is a nite in-

teger representing the number of servers in the node. The choice for PH-distributed

service times is motivated by the ability of PH distributions to mimic a wide va-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-25-320.jpg)

![xii

riety of distributions, like for instance heavy-tailed distributions [57]. We show in

this chapter that standard matrix analytic methods solve this problem with a com-

plexity that increases exponentially with the number N of independent MMPPs

superposed. According to our numerical experiments, accurate approximations

of LRD processes require N to take large values, which suggests the presence of

scalability problems when using the standard solution.

The main contribution in Chapter 6 is a new algorithm to compute the block-

ing probability in a MMPP/PH/W/W queuing system, when the MMPP is a

Markovian pLRD process. This algorithm exhibits a complexity that scales linearly

with N, and thus does not suer from the above-mentioned scalability problems.

This allows for the use of Markovian pLRD processes with high values of N, in

order to accurately approximate the behavior of real LRD trac.

Our algorithm provides exact results under the assumption that some related

processes exhibit a property called reversibility [144]. We present in this chapter

a Markovian pLRD process, based on the results from [70]. This process does not

fulll the reversibility assumption, and thus our algorithm is in this case regarded

as approximative. We show with a numerical example that our algorithm approx-

imates the blocking probability very accurately. We oer a possible explanation

based on the observation that with this Markovian pLRD process, the reversibility

assumption is close to being fullled.

In Chapter 7 we study the problem of computing the blocking probability at

any point in the network model from Chapter 5, upgraded with Markovian pLRD

processes. That is to say, we address the problem of computing the blocking

probability in a network model of a buerless OPS/OBS network with LRD trac.

We shall call this the LRD Network Problem (in short LRD-NP).

To our knowledge, the network model from the LRD-NP has not been pre-

viously studied in the literature. Perhaps the closest model is the one recently

presented in [163], since it does not make the usual assumption of Poisson traf-

c. Instead, this paper considers an ON-OFF trac model with exponentially

distributed ON and OFF periods. Besides this rather weak connection, the model

in [163] diers fundamentally from our model, since, as previously stated in this

introduction, it is not complete.

In this chapter, the blocking probability in the LRD-NP is computed according

to two dierent methods. The rst one uses standard matrix analytic methods

such as the linear level reduction algorithm from [105, 68]. The second method

constitutes the main contribution from this chapter. It uses the algorithm derived

in Chapter 6 in order to reduce the complexity associated with the computation

of the blocking probability.

Comparing the complexity of the two methods, we conclude that the complexity](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-26-320.jpg)

![Chapter 1

Functional Description of a Buerless

OPS/OBS Network

This chapter presents a general functional description of a buerless OPS/OBS

network. Our main objective is to identify the most important functional fea-

tures of these networks in order to take them into account in the network model

developed in Part III.

The chapter is structured as follows. In Section 1.1 we introduce all-optical

networks as a subclass of telecommunication networks. Sections 1.2 and 1.3 present

a general functional description of an OBS and an OPS network, respectively. In

Section 1.4 we identify the most important functional features from these networks

in order to include them in the network model from Part III.

1.1 All-Optical Networks

In this section we begin with a general denition of a telecommunication network

and then describe the main characteristics which identify all-optical networks as

a subclass of telecommunication networks. Most of the material in this section is

taken from [156].

A telecommunication network is a network of links and nodes arranged so that

information can be passed from one part of the network to another over multiple

links and through various nodes. Telecommunication networks are complex objects

which can be studied under many dierent approaches. Throughout this work we

use mainly two approaches, which we now proceed to describe.

The rst approach divides a telecommunication network in three dierent](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-31-320.jpg)

![4 Functional Description of a Buerless OPS/OBS Network

planes: the data, control and management planes. The data plane (also referred

to as user plane or transport plane) comprises the network components responsi-

ble for carrying the information generated by the users across the network. User

information is called in this context user trac. The transmission of user trac

requires the use of bandwidth resources from the links in the network, which is

controlled by the exchange of signaling information among the dierent network

nodes. The network components responsible for generating, carrying and process-

ing signaling information form the control plane. Finally, the management plane

is formed by the network components in charge of generating, carrying and pro-

cessing administrative information required for network management. A typical

function provided by the management plane is accounting, that is, the processing

and distribution of billing information.

