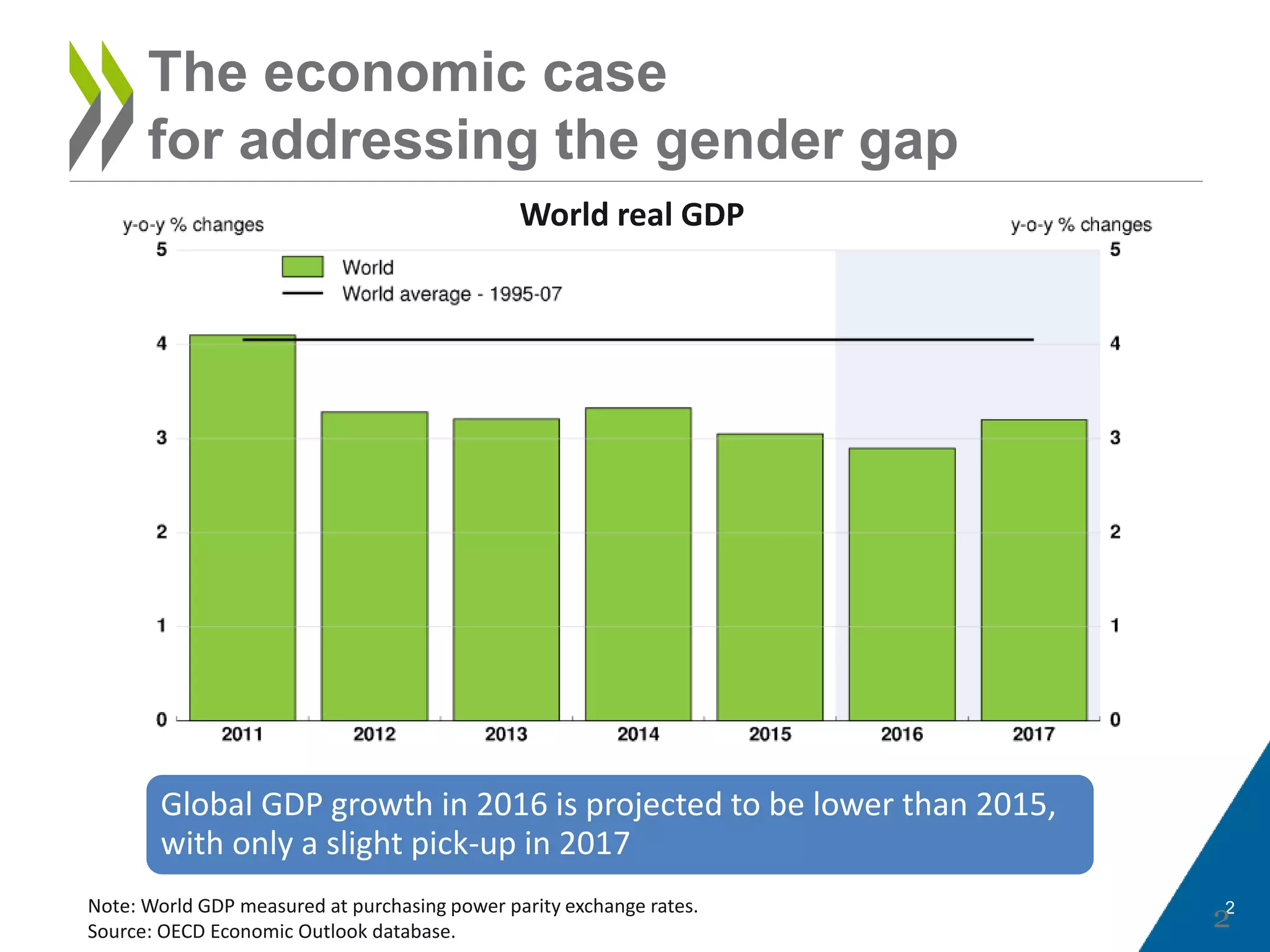

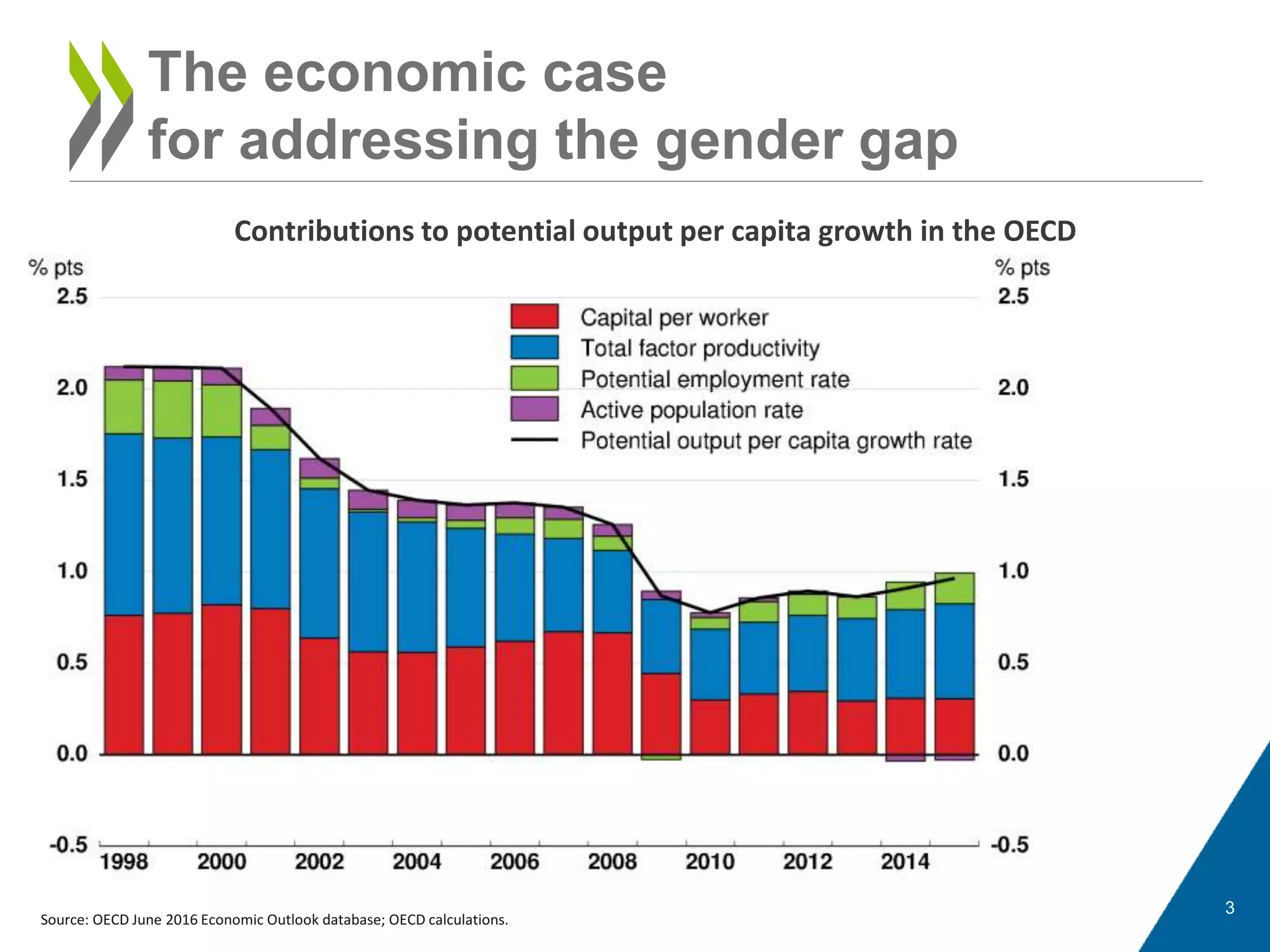

