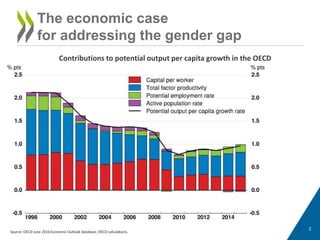

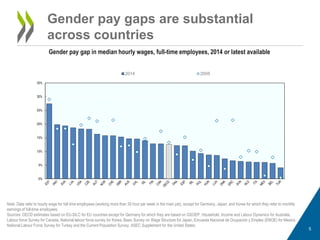

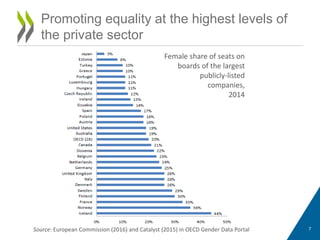

The document discusses measuring and addressing the gender gap across OECD countries. It provides data showing gender gaps in areas like education choices, labor force participation rates, pay, and leadership positions. It summarizes the OECD's 2013 recommendation to promote gender equality in these areas and its 2015 recommendation on gender equality in public life. It also discusses the OECD's work measuring progress, promoting women's empowerment in international forums like the G20 and G7, and efforts to end violence against women.