According to this approach, an all-optical network (also called transparent net-

work in the literature) is dened as a telecommunication network of which data

plane is entirely implemented in the optical domain [135]. That is, user trac is

strictly carried by optical signals without conversion to the electrical domain. Note

that this denition does not mention anything about the control and management

planes in all-optical networks, which may use electronic components.

The second approach studies telecommunication networks with the help of

reference models. A reference model interprets a network as a hierarchy of several

layers. Each layer solves a series of problems and provides services to the layer

immediately on top. The problems solved by lower layers are related to the way in

which information is physically conveyed from one point of the network to another.

The problems solved by upper layers are related to the way in which information is

presented to network users. The services provided by each layer to its upper layer

are implemented through a series of methods or algorithms called protocols. The

dierent protocol choices made at each layer result in dierent telecommunication

networks (e.g., satellite, mobile or optical networks).

In this thesis we use the hybrid reference model from [156], which represents a

mixture of the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) and TCP/IP (Transmission

Control Protocol/ Internet Protocol) reference models. The main reason for pre-

senting one model instead of two is simplicity. There is also a number of technical

reasons justifying this choice, and we refer the interested reader to [156, Chapter

1] for details.

The hybrid model is composed of ve layers, which we describe from the bottom

to the top. The physical layer is concerned with the transmission of raw bits

over a link. The design issues here largely deal with the physical transmission

medium over which the bits are sent (e.g. the optical ber). The main task of

the data link layer is to take a raw link and transform it into a link that appears

free of undetected transmission errors to the network layer. The network layer](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-32-320.jpg)

![1.2 Optical Burst Switching Networks 5

is concerned with the transmission of packets between source and destination,

possibly over several links. The basic function of the transport layer is to accept

data from the application layer, split it up into smaller units if needed, pass these

to the network layer, and possibly ensure that the pieces all arrive correctly at

the other end. The application layer contains a variety of protocols which oer a

common interface to the network services to the dierent types of user applications.

In all-optical networks, the protocols implemented in the lowest three layers are

tightly connected to the optical technology used to implement these networks [135,

67]. This is usually not the case for protocols at the transport and application

layers [147, 14]. For this reason, a necessary requirement for a telecommunication

network to be considered all-optical is that its three lowest layers use exclusively

optical technology for the transmission of user trac from the data plane.

All-optical networks may be connected to a wide variety of electronic networks

that typically use ATM (Asynchronous Transfer Mode), Ethernet and/or IP tech-

nology. Trac from electronic IP networks dominates by far the proportion of

total trac injected into current optical networks. This trend is expected to con-

tinue in future all-optical networks due to the increasing demand for bandwidth

of Internet applications [31, 56]. For this reason, throughout this work all-optical

networks are assumed to be connected to electronic IP networks exclusively. In

this thesis we use hereinafter the term IP network in order to refer to an elec-

tronic IP network. The optical version of an IP network is basically what we call

an OPS network.

All-optical networks may use a circuit-switching or a packet-switching para-

digm [115]. Optical circuit switching (OCS) networks constitute the most impor-

tant type of circuit-switching all-optical network [46]. Sometimes they also referred

to as an OFS (Optical Flow Switching) [171] and a WROBS (Wavelength Routed

OBS) networks [52, 169, 50, 51, 49]. The two most relevant types of all-optical

packet-switching networks are OPS [83] and OBS networks [134, 121].

As stated in the introduction of this thesis, we are interested in OBS networks,

as well as in OPS networks without buering capabilities at the core nodes. We

proceed now to describe these networks in more detail.