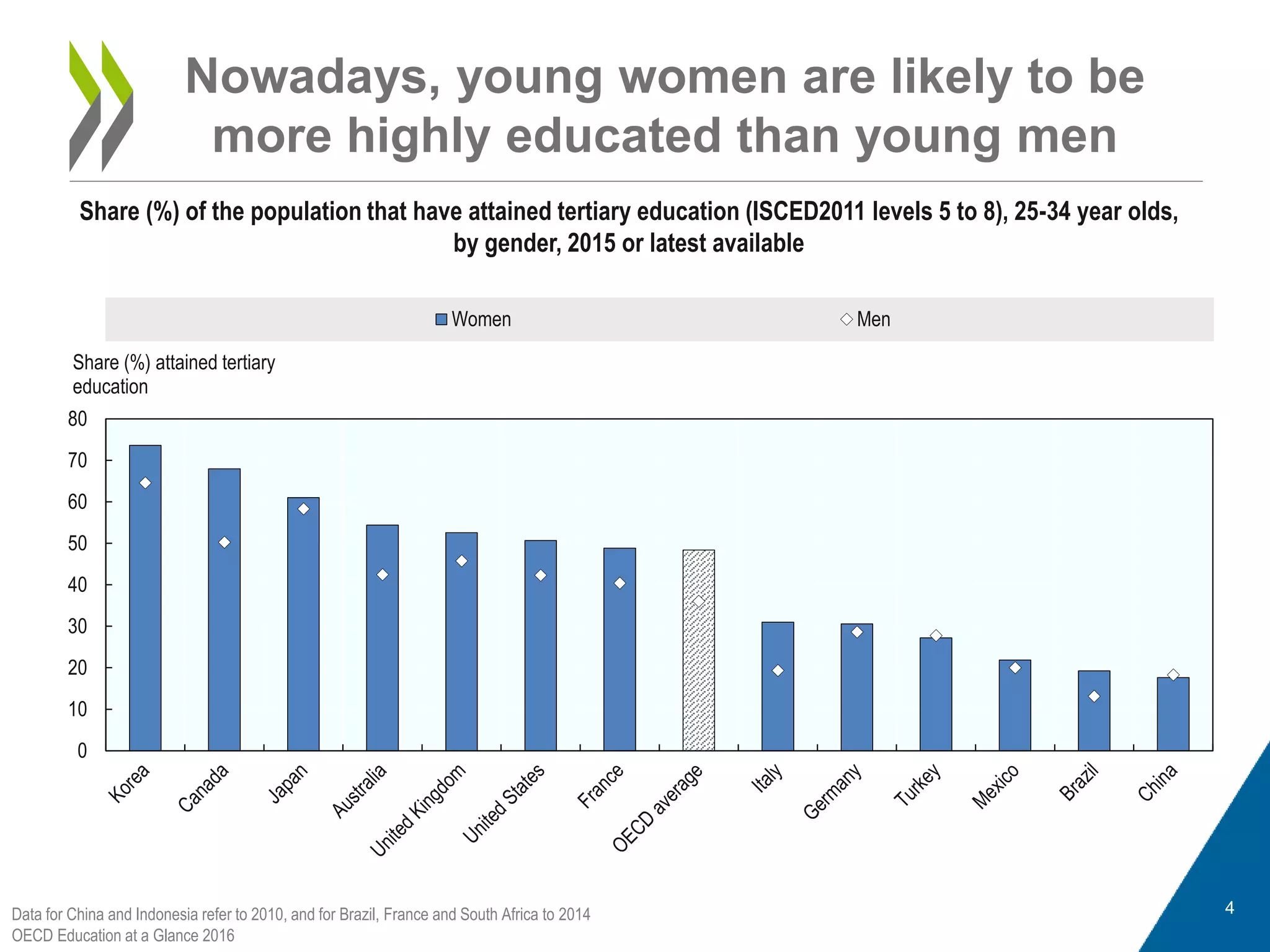

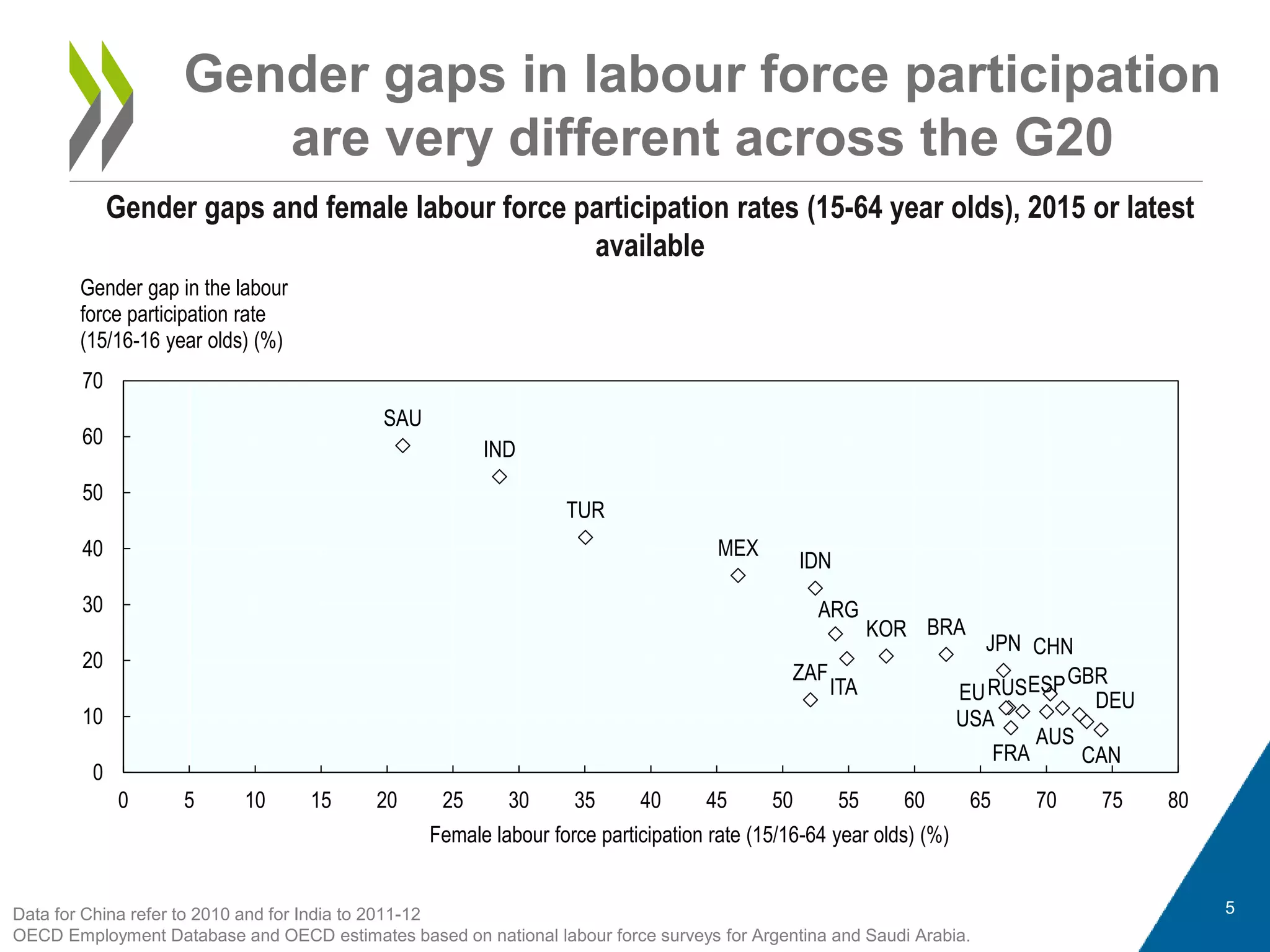

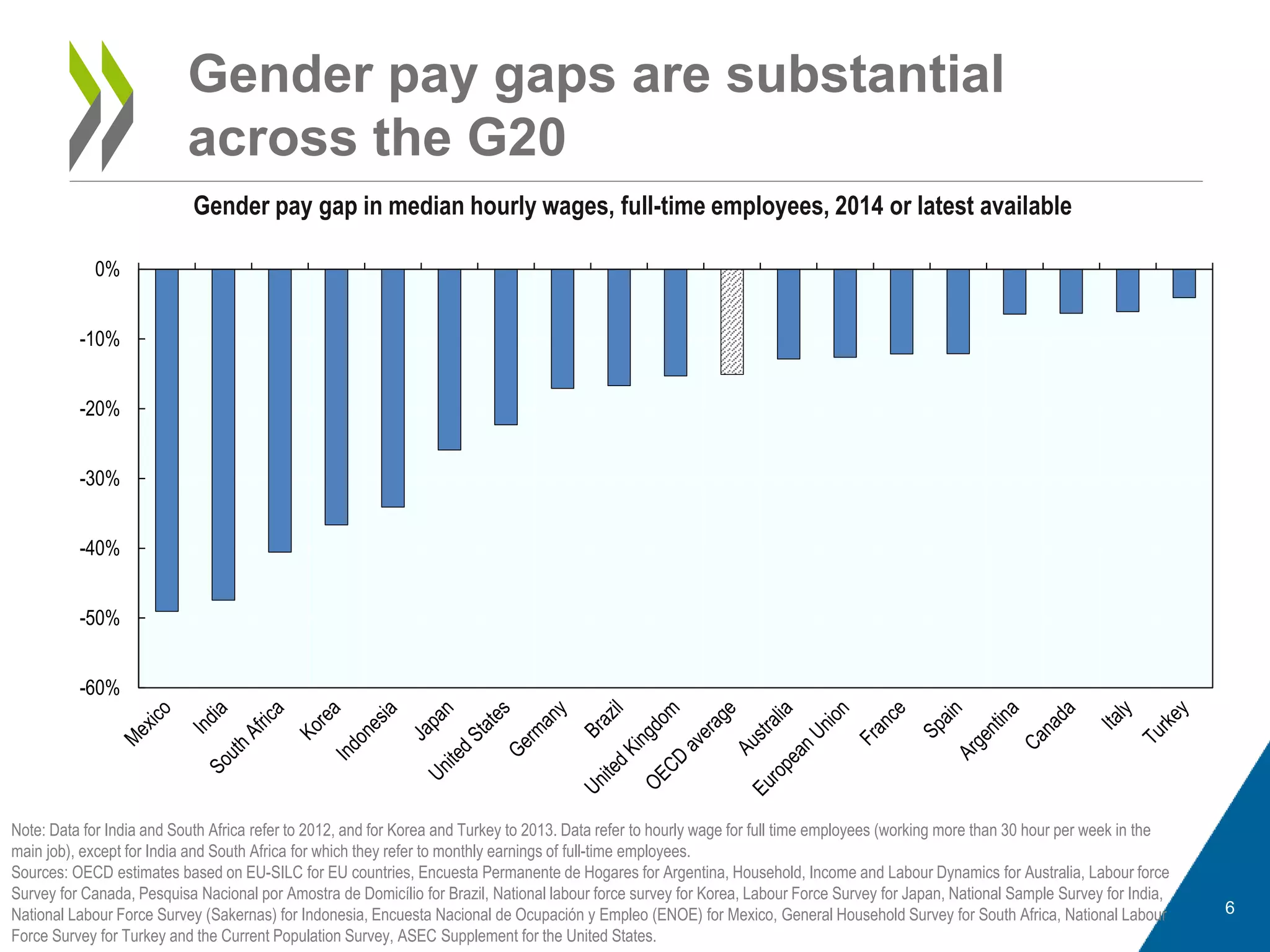

