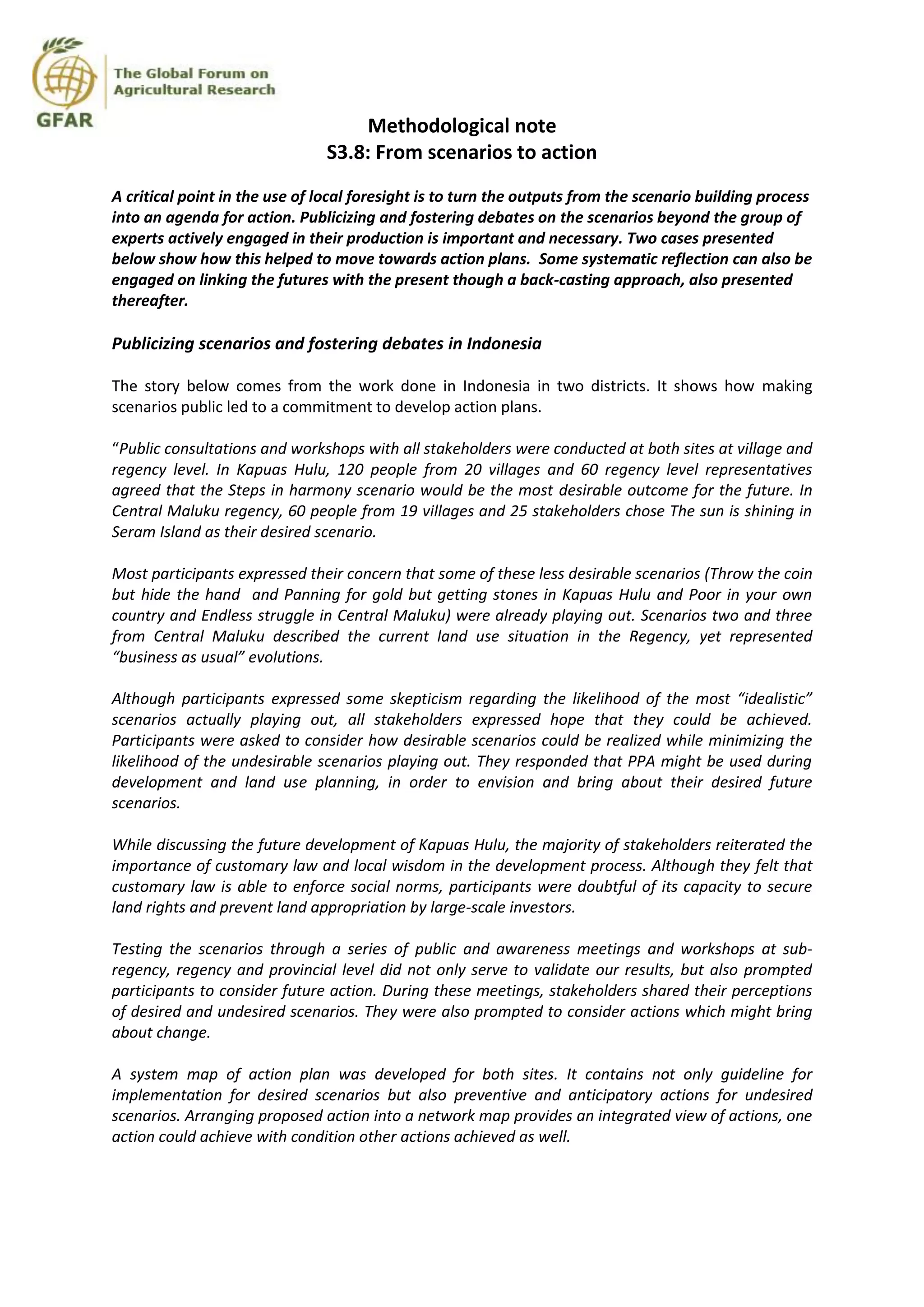

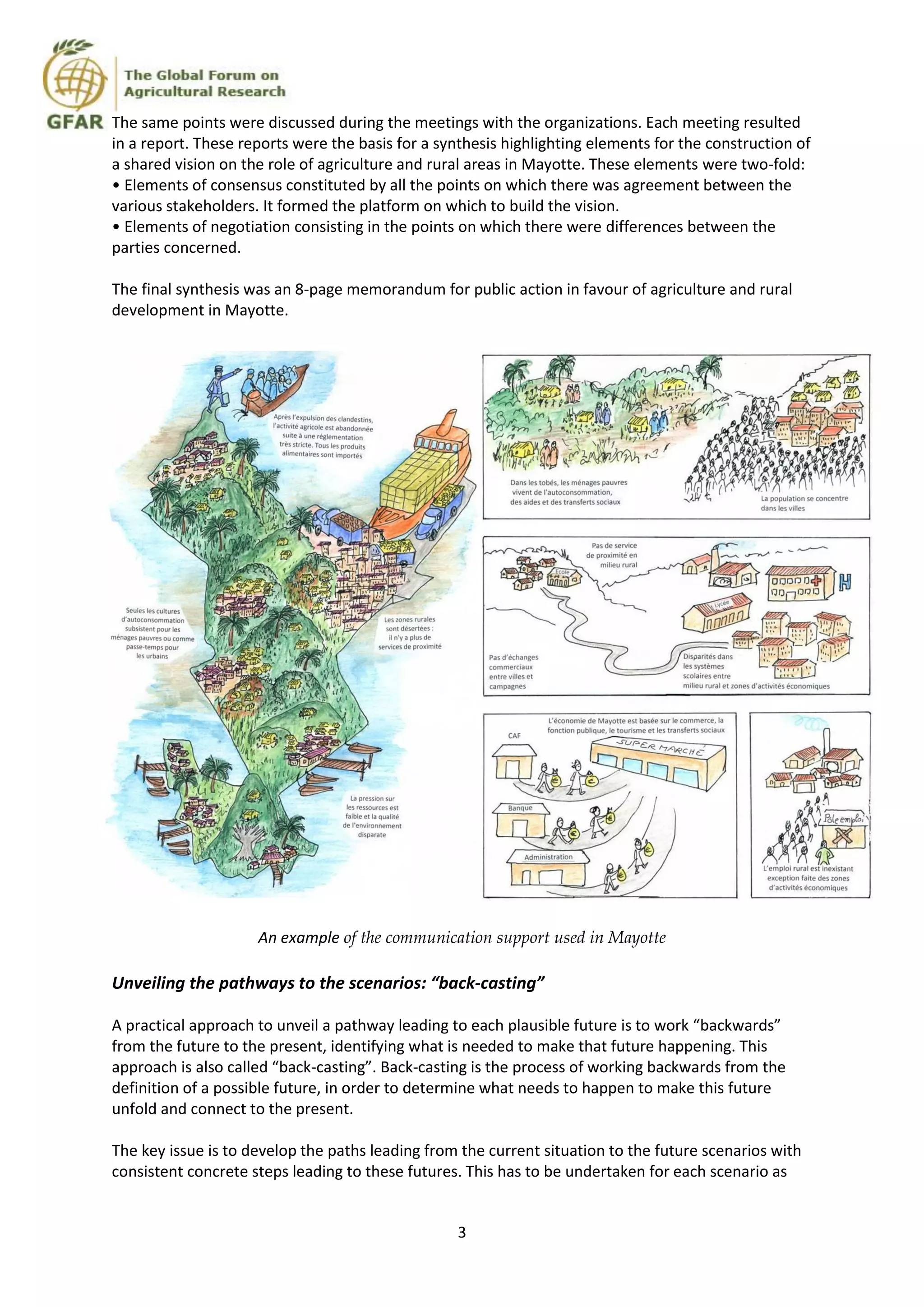

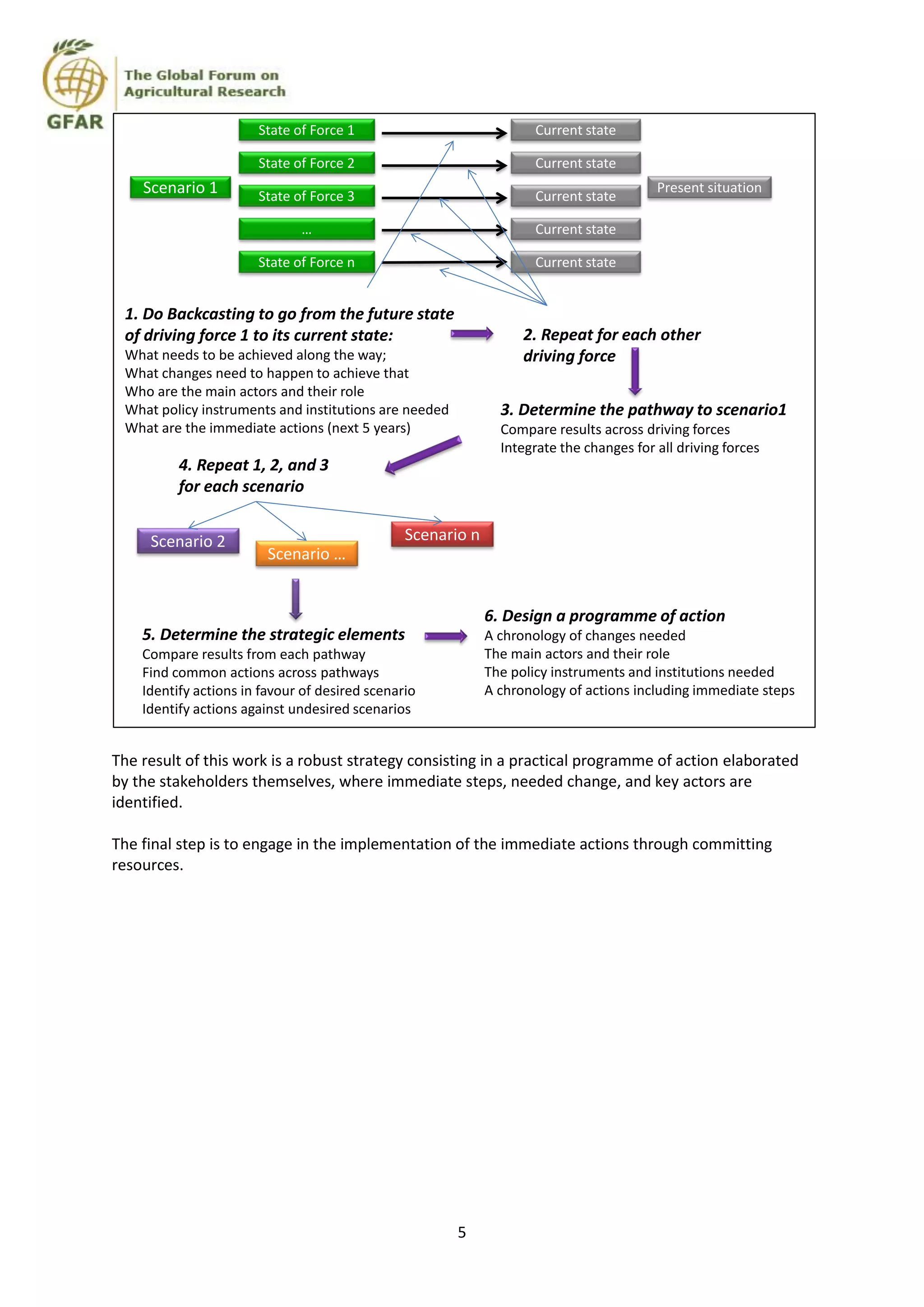

The document outlines the process of transforming scenario outputs from local foresight activities into actionable plans through public engagement and back-casting. It details case studies from Indonesia and Mayotte, demonstrating how public consultations and stakeholder discussions fostered commitment towards desired future scenarios while addressing concerns about less desirable outcomes. The methodology aims to create a robust strategy for implementation by identifying necessary actions, key actors, and institutional frameworks to facilitate desired change.