1.2 Optical Burst Switching Networks

An OBS network can be basically dened as an all-optical packet-switching net-

work with a switching granularity of a burst, where a burst is a collection of IP

packets with the same destination in the OBS network. The basic elements in

an OBS network are four: ingress edge nodes, transmission links, core nodes and

egress edge nodes [46]. In this section we describe how these elements interact in

order to convey user information from one point to another in a standard OBS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-33-320.jpg)

![6 Functional Description of a Buerless OPS/OBS Network

Figure 1.1: OBS Network. Courtesy of Siemens AG.

network. This standard network corresponds to the concept of OBS networking,

as originally introduced by Qiao and Yoo in [134, 135]. We distinguish between

actions that take place within the data plane and within the control plane.

We begin with a functional description of the data plane. Figure 1.1 presents

a typical OBS network with its four basic elements. Incoming IP packets arrive

at an OBS ingress edge node from the electronic domain (see 1 in Figure 1.1). At

the ingress edge node they are sorted according to their destination in the OBS

network and sent to a series of buers, one for each possible destination. Each

buer is controlled by an algorithm called the aggregation strategy (AS). The AS

decides when the aggregation of IP packets in the buer should stop, in which

case the contents of the buer constitute what we call a burst. The ingress edge

node then converts the burst from the electronic to the optical domain and sends

it through the outgoing transmission link connected to the ingress edge node (see

2 in Figure 1.1). Once this operation takes place the burst remains in the optical

domain until it reaches its corresponding egress edge node (see 3, 4 and 5 in

Figure 1.1). More specically, the burst is optically switched at each core node

from its incoming to its corresponding outgoing transmission link. At the egress

edge node the burst is converted from the optical to the electrical domain. Once

in the electrical domain the burst is processed and the corresponding IP packets

are retrieved (see 6 in Figure 1.1).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-34-320.jpg)

![1.3 Optical Packet Switching Networks 7

Transmission links comprise a nite number of independent transmission chan-

nels called wavelength channels. Blocking takes place at a core node when an

arriving burst nds all the wavelength channels in its corresponding outgoing trans-

mission link busy with the transmission of other bursts (see 7 in Figure 1.1). In

this case the IP packets inside the blocked burst are lost.

We proceed now with a functional description of the OBS control plane. The

purpose of this plane is to ensure that each burst arrives at its corresponding egress

edge node, provided that no blocking takes place along its route. This is achieved

by properly managing the bandwidth resources available at the transmission links

in the network through the exchange of signaling information among the dierent

nodes in the network. In OBS networks such signaling information is transferred in

packets called headers (see Figure 1.1). A header is sent prior to the transmission

of each burst (see 3,4 and 5 in Figure 1.1) through a separate control wavelength

channel (detail not shown in the gure) on the same optical ber. Each header and

its associated burst follow the same path across the network. The header contains

the necessary information in order to allocate bandwidth at each core node for the

transmission of its associated burst over the next transmission link or hop. At each

core node the header is converted to the electronic domain, processed by the core

node and then converted back to the optical domain for its transmission through

the next hop. The conversion of headers to the electronic domain at every core

node is what prevents the OBS data plane from being all-optical (see Section 1.1).

The time between the transmission of a header and of its associated burst is called

the oset time (see Figure 1.1). The purpose of the oset time is to provide OBS

core nodes with enough time to recongure themselves before the arrival of the

burst.

1.3 Optical Packet Switching Networks

OPS networks can be basically dened as all-optical packet-switching networks

with the nest switching granularity possible, i.e., that of an IP packet. The basic

elements in an OPS network are the same as in the OBS network (see Section 1.2).

In this section we describe how these elements interact in order to convey user

information from one point to another in a standard OPS network, as dened

in [108]. Like in the previous section, we distinguish between actions that take

place within the data and the control plane (see Section 1.1), and focus on the

dierences compared to the OBS case.

We begin with a functional description of the data plane. The main dierences

compared to the OBS case are two. First, in OPS networks no buering of IP

packets takes place at the ingress edge nodes. That is, IP packets are converted

to the optical domain and sent through the network as they arrive at the ingress](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-35-320.jpg)

![8 Functional Description of a Buerless OPS/OBS Network

edge nodes. Second, OPS networks use FDLs in order to buer packets and reduce

the blocking probability. Thus, if a packet nds all the wavelength channels in its

corresponding outgoing transmission link busy, it is not necessarily blocked or lost

since it may enter an FDL.