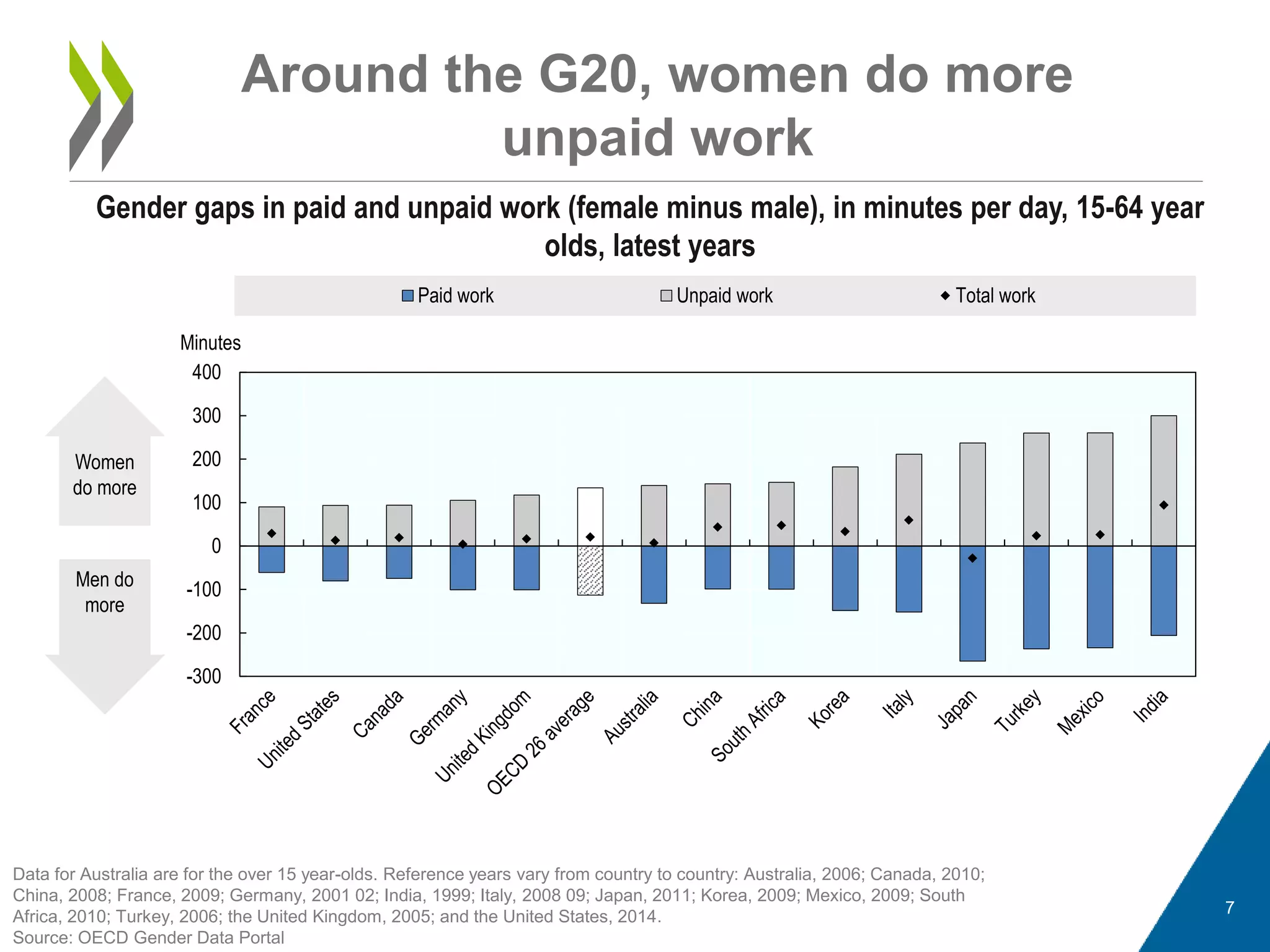

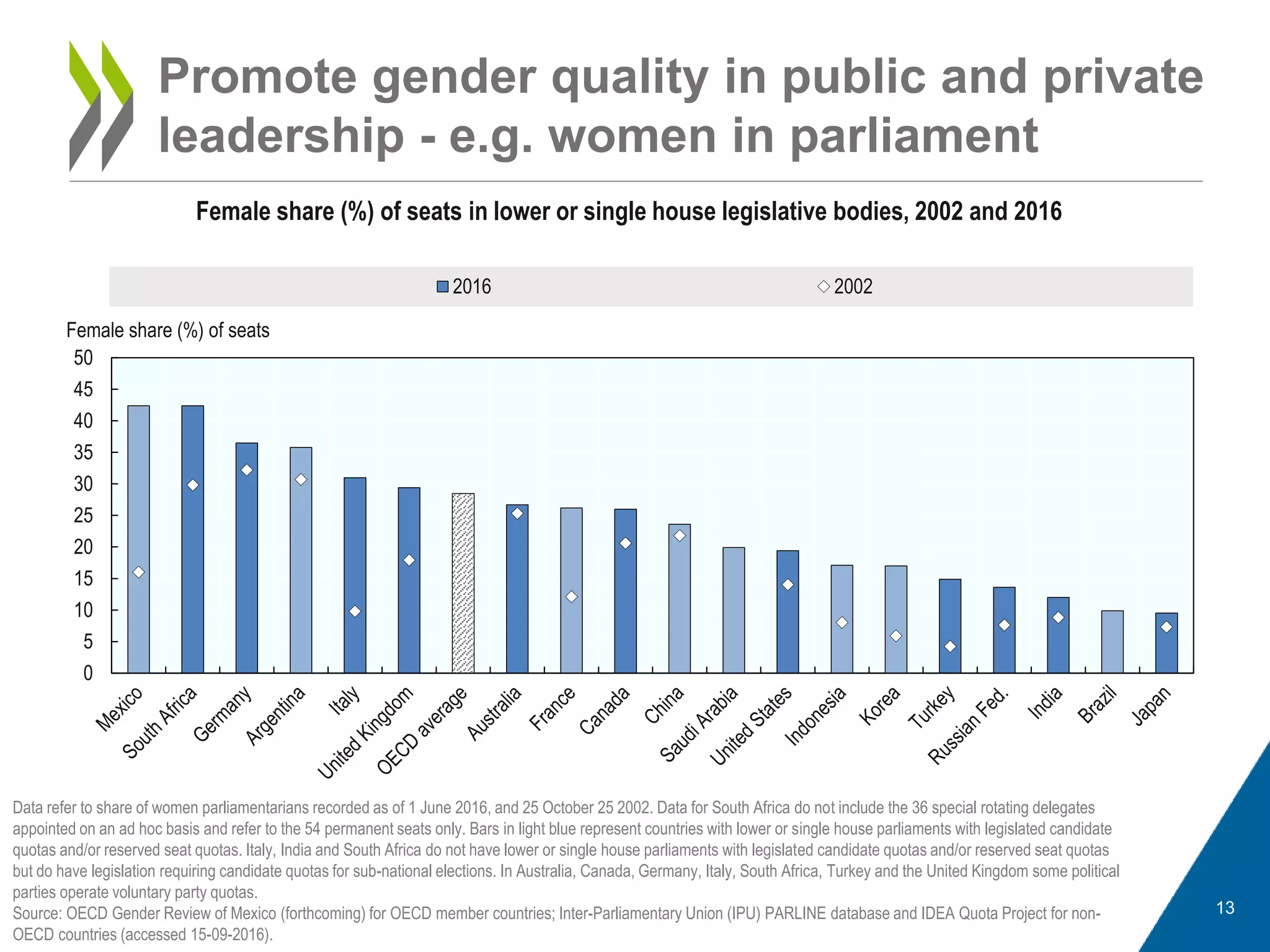