Regarding the control plane, the main dierence is that in OPS networks it is

usually assumed to be all-optical [75, 138, 136, 83]. In this case header processing

can be done much faster and there is no need to keep an oset time between the

transmission of the header and its associated packet [19].

1.4 Modeling Considerations

In this section we identify the most important functional features of buerless

OPS/OBS networks in order to take them into account in the network model

developed in Part III. We are still not in a position to see why the same model

in Part III can be used with both, OBS and buerless OPS networks. Thus, for

the moment we just assume that this is the case and wait until Section 4.7 for a

proper explanation.

If a reliable protocol is used at the transport layer, a copy of each IP packet lost

in a blocking event is retransmitted again through the network. An example of such

reliable protocol is TCP. However, even reliable transport layer protocols cannot

immunize the network against the negative eects of blocking [72, 77, 168, 24, 43].

Every packet blocked at the network layer implies some delay needed for the trans-

port protocol to detect its loss and begin its retransmission, and increased network

trac due to the transmission of the copy of the packet. Increasing network traf-

c makes blocking events even more likely to occur. Thus, if many packets are

blocked at the network layer the whole network may get saturated with original

packets and their copies to the extent in which it is incapable of delivering packets

to their destination. This situation is known as network congestion [156]. For

these reasons, the analytical model presented in Part III studies the blocking phe-

nomenon at the network layer where it originates, and ignores the retransmission

eects from a possible reliable transport layer protocol.

Headers are very small compared to the packets/bursts in a buerless OPS/OBS

network. For this reason it is customary to assume that headers are not blocked

and therefore that the OPS/OBS control plane does not have any impact on net-

work performance (see for instance [27, 99, 46, 167, 82]). According to this, the

analytical model presented in Part III focuses on the transmission of packets/bursts

in the data plane and ignores the eects from the control plane.

Routing algorithms in OPS/OBS networks must be extremely fast at comput-

ing the routes due to the short transmission times of packets/bursts over high-

capacity wavelength channels. Therefore, the conventional hop-by-hop IP routing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-36-320.jpg)

![1.4 Modeling Considerations 9

is not suitable for these networks but rather the Multi-Protocol Label Switching

(MPLS) will be more advantageous [133, 161, 90, 180, 113]. OPS/OBS networks

using MPLS are also referred to as LOPS/LOBS networks (L stands for labeled).

The idea in LOPS/LOBS is to assign packets/bursts to Forward Equivalent Classes

(FECs). Packets/bursts belonging to the same FEC are forwarded (i.e., routed)

through the same pre-computed path in the network. This reduces the intermedi-

ate routing time at the core nodes to the time it takes to look-up the next hop in

the list of pre-computed routes for the corresponding FEC. Pre-computed routes

are very useful since they can be designed to meet certain quality of service (QoS)

metrics such as delay, hop-count, bit error rate (BER) or bandwidth consumption.

For these reasons, the analytical model in Part III of this thesis is designed for

LOPS/LOBS networks and the existence of FECs is assumed.

The OPS/OBS data and control planes described in Sections 1.2 and 1.3 behave

deterministically. That is, OPS/OBS networks operate in a predictable manner

given full knowledge of their input trac [83, 134]. Taking into account this

deterministic feature represents one of the main achievements of the analytical

model presented in Part III.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-37-320.jpg)

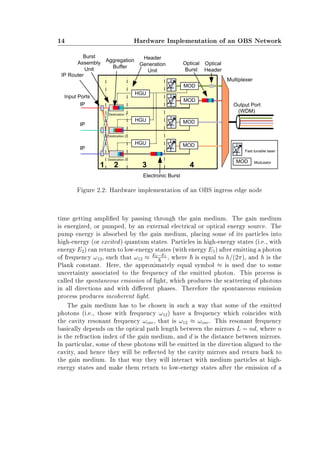

![12 Hardware Implementation of an OBS Network

Figure 2.1: Four elements in an OBS network and associated technological require-

ments. The elements are numbered from (1) through (4), and the technological

requirements are presented in underlined text.

imperfections at these devices produce the accumulation of signal degradation

across the network [116]. This increases in turn the bit error rate (BER), dened

as the average probability of incorrect bit identication at the egress edge nodes [4],

and ultimately limits the size of the network. Thus, the technological requirement

here is to control the amount of signal degradation in our network and to keep

it under a certain limit (e.g., many optical networks allow a maximum BER of

10−9

[12]).

Second, the photonic devices in an OBS network must operate fast enough in

order to be able to process a burst that arrives immediately after another burst

that has left the device. This is a consequence of OBS networks being packet-

switched. More specically, some authors (see for instance [67]) set the operating

time for the photonic devices in an OBS network in the range of µs. This value

will be used throughout this chapter as the operating time requirement for OBS

networks.

There are other technological requirements related to the implementation of

each one of the four elements in an OBS network (ingress edge nodes, transmis-

sion links, core nodes or egress edge nodes). These requirements are presented in

underlined text in Figure 2.1, together with the particular element they are re-

lated to. In particular, the main technological requirement for ingress edge nodes

is to have fast tunable lasers in order to generate the optical bursts. The main re-

quirement for the transmission links is to have gain-stabilized Erbium-doped ber

ampliers (EDFAs) [4, 116] in order to amplify the optical signal. The main tech-

nological requirements for core nodes are three: First, an optical switching fabric

to switch bursts between incoming and outgoing bers. Second, a wavelength con-

version unit (λ-conversion in Figure 2.1) to switch bursts from one wavelength to

another. Third, FDLs to regenerate the oset times between headers and bursts.

These FDLs are not to be confused with the considerably larger FDL lines that a

typical OPS network will use in order to reduce contention at the core nodes [83].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-40-320.jpg)

![2.2 Hardware Implementation of an Ingress Edge Node 13

The main requirement for the egress edge node is to have a burst mode receiver

unit capable of extracting IP packets from incoming optical bursts.

The remainder four sections in this chapter describe the above mentioned tech-

nological requirements associated to the implementation of each one of the four

elements in an OBS network. As it may be noticed, all these requirements are

associated to the manipulation of optical signals, which is nowadays far more di-

cult than the processing of electronic information. Therefore, this chapter mainly

focuses on the optical hardware required to build an OBS network, and addresses

the electronic hardware requirements only supercially [16].

2.2 Hardware Implementation of an Ingress Edge

Node

Figure 2.2 presents the main elements in the hardware implementation of an OBS

ingress edge node. We begin this section by explaining how the hardware imple-

mentation in Figure 2.2 matches the functional description of an ingress edge node

in Section 1.2.

Incoming IP packets are sorted by an IP router and sent to dierent burst

assembly units according to their destination (see 1 in Figure 2.2). Each burst

assembly unit contains an aggregation buer that collects IP packets until an

algorithm called the aggregation strategy decides to stop the aggregation process

(see 2 in Figure 2.2). When this happens, the contents of the aggregation buer

constitute the electronic version of a burst. At this point, the ingress edge node

electronically generates the header packet associated to the burst at the header

generation unit (see 3 in Figure 2.2). The ingress edge node sends the header

packet through the signaling wavelength channel at optical domain, waits a certain

oset time and then sends the contents of the aggregation buer as an optical burst

through the corresponding data wavelength channel (see 4 in Figure 2.2).

The IP routers, burst assembly units and header generation units in Figure 2.2

can be all implemented with digital electronics, and pose no challenge to current

technology. However, the transmission of information through the optical domain

requires the use of two photonic devices: fast tunable lasers and optical modulators

(see Figure 2.2). We now proceed to explain the basic functioning of a laser and

then introduce the state-of-the-art on fast tunable lasers which can be used in

OBS ingress edge nodes. At the end of this section we briey explain the basic

principles of optical modulation formats.

A laser consists in a gain medium inside an optical cavity, with a means to

supply energy to the gain medium. In its simplest form, the optical cavity consists

of two parallel mirrors arranged such that light bounces back and forth, each](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-41-320.jpg)

![2.2 Hardware Implementation of an Ingress Edge Node 15

photon in the same frequency (ωcav), phase, and direction (parallel to the cavity

axis) as the incident photons. This interaction is called the stimulated emission of

light, and gives rise to a coherent beam of light that is characteristic of a laser.