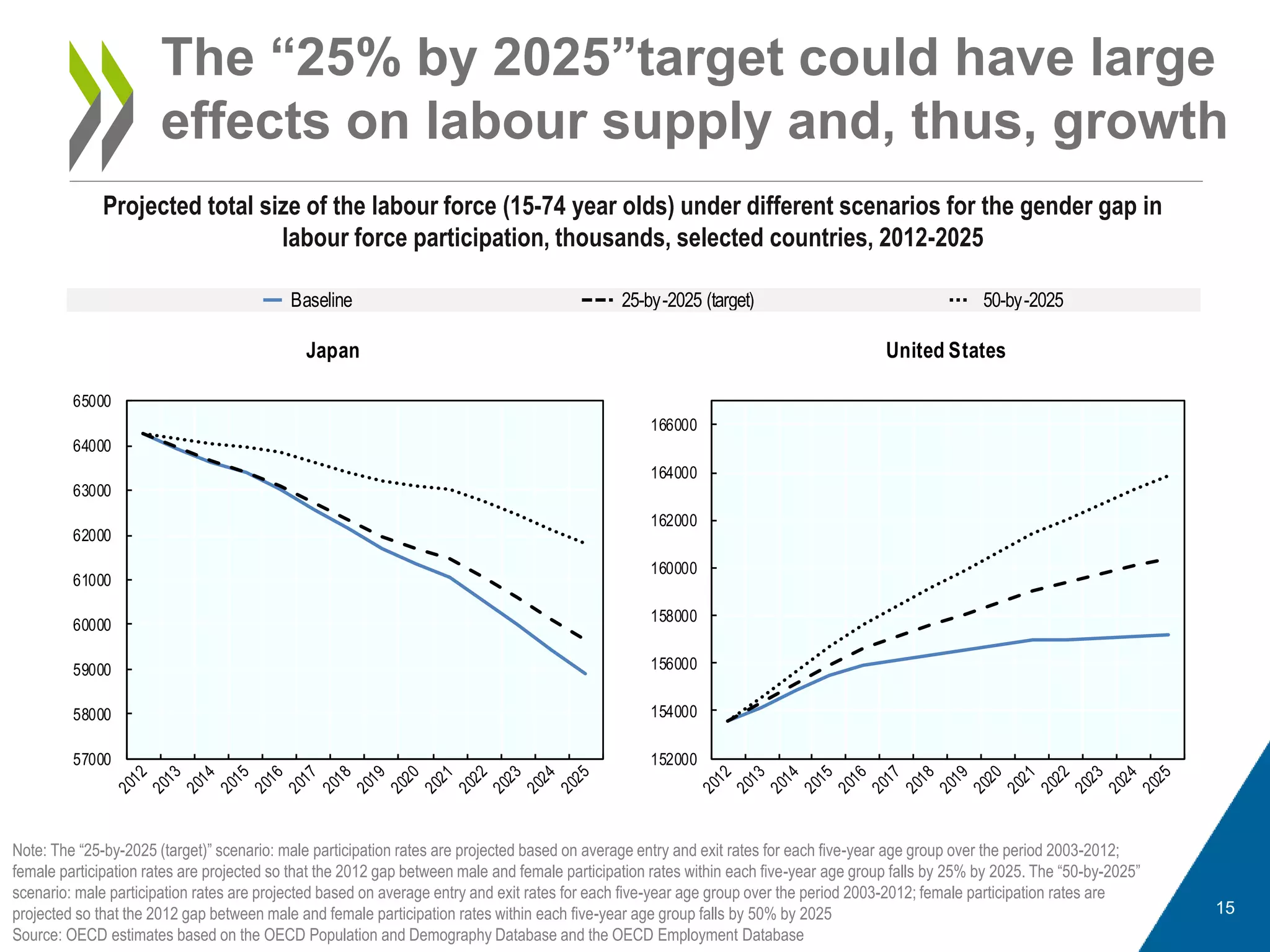

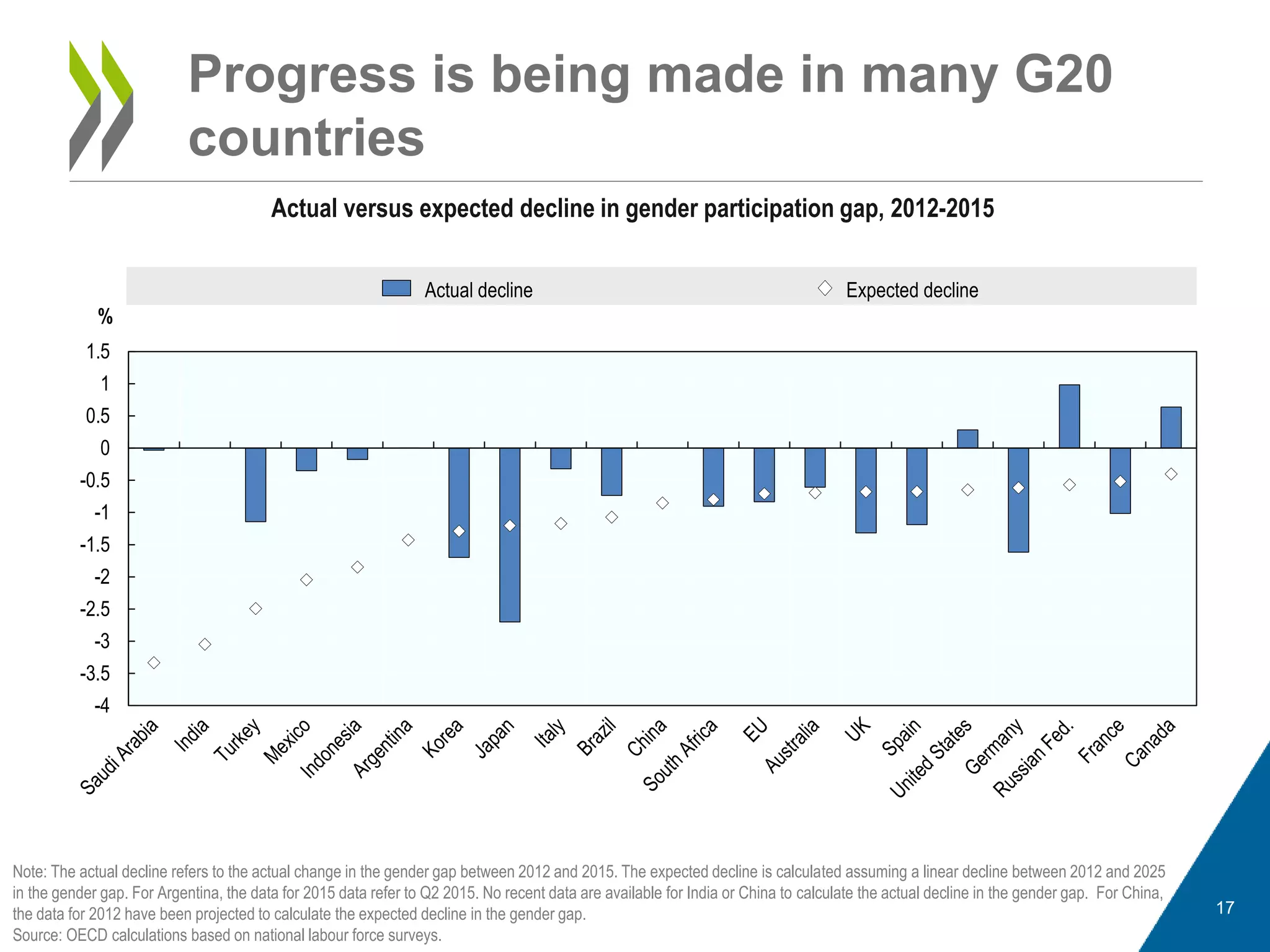

The document discusses gender targets set by the G20 to reduce the gender gap in labor force participation rates by 25% by 2025. It provides background on analysis by the OECD showing the economic benefits of addressing gender gaps. Considerable progress has already been made in many G20 countries towards meeting the target ahead of schedule. The OECD will continue monitoring progress on the target and promoting gender equality policies through its work.