Nevertheless, it could also happen that some of the photons that are being

reected back and forth in the cavity mirrors, are absorbed by particles with

energy E1, instead of producing stimulated emission from particles with energy

E2. Therefore, an important condition in order to produce amplication of the

stimulated emission, is that the number of particles with energy E2 exceeds the

number of particles with energy E1. In that case, population inversion is achieved

and the amount of stimulated emission due to light that passes through is larger

than the amount of absorption. Hence, the light is amplied. Typically, one of

the two cavity mirrors, the output coupler, is partially transparent. Part of the

light that is between the mirrors (i.e., is in the cavity) passes through the partially

transparent mirror and appears as a narrow beam of light with a wavelength

λ = 2πc

ωcav

. This wavelength can be tuned by changing the optical path length

L, either by varying the refractive index n of the cavity medium or the cavity

length d [16]. In this case we have a tunable laser. We now briey describe the

state-of-the-art on tunable lasers which can be used in OBS networks.

The refractive index of the cavity medium can be changed by means of temper-

ature variations or current injection, whereas the cavity length can be changed by

using MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) [10]. Temperature variations

leads to slow tuning devices, which cannot be used for OBS [16]. Fast tunable

lasers based on current injection or MEMS constitute promising candidates for

OBS. The most common current injection-based implementation is the multi-

section Distributed Bragg Reector (DBR) laser. Several working prototypes have

been implemented in the labs recently [146, 13, 137, 93, 6], and all of them have

exhibited tuning times in the range of ns. According to Section 2.1 the required

tuning time for OBS networks is in the range of µs, thus this gure is three orders

of magnitude below the OBS requirement. The most common MEMS-based im-

plementation is the External Cavity Laser (ECL). At least two working prototypes

have been implemented in the labs [11, 97] showing tuning times below 50 ns, also

suitable for OBS. Finally, Intune Technologies [85] commercializes in its AltoNet

series tunable lasers with tuning speeds between 50 and 200 ns. This is the only

example of a commercial tunable laser suitable for OBS that we have found.

OBS networks do not require specic optical modulators dierent from the

ones used in other optical networks. Thus, we now briey introduce the reader

to the basic concepts in optical signal modulation and refer to [4, 116] for de-

tails on this subject. The optical signal generated by a laser is analog in nature

and constitutes what we call the optical carrier signal. A carrier signal may be

thought of as a container to carry information across the network. In our case,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-43-320.jpg)

![2.3 Hardware Implementation of an Egress Edge Node 17

(a) (b)

Figure 2.3: (a) Hardware implementation of an egress edge node. (b) Detailed

implementation of a burst mode receiver for OBS networks using an IM/DD mod-

ulation format.

cic burst-mode receivers. The internal structure of a typical burst mode receiver

is presented in Figure 2.3(b) [152, 145, 119, 48, 158] for the case of an IM/DD

modulation format. At a rst stage the optical burst is converted to the electronic

domain, usually by means of a photodiode. The detailed description of such de-

vices falls out of the scope of this chapter, since they are the same used in a normal

(i.e., non OBS) optical receiver. We refer to [4, 116] for details on this subject. The

output of the opto-electronic converter is an electronic analog signal, which is then

converted to a digital signal by means of an analog to digital converter (ADC) (see

Figure 2.3(b) ). This ADC has two quantization steps, that is, it provides a digital

output of one bit for each sampled value of the input analog signal. Moreover, it

is an adaptive ADC, since the size of the quantization steps is changed according

the to magnitude of the input signal.

In OBS networks a preamble precedes the transmission of each burst. This

preamble is just a sequence of bits containing no information, and it represents

a small fraction of the total burst length. Burst preambles are used by the clock

recovery unit to obtain the signal clock so that the analog signal can be sampled

for the ADC. The typical preamble duration in OBS networks is in the order of

µs (see Section 2.1). The clock recovery unit is needed since OBS networks are in

most cases asynchronous [135, 67]. In a synchronous network this clock recovery

unit is not needed because in this case the modulation and demodulation processes

at the ingress and egress edge nodes are coordinated by a global clock signal.

In an OBS network the optical signals corresponding to dierent bursts might

have traveled along dierent paths experiencing dierent losses and amplications

on their way. This implies that a receiver must be able to dynamically adapt to

such power level variations, which otherwise might severely increase the quantiza-

tion error at the ADC. This is done at the quantization adjustment unit, which](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-45-320.jpg)

![18 Hardware Implementation of an OBS Network

chooses an appropriate size for the quantization steps in the adaptive ADC in

Figure 2.3(b) according to the power level of the incoming burst.

Once the sizes of the quantization steps have been selected and the clock signal

has been recovered, the burst mode receiver can convert the analog signal into a

digital signal of zeroes and ones at the ADC. At the last stage of the burst mode

receiver, the dierent IP packets comprising the burst are extracted and sent to

the IP router for further forwarding through the Internet.

The design of burst mode receivers for other modulation formats is more com-

plex and implies in general the use of more photonic devices operating on the

optical signal before it reaches the opto-electronic converter. The main goal of

such additional devices is to convert the modulation of the optical carrier signal

(e.g. in phase, or polarization) into a modulation in intensity which can be de-

tected by the photodiode (i.e., by the opto-electronic converter) in Figure 2.3(b).

The rest of the elements in the gure are then basically the same.

In the last years several burst mode receivers have been demonstrated for 10

Gbps [145, 119] and for 40 Gbps [48]. In addition, some all-optical burst mode

receivers and clock recovery units have been experimentally demonstrated for 40

Gbps in [92] and [79], respectively.

2.4 Hardware Implementation of a Transmission

Link

The possibility to send great amounts of information through long distances at a

relatively low cost makes optical networks the natural choice to implement core

networks. Optical networks provide such possibility thanks to two main techno-

logical breakthroughs: dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) systems

and EDFAs [4, 116].

DWDM systems multiplex multiple optical carrier signals on a single optical

ber by using dierent carrier wavelengths. That is, one ber is transformed into

multiple virtual bers or wavelength channels which can transfer information in

parallel. Typical wavelength channel capacity values are 1 Gbps, 2.5 Gbps or

10 Gbps (40 Gbps in the near future) [106]. The number of wavelength channels

multiplexed in the same DWDM ber ranges from tens to a few hundred, providing

current DWDM bers with a total capacity in the terabit per second (or 1012

bits

per second) range.

The use of EDFAs allows to compensate the ber losses that take place along

a path for carrier wavelengths in the 1550 nm telecommunication window. All

multiplexed wavelength channels are simultaneously amplied in a single EDFA.

These EDFAs enable the construction of long-distance DWDM optical links at a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-46-320.jpg)

![2.4 Hardware Implementation of a Transmission Link 19

relative low cost.

OBS networks are fully compatible with the DWDM technology [134, 135].

However, commercial EDFAs (or any other kind of doped ber ampliers) cannot

be directly used in OBS networks. Their use would produce large signal power

variations, signicantly increasing the BER [71, 125]. For this reason, we focus

in this section on this problem and study how to modify the basic design of an

EDFA in order to make it suitable for OBS networks, and leave aside the details

concerning the DWDM technology.

This section is structured as follows. First we begin with a description of the

operating principle of an EDFA in Section 2.4.1. We explain in Section 2.4.2 the

reason why a commercial EDFA could not be used in an OBS network. Finally,

in Section 2.4.3 we provide the state-of-the-art of the possible modications to

an EDFA which have been proposed in the literature in order to overcome the

problem mentioned in Section 2.4.2.

2.4.1 The Operating Principle of an EDFA

The operating principle of an EDFA is very similar to that of a laser, explained

in Section 2.2. In an EDFA, a section of the optical ber is doped with the rare

earth element erbium. A pump laser excites the erbium ions into a higher energy

level. Excited erbium ions interact with the photons from the optical signal and

decay back to a lower energy level via the stimulated emission of photons at the

signal wavelength. In the process of stimulated emission the number of photons

in the input signal is incremented and thus the signal is amplied. Together

with stimulated emission, the spontaneous emission of photons takes place in an

EDFA (see Section 2.2). Spontaneously emitted photons in the same direction and

wavelength as the optical signal get also amplied by the EDFA and represent its

main source of noise, the so-called amplied spontaneous emission (ASE).

2.4.2 The Problem of Using EDFAs in an OBS Network

The gain dynamics describe the time scale with which the gain reacts to changes

in the amplitude of the input signal or the pump. In an EDFA such dynamics

are relatively slow, typically in the order of ms [32]. In circuit-switching optical

networks, high bit rate intensity-modulated (IM) light changes its amplitude at a

rate below the ns scale. For instance, a 10 Gbps IM signal changes its amplitude

approximately every 0.1 ns. Thus, in circuit-switching optical networks the gain

of the EDFA is not aected by amplitude variations of the input signal. This

produces a nearly constant amplied output power and we say then that the gain

is stabilized.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-47-320.jpg)

![2.4 Hardware Implementation of a Transmission Link 21

(a) (b)

Figure 2.5: (a) Forward EDFA gain control scheme. The control circuit works

with the power level of the input signal. (b) Feedback EDFA gain control scheme.

The control circuit works with the power level of the output signal.

power of the pump laser is adjusted to countermeasure the variations in the input

signal and the control entity is implemented electronically. In this category there

are two possible congurations. In the forward control conguration [71, 125] (see

Figure 2.5(a)), the control unit receives information concerning the power level

of the input signal. In the feedback control conguration [88, 47, 89, 155] (see

Figure 2.5(b)) it receives information concerning the power level of the output

signal.

In the second category an additional optical signal is introduced in the gain

band of the EDFA in order to countermeasure the variations in the input signal.

Again, the power of the signal introduced can be adjusted by measuring that of

the input signal in a forward (Figure 2.5(a))) or feedback (Figure 2.5(b)) congu-

ration. Additionally, in this case the feedback control scheme can be implemented

all-optically. This is called gain clamping, and has been widely studied in the

literature [30, 110, 181, 177, 100].

In the third category an extra WDM channel is used to compensate the vari-

ation of the total optical power [154, 150, 151]. The power of the extra channel

is adjusted to keep the total power of the extra channel and the signal channels

constant at the input of the EDFA. A promising candidate for this extra channel

in OBS networks would be the signaling channel that carries the header packets.

Because of the low data rates on this channel, it should be possible to design a

receiver which can tolerate the power variations introduced by the compensation

algorithm [16].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3f7f65b2-eeec-4afd-a395-b25a5ff55a20-160530113535/85/Modeling_Future_All_Optical_Networks_without_Buff-49-320.jpg)

![22 Hardware Implementation of an OBS Network

Figure 2.6: Generic OBS core node, courtesy of Siemens AG. HP stands for header

processing, HG for header generation, E/O for Electro-optical conversion, O/E for

opto-electronic conversion, and λ-conversion for wavelength conversion.

2.5 Hardware Implementation of a Core Node

In this section we present the main technological requirements needed in order

to implement an OBS core node, together with state-of-the-art solutions to meet

such requirements.

The main functionality of a core node is to switch and forward the optical

bursts as fast as possible and without causing large burst losses due to contention.

Since contention is one of the main concerns in OBS networks, the purpose of many

of the hardware elements in a core node is to reduce it. In general an OBS core

node comprises six main elements: an input interface, ber delay lines (FDLs), an

optical switch fabric, a wavelength converter unit, a control unit and an output

interface (see Figure 2.6) [134, 135].

At the input interface the wavelength channels are demultiplexed from the

WDM ber. The contents of the control channels are converted to the electronic

domain in order for the burst headers to be processed. After processing, the head-

ers are regenerated and converted back to the optical domain. The data channels

are fed into FDLs in order to regenerate the constant oset time existing between

each header packet and its associated burst (see Section 2.5.1). Then bursts are